Rise of the Videogame Zinesters is a manifesto that attempts to broach some important problems of representation in the video game industry.1 On her site, Anna Anthropy explains that her book “shift[s] the balance of our dialogues about videogames a little. when our culture discusses videogames, it mentions corporations, blockbusters, and a hyper-masculinized “gaming” culture. Rarely does the idea of the small, authored, self-published game get much air in our discussion of art.”2 Because our culture treats ‘game’ as a synonym for ‘videogame,’ we can understand why Anthropy frames her argument in these terms. Ignoring the broader world of games is folly, as a zinester3 attitude prevails in board game cultures as well. Board games share many of the virtues held by the micro-videogames to which Anthropy refers, like strong authorship, small scope, and often self-publishing as well. This essay considers the ways in which micro-publishing models have allowed boardgames the leeway to tackle critical themes that the major publishing industries preclude.

Board game designers have less visibility than video game designers because it is much harder to distribute a board game than a video game. Since a video game’s distribution costs can be close to zero, designers can afford to post their games on the Internet where anyone can play. Because these avenues of funding are not available to board game designers, it can be difficult for authors to express their message without incurring significant costs. Some niche board game designers have proposed a variety of strategies to ameliorate this problem.

UK company Hide & Seek has published several iOS apps, books, and cards that provide new rulesets for old boardgames. The Board Game Remix Kit4is a book that tells players how to mix and match pieces from Clue, Scrabble, Monopoly, and Trivial Pursuit in order to create both variants and entirely new games. Hide & Seek followed their book with Tiny Games, an app that gives players rules for hundreds of miniature games that help to critique everyday situations. For example, while watching TV, you might play I Told You So, where one person guesses what the next ad will be about, the television is muted, and then that player has to argue that the ad shown matches their description, regardless of the actual content. By turning players into active participants, the game sets up a situation that makes it easier to see the similarities between ads and the absurdity of the situations they depict.

Another way of combating initial costs is to include the game with another purchase. Often, board game rules are included as part of conference programs or magazines. Brian Train’s Battle of Seattle (2000) is a small game with a traditional, although simplified, wargaming structure that engages the 1999 Seattle anti-World Trade Organization protests. In this game, one player takes the part of the protestors and attempts to control locations while minimizing looting while the other player acts as a collection of civil authorities and tries to shut down protests without being exposed by the media. Since Battle of Seattle was included freely in Strategist magazine, it reached a much broader audience than Train could have reached on his own and encouraged readers to consider the anti-WTO protests as a wargame with two asymmetrical forces.

More recently, morac released A Night in Ferguson (2014), a solitaire game played with a normal deck of cards that is based on the protests staged after the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO. The game is available as a pay-what-you-want PDF download and is played by creating stacks of cards where black cards represent protestors and red cards represent police. The police automatically arrest the black cards in their location. The game’s goal is to finish the deck, thus ending the night and helping the protesters to avoid arrest. It is unlikely that a mainstream publisher would support such an overtly political message, and so because of this and the games simple and easily shared components, the game is fundamentally resists commercial appropriation.

Another strategy of accessibility that board game designers have experimented with is running their games at events. Here, players can play for free while the designers pay only to produce the copy of the game used for play. This model helps designers test new ideas which may be too radical for the mass market, while admittedly forfeiting the mass distribution networks that Anthropy exalts in her book. Naomi Clark’s Consentacle (2014) offers a strong example of this radical design practice. In this two-player card game, a human and a tentacled alien try to have sex without being able to communicate. Each player secretly selects a card and when revealed, the cards take effect: trust is swapped, stolen, and/or converted into satisfaction. Consentacle deals with issues of trust in relationships by abstracting the concept into a resource to be exchanged from player to player.

Brenda Romero has advanced this concept by framing her games as installation pieces that can be played with without the designer’s influence in her The Mechanic is the Message (2008-present) series. The series is best known for Train where players are tasked with packing yellow people figures into miniature train cars and running them across tracks balanced on broken windows laid flat. As the game progresses, Romero asks “Will people blindly follow rules?” and “Will people stand by and watch?” At some point during the game, players realize that they have unwittingly taken on the role of Nazi soldiers sending prisoners to Auschwitz. Romero allows people to draw their own conclusions, with some continuing to play the game and others refusing to be a party to it. In any case, players now have a more visceral understanding of how context affects the interpretation of games.

Board game designers face many of the same difficulties as videogame designers. For instance, there is a problematic lack of diversity in both game design communities and this perhaps offers a clue as to why so many games are themed around war and conquest. Boardgames also tend to exoticize and ‘other’ the subjects of their games, whether they are Wall Street traders in Edgar Cayce’s Pit (1904) or a market in Rüdiger Dorn’s Istanbul (2014). Boardgames that approach problematic themes often remove the questionable areas entirely as they abstract the mechanics rather than deal with them directly. For example, in Klaus Teuber’s Settlers of Catan (1995) native inhabitants are conspicuously absent on the island, there is a mysterious robber pawn that can be said to represent the native tribes. The pawn however, is controlled by the players and represents natives only in so far as they are instrumental to player goals.

Even when mainstream boardgames do work to reveal dense political and economic systems through their design, they can be limited by a sense of what their audience is willing to accept. For example, Christophe Boelinger’s Archipelago (2012), features a set of “natives” which are press-ganged into work by players and then must be pacified with churches lest they rebel. However, all of the processes involving the natives are abstract and it is hard to read a deeper cultural message than “there were natives before colonists arrived.” Liam Burke’s RPG Dog Eat Dog (2012) has a very similar theme but was self-published using Kickstarter as a platform, which gave the designer much more leeway. This game casts most players as Natives who must contend with the arbitrary rules set by the player acting as an outside Occupation force. The game ends with all Native players assimilating to the Occupation to some extent or running amok and entirely rejecting the Occupation. New tools and strategies like these allow game designers to bypass mainstream publishing and address social issues more honestly and openly.

Unfortunately, many amazing games never reach a wide audience because of hard limits in production and distribution costs. This paper outlined some of the innovative strategies being used to challenge this seemingly impossible obstacle. As crowdfunding reduces costs for designers and niche publishers alike, print-on-demand5 publishing has also become a reasonable option for many games that use common pieces. These print-on-demand services have also begun setting up digital storefronts, making it easier to for designers to distribute quickly and efficiently as well.

Many full games and re-themes have become available as print-and-play6 versions. The fan-moderated website, Board Game Geek, has a vibrant print-and-play culture, which offers many cheap games for both designers and players to download. There is a catch, however, as players must endeavor to craft these games, assembling them themselves. Some games though, like A Night in Ferguson, use common components so that the print-and-play version consists of just the rules. This method of distribution offers the best of all worlds as the player’s work is minimized.

Boardgames have long provided an avenue to tackle important social issues in an engaging and striking way. However, the costs to print and distribute these games have made it difficult to reach a significant audience without a publisher. These publishers outright reject or elide messages that don’t align with their goals, primarily a mass-market appeal they can sell at a minimum cost to themselves. Clever designers have found ways to bypass this system, by piggybacking on other distribution systems like magazines or by self-publishing at significant expense. New opportunities make it increasingly viable for designers to create and distribute small, personal games that accurately represent their viewpoints and for players to discover games that speak to them directly. A variety of welcoming game conferences like No Quarter and IndieCade allow designers to directly engage with players, while web forums, blogs, and online databases have reduced distribution costs drastically, particularly for games that repurpose existing game pieces. For designers who are able to promote themselves effectively, crowdfunding sites provide a way to remove middlemen and to raise the funds necessary for a quality print run. With these recent changes, even more designers have begun to create important games that wouldn’t be possible with mainstream publishing’s conservative business model.

–

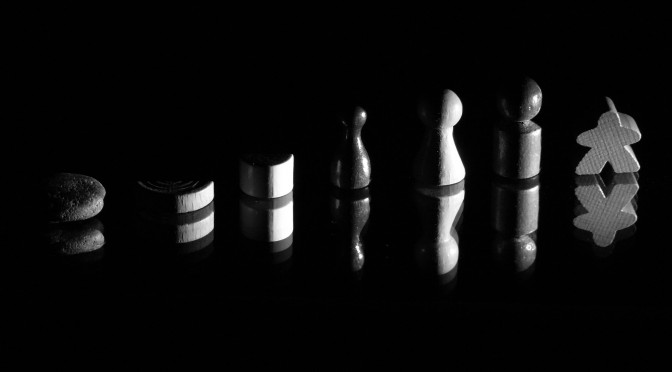

Featured Image by ktina83 @Board Game Geek.

–

Will Emigh is a Lecturer in game design at the IU Bloomington Media School in addition to being a video and boardgame designer at his company, Studio Cypher. His physical work includes Tattletale!, a card game based on the Prisoner’s Dilemma published in 2014, and Stickers in Public, a set of games on stickers that can be placed anywhere. Highlights of his digital work are The Cyphers, a series of short alternate reality games released in 2007, and four kiosk games for the Chicago Field Museum’s Ancient Americas Exhibit. He is currently working with partners to use motion-tracking technology to make physical therapy more effective and bearable for stroke victims and children.

In addition to his day jobs, Will is on the board of the Humanetrix Foundation and organizes Sigma Play, a hands-on conference for games designers of all types, and Bloomington Indie Game Nights, a monthly gathering of hobbyist game designers in Bloomington, IN.

He can be reached at wemigh [at] indiana.edu.

Thanks for an interesting exploration of the issue, Will.

About Battle of Seattle: I should point out that Strategist magazine, at the time, had a circulation of 100 copies!

During the year that I edited that zine, I also ran small games on arms dealing, trench warfare, the Zulu War, submarine warfare, and the Battle of Waterloo (using only 18 counters).

It ceased production shortly thereafter.

I put the game up for free print and play on my website, along with a few others (http://www.islandnet.com/~ltmurnau/text/gamescen.htm) , and eventually it was “copylefted” onto some left-wing and anarchist websites.

I don’t mind.

For many years I have designed boardgames that are primarily about conflict, but which have a heavy mixture of politics or stress the asymmetry between sides – I have covered some of the nastier kinds of insurgency, in games that are owned by only a few people (hundreds in some cases, dozens in others).

I have found that wargamers are generally highly intelligent people, but sometimes the use of that intelligence is limited to a narrowly defined range of interests.

For many of them the game, and winning, is the thing, and whatever conflict the game is supposed to simulate is of secondary importance – a game is a puzzle to be cracked, and rules are to bend until they break.

For others, the topic is the thing – and they demand ultimate historical versimilitude in “monster games” with thousands of counters – I find it amusing that these kinds of games that deal with the Eastern Front of WW2 are graded for the accuracy of their order of battle, including the regiments and brigades of the Sicherheitsdienst and various SS national contingents – units whose historical function was murder and ethnic cleansing, but who have nothing to do in the game because what designer would write “realistic” rules for that?

But in the main, I find many wargamers to be simply conservative.

They like what they like, and they are difficult to move from that entrenchment.

Likewise, they don’t like what they don’t like – and in large part that includes politics, uncertainty, moral ambiguity, and many other aspects of “real” war and conflict.

Keep up the good work,

Brian

Thanks for the further background, Brian! Unfortunately, I think many game players outside of the wargaming sphere also tend to be very conservative, particularly in terms of how they evaluate games.

Still, as the market for games expands, I think we’re starting to see more and more really interesting experiments. Hopefully, they’ll start to gain traction and we’ll see a new, more political, niche that’s large enough to support designers.

Thanks Will.

I guess in the end it’s all a snap appraisal – “I don’t know about Art, but I know what I like” does it for most people.

There are a lot of very interesting cross-pollinations going on in game design now.

Techniques and methods are proliferating; all too often it seems that games are designed for the mechanics first and then the theme gets slapped on, to the point where reviewers are starting to describe games in shorthand – in terms of genres and references, the way hipsters review music albums: “It’s like if Puerto Rico and Clue had a baby but kept it in Klaus Teuber’s basement and brought it out only at night to feed on trick-taking”. And so on.