In this article, we are asking why representations of LGBTQ themes and characters have been so scarce in the context of role-playing games. A preliminary analysis of the first three decades (1974–2005) of English language RPG source material shows that when the topic has not been silenced altogether, it has been met with reactions that seem humorous or extreme in hindsight. Our aim here is to map an alternative history of role-playing game source books, one that pays attention to queer sexualities, and connect these representations to other cultural spheres.

Introduction

Games that deal with sexuality are few and far between, and games that deal with non-normative sexualities are even less common. Generally speaking, games and game worlds have not been inclusive of individuals or themes that are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ; for practical reasons, we will use ‘queer’ to refer to LGBTQ in this article). Explicitly queer content has started to appear only relatively recently in genres where sexuality is considered relevant for the portrayal of the fictional world or the characters inhabiting it, such as simulation and role-playing games.

Although there is substantial research on role-playing games and player cultures that surround them, non-normative sexualities seems to be a topic that still calls for initial study. Furthermore, the various histories written on role-playing games are mostly silent on the topic as well; gender is sometimes discussed, but sexuality is scarcely mentioned at all. In the context of digital games the academic discussion on representation and identification is further along, but since the practices of play are different in analog, social games, that discussion is not directly applicable here.

Despite its long history as something that is perceived as dangerous, blasphemous and alternative, the culture of tabletop role-playing games has remained fairly conservative, especially so when it comes to social issues. However, since role-playing games are shared social game experiences that use textual sources as starting points and not as determining guidelines, the actual practice of role-playing may have had content markedly different from the guidebooks. This article, however, concentrates on the representation of queer sexualities in role-playing game source books, not on actual play practice.

On the basis of an examination of English-language RPG source books from years 1974–2005, our starting point is the observation that queer themes have been either completely absent or extremely sporadic for most of the history of role-playing games. Where the topic has not been silenced altogether, it has often been handled in a way that seems odd, humorous, or extreme in hindsight. In this chronological research article, we will track down both textual and visual mentions and hints at queer sexualities and see how they function within the context of the game. The instances of male homosexuality – as those we initially started to look for – as well as ‘queerness’ more generally are then analyzed as representations in the context of cultural studies and the discussion on identity politics. Our survey is far from comprehensive, and indeed, this article is intended as an opening into a new field of study.

Basics of Role-playing Games

When analyzing characters in role-playing games, one of the most important things to consider is the function of the character position. Game characters vary from being a near-invisible tool (almost like a cursor on the screen) used to implement changes on the game world, to a complex depiction of beings akin to real-like humans with rich personal histories. This progression from a cursor to an avatar to a possible person is tied to the game context. Genre, theme, and general aim of the game play an important part in setting up the context. For example, games focusing on exploration of terrain and violent conquest have less use for multifaceted character constructs than games examining societal issues or simulating alternative social structures.

Today’s role-playing games span this whole spectrum. In fact, as the word role-playing game suggests, one of the most important aspects of RPG is ‘playing a role’, adopting and adapting characteristics in order to become someone else for the purposes of a game. However, role-playing games are not always about nuanced character study. In the dawn of role-playing games play consisted mainly of fighting, exploration of space and adventure, and character development referred to measurable statistics, not growth of a personality. Furthermore, this tradition is still alive and well, even if it is nowadays only one approach to role-play among many.

In the 1970s and 1980s, role-playing games were generally not dealing with societal themes. When RPGs were attacked as subversive and dangerous, the defence was that they were simply make-believe and imagination. Considering the context where role-playing games emerged – a male-dominated wargaming community – it is not surprising that the themes concerning sexuality or gender were not dealt with in the source books. Jon Peterson’s meticulous history of the roots of the original Dungeons & Dragons (1974), Playing at the World, notes that the wargaming community the role-playing hobby grew from was a particularly conservative youth culture. Sexuality was hinted at in the earliest publications, but those instances were quickly removed in later editions. It seems that role-playing games and their source books in the 1970s were based on rather conservative and conformist values.

Indeed, the role-playing hobby acquired its reputation as a dangerous subculture in the 1980s based on its alleged flirting with demon worshipping, not its sexual open-mindedness. A case in point of this is the coverage of role-play conventions by the popular press. For instance, Michelle Nephew notes in her dissertation Playing with Power how this kind of reportage tends to show “aging boys” as awkward and desexualized – while often also including a picture of a token woman, scantily clad. In the popular media, both role-playing games and their players have been considered remarkably asexual for a long time. Indeed, portrayals of Dungeons & Dragons in the media often act as shorthand for males who are overweight, socially awkward, living with their parents – and perpetually single.

The objectified and sexualized women in the visual material commonly associated with role-playing source books have been there from the very beginning. Bare female breasts can be found from the very first edition of D&D. However, there was a clear move away from such sexist imagery by the late 1970s, coinciding with a debate on female character and players. Although sometimes used in imagery, sexual themes did not proliferate in role-playing games. Alas, sexuality was not the only essential element of real life missing from role-playing games. This passage, from the description of clerics in the extremely popular ‘Red Box’ version of Dungeons & Dragons (1983) is particularly telling of the attitude of the publishers at the time:

In D&D games, as in real life, people have ethical and theological beliefs. All characters are assumed to have them, and they do not affect the game. They can be assumed, just as eating, resting and other activities are assumed, and should not become part of the game.

We can assume that sexuality is covered by this statement: ‘it should not be part of the game.’

However, source books and actual practice of play are two separate issues. Playing of tabletop role-playing games are poorly documented, but Gary Alan Fine’s ethnography Shared Fantasy conducted in late 1970s amongst role-players shows for instance that, at least among his informants, raping of female non-player characters by male player-characters was rampant in the games conducted by all-male player groups. The source books only provide the starting point for role-playing games, and they can not determine player contributions and the actual practices of play.

Feeling Your Way in the Darkness

Queer sexualities started to figure in the role-playing game books towards the end of the 1980s. However, in these early depictions, male homosexuality is presented as especially villainous, traitorous, and deceitful. There are also a few scattered instances of characters that can be described as transgender or genderqueer – but also transphobic. There is Slaanesh, for example, the god of lust and excess, who has fluid gender expression and who inhabits the Warhammer fantasy world (from Realm of Chaos: Slaves to Darkness, 1988).

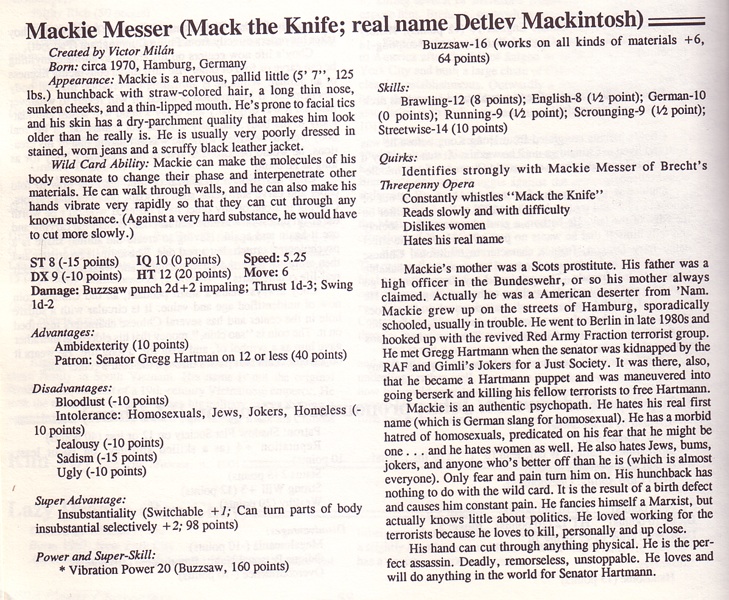

When it comes to the introduction of queer themes, GURPS (Generic Universal Role-Playing System) led the way with a licenced game based on the Wild Cards novels, GURPS Supers Wild Cards (1988). There you could find a closeted gay homophobe, an anti-hero imported from the novels called Mack the Knife. Similarly, in the superhero supplement for I.S.T. International Super Teams (1991), there is a closeted gay man from the Soviet Union (a gay hero living with AIDS was cut from the manuscript, but published online years later). Perhaps the most positive mention of queerness is to be found in Bunnies & Burrows (1992, inspired by Richard Adams’ novel Watership Down), which contains a passage that describes how a male bunny in heat will hump anything, including inanimate objects and other male bunnies.

The earliest mentions of queers in RPG source books are either inspired by mythological or specific fictional texts – or these characters seem to be included for the purposes of comic relief. As HIV/AIDS was becoming more of a social issue in the course of the 1980s and starting to figure in all kinds of cultural texts, hints of it also made their way into role-playing game materials. At times, the moral panic around queer sexualities was very prominent also in the context of role-playing games.

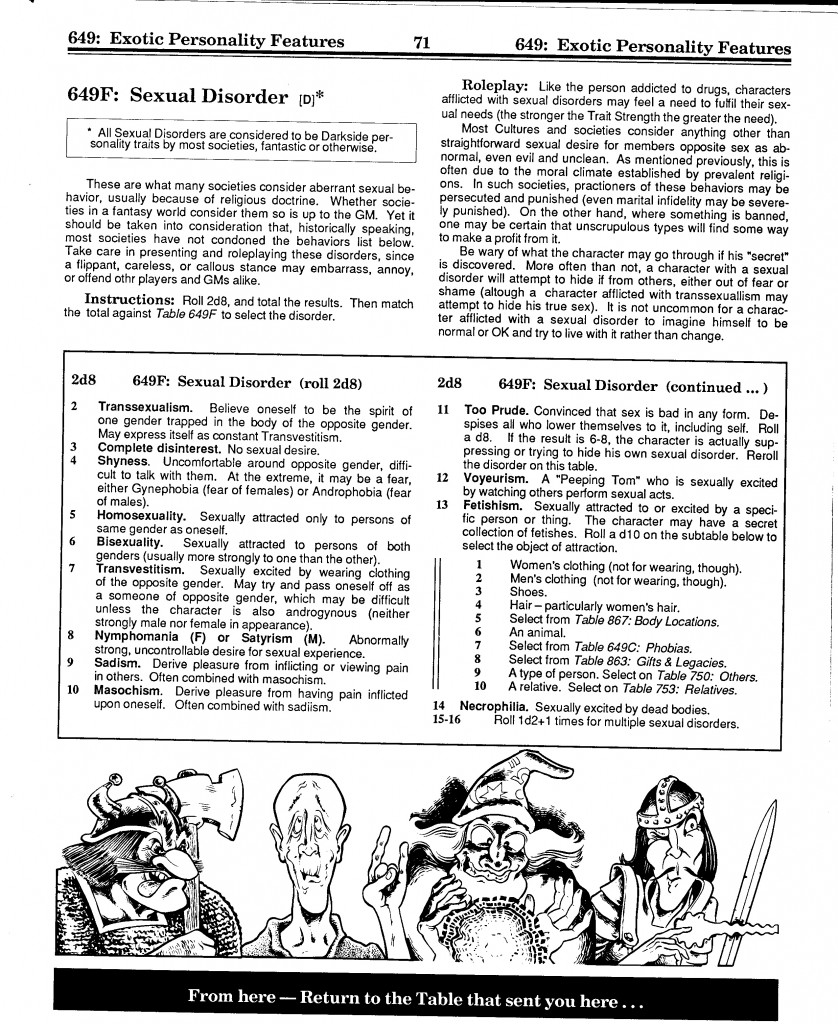

The darkest representation of homosexuality at the time comes from publisher Task Force Games. In 1988 they released a game called Central Casting: Heroes of Legend. In its source book, being transsexual, asexual, gay, bisexual, fetishistic, voyeuristic, or necrophiliac are all listed as sexual disorders and examples of terrifying dark sides of personality.

The same publisher mentions homosexuality in its later works as well. In Heroes Now! (1991), they have a designer position statement that expresses a wish that these kinds of abominations (such as being gay) should not be brought into the game at all. If they for some reason had to be included, these dark features should be played in such a way that they would be awful burdens and obstacles which the player characters would try to get rid of. The game is positioned as having explicit conservative values. When writing about homosexuality and other “perversions”, the game’s authors declare that a sexual relationship is appropriate only between husband and wife, all perversions can be tamed and cured, and using the role-playing game for experimenting with a ‘wrong kind of behavior’ is a very bad idea:

Despite “popular” trends in culture and psychology, the authors of this book believe the following three statements to be true:

- Any sexual relationship other than between a husband and wife is wrong.

- Perverse sexual desires are a form of learned and ingrained behavior and as such can be controlled, overcome and eventually replaced by healthy desires and behavior.

- Using roleplay to vicariously experience wrong behavior is a bad idea.

While we are not called to be judges, it is our belief that those who chose to continue in perverse behavior will ultimately be held accountable for their actions. Those who seek to brainwash society into accepting such behavior as normal are only making the problem worse for themselves and others.

Tables for random generation of events or effects were a widespread trope in early role-playing source books. Such tables were places where queer sexualities and relationship options could slip in as if through the cracks. The Central Casting books are an extreme, explicit example: in Cyberpunk 2020 (1990) there is a table where you can end up creating an ex-lover for your character – of the same sex. Over the Edge (1992) does not have a random table, but a list of examples of secrets a character might have. On the list we can find, “You are gay and feel the need to keep this a secret”, but also “You worked for the CIA” and “You are a cannibal.”

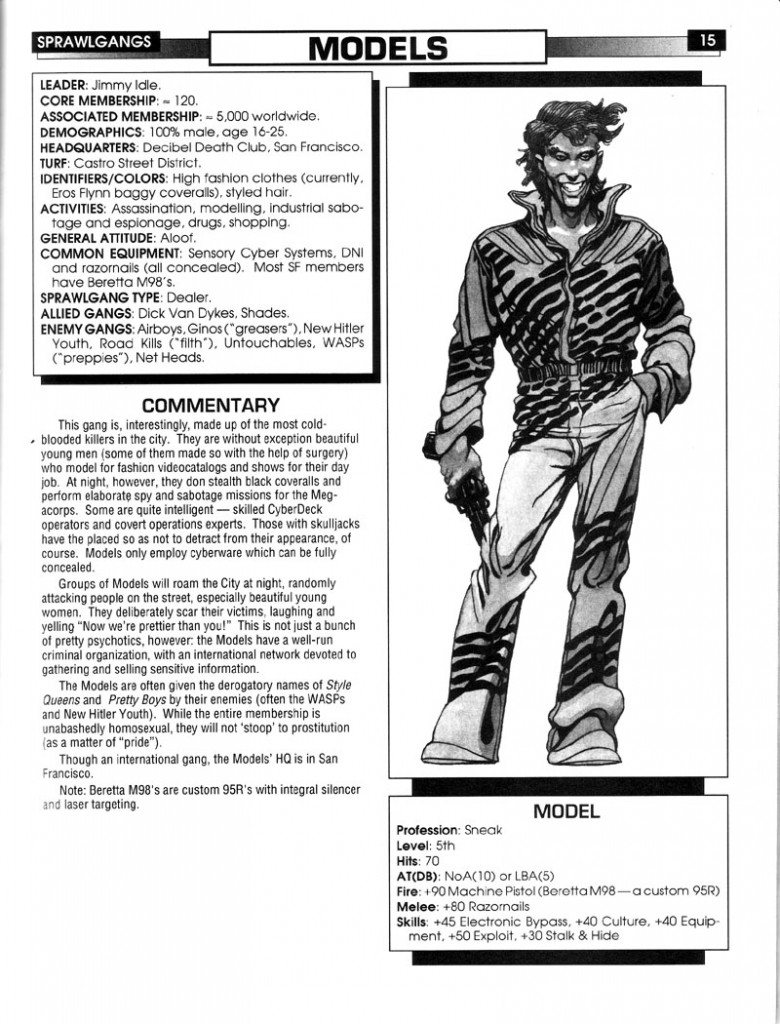

Generally speaking, queer sexualities started to break in more noticeably in games belonging to the cyberpunk genre. A particularly interesting example of gay male representation is offered by Cyberspace: Sprawlgangs & Megacorps (1990). In it a homosexual gang called ‘Models’, consisting of handsome male fashion models, randomly assaults beautiful women in the street. They cut their faces with knives, then point the finger at them and shout: “Now we are prettier than you!” The source book also explains that even though all the members of this gang are openly gay, “they will not ‘stoop’ to prostitution as a matter of ‘pride’”.

These early representations of male homosexuality are interesting in the sense that clearly there was a wish to bring in more contemporary, “adult” themes among RPG designers, but handling such matters was very awkward. It looks like conservative designers felt compelled to include these kinds of themes – while advising against actually playing with them. It is notable that while it is strange to read these storylines and character descriptions today, some of these were ground-breaking at the time of their publication. Later on it has turned out that there were gay designers working on those games, as well, but even they struggled with the narrow-minded politics of representation at their disposal.

There are allegations that some companies, such as Dungeons & Dragons publisher TSR and Warhammer publisher Games Workshop, have periodically had rules that banned the depiction of queers. Although such claims are common, we have thus far been unable to substantiate them. Nevertheless, it does not take effort to interpret the TSR Code of Ethics from 1984 relating to rape, lust, and sexual perversions to also ban queers: “Rape and graphic lust should never be portrayed or discussed. Sexual activity is not to be portrayed. Sexual perversion and sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.” It has to be noted that the general acceptability of these themes has always depended on the games’ target demographics, too. For instance, it is easy to encounter claims that the sexuality of god Slaanesh was diminished by Games Workshop in 1990 when the company started to address a younger player-base.

A New Day Starts at Dusk

A watershed moment in the treatment of queer sexualities in RPGs is the influential game Vampire: the Masquerade from 1991. In fact, the whole game series of World of Darkness (WoD) took sex and sexuality among its main themes. WoD presented players with an unprecedented array of sexual encounter options, naturally including bloodsucking as the principal form of having sex between vampires. These games unmistakably targeted a different audience, one that at least self-identified as more mature and more contemporary than earlier role-players. As Paul Mason has wryly noted,

[…] Vampire and its successors took role-playing out of its core constituency (which could perhaps be pithily, if unkindly, be described as Lord of the Rings-reading social inadequates) and established an alternative fief – in this case that of undead-obsessed ‘goths’.

Indeed, Michelle Nephew makes the argument that White Wolf, the publisher of Vampire, was consistently playing with fears of parents in order to position role-playing games as subversive. The Vampire creators and the audience they attracted presented themselves as ‘alternative’ in every sense of the word. Black-dressing “gothic” people obviously welcomed homosexuals and other queer characters with open arms, even if just to join forces in gaining a subculturally significant status together.

Over the years World of Darkness-related publications not only included suggestive queer imagery (such as the opening image of this article from Changeling: The Dreaming 2nd edition), but they also extensively discussed queer sexualities. Especially the fictional parts which were meant to set the atmosphere and exemplary characters could be openly queer and non-normative. The text of the game is often defiant: these exemplary characters are politically inclined and they evoke ideas of positive discrimination. There is, especially in the early inclusions, an air of tokenism as oftentimes the whole point of having gay characters seems to be having gay characters. Interestingly, one also does get a feeling that many of these roles are actually written by gay people themselves.

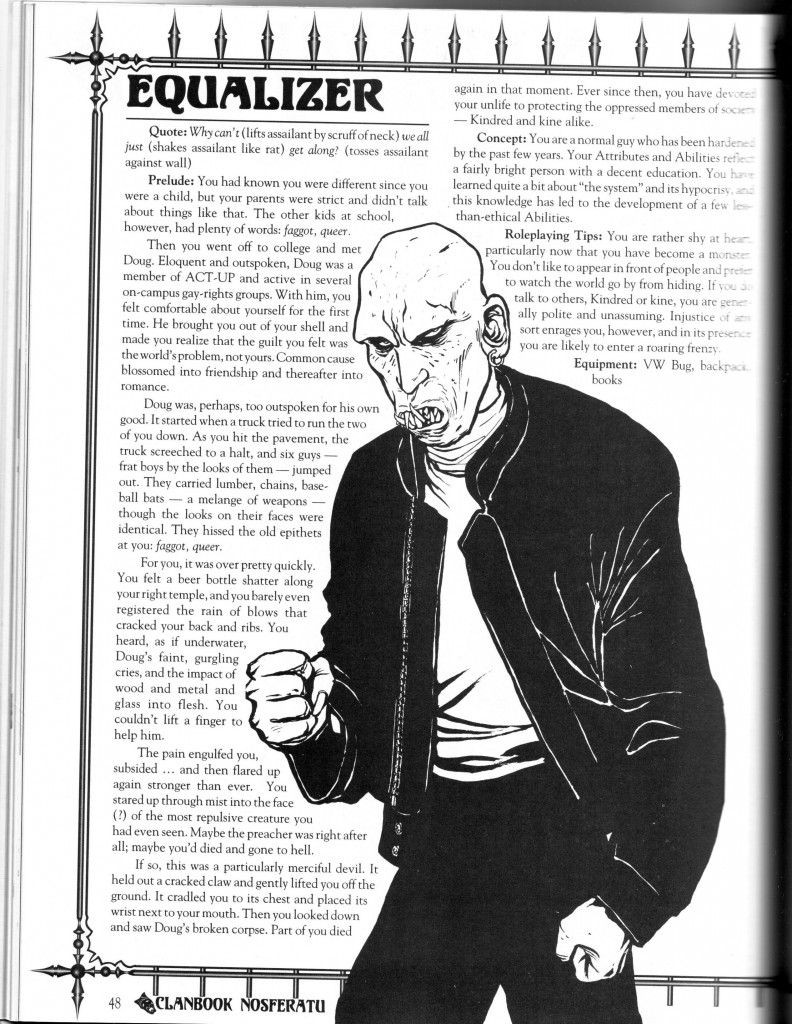

In the 1990s, a lot more positive attributes start getting attached to queer characters in RPGs. For instance, in many source books from this decade the special power of homosexuals is being good-looking. These exemplary gay characters always have more Appearance points than the regular guy. The only officially ugly gay character in WoD is probably in the first Clanbook: Nosferatu (1993) clan book. Even gays are affected by putrefactive blood.

The influence of WoD in developing and distributing positive representations of queer characters cannot be overestimated. In a few short years the depictions of gay and other non-normative characters became normalized and publisher White Wolf had proven its open-mindedness and earned queer credentials. After that gay characters could be portrayed as evil and strange again, but in a more meaningful and humane manner. For example, in Vampire supplement Montreal by Night (1997), there is a gay Sabbat group called Queens of Mercy (that has ties to real world gay history) which beat up straight people. They also organise rituals for which they kidnap regular people, dress them up, and make them compete in absurd things like high-pitch screaming. In the end, these kidnappees are forced to act out the catfight between Joan Collins and Linda Evans from the TV show Dynasty.

Homosexual Fantasies

While horror, cyberpunk, and some other genres started figuring and negotiating queer sexualities during the 1990s, the fantasy genre lagged behind. Dungeons & Dragons remained free of gay influences due to company policy. Not even the brothel description of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons hinted at queer sexualities. Perhaps most striking of all is the lack of homosexuality in Theatrix Presents: Ironwood (1995), which is an RPG adaptation of a pornographic comic with the same name. The role-playing game is surprisingly tame, and only hints faintly at homosexuality.

However, all of this does not mean that fantasy was completely free of homos. Rolemaster: Shadow World (1996) had a gay character and some world description, although only in the web supplement. In the source book of Fading Suns: Lods of the Known Worlds (1996), it is stated that the (fairly strict) church does not frown on any sexual orientation. HârnMaster 2nd edition (1996) has a table relating to character creation, where everyone has a 10 per cent chance of ending up gay or bisexual. In Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play, 2nd Edition (2005), there is an opaque reference to a count having taken a liking to a beautiful young man. Sometimes the references are so vague that they seem almost as if coded, and the designers would only confirm their intentions on internet forums.

The classic Dungeons & Dragons supplement of The Temple of Elemental Evil presents an interesting case. The original came out in 1985 and is obviously queer free. The sequel, Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil (2001) features an allusion to a closeted gay couple, Rufus and Burne. This is the relevant passage, describing their habitat:

An inner wall identical to the curtain wall surrounds this main structure. It has towers with a single gate (same as those in the barbican), creating an inner bailey surrounding a keep, called the donjon. The donjon has four levels with a grand hall, a feast hall, a huge kitchen, many storerooms, an apartment for Rufus and Burne, a vast library, and guest chambers.

We think it is fair to say that this quote does not exactly shout gay. Yet the principal author Monte Cook is sure about it:

It was not the intention of the original creators of Rufus and Burne (who were PCs together and played through the adventure) that they were gay.

However, it was absolutely my intention to portray them as such in Return to the Temple of Elemental Evil (there’s only the one bedchamber for them in the entire castle), without saying “and they’re gay,” which would be silly. (Silly because it’s really not an issue, and because I didn’t identify straight characters as such.)

As social mores were changing and other role-playing games started to include references to homosexuality, fantasy tried to keep up, but in a very covert way. However, player cultures were still not following the books, and that was starting to become visible when player creations achieved higher circulation and visibility due the expansion of computer networks.

Towards Rule 34

In the mid-1990s, as the Internet was starting to figure in the lives of early adopters, fan supplements to role-playing games began to surface. The tone in these web publications was playful, as they featured spells like ‘Mordenkainen’s lubrication’. Some of these had openly sexual themes, such as (the unofficial) GURPS Sex (1993) and The Complete Guide to Unlawful Carnal Knowledge (1996). The latter compared homosexual relations to interracial marriages (such as human-elf) and featured an essay on the topic of, ‘has anyone played a homosexual character’. It also suggested plot points such as ‘reverse rape’ (described as a gay man raped by a woman). The guide contained a tongue-in-cheek reference to choices of professions for gay people:

Homosexuals are, however, rumored to be found in disproportionately high numbers among certain groups, such as adventurers, who have often been driven to adventure because they couldn’t quite fit into normal society, and the priesthoods of faiths which require celibacy, since the priests never need to explain their lack of interest in conventional marriage.

After the year 2000, there was a rush to publish general RPG supplements on sexuality. Some of these tried to take advantage of the open d20 licence, but a “quality standard” provision was added in time to prevent Book of Erotic Fantasy (2003) from being issued under the licence. The book contains a passage that recalls the description of beliefs from D&D red box:

Sexual orientation has no impact whatsoever on a character’s ability scores, fighting prowess, spellcasting, class abilities (with the exception of prestige classes that might require a character to be one sexual preference or another), or other mechanics of the game. A gay character lives, eats, and breathes like anyone else and can be kind, just, cruel, selfish, loving, haughty, or amusing… just like anyone else.

It is interesting to note this supplement explicating that out of all ‘humanoid races, humans tend to be the most diverse sexually.’ Other sex supplements published around that time included a new version of The Guide to Unlawful Carnal Knowledge (2003) and Nymphology (2003); Naughty and Dice (2003) was based on GURPS Sex. Some of books had well-meaning and inclusive takes on queer sexualities, although the texts were seldom particularly insightful.

We’re Here! We’re Queer!

In the early 2000s, the representations of queer identities in RPGs proliferated. Although core fantasy was still largely a no homo zone, most other genres were interspersed with a wild bunch of non-normative characters, too.

Throughout the nineties, GURPS had continued to occasionally feature setting-appropriate mentions of homosexuality. Usually the tone was very matter-of-fact, trying not to make a big spectacle of the gay content. Gradually, queer representations started to become more varied and more prominent. Particularly the publisher White Wolf continued on this track with its superhero game Aberrant (1999), where many of the primary supplements had prominent gay characters, some of who were also tied to the metaplot of the setting. Sometimes the representations went a bit over the top, though. In Aberrant, a wish-fullfilment power fantasy, the wishes being fulfilled are certainly fairly stereotypical.

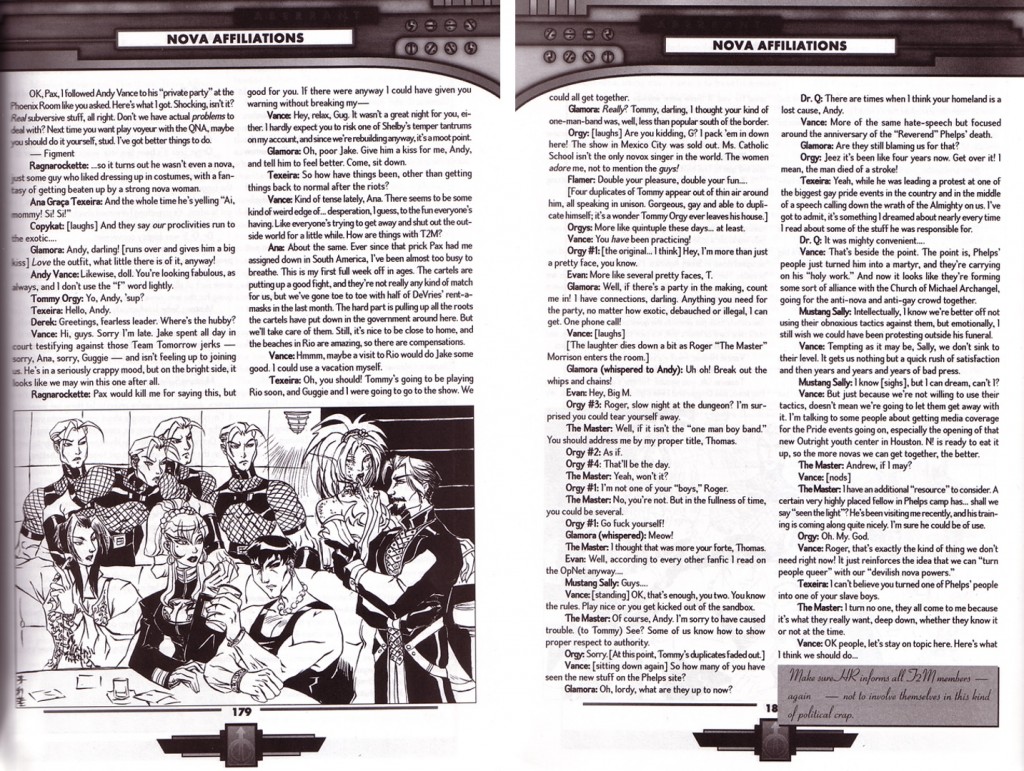

In Player’s Guide (2000), a gay superhero gang Queer Nova Alliance is introduced. Its gang members include a once-bullied nightclub owner from Ibiza named Ironskin, a drag queen named Glamora, BDSM-related character called The Master, the protector of San Francisco named Rainbow, and self-cloning Tommy Orgy. In this game, the most powerful guy in the world, Divis Mal, also happens to be gay, although he is not a member of this posse.

After the turn of the millennium the representation of queer sexualities seemed to start to normalize in role-playing game source books. For example Blue Planet 2nd Edition Player’s Guide (2000), Love and War (2003), Mutants & Masterminds: Freedom City (2003), Unknown Armies 2nd Edition (2002) all feature queer content. It seems that a key factor is the publisher; some publishers (e.g. Green Ronin, White Wolf, Atlas Games, Steve Jackson Games) considered queer people a part of their audience. Sometimes the wording in these source books is still awkward, but the intent seems inclusive, although representations of gay male sexuality are obviously much more prominent and varied than, say, those of transgender people.

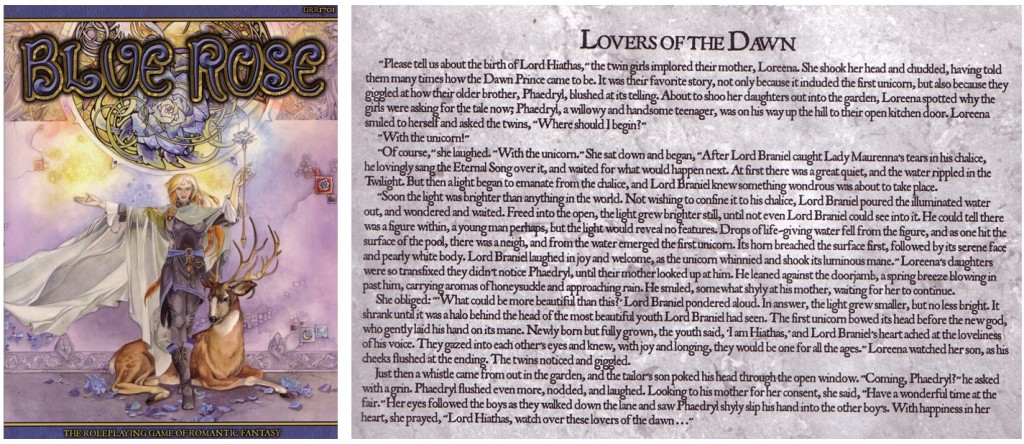

At the very end of the period under scrutiny here is one more source book that should be discussed for its progressive, yet gratuitous depictions of queer sexuality. Blue Rose (2005) belongs to the genre of “romantic fantasy”, and it is decisively targeted at female players. The world it portrays is based on feminist and egalitarian principles in the style of Mercedes Lackey, Diane Duane and Tamora Pierce. As in these books, this game is rife with sensitive and lovable gay boys. The source book has names for different kinds of love – heterosexual (cepia luath) and homosexual (caria daunen) – and makes a point saying that same-sex love was born in myths before straight love. The introductory adventure in the core book features young boys who are secretly in love with each other.

It thus seems that in the 2000s it is possible to have a strongly queer-themed role-playing game out in the market, and nobody thinks twice about it. Whereas in most RPGs queer relations are relatively easy to bypass if the players are not interested in trying them out, in Blue Rose that may not be possible. If one would really try, the same-sex couples depicted in the book could perhaps be interpreted as “just friends”, but rewriting the central world-shaping mythos would take a lot of effort. Why even consider such an option? The discussion on the general acceptability of such queer thematics is clearly indicative of the history of role-playing games, which has not been inclusive or unbiased towards such content for a very long time.

Possible People

On the basis of our observations, it is clear that the role-playing game industry has been rather conservative overall when it comes to representations of queer sexuality. Here we have searched for queer sexualities in role-playing game source books, but a key question remains: Do queer characters matter and if yes, to whom?

More specifically, does representation of queer sexualities – and identification with and as the characters – matter? Adrienne Shaw’s book Gaming at the Edge, an ethnography of queer players of offline digital games, shows that representation and identification are complex issues, and often players do not even seem to care about representation. Based on just reading role-playing game source books we are unable to comment if the same applies to role-playing games. However, if role-playing games are not just about exploration and conquest, but feature societal and personal themes, then we would tend to think that representation and identification have to be important for many players.

The literature on immersion and experience in the larp context supports this, and so does the media panic rhetoric around role-playing games about players identifying too strongly with their characters and getting stuck in them. One reason for this difference is that in analog role-playing games the character has a stronger presence and is more personal as players have more agency in their creation and actions. On the other hand, in one emic theory of role-playing from the discussion forum The Forge, there are different stances towards how a player arrives at the decision concerning the character’s action. Stances include Actor (using only the knowledge of a character), Author/Pawn (decision based on player preference), and Director (affecting not just the character but the environment). It is interesting to note that none of these stances require identification with the character. In terms of play studies this implies that role-playing does not need to be pretend play (playing as if someone else), but can be and often is carried out as object play (play with conceptual objects, in this case characters).

Even if identification were to be unimportant, through the concept of representation it is possible to think about what kinds of existences are possible in games. In her book, Shaw lists three arguments for representation: seeing people “like them” in media, seeing people unlike them (in order to educate about plurality), and seeing who is possible. It is this third category that seems most appealing to us and relevant in the study of role-playing game source books. These books are basically game rules; they delineate what the games and game worlds are like. Having any kind of queer presence signals that the game worlds can and do include queer people. Opening this kind of possibility space seems quite important. However, this remains speculation without proper player studies.

Conclusions

In this article we have started to construct an alternative history of role-playing game source books, one that shows that queer people have been and are possible in various game worlds at least since the late 1980s. Even when the terminology used and values embedded are questionable by contemporary standards, the inclusion of queer people signals the possibility of such lives in fictional settings.

For a long while, character actions and behaviors not directly related to questing and adventuring were not described in the worlds of role-playing games – or at least in the source books these practices were based upon. Questions of faith and activities such as eating were sometimes explicitly defined as not being relevant for role-play, even if characters were representatives of religions and there were rules for the consumption, purchasing, and demand of food as fuel. As these canvases of role-playing games started to become more varied, also sexuality began to play a more prominent role in them. The emphasis was no longer in simply approaching the character as a cursor in a fantastic world, but a plausible, possible character – a persona. Yet queer sexualities were usually completely absent from these texts, or they were in the end associated with derangement, chaos, and evil.

The influence of individual game designers and authors has no doubt been important, even in cases of many of the representations today being regarded as rather negative. The context where some companies had strict rules about the total erasure of queers even tiny mentions may have been important victories at the time. Even the most fleeting mention, a veiled remark, would signal that the game world does indeed feature queer people. However, grasping the importance of such occurrences cannot be achieved through studying the source books alone. Later the influence of player practices has grown, especially as the significance of internet has increased – although player debates in gaming related periodicals were significant from the beginning. It is evident that the more adventurous material usually emerges from fan forums.

It is worth noting that although the presence of homosexuals has grown and the handling of queer themes has become more nuanced during the period under scrutiny, intersectionality is still largely missing. As is evident from the examples in this article, for example male homosexuals are predominantly white. Questions of ethnicity, although present in discussion around fantasy literature, did not seem to influence queers in source books in any significant manner during the first three decades of RPGs.

This is not to say, however, that role-playing games would be disintegrated with the world around them. Relevant to the queer context, the HIV/AIDS crisis was reflected in RPGs, although much of that was filtered through horror literature. Instead of being at the forefront of issues of representation and inclusion, RPGs have mostly followed trends emerging elsewhere in popular culture. Even the arguably most blatantly gay role-playing game from the period under scrutiny, Blue Rose, simply continues the thread where traditionally conservative and conventional role-playing games are becoming more inclusive due to adaptations from other media, in this case a specific fantasy sub-genre interested in gay characters. The Wild Cards RPG was one of the firsts to feature an explicit homosexual character, and Vampire: The Masquerade certainly owns a significant debt to the homoeroticism of Anne Rice’s vampire novels.

To sum up, the early role-playing games silenced queer sexualities completely, on the grounds of not being relevant for the gameplay. An approach that has followed, and that is still relevant, is that of veiled mentions. Queers are possible in the fiction if the reader pays close attention to the choice of words. There have also been blatant, agenda driven uses of queers, both arguing that queers are an abomination, and ones proclaiming inclusivity and alternativity. More recently, the inclusions of queer sexualities have been more matter-of-fact, described without underlining – unless queerness has somehow been a key theme in the game setting. The first three decades of role-playing game source books have shown us, how representations of queer sexuality have moved from the complete darkness of dungeons out into the open.

–

Featured Image: A snapshot of a page from Avery Alder McDaldno’s Monsterhearts (2012), courtesy of Shut Up and Sit Down.

–

Jaakko Stenros, PhD is a game and play researcher at Game Research Lab (University of Tampere). He is an author of Playfulness, Play, and Games: A Constructionist Ludology Approach (2015) and Pervasive Games: Theory and Design (2009), as well as an editor of three books on role-playing games: Nordic Larp (2010),Playground Worlds (2008) and Beyond Role and Play (2004). He is also a popular lecturer on topics ranging from the ethics of designing fictional stories for real-world environments to how sex is simulated in non-erotic role-playing. His current interests include playfulness, the emergence of playing in situations where play is not encouraged, and the aesthetics of social play. He lives in Helsinki, Finland. He can be contacted at firstname.lastname@uta.fi and at

https://jaakkostenros.

Tanja Sihvonen, PhD is a researcher specializing in digital media and games. She is interested in participatory culture, digital labour and the creative industries. She gained a PhD at the University of Turku, Finland, with a dissertation that was positioned at the intersection of Game Studies, Internet Studies and (Media) Cultural Studies. In her book Players Unleashed! Modding The Sims and the Culture of Gaming (Amsterdam University Press, 2011) she focused on player activities and the cultural appropriation of computer games. She has also been studying social games and the transformations of the game industry. After spending many years in the Netherlands, she is currently working as Professor of Communication Studies at the University of Vaasa in Finland.