Like any other product, physical manifestations of games come with their share of errors, typos, glitches and other phenomena which possibly undermine the designer’s intention of how the game should be played. Game designers create errata documents to have players “fix” these problems. In this respect, errata work to retroactively enforce the producer’s control over the game. Interpreting errata as paratexts can help us understand corrections within a historical context as well as see them both as a surrounding text and a part of the whole game artifact.

Games are complex entities which can be seen both as systems and processes (activities).1 While the definitions of games are contested and some scholars even question the need for the “ultimate” definition,2 for the purpose of this article we can settle on a basic classification of game constituents – worlds (and the narratives that structure them), rules and play. Errata can emphasize and prioritize some of these “building blocks,” but we should bear in mind that these parts can be neither easily isolated nor changed without altering the game as a whole.

Errata as Paratexts and Preferred Use

Gerard Genette coined the term “paratext” to talk about surrounding texts that inform the reader about the main work, frame the text and also influence the reader’s interpretation of it.3 While Genette focused on literary works, we can easily find parallels between literary paratexts and game paratexts. Analog game errata often fulfill the same functions and take similar forms as “later” prefaces and notes:4

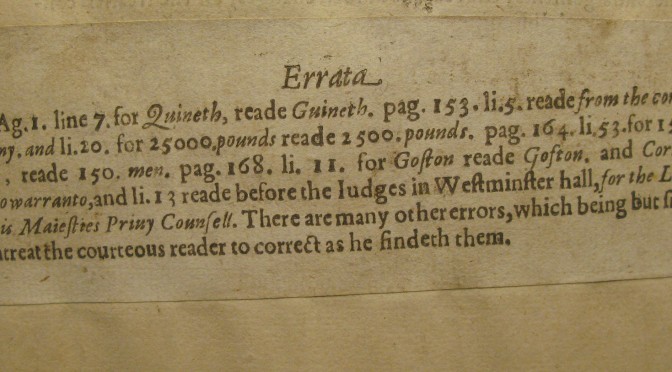

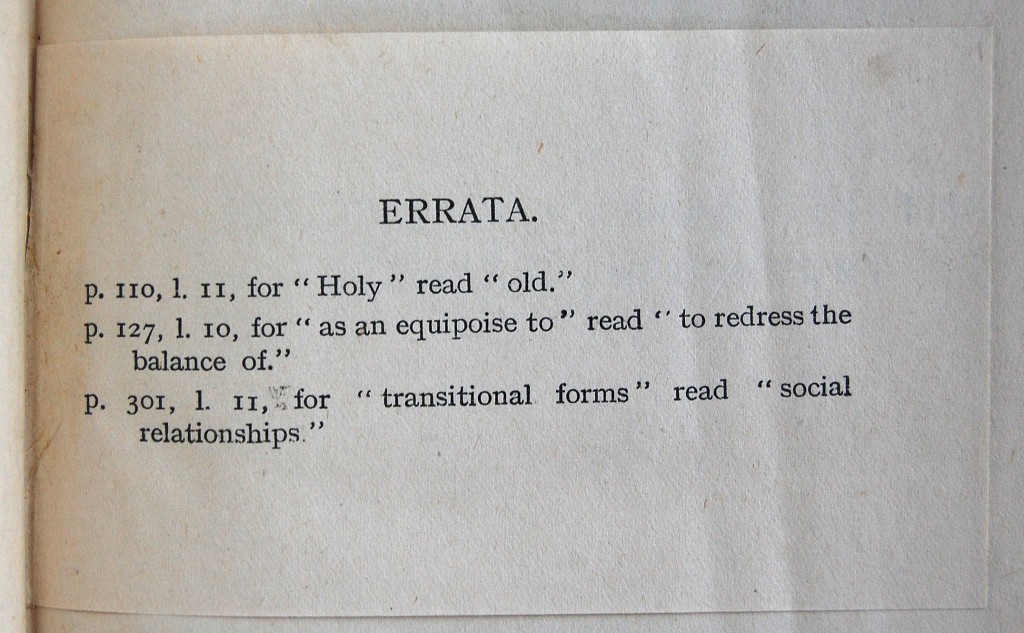

The first minor function [of later prefaces] consists of calling attention to the corrections, material or other, made in this new edition. We know that in the classical period, when it was hardly common to correct proofs, original editions were usually very inaccurate. The second edition (or sometimes an even later one) was therefore the opportunity for a typographical cleanup that it was entirely to an author’s benefit to point out.5

Later notes can perform a similar function of “calling attention to corrections made in the text of this new editions, stressing [the author’s] modesty in the face of justified remarks,”6 even though they usually refer to particular segments of a text instead of a text as a whole. Many physical manifestations of errata consist of such notes put together, as longer texts which, in fact, step-by-step address individual parts of a game.

Pointing out the improvements and corrections is only a minor function of errata. Their main role is to reinforce the preferred use after it was hindered either by designer’s fault7 or unprecedented emergent gameplay: “to rectify in extremis a bad reading that has already been completed.”8 I draw the terms “preferred use” and its opposite – the aberrant use – from the work of Umberto Eco9 and Stuart Hall10 who held similar perspectives on the reception of media content in the 1970s. Any actual play of an analog or digital game can then be positioned in a continuum with both preferred and aberrant uses as extremes. Various levels of aberrant uses can be to some extent predicted and simulated by playtesting, but they are also frequently reported by players interacting with a published game product.

Forms and Distribution

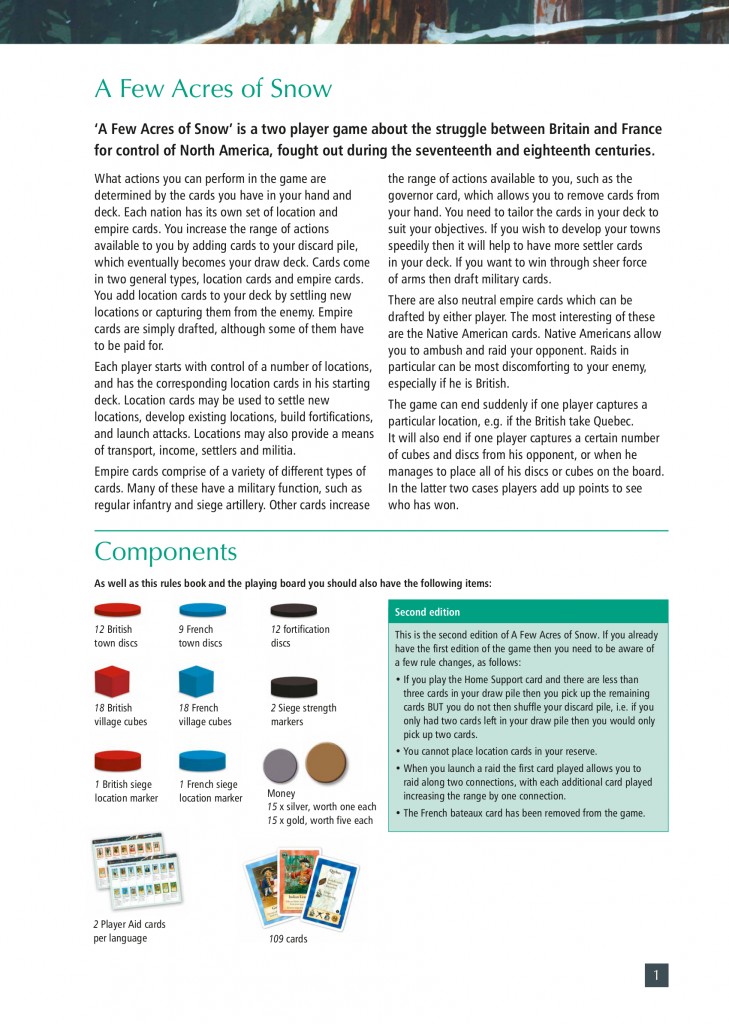

We can trace the default form of errata to the practice of second (or subsequent) editions, also noted by Genette in the context of literary works. Such updated editions often come with the explicit information about corrections and improvements made to a game, potentially becoming an incentive to buy a new version of a product. For example, the second edition of A Few Acres of Snow board game11 comes with an updated rulebook explicitly stating the changes made and also supplying designer’s comments on what led him to such decisions. In this particular case, the errata was prompted by feedback from the Board Game Geek community and various critics who complained about the lack of game balance between the two playable factions.12

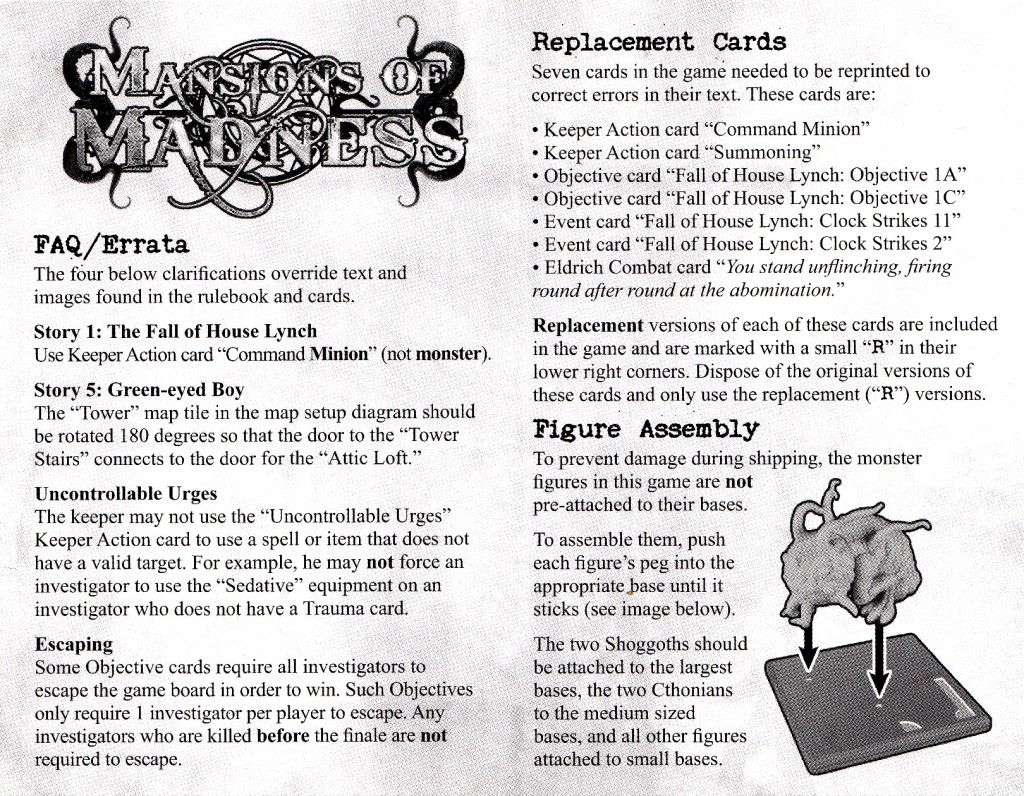

Errata can also be incorporated – if rather loosely – into a game product by way of an errata insert. This form and type of distribution happens thanks to the production cycle of an analog game. Publishers often outsource manufacturing to specialized companies, such that quality control, assembly and shipping can sometimes take place at entirely different locations.13 During the whole production cycle, mistakes and design flaws can reveal themselves, leaving an opportunity to put errata (and any corrected game components) into a box even after the rulebook was printed. For example, the first printing of the Mansions of Madness board game14 included an Errata/FAQ sheet and several replacement cards. Nevertheless, even this paratext could not account for all the errors present in the first printing of the game. Subsequent corrections were distributed via the Internet on the official website of the publisher Fantasy Flight Games in PDF file format.

Digital distribution of analog games errata is a very common practice. Yet this rather inexpensive mode of distribution poses serious problems for players. While such errata may be officially released to anyone interested, the information about their existence may not reach the whole player base. This may lead to potential “bad playing” and an unsatisfactory game experience. We can argue, from the designer’s perspective, that preventing an aberrant form of use is more effective than rectifying it. In this aspect, we can see that video games in general have a much easier position in this form of prevention, as they can often force the patch – along with patch notes that are effectively an errata paratext – onto a player if she/he wishes to continue playing.15

Reception and Response

It is rare indeed to simply release a flawless game that does not require any rule clarifications and errata. One needs errata to both enforce the game’s authorial vision and satisfy players. Reception of corrections, however, can vary from gratefulness to annoyance. For example, the errata insert sheet approach (accompanied by corrected game components) was praised by some players in the case of City of Remnants,16 but it was criticized in the case of Mansions of Madness.17 It is important, however, to note that City of Remnants errata dealt exclusively with misprinted game components, whereas Mansions of Madness errata also introduced alterations to its rulebook. Quite curiously, Plaid Hat Games later released a digital 11-page errata for City of Remnants focusing on rules clarifications. Yet it seems that the first impression of City of Remnants might have experienced a more positive reception, even though – down the road – both publishers had to digitally distribute a more detailed errata.

Audiences may negatively perceive the acknowledgement and the correction of a mistake or a design flaw. But an ongoing ignorance of game’s errors can cause even worse player responses. A conscious approach to errata and post-release support in general can help establish a publisher’s good reputation and influence the sales of future games. Errata incorporated into later editions can also function as selling points to players who haven’t purchased prior “flawed” editions.

We also should not overlook the dual nature of errata as both an isolated paratext and as part of a larger text. Channeling Alexander Galloway’s notion of the interface effect,18 I propose that we not categorize a work’s paratextuality based on the position, structure and subordination of ancillary texts, but rather on the relation between the text and the historical context. In this way, we can see errata as being both an important part of a game – usually of its rules – and also commentary on the social world from which it emerged – the acknowledgment and correction of a game’s flaws vis-à-vis its audience. The paratextual effect may open a game to criticism as it explicates errors, but the textual effect of errata actually maintains the authorial vision and preferred use of a game, therefore controlling its long-term reception.

Conclusion

Errata, rules clarifications and FAQs are a part of analog game ecosystem and – as such – they should not be overlooked as marginal texts made only for the most dedicated players. While the forms and modes of distribution may vary, publishing errata is a common practice within the industry. Both Genette’s paratextual approach and Galloway’s notion of interface effect let us see them as an important tool of designer’s vision and audience management which allows for maintaining a working game system, re-negotiating the preferred use and communicating valuable historical context of an analog game. In this schema, games are no longer static objects, but become unfinished artifacts with histories mutually shaped by developers, players, critics and other stakeholders.

–

Featured Image “Generall History errata” CC wynkenhimself @flickr

–

Jan Švelch is a Ph.D. candidate at the Institute of Communication Studies and Journalism at Charles University in Prague. He received his B.A. and M.A. in Journalism and Media Studies. His research focuses on video game paratexts, glitches, fan communities and fan cultures. His thesis will explore the reception of various paratexts to analog and digital games. Besides research, he works as a freelance journalist covering video games for various Czech magazines. He can be reached at honza <at> svelch.com and some of his texts can be found at his blog http://videogamedelver.blogspot.cz/.