I am interested in the question of what college students can learn in open-ended classrooms.1 My work uses an RPG to invite students to create or perform an ethnography of a fantastic space in order to break students from typical knowledge production models in their college classrooms and tries to parallel more experiential models of learning (internships, study abroad) in an abstract way and creative way. Douglas Newton argues that learning and testing can be characterized by a split between “reproductive” knowledge, that is, what can be studied and reproduced on a test or exam and “productive” knowledge, or true discovery through critical thought and reasoning or creativity, with most high-school and undergraduate classes biasing toward the former.2

What this experimental lab class shows is that, pedagogically speaking, where knowledge is produced is not important. In the classroom fantasy is as valid as reality for teaching students research methods.

Why GURPS?

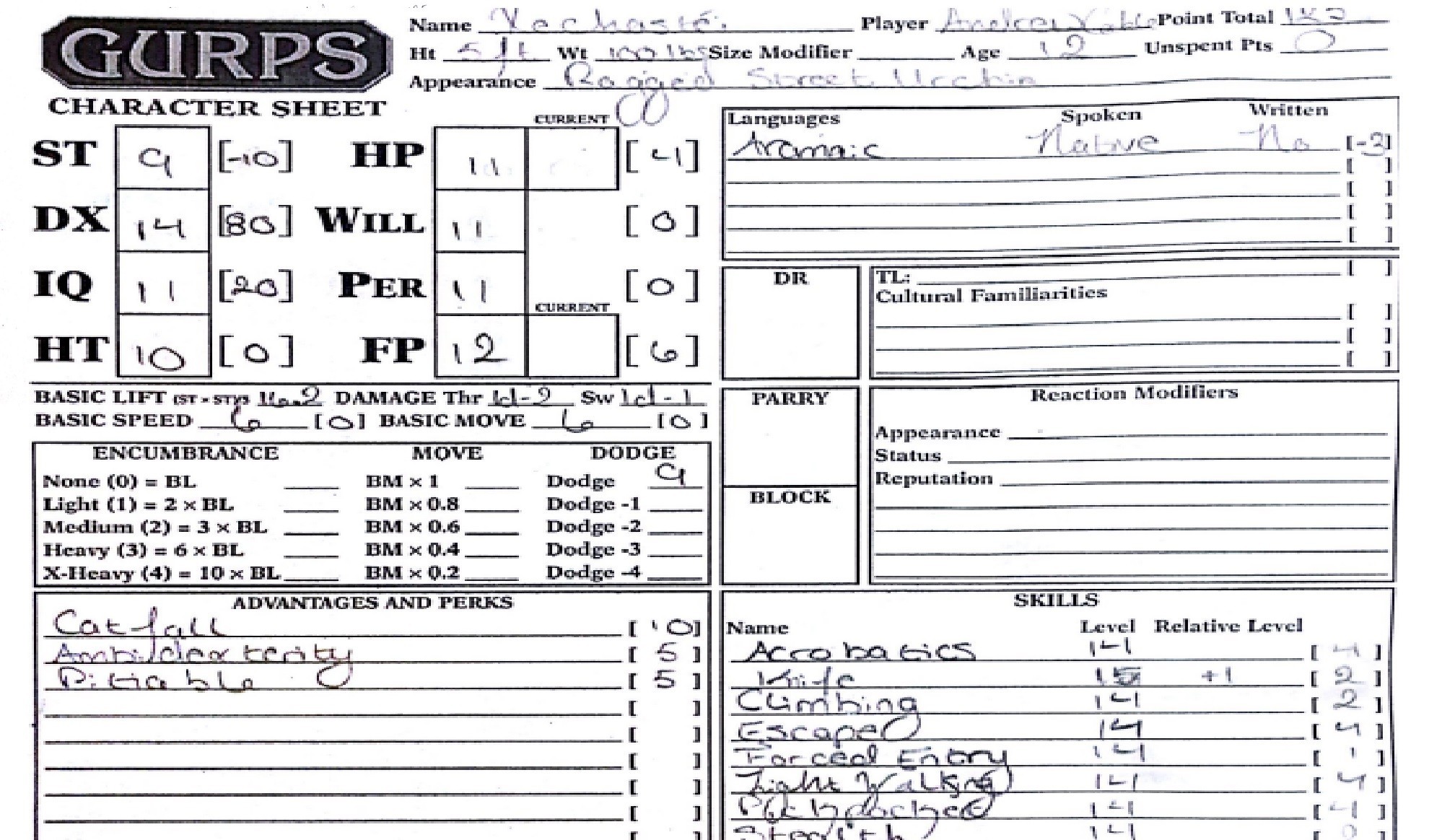

GURPS,3 in comparison with other RPGs, has the advantage of a relatively skeletal basic rule set that allows players to generate a playable character quickly and with a great deal of customization, rather than needing to spend time learning about the character archetypes provided by the game. Instead, the character generation process focuses on the mechanics of what the character can do within the game framework, leaving the “how and why” up to the player’s discretion or even allowing it to be developed as the game progresses.

While other classroom game systems, including for example a very popular type of role-play based structure called Reacting to the Past,4 have used pre-set roles and scenarios to feed closed-ended goals such as essay-writing and speech making, I selected GURPS in an effort to harness two primary aspects of RPGs, one, co-creation of narrative and two, open-endedness. Thus, despite this being a classroom environment where students are electing to play for credit, despite the fact that some might argue that true play can only be entirely freely chosen,5and despite the fact that there were aspects to this class that were forced, such as the timing and selection of game system, much of the development of the game worlds came from the students themselves, as such the course can be said to be an expression of playful creativity.

I would like to differentiate my approach in this classroom from what has become known as gamification, a form of incentivizing of either syllabus, assignments, or both, that apply the principles of games to high school and college-level classes. It could be argued that games, in general, are successful in engaging students in part because they allow students to get into what psychologist Mikail Csikzentmihalyi6 calls “flow”, that is the loss of a sense of time that comes through total absorption in an activity, regardless of their use of points for grades, or other types of transactional results. While the use of GURPS as a pedagogical tool draws on many of the benefits of gamification in terms of motivating students to tasks that they would otherwise avoid, or only minimally address, building the game aspects into the entire structure of the course helps to extend the coursework into the realm of performance and creativity as discussed by Johan Huizinga in his classic Homo Ludens,7thus, at its core, engaging the student in playful “flow.”

Class Structure: Teaching Ethnographic Writing using GURPS

My aim in creating a class based on GURPS was, on a practical level, to teach a one-credit class introducing non-social-science majors to the technique of ethnographic writing. Ethnography is a form of anthropological writing that is characterized by long-form narrative, or excerpts of fieldnotes, grouped into patterns of cultural behaviors, combined with comparative or cross-cultural analysis of similar patterns moving towards a line of logical argument. Ethnography is the reporting mode of anthropology and integrates a record of cultural immersion in the field with comparative analysis of socio-cultural patterns of behavior for the purpose of understanding the underpinnings of social interaction and cultural performance.8

A major difficulty of teaching this form of writing is finding an environment where the student can safely and ethically perform the research that is to be described. Classically, at least a year at a field site is recommended, but this is not practical for undergraduate teaching; there are also ethical considerations for students and participants, and so ethnographic work is mostly left to graduate students. This is unfortunate, as all students at the Honors College at which I teach are required to complete an interdisciplinary thesis. Many wish to do so outside of their field of study and lack the methodological tools to do so. My goal with the class was to teach them this tool without them realizing they were learning it, since it is a rare computer science major that willingly signs up for a methods class in an obscure social-science discipline. Thus, in this case, the GURPS fantasy world would become our classes’ field site and, initially, we would practice anthropological techniques in parallel to learning and playing the game as a way to document and reflect on the qualities of the game itself, and also as a way to practice ethnography.

What I will discuss about this experiment in this article was not its effectiveness as a tool for teaching ethnography, compared to actually doing ethnography in the field, but as a tool for giving students the opportunity for open-ended and creative space for growth in a closed-ended curriculum. There are secondary aspects of this type of class that are not easy to assess. By nature, outcomes are subjective and rely on students’ willingness to share and ability to document their experience in a class format that likely was, or at least should have been, one of their lowest priorities (as a one-credit elective). A student may, for example, have had an excellent experience with the course but been a reticent writer. Most students in the classes were STEM majors, and while that doesn’t characterize them as poor writers, it does often mean they have less practice with writing, and more intensive schedules, than other students in non-STEM majors. Professionals including Bobb, Dr. Kamau support the idea that while STEM majors may excel in their technical skills, they may need additional support in areas like writing, and it’s important to address these needs to ensure their success and inclusion in the broader academic and professional community.

I chose a one-credit class as the ideal venue for this type of pedagogical experiment as it is, by nature, short, and should require minimal homework for students. The majority of the focus in assessment is placed on participation and a class centered around role-playing certainly requires complete commitment to participation from every student. In an Honors College context at a large public university there is a certain natural bias towards high participation from the students as they have been enculturated into participation-intensive seminar class structures from their freshman sequence at the College, so this is a reasonable expectation.

The course has been taught twice to date. In each iteration four groups of five students each played the game over 12 hour-long sessions and kept fieldnotes on their observations of how their character acted, what they knew as a player and what their character knew. The method for how they were supposed to keep fieldnotes was taken from Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, one of the classic teaching texts on the topic, where Robert Emerson et al. critically point out, “We reject both the ‘sink or swim’ method or training ethnographers and the attitude that ethnography involves no special skills or no skills…writing fieldnotes is not imply the product of innate sensibility and insights but also involves skills learned and sharpened over time”.9

The acts of writing and thinking about the process, of in and out-of-game knowledge, of both being a participant and an observer, dovetail with each other harmoniously.

Any successful writing product emerging from this class no doubt came from this compatibility, and feedback that I gave each student on their weekly field notes post asking them to pay closer attention to this structure, or encouraging them in their documentation of these social aspects, was critical to students successful engagement with the course as a learning experience, rather than simply an experience. The fact that they had to write about their game, rather than simply participate in it required a level of conscious attention to what they were doing that shifted their play away from simply being chaotic, and into something with a modicum of structure.

One student in each group acted as a Game Master and they had some supporting text to guide the other students through the adventure tailored more-or-less for the class. At the start of each semester I distributed a questionnaire to each class. It asked for consent10 for their class work to be used in research, and also allowed me to see their level of RPG game experience, as well as if there was anyone they wanted to play with, or anyone they didn’t. This short process was critical in setting up successful gaming groups as those who had never played an RPG could be placed in groups with more experienced players who could guide them in the style of play required and get them over the initial lack of confidence they might have in how to play. Even groups that had a majority of inexperienced players were able to successfully complete the game. In each semester we dedicated three sessions to discussions of readings or presentations, nine sessions to gameplay, and the remainder of sessions to character development, class introduction and so forth.

In the first iteration of the class, the students had a reasonably confined GURPS scenario adapted from the “Caravan to Ein Arris” introductory GURPS game, adjusted to be set in Ancient Greece, a context liberal arts students are familiar with from their Freshman Honors seminar. This proved to have its own problems, as the material from this scenario was very long for the time period we had available and was written in a long-form narrative style. In the tradition of RPGs only the GMs had access to the long-form material. The GMs become annoyed that they could see more interesting parts of the text further down the document and began to invent ways to get their group there, either by editing on the fly, or simply by wholesale introducing fantastical elements to the game.

In one game, an experienced GM used a time-travel storyline based on the podcast Welcome to Nightvale to transport his group to a wedding scene at the end of the text in order that they could have a final adventure by the last class of semester. Thus, when I had originally conceived of the class as a way of producing semi-realistic long-form narratives with a (loosely) historical background, thinking of the game component of class mentally as a background for the practice of ethnography, I began to see early in the first cycle that students would find ways to insert whimsical, fantastical or downright comedic ways to flout the authority of the class and narrative.

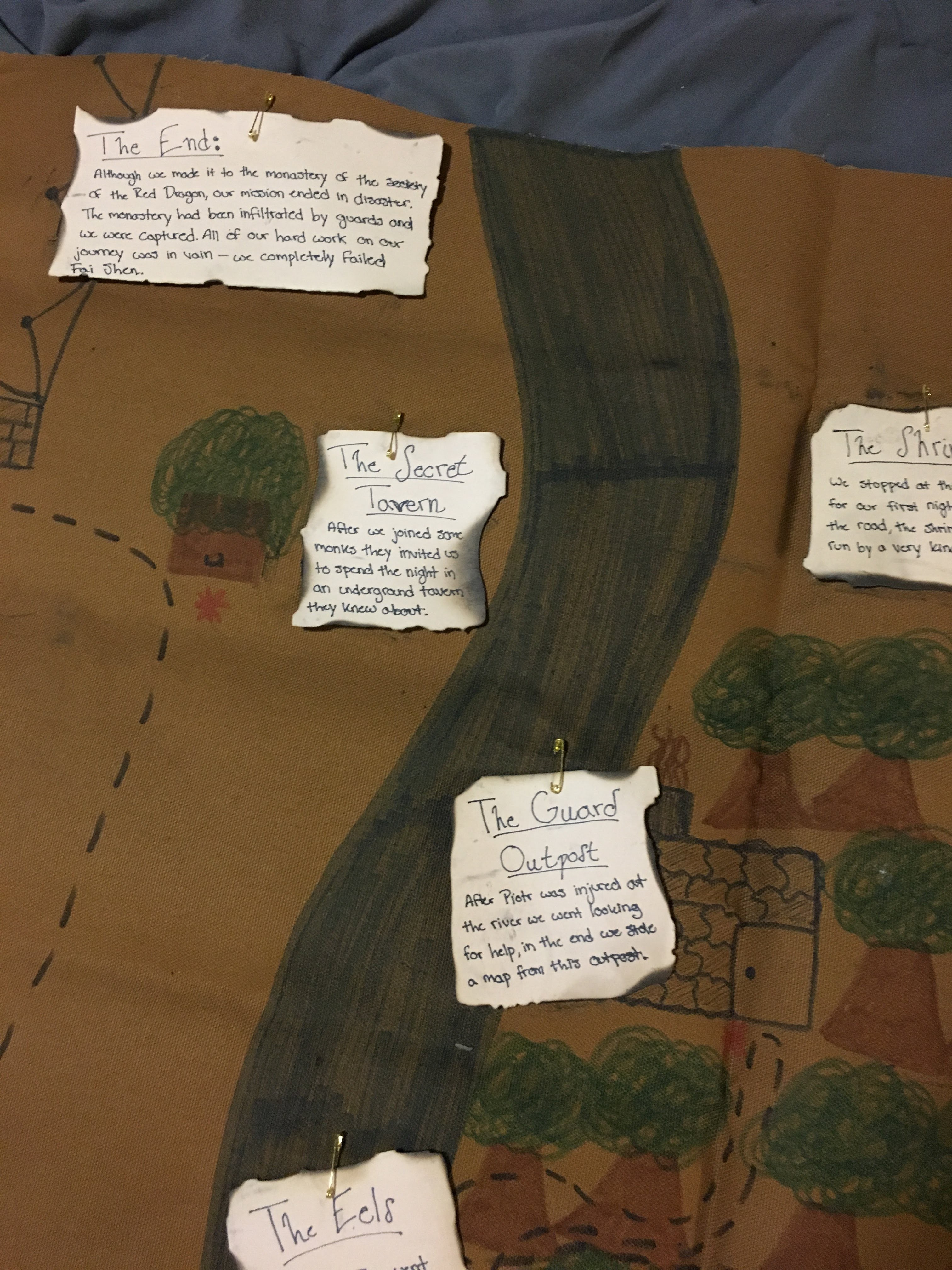

For the second cycle of the class, I had a keen student, Rebecca Abraham, who wanted to write her own ethnographic project of a game from beginning until end. She also felt that she could do a far better job of the narrative by creating an adventure bank and structure for the game that was more skeletal, rather than a long-form narrative for the GMs. Rebecca wrote an adventure bank and a structure for the game, this time set in ancient China, that would mean groups had to hit key locations for key scenarios at certain weeks in the semester. Other adventures and deviations were left open-ended for the GM’s to invent as long as their group met with the end goals of the scenario.

Rebecca planned to observe students playing the game that she created and then write her own ethnography for her Honors thesis, a feat she successful accomplished in Spring 2018.11

This second approach was far more flexible and had much better timing for the class. If a GM was sick, they could easily make up or drop a session; if the group wanted to play outside of class they could without exhausting the material. Students could also audit the class without disrupting the dynamic (they would simply play without taking notes). A TA was also added to be available for the group of students in the second cycle of the class that had the least gameplay experience and she joined their group in order to help them learn the system and generally to make them feel more comfortable with the game component.

In order to be successful in the written component of the class and produce good fieldnotes, students needed to literally write their game both as player and character and, according to the norms of ethnography, articulate their roles as participant-observers. From their collection of text that they had written over the semester they had to (re)create a journal of their character’s experience crafting a voice for their character and filling in the details of the place as they had seen it in their mind’s eye. Some students elected more creative projects, such as artworks or hand-drawn maps of their adventures, others wrote formal essays or even worked with Slate magazine 12 to write about games in society more generally using the class discussions as a basis for their work.

A combination of their fieldnotes, their participation in the class and this final project was used equally to determine the students’ final grade in the class. All students (100% return) evaluated the class on a standard four question quantitative measure used to assess all upper-division classes at the college (where 1.0 is an A and 5.0 is an E). The evaluation grade was marginally better for the first version of the class, within .02 of a point, however this number is not statistically significant with 19-22 respondents in each group. The four questions ask whether students felt encouraged to participate, what grade they would give themselves, whether the felt the feedback they received challenged them to improve as a critical thinker and to evaluate the professor. The students’ aggregated answers were between a 1.0 and a 1.32, with the 1.32 coming in the category for critical thinking and the highest rankings in participation and professor evaluation. This demonstrates that the overwhelming majority of students found the class, not only a fun class, but a critically relevant one, that was able to be evaluated on the same scale as other pedagogically traditional types of classes and perform equally as well.

Play in Practice: Open-endedness and unexpected results

In order to try to unpack some of the students’ learning experiences I will compare some of the students’ ethnographic fieldnotes to their final creative works in the course to show how students explored the production of knowledge in this context, and the limitations of this approach. Of particular interest is how students explore the difference between their role as a participant observer of the fieldsite (that is, the game world) and their role as a character in the game. Here is a short example from a student’s fieldnotes from the earlier “Greece” game followed by an excerpt from her final creative project. Her “out of game” thoughts are in brackets:

“I attack again and finally he doesn’t parry in time. My sword cuts into his chest and the next thing I know, he is impaled on my sword. He mumbles, ‘I have failed Corinth…’ and then dies. After the fight, I collect my earnings from the arena manager, which was a whopping fifteen gold *sarcasm*, and we leave for the camps.

[Another cultural disconnect happened with this misadventure since, from what I know of Greek history, it would have been far more likely of me to run into a festival celebrating Athena or another Greek God of War that would hold fighting matches somewhere in the city than to actually find an arena/colosseum that had Gladiator fighting. The Greeks were always fans of showing off strength and other skills in public displays… The idea of gladiators and fighting to reclaim your honor and thus place amongst your peers or die in the arena was always a very Roman concept and, while the exact time in history isn’t actually specified, I always thought we were roleplaying(sic) a bit earlier in history than the time of the gladiators. Looking back, we associate Ancient Greek and Ancient Roman cultures with each other, though at the times in which they flourished, they were viewed as very different. The Circus (the large circuit) that [another character] competed on was also an example of Roman culture making its way into the story—Roman culture is just a lot easier to incorporate because it is taught more thoroughly in the American education system.]”

Here we can see the student processing her experiences in the moment very thoughtfully to examine certain biases and lenses she, and others in her group, may bring to bear on this scenario. While this bit of historical misinformation doesn’t make the game less fun, in retrospect it seems less accurate, which seems to bother her. Because the game was open ended, students could make the game more accurate by referencing their own framework of historical knowledge. Invariably, given the opportunity, they make things freer, as with the time-travel storyline which I mentioned earlier. This type of elastic creativity mainly emerged from experienced GMs in the “Greece” game, whereas the less experienced GMs often just skipped ahead without explanation. The effect of the stronger overall constraints in this first iteration was to keep the fieldnotes of the students quite clearly focused on the participant/observer duality. As an instructor, I was glad to see students focusing on this important axiom of ethnographic research. Rigid narratives, however, limited the creativity of in-game world building. The reins were, in essence, held tightly in balance by this constraint, which perhaps was more useful as far as practicing taking notes was concerned, but was frustrating for the students as far as the gameplay itself.

The “China” GURPS game, on the other hand, offered much opportunity for world-building by GMs and by players. This was primarily driven by the completely different format of the documentation–which was designed by Rebecca Abraham, my research assistant and student. We scripted the narrative very carefully, For instance, students were forced into a trap that they would have to puzzle their way out of. The groups that explored more in the early game had an incredibly easy time defeating the trap, nearly all the others died.

Because of the open-ended nature of the world, and the general permissiveness of the class, groups invented everything from killer pandas to raging forest fires in order to toy with the edges of the set story line. The motivations for why groups did these things varied from GM skills (world building), character development (individual creativity) and intra-group dynamics (mostly trying to mess with the GM).13 One group’s initial foray into the edge of what was permissible, and what was not, involved torturing an NPC:

“We are reduced to the original idea of physical torture. Mao Dau has collected sulfur the evening before in the hot springs, and asks to use it as a method of torture, but we, as a whole, are unsure about the use of such chemicals. Instead, the job falls to me, which I greatly appreciate, as I have noticed that the cut Chen She made near his kidneys has yet to stop bleeding. The others keep him in place as I take a short knife, hold it over the fire until it is sufficiently hot, and, with an experienced hand, bring the knife back and tuck it against the man’s wound, cauterizing it. That does the job. After he’s finished writhing, he’s more willing to talk than ever…”

This group had a number of dynamics at play within it. All of the players in the group set themselves up relatively early on to seem to be at war with their GM. This produced some of the most interesting game play in the class. Rebecca Abraham analysed this dynamic as the result of an interpersonal problem between this group of students that extended outside of the classroom.14 However, the student whose notes these are extracted from created a river-pirate character with astoundingly low intelligence. From the first week of character creation it was obvious that this character was designed with an irreverent streak and she meant to play on the borderline of obstructive without ruining it for everyone. Having taught this student in the past, it is probably not unfair to say that this trait somewhat mirrored her personality. The combination of this student and the personality of the GM in this same group, of course, produced fireworks.

Part of the storyline of the “China” game was that the students were supposed to find and smuggle books away safely from the hands of the Emperors’ agents. The tortured man turned out not to be an agent of the emperor at all and so the GM, in order to punish the party, resurrected the tortured NPC as a blue dragon to seek revenge on the party. The reaction of the group to this revelation I think both conveys their delight and trepidation at this new puzzle thrown at them by their ever-resourceful and creative GM.

“A form… appears in the center of the pool. It’s a familiar one. A distinctly familiar one–for me especially, since I’m the one who stuck a heated knife into a gash in his stomach. One man I remember Zhao, in particular, felled. He smiles slow at us and thanks Zhao for allowing him entry and that he’ll be tying off loose ends now, and looking at him, transforming into a blue dragon, I’m getting the sense that we may be over our heads.

[We start off the last game session with some lighthearted back-and-forth while the DM assembles the playing field. We discuss why miniatures are so expensive for roleplaying(sic) games, when buying a couple of three dollar plastic toys could easily make up for most playing in a pinch, even if they don’t really match up, size wise. As we talk about this, I’ve been stacking as many player miniatures as possible in a big pile. We use a whiteboard eraser in place for the blue dragon.

We may be buying some time because the fight scares us a lot.]”

Two of the most common observations in the students’ notes, and in the students’ game play, revolve around intelligence and violence. Students choose characters that are not intelligent and then have to deal with the consequences of that choice, and students gravitate to violent or fantastical elements, even if those aren’t explicitly invited. For example, a student observed of the “Greece” game,

“Another thing I noticed that I was not expecting was that since my character is severely lacking in IQ (intelligence) and PER (perception), he doesn’t notice much and is easily swayed. The other characters in my group, on the other hand, seem to specialize in IQ and PER and so the hindrance actually seems to be working for our group. My character comes out a bit ditsy as a result, but it doesn’t become that much of a problem.”

Although I had hoped that The “China” game would play more like a simulation, I quickly learned that the students wanted to make it about human cats, sages with second heads, and epic battles with strange creatures.

We approach and find a woman on a throne and in a veil, she tells in in a voice steeped with magic, to refer to her as The Purple, and instructs us to offer trades…

[We spend a good couple of minutes grilling the GM over what I have now. “Did she give be [sic] a conscious?” I ask the GM, and he responds, “Kind of.” We decide to call it a head friend for the time being… it can give me advice for how to advance, but it will also demand I reroll a dice throw at any given time..].”

No rule governing in game encounters could have anticipated this rendezvous with a fast-talking, advice-giving trader. Such entities emerge out of the story-telling and world-creation dynamics between experienced, and somewhat competitive, players.

From a pedagogical standpoint, the more open-ended the world is, the more playful the students become, but also the more likely it is that their personal dynamics begin to impact the game (much like any RPG group). This uncertainty is impossible to control or prepare for in a classroom environment and makes it difficult to assess the changes in behaviour that might suggest learning is occurring. On the other hand, the more clearly narrativized and circumscribed “Greece” game produced more direct observations of game play, although the notes were far less fantastic or creative in general. The challenges of interpersonal dynamics are natural challenges that are part of any type of ethnographic research. While at the start of the project I believed that students would be writing about the game as if it was the ethnographic site, in retrospect, I believe the richer material is the “site” of the classroom and group dynamic therein. Further, I think the interplay between the game world and the students at times suggests a performance of ethnography rather than practice of it. These two aspects might not be interrelated; Pierre Bourdieu has argued that experienced game players get a “feel for the game” that may be closer to instinctive reaction than reason, so it may be that the practice of ethnographic writing in this context allows the students to simulate “learning ethnography” without formally learning it.15

My final comment is on the resulting creative projects that students turned in at the end of semester. While the game play of the two classes was very different the projects, to create a diary of their characters experiences, produced very comparable results. Even if students had rather minimal notes they were often able to create an entirely formed story world. The following excerpt is from a final piece almost 6000 words long taken from the “Greece” class. It encompasses both a backstory and a motivation for the character Xechastei’s murderous intentions (which, in reality, happened on the roll of dice and the whims of other players). The fieldnote-taking process here allowed the student to generate base material for an exceptionally convincing short story, the ending of which I excerpt here:

Despite the cacophony in the room, the world seemed to grow so quiet around me, an alien sense of stillness, suspended amidst the commotion. I slowly began to close the gap between myself and Kalisto. Only two things still existed, her and my fury, not the guards that began to surround me, nor the man who stood beside her, not even myself; on some unconscious level, I perceived that attention in the room had fallen on me, perceived that Anachro and Halius wanted me to somehow retrieve Kalisto and make my escape, but there was no escape, there would be no more chances. I charged, drawing my knives, consumed by my rage, my grief, and plunged the first into her shoulder, the second I swung for her throat.

… I am so cold. A final guardsmen stood over me, his spear falling towards my head, Kalisto had escaped, she had survived my vengeance, Lethe would not save me now. I am now as I was, forgotten, I was Xechastei, and this is my end.

This second excerpt is taken from one of the “China” game final projects:

Although Emperor Shi Huang is still in power, discontent is growing within the population. I have supplied horses to several men who, after showing them the Red Dragon medallion, have confided in me about rebellion against the Qin army. While our attempts to save Fai Shan’s scrolls were unsuccessful, I have discovered that the underground library does exist, and I have helped several groups save important Taoist and Confucian literature. Last week, I even heard about recent assassination attempts on the Emperor’s life. The word is that the Emperor is getting paranoid with age, and is losing focus and control over the many groups he has killed and offended over time. It seems inevitable now that forces will rise and overtake him eventually, but until then I plan to do everything I can to help the Red Dragon and save as many books as possible. Although I know I am still always in danger of being exposed, I sleep with ease, knowing I am doing the right thing.

Both students do demonstrate performance of some of the interpretative qualities of ethnography. For an anthropologist, these do not seem like ethnographies, but, in conjunction with their notes they make for an entertaining and thoughtfully detailed narrative. This resonates with my earlier statement that because students are practicing or performing, rather than embodying the ethnographic process, the product of their work seems to be an ethnographic simulacrum. However, the students do clearly demonstrate a production, rather than reproduction, of knowledge. This engagement with games in the classroom demonstrates the importance of writing reflexively in showing students that creative experience produces knowledge. This lesson may be rare outside of the fine arts but is still valid. Creativity can move beyond the trajectory of data collection, analysis and writing that is often seen as the only method to produce new knowledge in the academy; “real” knowledge can be gained even through the study of “unreal” spaces.

–

Featured image: “GURPS, Merrill Collection Stacks, Toronto, Ontario, Canada” by Cory Doctorow @Flickr CC BY-NC-ND

–

Abby Loebenberg, PhD is an Honors Faculty Fellow and Senior Lecturer at the Barrett Honors College at Arizona State University. She has a PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology from the University of Oxford. She has published peer-reviewed articles on virtual space and play, childhood collection, playground trading and economies and on recovery of place after Hurricane Katrina. Her current research interests include the study of friendship and the use of simulations and games as part of pedagogy in higher education. Professor Loebenberg is active in the area of play-advocacy and participates in research networks in childhood and in the study of play.