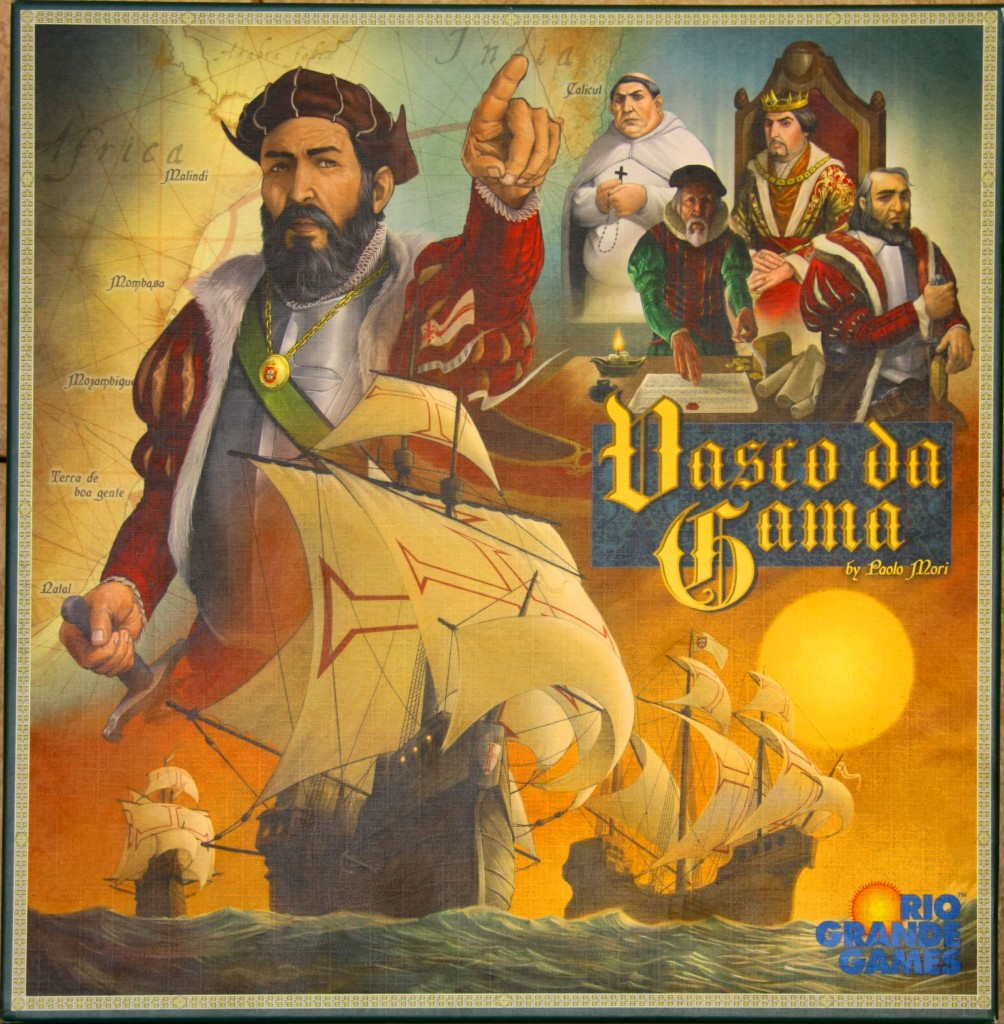

Literary theorist Edward Said once wrote, “The Orient [is] viewed as if framed by the classroom, the criminal court, the prison, the illustrated manual. Orientalism, then, is knowledge of the Orient that places things Oriental in class, court, prison, or manual for scrutiny, study, judgment, discipline, or governing.”1 I suggest here that board games also contribute to Orientalism, shaping what the East is to the West through abstraction and the politics of erasure. While it is not my intent to argue for or against this practice, this essay reveals the political representations of transnational history in play. I argue that this form of representation is not necessarily the result of overt ideology, but rather of the formal properties of the board game medium as such. It is dangerous to laud game design based on form and function without consideration for its political ramifications. To demonstrate as much, I will use Paolo Mori’s Vasco da Gama (2009) as an emblematic case study.

Mori’s work belongs to the Eurogame tradition. In the second half of the 20th century, the genre emerged as a form of board game reflecting an alternate set of design principles and practices. In the monograph Eurogames: The Design, Culture and Play of Modern European Board Games, Stewart Woods recounts that the highest-selling games in post-war Europe were American properties such as Clue and Monopoly, which were owned by Hasbro and Parker Brothers. In 1978, the major German toy publisher Ravensburger began to invest in local game design prizes to help build a successful line of national games that might compete against American products. The most notable of these prizes is – and remains to this day – the Spiel Des Jahres. The contest prompted a creative surge among German game designers, who produced increasingly polished and innovative board-game play. The aesthetic end result could be succinctly described by one of Germany’s most decorated designers, Wolfgang Kramer:2 “Players act constructive in order to improve their own results. They do not act destructive and destroy the playing of their opponents.”3

This game design “arms race” led to a general aversion toward military violence in German board games,4 and was part of a larger cultural shift described by the German historian Geoff Eley: “Guilty remembrance of terrible hardships conjoins with an unevenly-grounded recognition of social responsibility to produce the present breadth of German aversion against war.”5 It is therefore unsurprising that most German-made games of repute avoid standard battle-scenes such as those found in Risk or Axis and Allies. In contrast, American hobbyist games of the same era became increasingly focused on the detailed simulation of war. Such American games often presented entire books of rules on everything from supply lines to firing rates, whereas even the more advanced Eurogame rule-sets are often explained in less than 10 image-laden pages. Eurogames foster different forms of conflict, avoiding the militaristic battles of American wargames by reducing play times, avoiding the elimination of players, and even constraining leading players, so as to keep all participants competitive throughout the game. Despite the turn away from military violence in game design, however, board games of this genre maintain an interest in depicting histories of European conquest. This contradiction prompts the question: how can colonialist narratives exist within Eurogames without reference to violence? Eurogames often contain the problematic presentation of European expansionism without including the indigenous other.

Paolo Mori’s Vasco da Gama epitomizes this phenomenon. Representationally, the game is set within narratives of discovery, sailing, and trade that defined the 15th century Portuguese empire. Thematically, the board indicates to the players that their actions are meant to represent the process of buying ships, equipping them with sailors, and sending them off to Africa. Amongst the players, the best equipped might even make it to India.

Vasco da Gama actually tells us very little about being a Portuguese expedition manager.6 We come to know that sailors went up the coast of Africa and across the Indian Ocean without visiting the Middle East. This is not indicated to us via the rules, but rather by the routes depicted on the map. We know that missionaries were sent on these merchant voyages, but not what they did or whom they met. The rules tell us very little here; if the wooden white figures had not been named as missionaries in the rulebook, players would be left to speculate about whether there was any religious work involved.

Using a term from Ian Bogost’s work on simulation in games, we can inspect the play of Vasco da Gama’s proposed system of “unit operations,” i.e., the subset of functions that make up the system, the game’s mechanics. Bogost’s term helps us investigate games in relation to other media and systems of representation more generally.7 When we appeal to these facets of the game’s design, it becomes clear that Mori is uninterested in representing an account of Portuguese violence. There are simply no mechanics which offer resistance from any foreign entity, as competition consists entirely of inter-European bidding wars. At best, we instead learn how to navigate a strange form of mercantilism reminiscent of current neo-liberal ideology. With its worker placement system, Vasco da Gama occupies the player with timing market logics and compromising the optimal for the possible. Perhaps the most salient unit operation stems from the reward system of the game. Short voyages to the southern parts of Africa are profitable if they can continue up along the coast. Long voyages deliver prestige, but do not return capital. We are never told why. In fact, we are likely to disbelieve anything explained to us, knowing that Eurogames avoid positive feedback loops and probably added such rules to make the game more enjoyable to play. When one considers that this game’s financial success rests on winning awards such as the Spiel des Jahres and is made in the same vein as its contemporary contenders, it likely serves two contradictory masters. If anything, Vasco da Gama communicates despite itself through what it omits: violence. Given that Eurogames offer abstract systemic representations, we might ask what is being abstracted out. In this case – as is often done – the historical recounting of European expansionism is glorified in economic terms, rather than problematized in militaristic ones.

The cultural anthropologist and Islamic scholar Enseng Ho explains that the distinctive characteristic of the Vasco da Gama epoch “was the new importance of state violence to markets… The marriage of cannon to trading ship was the crucial, iconic innovation.”8 For Mori to insert the theme of Portuguese trade into the optimal Eurogame design model, with its short rule sets and intolerance toward warfare, he had to abstract the violence of that trade system out of the game. Though he received critical acclaim (as previously noted), his creation also whitewashes history. Ho continues his castigation of Vasco da Gama’s history, writing:

In addition to plunder and murder, the Portuguese reserved for themselves trade in profitable items like pepper and ginger, thus seeking to ruin the Muslims in all departments… In short, Portuguese colonial and imperial actions were destroying the multi-religious, cosmopolitan societies of trading ports in Malabar, and the diasporic Muslim networks across the Indian Ocean which articulated with them.9

Mori never mentions that Calicut was made a Portuguese trading port through cannon fire. His revisionist history describes his players as “rich shipowners who, under [da Gama’s] patronage, aim to achieve prestige and riches.”10 Though the figure of Francisco Alvares (The Priest) alludes to some element of religion while also providing the player with missionaries, the only reference to violence in the game comes in the depiction of Bartolomeu Dias holding a sword on the game board. Activating him grants the player first turn in the following round, in addition to a few abstract victory points. Tellingly, there is no mention of an “other” who might have historically received the hidden end of the sword.

These representational tropes repeat in several other Eurogames as well. Stewart Woods explains that, in Eurogames, “direct conflict [in particular] is rarely called upon to motivate players as a thematic goal. Instead, the emphasis is typically upon individual achievement, with thematic goals such as building, development and the accumulation of wealth being prevalent.”11 Woods does not address the fact that building structures and accumulating wealth often came at the expense of the other’s wealth and land. Taking violent histories and turning them into resource management/worker-placement games for family audiences creates an ideological fairy tale. Vasco da Gama reinforces a clean and unproblematic interpretation of the Portuguese empire with each play.

Woods writes that the four criteria for the judges of the Spiel des Jahres are:

1. Game concept (originality, playability, game value)

2. Rule structure (composition, clearness, comprehensibility)

3. Layout (box, board, rules)

4. Design (functionality, workmanship).12

Political justice or fair representation are nowhere to be found in these criteria. The award remains important as an institution to watch; Woods cites Scott Tepper, who reports that a typical Eurogame will sell 10,000 units for a nomination and nearly half a million for winning the award.13 If the Spiel des Jahres determines both the field of production and consumption, then it seems that the entire culture of Eurogames aims to be politically disinterested. In so doing, it distorts history and excises guilt from the West. Aaron Trammell has written about this practice of design by competition, explaining that rubrics for game critique often misconstrue games and limit their aesthetic potential. Each of the aforementioned criteria for the Spiel des Jahres, which are nearly identical to Trammell’s case studies (that depict a North American variation of Eurogame design), can be easily subverted for political affect.14 Of course, because market demands lead to these criteria in the first place, the judgments might reflect more a consumerist – rather than design – ideal.

In his essay “Strategies for Publishing Transformative Boardgames,” Will Emigh argues that a zine-style culture is not only possible with game design, but desirable for several reasons. He offers the board game Archipelago (2012), as an example of a mainstream board game failing to produce adequate political discourse, even though it features “natives” who must be forced to work and pacified by player controlled churches. Emigh explains that the game itself is “abstract and it is hard to read a deeper cultural message than ‘there were natives before colonialists arrived.'”15 Emigh’s critique of Archipelago – framing it as an instrument too abstract to mechanically create political justice – is well taken. That being said, however, he goes on to suggest that distribution networks are to blame for the game’s political inadequacies, particularly because of a need for mass-market appeal. On this point, I disagree with Emigh. While it is certainly true that distribution networks affect the cultural products moving through them, different distribution forms offer few solutions when the game design itself elides important political debates.

I remain optimistic. It is entirely possible to imagine a Eurogame of the Vasco da Gama era that does not abstract violence. The form of Eurogames is not so strict as to preclude non-Orientalist representations. The conflation of misunderstood history and the medium’s economic tendencies leads to uninspired modern board games. Surely, the gamewright familiar with post-colonialist theory might abstract other aspects of history to make salient those forms of Western oppression. Brenda Romero has already made several politically informed boardgames, most famously Train (2009). Her works regularly undermine taken-for-granted principles of Eurogame design, such as determinate game length, replayability, clarity, etc. Because these conventions abstract the grotesque from history, Romero makes a practice of subverting them. Unaltered, the Eurogame form may be adequate for remediating some histories, but will fail when relating others. Here, game design should change to reflect histories worth telling. Rather than shoehorning narrative content onto mechanics, these jarring and unexpected rule changes might just make the forgotten and unexpected parts of history all the more salient. My hope is that we challenge design principles and rubrics by revealing how problematically apolitical narratives are embedded into certain game design principles. In doing so, we might prompt game designers to take notice of their Orientalist tendencies among any number of oppressive practices.

Featured image “Colonialism, ” by Aiden Whiteley CC BY-NC-SA.

–

A different point of view on orientalism in gaming (scroll down for english) :

http://faidutti.com/blog/?p=3780