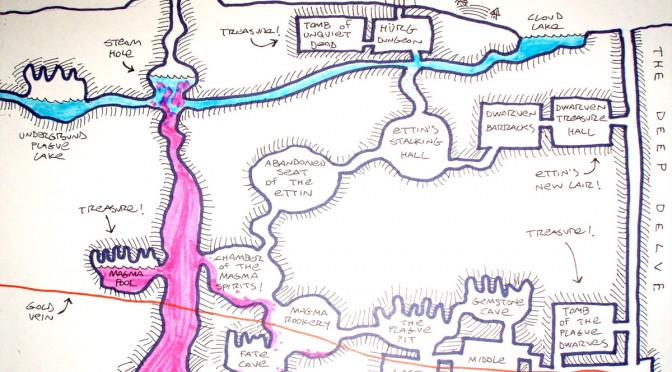

Although the infamous fantasy role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons1 may not seem to be overtly political, its structure and design belie the pervasiveness of the cultural anxieties at the time. In his essay about the ways that Dungeons & Dragons relates to a variety of cultural norms, Matthew Chrulew asserts that the game simulates the bureaucratic tropes of late capitalism in the ways that it affords players control of their environments through an endless set of tables, charts, and figures. Specifically, he argues that the maps packaged in the game are, the most fundamental of all the tools that the dungeon master keeps in their toolkit. “The map is a principle trope of modern fantasy fiction and FRPGs: accompanied by a detailed, descriptive key, it delineates the contours of the imaginary world, imparting both knowledge and mystery,” Chrulew writes. “The freedom of [player characters] to travel and explore the game-world varies, but all is finally determined by the pathways and delineations of the map.” Chrulew explicates how maps determine the action and functions of a site, and I further posit that they also tell much about the cultures that have produced them. While many maps that have been packaged in fantasy role-playing games focus on the wilderness, many others focus on the “dungeon,” which is a notably exotic locale. This essay suggests that the emergence of the “dungeon” as a representational fantasy trope in the 1950s/60s is symbolically related to popular perspectives on nuclear attacks circulating in Cold War America.

The dungeon setting is best fleshed out in the classic Dungeons & Dragons manual, The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures. Published in tandem with the other two core manuals in 1974, the original rulebook had a circulation of only 1000 copies2. In this volume, game designers Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson introduce this interesting twist that had previously been absent from fantasy wargames3 Specifically, they encouraged players to plumb (and design) the depths of the underworld, as opposed to the more common terrain of the wilderness. This was a new addition to a genre that had previously focused almost exclusively on armies clashing in the traditional battlefield setting.

To be fair, the concept of underworld scenography would not have lurched out of the blue for Gygax and Arneson. Though fantasy wargames to this point had been preoccupied with the simulation of grand armies rushing one another in an open battlefield, and scenarios of “defending the castle,” subterranean imagery was also alive and well in both popular culture and the media. Utopic fiction scholar, Peter Fitting, has been instrumental in showing how this genre of fiction far predates 19th century texts such as Journey to the Center of the Earth. Though the genre of subterranean fiction dates back for centuries, traceable to even Dante’s Inferno, it is important to note that there was a strange and significant recurrence of it in 1950s and 1960s media.

Both C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien featured caves prominently in their work. From the dungeons of Moria in Lord of the Rings, to Underland in The Silver Chair (volume 4 in The Chronicles of Narnia), the fantasy genre of fiction advanced a robust understanding of the cave after World War II. Other forms of popular media also featured subterranean societies: In cinema, Journey to the Center of the Earth was adapted to film in 1959, and in The Mole People was released in 1956. Popular television series often featured episodes that took place in caves; Star Trek featured an episode called “For the World is Hollow and I have Touched the Sky” that thoroughly explored the idea of an underground society. These, and other examples, follow what Fitting and other scholars often refer to as the “Hollow Earth” theory, which advances the idea that the center of the Earth is hollow. Fiction that explored the idea did so by conducting thought experiments regarding what sorts of societies might exist underground, and in so doing juxtaposed them against dominant constructions of society.

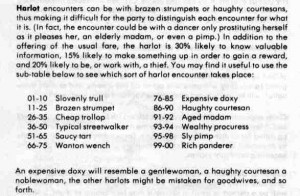

Although the subterranean is often posed in opposition to aboveground terrain, there is a striking similarity between the unpopulated recesses of the underworld and the unpopulated barrens of the wilderness. The wilderness, though never considered safe in our fantasy imaginaries, is depicted as a particularly dangerous environment in The Underworld & Wilderness Adventures; at least as dangerous, if not more so, than the mines of a dungeon. Although about one fourth of wilderness encounters would be with men (as opposed to flying creatures, giants, lycanthropes, animals, or dragons), the types of men one might encounter were concerning, at best: bandits, brigands, necromancers, wizards, lords, superheroes4 and patriarchs could be encountered in the wilderness5. Contrasted with the kobolds, goblins, skeletons, orcs, giant rats, centipedes, bandits, and spiders of the underground6, and it becomes clear how Gygax’s wilderness was no safer than the underworld.

Although the representational space of both the wilderness and the dungeon are equivalently dangerous, it is important to consider the ways in which players are granted control of the space in both contexts. Whether underground or in the wilds, players were given the tools to understand the unpredictability of their environments. With the maps and grids of the game they could see on a table with a birds-eye-view the likelihood of encountering danger in their journey. Furthermore, Gygax and Arneson encourage players to hack the systems they offer in the guide:

There are unquestionably areas that have been glossed over. While we deeply regret the necessity, space requires that we put in the essentials only, and the trimming will oftimes [sic] have to be added by the referee and his players. We have attempted to furnish an ample framework, and building should be both easy and fun. In this light, we urge you to refrain from writing [us] for rule interpretations or the like unless you are absolutely at a loss, for everything herein is fantastic, and the best way is to decide how you would like it to be, and then make it just that way7.

The point here is clear. Though the charts in The Underground & Wilderness Adventures offer a suggestion for how to moderate the realms of fantasy that constitute the realms of Dungeons & Dragons, they are, above all, loose guidelines which are left to interpretation by player and referee discretion.

The representational context of Dungeons & Dragons has undoubtedly become clear. The critters underground are just as alien and scary as those above ground, but, for the most part, those underground are purely imaginary, while real men8 above ground still perpetually engage in violence, skullduggery, and brutality. Furthermore, in all contexts, the fantastic populations below the surface could be controlled completely by interested players. But America in 1974 was an uncontrollable and scary place. Watergate had shown citizens that their government was not to be trusted, there was widespread rioting as the status quo of civil rights was challenged, and the population lived beneath the shadow of the Vietnam War and, even more chillingly, the atomic bomb. The dungeon was a fantastic retreat for a class of mostly white, male, suburban players looking to escape these cultural anxieties.

The fascinating thing about the change of scenery offered by The Underground & Wilderness Adventures guide is that there are few precedents in the community built around this topic. Besides the aforementioned chapters in Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia, there were few games that centered on subterranean locales, a trend that reflects how these wargaming communities had kept to the traditions of the wargame genre even when delving into fantasy role-playing games9. So what could have motivated this deliberate and genre bending turn? In the absence of evidence, it is important to turn toward immanence, and consider some of the popular attitudes of the time around the topic of the Cold War.

Indeed, Sharon Ghamari-Tabrizi (2005) explains in her book The Worlds of Herbert Khan: The Intuitive Science of Thermonuclear War, that life underground was a leading suggestion for nuclear preparedness in the 1960s10. Discussing “The Mineshaft Gap” – RAND strategist Herbert Khan’s suggestion that a post-nuclear America build sustainable communities in mines, made popular in his bestselling book On Thermonuclear War – Gharmani-Tabrizi explains that subterranean development, although heavily criticized and not necessarily popular, was a key discourse in Cold-War America, even being parodied in Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ybSzoLCCX-Y]

Given that other military strategists such as Jerry Pournelle had strong ties with magazines like The Avalon Hill General (arguably a space of discourse which unified the 1960s hobby wargame community) as well as the abundance of veterans also publishing in the same community, it is likely that these ideas were traded amongst the participants in the community. Or, at least, lingering as an informed anxiety below the main discussions of the community. After all, there is a strange symmetry between a seemingly inexplicable turn toward underground mapping and worldmaking, the implementation of these subterranean worlds into a set of simulation mechanics, and the necessity of a specialist workforce to explore, redefine, and eventually refine rock into new commodities advocated by Khan.

And, while dungeons, in this context, serve as the key touchstone in organizing and understanding these new worlds, it is important to think of the ways that they serve as a key act of worldmaking and exploration, too. Players had the opportunity to live out their nuclear anxieties in these role-play scenarios where subterranean society was a distinct and plausible possibility. And with this change in locale, the timbre of simulation was also changed. The systems of representation, epitomized by the dungeon, showcase how the rules of Dungeons and Dragons dealt with far more than just the mapping of the underground. They were instead systems that helped players to manage their affects, and in so doing offer strategies for coping with a variety of Cold War fears.

–

Featured image by Jason Morningstar licensed under CC – BY by Tony Dowler on Flickr.

–

Aaron Trammell is a Doctoral Candidate at the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information. He is also a blogger, board game designer, and musician. He is the multimedia editor of the Sound Studies blog Sounding Out! For his dissertation he is investigating the ways that fan subcultures in the 1960s created the game Dungeons and Dragons. In particular, the importance of affective bonds to their work, and the influence of Cold War motifs on their writing. You can learn more about Aaron and his work at aarontrammell.com.

Hmmmm. I’m sure a large part of the appeal of dungeons to early designers was simply that the movements of the characters could be controlled and chanelled by solid walls, turning the underground into an adventure matrix.

Dungeon mapping and exploration is just easier to manage. City and wilderness adventures are much harder to pull off when you’re a kid, I think.

And I;m pretty sure I understood that, when I started playing at age 12. Going “down the dungeon” was entering into a place where we could have maybe 4 or 5 options of what to do, and many of the outcomes were going to pretty dangerous. Upstairs was “off-screen.”

I’ve got to agree with sjmckenzie. As a Dungeon Master I could never handle the wide variety of possibilities in a town or city. You only had 1 night to come up with another days adventure, so you make a quick outdoor map, make a dungeon or two and fill it with stuff. A town had too many people and too many possibilities.

Our group usually went to the nearest pub “The Green Griffon Inn”, asked the locals for rumors or someone looking for mercenaries, a quick pub brawl and get run out of town by the guards, and the adventure is under way.

I clearly remember my first couple of adventures as a player. The dungeon was a scary place, and our DM was a master of description and suspense. It was great fun.