Game studies–once considered a marginal field–is now over a decade old, and its share of the academic and cultural spotlight grows daily. But all spotlights cast shadows. In 2001, computer games hovered at the margins of what were then emerging studies in digital media. Lev Manovich’s The Language of New Media published that year, for example, focused on the privileged spaces of installation art, hypertext literature, and cinema over any discussion of games as a medium. As digital media studies blossomed, however, computer games suddenly became that which–above all else–exemplified radical new directions in scholarship. In his introduction to the first issue of Game Studies, Espen Aarseth noted that the field should be prepared to encounter both the “Nintendo-Hollywood” industrial complex, as well as open-source revolutions in design and distribution cropping up everywhere on the Internet . Computer games would become essential to understanding the intersection of digital media with popular culture; similarly, nothing could have been more in-vogue than Game Studies, an open-access online publication, dedicated to these games’ analysis and critique.

Analog Game Studies is committed to providing a periodically published platform for the critical analysis, discussion of design, and documentation of analog games.

Now, thirteen years later, it has become increasingly clear that the field of game studies needs a hack: not so much a 2.0, but rather a 0.5. None will contest the fact that computer games are becoming increasingly pervasive in our society. As game studies has come into its own as a field of scholarship, now lying at the margins are the analog games: those very games at the center of foundational texts such as Roger Caillois’ Man, Play and Games or Richard D. Duke’s Gaming: The Future’s Language. Analog games have had their own terminology and prominence for centuries. They are those products that are not always mediated through computer technologies, but which nevertheless exemplify contemporary cultural forms. As Jonathan Sterne points out, the term “analog” only exists by way of negative comparison to the digital, such that our present-day digital forms of expression produce their analog heritage as a by-product. Today, so-called analog games often take a hybrid form, composed of those elements of the digital they might exploit and use: high-quality image editing, social media distribution, and tablet interfaces, for example. In other words, game studies can no longer afford to primarily focus on computer games in an era where the world has become so digitally mediated that the nomenclature ceases to carry the same weight that it once did. Furthermore, analog games are notably detached from many cultural attitudes prevalent in the computer game industry, and can offer an insight into the ways that games work to produce social change. They make clear the rulesets that govern behavior within games and, in doing so, reveal the biological and cultural rules which have forever governed our society.

This is not to say that analog games are more important than computer games, but it does imply that published research in game studies has been disproportionately focused on computer games. Analog Game Studies aims to close this gap.

In business, gamification is the new trend: badges, points, achievements, and leaderboards are increasingly tied to all social media product rollouts. And, like Katniss Everdeen from the immensely popular Hunger Games, consumers must learn the affordances of these systems to ensure what is understood to be emotionally healthy, fulfilling and cost-efficient living in the 21st Century. Applications like Foursquare transform everyday activities like barhopping, dining, and shopping into games, and dating websites like OkCupid offer incentives and points to users who fill in more profile data. Jane McGonigal has spoken from the pulpits of TED on the strategies she has taken to gamify her life in the pursuit of excellent productivity, physique, and balance.

The positive attitude toward gamification in meatspace should be somewhat baffled, however, by the homophobic, racist, and misogynist horrors that continue to ravage the culture of digital gaming. As testified by the Penny Arcade Expo’s “Diversity Hub and Lounge”, an effort at inclusion that was effectively a geek apartheid for women, queer folk, and gamers of color, not all is right in the world of computer game culture. Video games have met with critiques mounted by, for example, Anita Sarkeesian’s web series “Tropes vs. Women in Video Games.” The series was met with death threats and a stream of mindless argumentation relentlessly advocating the merits of a rape-culture that relies on the construction of women as sex objects. What remains is a sad truth: while games are now a clear part of our social infrastructure, they often act as a counter-progressive apparatus in the world today.

Because the barriers of entry to design do not require the technical expertise demanded by the lines of codes which bring computer games to life, analog games hold the potential to allow a new and different set of voices into design processes, voices which might resist the pathological displays of racism, sexism, homophobia, and violence native to the video game industry.

On the point of social justice, it is interesting to note that some of the most innovative and progressive movements in gaming recently have been analog. Independent role-playing games have evolved into a niche publishing industry, and games like Jason Morningstar’s Fiasco or Emily Care Boss’ Under My Skin have greatly expanded what narrative possibilities role-playing games have to offer. Meanwhile, people around the world are taking notice of a vibrant Nordic tradition of discourse and documentation about larp (through conferences such as Knutpunkt and Fastaval and publications such as the International Journal of Role-Playing), while similar practices are becoming more and more common in other play cultures as well (in the States we have the Wyrd Con Companion Books and the recently inaugurated Living Games Conference). Finally, thanks to the popularity of eurogames – epitomized by Settlers of Catan, Carcassone, and Ticket to Ride – fan interest in board games rivals that of computer games at this time, and Internet crowdfunding platforms such as Kickstarter have helped usher in a renaissance of board game development. The Spielmesse in Essen, the world’s largest board game convention, regularly hosts over 150,000 devoted board game enthusiasts each October, more than double the attendees of PAX Prime, the premier video game festival. This is not to say that analog games are more important than computer games, but it does imply that published research in game studies has been disproportionately focused on computer games. Analog Game Studies aims to close this gap.

The argument for game studies began with the point that computer games are important due to their already-extant centrality in today’s media industries. And while this is–if anything–more true now in 2014 than it was in 2001, perhaps the opposite point could be advanced for analog games. Because the barriers of entry to design do not require the technical expertise demanded by the lines of codes which bring computer games to life, analog games hold the potential to allow a new and different set of voices into design processes, voices which might resist the pathological displays of racism, sexism, homophobia, and violence native to the video game industry. In addition, analog games are – except for a rare few blockbusters such as Monopoly or Cards Against Humanity – marginal, and estranged from demands made by the conventional publishing industry (although the indie publishing industry indeed makes its own demands). Many larpscripts are circulated by PDF, and other games still are passed down through oral tradition alone. Because the impetus is on invention as opposed to industry, analog games epitomize the potentials of a design ethic which does not pander to over-generalized market demographics.

The marginality of analog games, however, is not without its own problems. Because these games are often trafficked in underground circles, there has been far less documentation about the practices, and cultures of analog game players. Although certainly work of many of the authors contributing to this blog has gone a long way to better document these practices, Analog Game Studies is committed to providing a periodically published platform for the critical analysis, discussion of design, and documentation of analog games. By offering sharp narratives that highlight the most interesting features of individual games, we hope to increase the visibility of analog games within the sphere of game studies.

So, that’s it! That’s why we’re here. Not to eclipse game studies scholarship, but rather to show how the field’s marginalia have been important and central to the dialogue of games in the 21st century all along. We hope you enjoy the articles we offer each week, and help contribute to a communal conversation by joining us in the comments with your own ideas and perceptions.

–

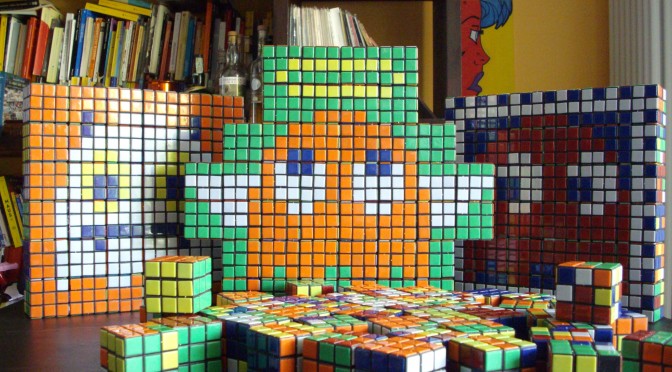

Featured image borrowed from Omino 71 @Flickr.

–

This essay was written by Evan Torner, Aaron Trammell, and Emma Leigh Waldron, collectively and alphabetically (we all chipped in equally!).

Experimentation and Design editor, Evan Torner, PhD (University of Massachusetts Amherst), is Assistant Professor of German Studies at the University of Cincinnati. His dissertation “The Race-Time Continuum: Race Projection in DEFA Genre Cinema” explores East German westerns, musicals and science fiction in terms of their representation of the Global South and its place in Marxist-Leninist historiography. This research has been supported by Fulbright and DEFA Foundation grants, as well as an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship at Grinnell College from 2013-14. His fields of expertise include East German genre cinema, German film history, critical race theory, and science fiction. His secondary fields of expertise include role-playing game studies, Nordic larp, cultural criticism, electronic music and second-language pedagogy. Torner has contributed to the field of game studies by way of his co-edited volume (with William J. White) entitled Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Role-Playing and Participatory Media (McFarland, 2012). He organized the Pioneer Valley Game Studies Colloquium in 2012, and helps organize JiffyCon, Origins Games on Demand, and Western Massachusetts Interactive Literature Society (WMILS) events. His freeform scenario “Metropolis” was nominated for “Best Game Devices” at Fastaval 2012 in Hobro, Denmark, and several other scenarios have been selected for the program. These scenarios constitute part of a larger book project that teaches German cinema through the medium of live-action games. He has also written prose for the Knutepunkt books as well as Playground magazine. He can be reached at evan.torner <at> gmail.com.

Analysis editor, Aaron Trammell, is a Doctoral Candidate at the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information. He is also a blogger, board game designer, and musician. He is the multimedia editor of the Sound Studies blog Sounding Out! For his dissertation he is investigating the ways that fan subcultures in the 1960s created the game Dungeons and Dragons. In particular, the importance of affective bonds to their work, and the influence of Cold War motifs on their writing. You can learn more about Aaron and his work at aarontrammell.com.

Documentation editor, Emma Leigh Waldron, is a Doctoral Student at UC Davis in the department of Performance Studies and a graduate of the MA Performance Research program at the University of Bristol, where her thesis, “Beyond Binaries: Questioning Authentic Identity in Hedwig and the Angry Inch“, explored the concept of performative identities in gender and music through a comparison of the 1998 stage production and the 2001 film adaptation of John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch. Previously, Emma studied Performance Studies at New York University, and earned her BA at Rutgers University where she studied English, Art History, and Theater Arts. Emma’s research interests revolve around the exploration of (in)authentic identity, and performative expressions of sexuality. She is particularly interested in the ways in which these issues emerge in the practices of larp and pornography.