On March 1, 2020, John Lewis, a United States congressman and Civil Rights hero encouraged a crowd in Selma, Alabama to “speak up, speak out, get in the way. Get in good trouble, necessary trouble…”1 Getting in “good trouble” means interrogating and questioning the status quo to achieve necessary changes. We draw on Lewis’s “get in good trouble” to interrogate the name “mancala,” which is a generic term often employed in scholarship and literature to refer to classic African board games.2

Our interrogation of the generic term “mancala,” here employed to discuss classic African board games in board game studies, is informed by a decolonial perspective on knowledge and knowledge building. Contemporary scholars acknowledge the historical interconnection of colonization with research.3 Decolonization is a process that results in the intellectual, psychological, and physical liberation of the colonized from the colonial system impose on them.4 Adopting a decolonial perspective in research allows the dismantling of contemporary knowledge and the recreation of new knowledge; helps rethink how knowledge is gathered, produced, and shared.5 For us, decolonizing research also means taking apart the current story, giving voice to people and things that are often unknown.6 Indeed, the impacts of colonization are physical, psychological, mental, as well as spiritual, because the greatest weapon of imperialism is the “cultural bomb.”7 A cultural bomb is the annihilation of a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities and ultimately in themselves.8 Hence, decolonization means freeing the mind, body, language, culture, praxis, thoughts, theory, research, and ceremonies from Western ideas, philosophies, beliefs, and theories dependency.9 A decolonial approach allows us as members of communities that play these classic African board games to deconstruct the generic term “mancala,” as we challenge its use in board game studies as a blanket term for classic African board games. The use of “mancala” as a generic name is, in our view, the colonization of these African board games through the annihilation of the communities’ given names. Moreover, the encapsulation of classic African board games into the term “mancala” results in the colonization of classic African board game research by Western board game studies.

As previously mentioned, colonization touches many aspects of names and language. Inherent to decolonization or a decolonial perspective is also the need to address the harm of cultural genocide and linguicide.10 As members of communities that have been playing some of these classic African board games for centuries, we discuss, in the next section, a) the importance of naming in relation to African culture; b) examine the meaning of “mancala”; and c) explore the literature to explain how this generic term in board game literature participate in a colonial project that intends to annihilate the names, heritage, history, and language of colonized people. In other words, we are getting into good trouble with analog game studies by demonstrating that “mancala” erases the culture, identity, history, creativity, agency, and language of various communities in Africa.

Names Matter

Naming is critical when one wants to meaningfully address a situation, problem, or phenomenon. Indeed, names are “given to entities of cultural importance and of significance for humans in social life; name usage and name-giving practices reflect social beliefs and cultural values; and their meaning is strongly shaped by cultural and historical contexts.”11 Names can influence the individual or phenomenon under investigation, while reflecting the history, rationale, or biases of the researcher labeling the phenomenon.12 Therefore, names can be misleading or superficial, which may result in framing a situation or object differently or in telling a different story. Names do not just describe a phenomenon; they also reflect the rationale that leads to name creation. As Oyèrónké Oyěwùmí, and Hewan Girma explain, “Names are consequential labels with strong affective meaning that can fulfil multiple purposes as anchors of identity, symbols for the self and markers of ethnicity.”13

Naming a phenomenon captures assumptions, feelings, beliefs, and even history about the said phenomenon or object; thus, misnaming or changing an object’s name inherently undermines or misrepresents any situation or object under study. Addressing naming and naming practices in Africa, Oyèrónké Oyěwùmí argues:

names constitute valuable sources of historical and ethnographic information and help to unveil endogenous forms of knowledge… Apart from documenting historical experiences, … names help to unveil endogenous forms of knowledge… names and naming practices [in]… different African cultures … reveal the historical and epistemic significance of given names.14

In other words, naming makes evident the inferences and characteristics about the object or event labeled; it gives it a general meaning, and shapes how to approach the object, or event, and informs assumptions about the event or object under investigation. Understanding that naming has consequences on how we understand and conceive a phenomenon, our paper focuses on the generic label “mancala” often used in the literature to refer to a family or group of traditional African board games, referred in this article as classic African board games.15

Mancala and Its Meaning

Mancala is a term borrowed from the Arabic “manqala “or “minqala” (from the verb naqala, “to move”), which has been applied to a “set of games involving the distribution of a series of stones or seeds among a number of holes arranged in two, three or four rows.”16 Informed by a decolonial approach, we contend that the danger of using the generic name mancala to refer to all these board games erases the culture, identity, creativity, history, and design history of the various communities/ethnic groups where these games are played and were developed.17 For instance, some authors state that mancala is a game with various forms found in Africa and Asia; mancala has common elements across its variations on the African continent such as always played by two people on boards with rows of holes—the most popular being two rows with six holes and two large holes at each end.18 While recognizing that neighboring countries have different names such as Oware in Ghana, Gabata in Ethiopia, Sora in East Africa, and Ayo in Nigeria, Anthula Natsoulas still explains and assumes that elements of the game mancala are universal, even with special rules, the format remains similar for all games.19 Other researchers define mancala as games made of rows of holes and often played with seeds or shells. The name “mancala” appears to have been attributed to any game that can be described as played on a board with holes, seeds, or shells.20 The use of “mancala” as a generic label for these classic African board games in scholarship and literature could be explained by the fact that African thoughts and realities are often conceived acceptable only when they fit or are defined within or in relation to other paradigms.21 We argue that the desire to categorize all classic African board games played with seeds and on boards with holes under “mancala” is an attempt to apply Western ways of classification. In other words, labeling all these games “mancala” aligns with a) Western language practices of grouping what is deemed similar and b) expectations that Africans should translate these “universal” concepts into their own languages or simply accept foreign concepts or labels.22

In the next section, we examine the usage of “mancala” in recent years. We are interested in knowing whether researchers discussing classic African board games have only employed the name as known by the communities that play these games in their research or have they preferred to use mancala or a combination of mancala and game name from these communities.

Trends in the Use of the Term “Mancala” in Analog Game Studies

To examine the use of “mancala” as a generic name for classic African board games in recent years, we first explore the popularity of the word “mancala” in the board game studies literature, using a combination of a) Google Books Ngram Viewer, which is a text analysis tool that analyzes how words and phrases have been used over time by searching through a large collection of books, documents, and other textual sources scanned by Google from 1500-2022; and b) JSTOR’s Data for Research (DfR), a service that offers text mining of content from multiple platforms, and allows users to analyze word frequencies and trends within academic publications from 1900-2024.23 DfR allows researchers to conduct text analysis focusing on journal articles, while Ngram enabled us to mine text mainly in books and documents. The combination of these text analysis tools provided us with a general overview of the history of the use of the term “mancala” in books and journal articles and helped us have a sense of the popularity of this term at different timespan. Textual analysis is an analysis method that enables a close encounter with the text and is used to examine messages with the goal of understanding sense making practices of people.24 Using Ngram, we were also able to understand what terms were mostly used alongside the term “mancala.”

In the context of this study, Ngram and DfR provide a historical understanding of the use of mancala. In addition to using Ngram and DfR datasets to examine the history of the use of mancala and its popularity in literature, we consider research published in the past five years. Search terms such as “mancala,” “African board games,” and “mancala board games” were employed in the authors’ libraries Quick Search tool and in Google Scholar for the past five years. We were only interested in peer-reviewed articles and not in books or reports. While our search yielded 35 articles with “mancala” or African board games in their titles or abstracts, we discussed selected excerpts. Indeed, using Voyant, which is an open-source, web-based application, we performed a textual analysis of these articles. Textual analysis allows for the examination of a phenomenon or concept as a window into pieces of subculture that may have not been previously studied.25

Overview of Mancala Use

Given our interest in understanding the use of “mancala” as a generic term to refer to classic African board games in the most recent literature, it was important for us to show the historical trend of its usage (Ngram and DfR) but also to take a closer look at the most recent literature to understand whether the term was used in combination with other words, such as the game name known by the communities that play the game or where used interchangeably.

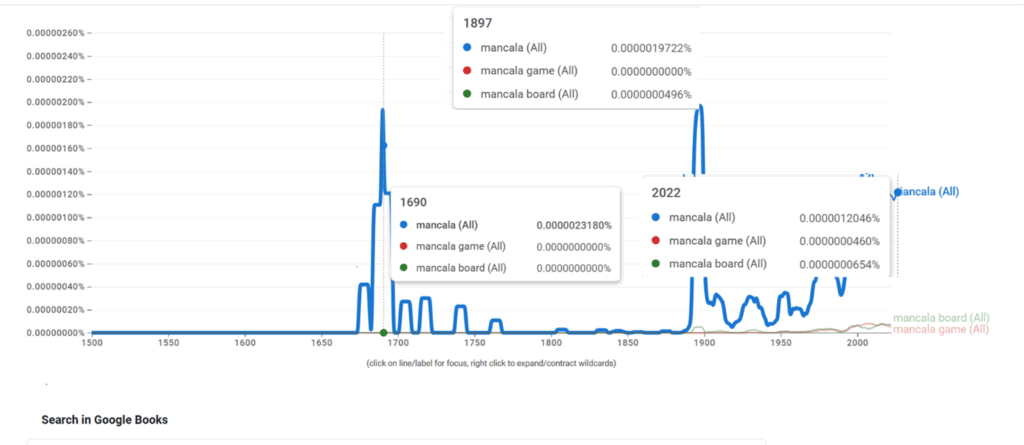

We first examined the historical use of these terms within Google Books database with Ngram, and within JSTOR journal database supported by Constellate, using DfR. We searched for the following words in Ngram and DfR: “mancala,” “mancala game,” “mancala board,” and “mancala African game.” The Ngram results (Figure 1) of the textual analysis ranged from 1500–2022 and indicate that the term “mancala” has been employed by researchers since 1675. This date corresponds to the 17th Century in which Western empires were increasingly establishing colonies in Africa and in other parts of the world.26 Embedded in the project of colonization is the idea that the colonized are irrational, idle, and backward people; it is an individual who needs to “break free from his customary ways of thinking, being, and worshipping to adopt European arts, sciences, and knowledge.”27 We see an increase usage in the 1690s and then in 1897. Figure 1 also shows a slight increase in the years 2000s and 2022, after a decrease in the 1980s. The book by Jean De Thévenot, titled The Travels of Monsieur De Thevenot into the Levant: In Three Parts,28 is one of the earliest references to the use of “mancala” in Google Books database. In the 1900s, John H. Weeks, with his book titled Among Congo Cannibals,29 also employs mancala to describe a game played by the people of Congo. The results further show that the utilization of “mancala” as the name for classic African board games spreads across three centuries (Figure 1). For instance, books that contain the word “mancala” from 2019- 2022 include: Culin, Mancala, the National Game of Africa;30 Daniels, Make Your Own Board Game;31 Huylebrouck, Africa and Mathematics;32 and Ian Livingstone and James Wallis, Board Games in 100 Moves.33

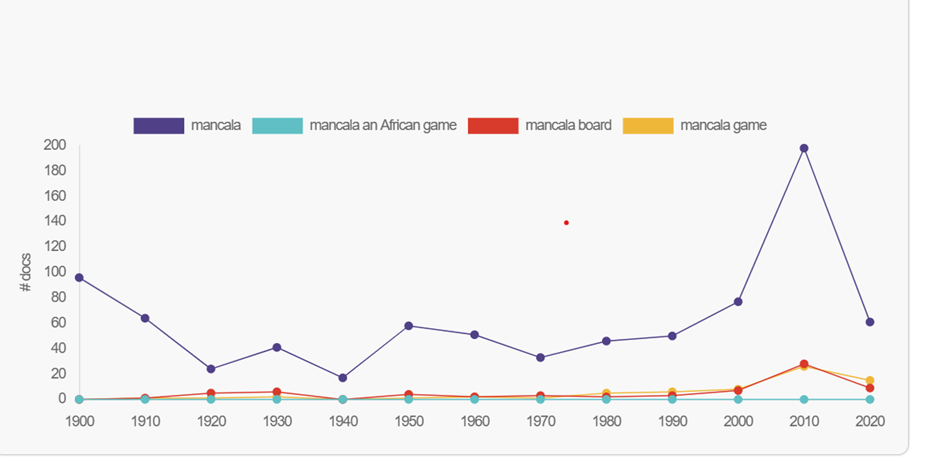

Similarly, we completed a textual analysis in JSTOR DfR in a total of 829 journal articles, from 1900–2024. The findings (Figure 2) show that the word “mancala” was the most used in the literature, starting in the 1900s, with a spike in its frequency in 2010, and a decrease in 2020. The combination of mancala with other terms such as game, board, or African game was not that frequent in the database.

Like Figure 1, Figure 2 signals that in the literature discussing classic African board games, or board games with holes, and played with seeds, “mancala” appears to be the most frequently utilize word. However, it should be noted that the apparent decline in the use of “mancala” in Figures 1 and 2 does not necessarily mean that the term was no longer employed; this may mean that studies on classic African board games were limited during that period. Still, Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate that it is during the European colonial project that the term “mancala” emerged in western descriptions and literature discussing classic African board games. The practice of imposing a different name to these African games appears to have persisted till the year 2022.

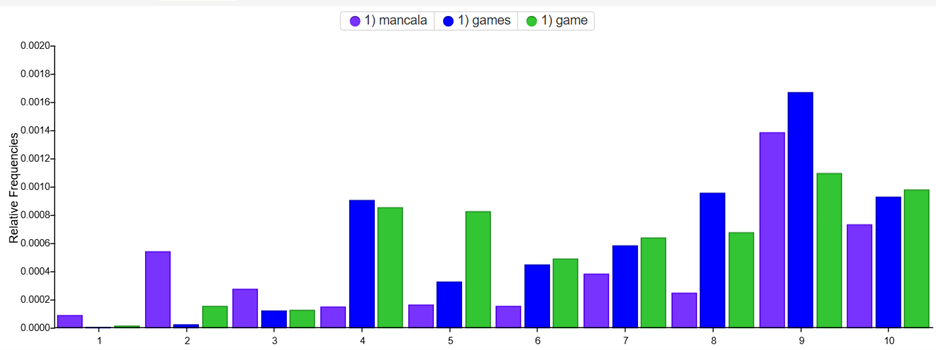

We were also interested in understanding the use of this term in the past five years. For instance, we wanted to take a closer look at the context in which “mancala” has been used in board game research. In other words, we were interested in understanding how “mancala” was employed in relation to other words. The quantitative textual analysis of our data corpus in Voyant, from 2019-2024 (35 articles), shows that the name “mancala” was the most used word (971 times) in our data corpus after the terms “games and game” (Figure 3).

Our analysis also shows that the name “mancala” was often employed as an umbrella word that refers to any game played on a board with rows, and holes as shown in the following excerpts: “mancala is again played on two rows of six holes and sometimes longer rows are attested as well”; “One of the most popular board games that is played in many African countries is mancala;” “mancala” is a broad term referring to a class of board games featuring two or four rows of cup-shaped holes and using various pieces, such as seeds, stones, or shells.”34

The following excerpt further evidences the generic use of mancala to refer to any board game with a board, holes, and rows:

The family of Mancala games is a famous, favorite, and one of the oldest representatives of board games ever … The term “mancala” comes from the Arab word “nagala” for “move” …this group of board games commonly consists of two or four rows of cup-shaped holes (pits) in which a proportionate number of counters (seeds, stones, shells, etc.) is placed.35

Furthermore, our analysis also shows that even in instances where a different name is employed, the name mancala is still mentioned to somehow demonstrate that it is the reference, and most recognizable term for these games.

In Africa, the mancala board game is also known as Bao…Other names given to mancala board games in Africa are ayo, gabata, soro, and Wari…. The name Ayo for a mancala board game is from Nigeria, while Wari is from Senegal… Mancala is a name given to a family of board games… Bao is considered the most complex mancala game played on a board with four-row of eight holes and enlarged holes in the middle…. Bao is played by two people at any one given moment.36

Implications of “Mancala” Use on African Games

The names assigned by the communities playing these games were sometimes present in our data; yet, when mentioned, the word “mancala” was added to indicate similarity or affiliation to “mancala” games family. The term “mancala” has become essential for any research related to these classic African board games. In effect, even when using the playing community game name such as Ntxuva, Ayo, or Bao, mancala is often mentioned to situate the game within the analog game literature. Yet, mancala robs these games of their connection with the communities and ethnic groups they are part of. The term “mancala” participates in the erasure of the history of these ethnic groups or communities. We contend that the name “mancala” is the manifestation of the colonial project that seeks to annihilate African names and beliefs. The various names identified in the literature (e.g., Songo, Boa, Oware, and Tsoro) embody the memory, history, experiences, values, culture, worldviews, and realities of the respective communities. Indeed, these names reflect these communities’ philosophy, conception of time and space. Hence, researchers using “mancala” as a generic term for classic African board games are imposing this term on ethnic groups’ game names. They also ignore or dismiss these communities’ contributions to the history of games, and gameplay in the world. Board game research is colonizing these African communities by using “mancala” as the umbrella for all classic African board games. Yet, these communities game names reflect different ethnic groups and communities’ values, norms, way of being, living, and even approach to life. These games experience in the game studies the erasure that multiple communities in Africa underwent during colonization:

In African culture properly understood, names and labels are central to the human quest for life, development, and fulfillment. They locate both the individual and his/her society in time and space, serving as embodiments of memory, repositories of spiritual and emotional experiences, and expressions of the existential realities of a given people.37

It is worth noting that other names have been used to organize classic African board games: for example, “count and capture” and “sowing games” as other names for these games.38 It should also be noted that historically, anthropological work in Africa has been rooted in the hegemonic colonial discourse that represented Africa and Africans as savage. Ethnographic texts were written by anthropologists that were either “reluctant imperialists”39 or willing co-conspirators in imposing theoretical ideas and practices.40 In these early ethnographic texts, the authors often did not care to know what Africans thought and anchored the African body of knowledge (including their description or classification of classic African board games) within foreign discourses and within “a western epistemological territory”41—there “they remain colonized and thus beyond adequate representation and understanding.”42 These ethnographic texts’ portrayal of African worlds as well as classic African board games are a) distorted in the expression of these realities in non-African languages, and b) modified by anthropological and philosophical categories used by western scholars.43 We argue that even suggesting another generic name for these games, as explained above, implies defining, co-opting, and colonizing these games within Western paradigms, dismissing their African realities, African knowledge, and African conceptual frameworks. Furthermore, suggesting a generic label for these games continues to ask these ethnic groups to express their realities in a foreign language, taking away their agency and their freedom to express their realities in their own terms.44 In the following section, we examine the names of a selected number of games often referred to as “mancala.”

Why Classic African Board Games Names Matter

Classic African board games such as Ayo Olopon, shortened as “Ayo” are often classified as “mancala.”45 Ayo is often assimilated to other classic African board games such as Awele or Omweso, given that the “mancala” label in the literature helps morph them into one identical game. In other words, discussing “mancala” often means discussing all classic African board games. For instance, Maxwell Mkondiwa explains that “there are hundreds of variants of mancala games in Africa.”46 In a similar vein, Alex de Voogt argues, “Mancala games are commonly defined by the appearance of the boards and mode of moving the pieces. The similarities have led to the belief that most mancala games are historically related or that they may be identified by appearances alone.”47

However, the game Ayo Olopon is the name utilized by the people of Yoruba descent in the southwest of Nigeria. Ayo means seeds, whereas Olopon means seed holder. The name is based on the farming structure or agricultural system of the Yorubas, where they were expected to harvest crops and the seeds utilized for the game. Historically, the Ayo game was not just played for entertainment but also for the early mathematical skills to be acquired amongst the Yorubas. The seeds used for Ayo gameplay were mostly from a fruit called “Agbalumo” (also known as the African star apple). Ayo is rectangular in shape and consists of 12 holes (six on each side) with four seeds per hole making a total of 24 seeds (Figure 4).

Oware, pronounced as “O-Ware,” is a popular game among the Akan people in Ghana. It is a game of the ancestors, which was typically played by kings and their collaborators, and is used to assess the intellectual abilities of the respective players and a demonstration of players’ intelligence.48 Ware means “let me marry,” while Oware means married in Akan language, which explains why the game is also played to assess the trustworthiness, behavior, and character of a potential spouse.49 Oware is played with seeds called Oware Aba/Setswana; they are seeds from a tree of a similar name. A popular proverb linked to Oware game reads as follows: “Ntim Gyakari asoa ne man abo no Feyiease,” which means “Ntim Gyakari was a brave man who didn’t respect anyone; for this reason, he carried his own country from Denkyira and destroyed it at Feyiease.” This proverb is often used to state that anyone who refuses to listen to advice will encounter evil or insurmountable difficulties; therefore, it is critical for anyone to listen to elders. The meaning of the game name among the Akan ethnic group, the historical context of its gameplay, and the proverb attached to its gameplay, show the uniqueness of Oware among the Akan. Oware is often in a circular or rectangular shape with 24 seeds and 12 holes (Figure 5).

Morabaraba is a southern African game played extensively by the Sotho, an ethnic group that can be found in both South Africa and Lesotho.50 The word Morabaraba is derived from the Sotho language word moraba-raba which means to go round in a circle.51 Morabaraba is said to have been historically used to teach herd boys strategic thinking and tactics when dealing with cattle.52 The Sotho are known for milling and cattle hearing, and Morabaraba is played by two players, each having twelve “cows” of different colors. The playing pieces being called “cows” speaks to the activity of cattle hearing popular among the Sotho people in South Africa (Figure 6).

Conclusion

The names of the few games discussed above show the relationship of these games with the history and practices of the ethnic groups that have been playing the game for centuries. The name “mancala” used in the literature to group and label these classic African games erases the history of these games and of these communities as well. Indeed, we argue that the use of “mancala” continues to colonize these games often negating the contribution and connection between these games and their respective ethnic groups. We argue that these game names capture the existence of these ethnic groups or communities; the names give to these communities a voice, and a “presence [that] colonialism had done everything to deny, suppress, and ultimately destroy.”53

While we have only used three examples of games to highlight the critical role of names and labels in researching African games, we argue that naming is important for research in any field. The comments made here are relevant to a wide range of fields/disciplines. As shown above, we argue that naming games appropriately can avoid ambiguities, while ensuring researchers accurately represent the phenomenon or object understudy. “Mancala” as a term when employed participate in the colonization of African games in analog game studies, and with this study, we are calling for the decolonization of the field in relation to classic African board games.

–

Featured image from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Game,_Pallaanguzi_1.jpg. CC BY-SA 3.0.

–

Abstract

This paper discusses the term “mancala “and the implication of its use as a generic term for all classic African board games with holes, and seeds. We textually analyzed recent literature on classic African board games; we address the use of “mancala” in the literature. We focused on the names of three classic African board games and discussed these games names and the historical relationship between the game name and the ethnic group to argue that history, culture, and identity erasure happen when mancala is used as a generic term to classify these games. Mancala reflects the dismissal or neglect of African communities and ethnic groups contribution to the expansion of knowledge about games and gameplay. As shown by the literature of different fields, we contend that precise and appropriate use of names limits ambiguity, and even prevents the erasure of a group’s history, creativity, and game design approach.

Keywords: mancala; African classic board games; names; board games; African games, label

–

Dr. Rebecca Y. Bayeck is an Assistant Professor in the department of Instructional Technology & Learning Sciences at Utah State University. She holds a dual-Ph.D. degree in Learning Design and Technology & Comparative International Education from the Pennsylvania State University. Her research lies at the intersection of learning sciences, educational technology, literacy studies, and the interdisciplinary field of game studies. She is also interested in how culture shapes learning and literacy practices in different environments.

Joseph M. Bayeck is a researcher and educator. His research interests are at the intersection of learning, race, and culture. At this intersection, he also explores ways to leverage culture, technology, and mentoring to improve the learning experiences of minoritized student.

Dr. Olu Randle is a Game design Lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. His academic research interests include video and board games design; video games as a tool for preserving African culture and history. He is also involved in the utilization of Machine learning techniques in improving performance of video and board games.