Contested Space: Rulebooks in Hobby Board Games

On July 2019, a poster on BoardGameGeek asked a question on the General Gaming forum about board game rulebooks: “Why do so many games insist on having gendered pronouns in the rulebooks?” The poster noted that their friends had actually drawn a line in the sand, writing, “they’re not interested in learning a board game which only uses masculine pronouns…” The post generated 361 replies, some supportive commiseration, and still other comments filled with a level of anger that surprised us. One poster shared that they were so offended by the use of ‘he or she’ in the rulebook of a top-ranked game that the poster set about writing their own customized rulebook to include only ‘he’ in reference to a player. It was only after this homebrew rewrite that this poster reported they could finally tolerate the rulebook again. Another poster, a high school teacher, chimed into the discussion, with the common argument that masculine pronouns are and always have been the “default” across Western culture, writing, “(t)o many people “he/him/his” has long been viewed as essentially genderless.” Questions of pronouns and gender inclusion in board game rulebooks continue to flare up on BoardGameGeek discussion forums, reddit r/boardgames forums, and on Twitter from time to time. Because these discussions are so common, we felt it was important to establish a scientific baseline from which these claims could be evaluated. Thus, this essay evaluates the efficacy of gender usage in the rulebooks of board games.

We are both active participants in the hobby board game community, and as such we wanted to contribute to the conversations at its center. Tanya has been a board game enthusiast since she was an awkward little kid with a bowl cut in the 1970s. She’d play them all: awful board games, any board games. If you had one, she’d play it. As she grew, she played personally-devastating games of Risk for hours on end, even when she wasn’t sure she even liked any part of it, because pickings were slim. But she was always game. Deep down, she felt a disappointment that she would never see herself reflected in the games of the ‘70s and ‘80s. She was certain she was doing something oddball. She was involving herself in something thoroughly against the grain of gender expectations. Her unease was constantly reinforced by incredulous boys and men, who would ask with surprise, “You like board games?!”

For Shelly, board games growing up were either relegated to those deemed educational (e.g. Scrabble, Trivia Pursuit, Mouse Trap, because she had somehow convinced her parents it meant learning the engineering skills to build a Rube Goldberg machine) or stereotypically gendered games that her brother refused to play (e.g. Dream Phone, Mall Madness). Sitting down to read dreary, confusing rulebooks where players were invariably called ‘he’ was just another way in which we were reminded that we were the exception and not the rule.

Many industries have long since moved on from the “he/him/his” pronoun structure in their manuals, so their prevalence in many board game rulebooks puzzled us. As a former technical and instructional manual writer for the defense and tech industry, Tanya in particular was flummoxed by this recurring debate. If she hadn’t used gender-inclusive language in manuals about loading missile launchers or close quarter combat for the Canadian military, her manuals would have been kicked back to her for revision by the Canadian Department of Defence leadership. It was her job and that of her management to get it right. ‘Right’ meant sharing all information in a gender-inclusive way. Inclusive language remains the gold standard in technical manuals today. For instance, as Tanya worked to get her drone pilot’s license one of her study guides she made a special note that in Canadian aviation law there was a focus on ensuring gender-inclusive language in all materials after an extensive gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) led by the federal government. It found that there was a ripple-effect on gender-exclusive language, and exclusion of women and girls in the transport sector. With gender-inclusive strides and directives in these and other sectors, we wondered to ourselves: why was gender-inclusive language in board game manuals still debatable across online forums in 2019-20? Surely, language would be more inclusive now that it was in early days of gaming. For this reason, we began the process of methodically researching the question of gender-inclusive language in rulebooks.

We believe that board games are for everyone. Though reflecting on our early, stilted entry into the hobby, we see patterns in game manuals that assume an idealized male player. We were curious if rulebooks now would be any more inclusive than they were in the early days of gaming. For this reason, we began the process of methodically researching the question of gender-inclusive language in rulebooks. By taking a quantitative look at board game rulebooks, we hoped to see if rulebooks were using gender-inclusive and gender-balanced language – a fairly simple inclusive practice that, as we will address further, would make the board game industry more approachable for a broader community of players.

Contemplating the long and rich history of board games, we anticipated that we’d encounter a kind of consistency and maturity in the approach taken to game rulebooks, particularly in these top-ranked games. Established sectors, like the military, tend to create a set of standards and reproducible processes, as were encountered by Tanya in the Canadian military around gender inclusion. However, when sectors are young and emerging, there is a greater likelihood that standards are ad hoc, haphazard or even, non-existent, looking to outsiders as a kind of ‘Wild West’ of inconsistency and niche marketing quirks. Smart, simple changes can be beneficial for companies looking to make a name for themselves in a developing market. For example, inclusive pronoun usage has a proven track record of attracting a larger and more diverse customer base. In their study on the use of second person pronouns (e.g. “you”) affecting consumers’ attitudes toward brands Cruz et al., discovered that “the inclusion of second person pronouns in online brand messaging (e.g., blogs, social media posts) enhances consumer involvement and attitude toward the brand” (105). By addressing consumers more directly, companies were able to create a more personalized sense of involvement with their consumers, which positively impacted how they viewed the brand. Something as simple as incorporating the second person pronoun “you” instead of “he” could instill a deeper sense of connection between the gamer and the game as players read the rulebook. Would we find maturity and signals toward broader audience inclusion in the rulebooks of the top 40 BoardGameGeek (BGG) games?

To examine the question of gender inclusion further, we set about trying to audit the current state of rulebooks for the top-ranked board games as ranked by users of BGG. As someone who dabbles in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, Tanya looked at ways to automate the textual analysis process. As with many natural language processing (NLP), the level of variability found in each rulebook made AI NLP difficult to use. It was important to us that we ensured we were being fair, and reading every rulebook on its own terms. We recognized we had to look at each game and rulebook as a whole, and in context. To do that, we concluded that there was no way to fairly create an algorithm or set of search parameters that determined inclusivity, so we turned, instead, to old-fashioned, human-powered textual and content analysis. We read 744 pages of rulebooks to answer the question: How gender inclusive are the rulebooks found in the top 40 BGG-ranked games? We coded our findings using quantitative textual and content analysis, and analyzed them with a rubric that analyzed how gender was approached in language and imagery. We contemplated how a rulebook might be encountered by a reader who does not identify as a man. Our rubric sought any evidence that the rules writers considered the possibility of a woman, girl, gender-non-conforming or non-binary player. Was there imagery or language that presented as feminine in the rules? Were there representations of women, girls, or non-binary folk? We sought any evidence of inclusivity in our analysis and noted it when it was visible. For example, if there was a single image of a feminine-presenting character depicted in the rulebook, even one, the rubric garnered a point in one category. We were looking for any evidence of something beyond the masculine norms, to which board game marketing often defaults, in our analysis. Overall, we observed limited examples of inclusive practices in these board game rulebooks, with a clear dominance of masculine-pronouns over feminine or non-gendered pronouns. We provide significant further detail of our analytic process in the Appendix below.

Before we go any further, we must note some limitations to this study. First, we acknowledge that although our research is limited to gender, it nonetheless has clear intersectional implications. One’s gender identity is impacted and shaped by their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, social class, job status, disability, immigration status and more. As Kimberlé Crenshaw said of her critical framework: “Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects.” We hope that this study offers a constructive starting point toward deepening an intersectional analysis of how identity along gender lines, but ultimately recognize the inherent limitation of this conceit as we examine texts often rooted in a binary approach to gender. For example, our rubric seeks balance and representation when rulebooks rely on the gender binary of “she or he.” We feel strongly that board game rulebooks should be opening up their content to all gender identities, not simply “she or he,” and we wanted to give credit to rules writers who have tried to be more inclusive in their writing.

The struggle for a socially just world is difficult and ongoing. Our intersectional ethic recognizes that gender identity is shaped by other identity categories, which are associated with varying degrees of privilege, and different degrees of access to education. As such, we wanted to build a rubric that identified patriarchy as the problem, and gave credit to those authors who attempted in some way to address it in their work. Patriarchy, as defined by bell hooks, is “a political-social system that insists that males are inherently dominating, superior to everything and everyone deemed weak, especially females, and endowed with the right to dominate and rule over the weak and to maintain that dominance through various forms of psychological terrorism and violence.” If in a rulebook, there was any attempt to recognize the inherent power imbalance (e.g. including multiple pronouns, including feminine-presenting characters, etc.), we noted that in our scoring. That said, we feel that additional research is required to look to at the board game sector through a more expansive frame of inclusivity of all gender identities, and not simply a static binary which is not an accurate capture of the richness, complexities and possibilities of gender expression at all.

Our analysis also focused only on a limited sample of rulebooks, a tiny slice of the universe of 122,100 (and growing) games listed on BGG. BGG is the definitive database that helps us to most closely track the state of the hobby board game practice. However, we understand that all board game enthusiasts don’t necessarily engage with BGG and therefore, the results are skewed towards the active participants of BGG who logged in excess of 1 million votes to elevate these games in our sample into the top ranks of BGG. As such, this sample reflects the tastes of the BGG community which doesn’t represent the entirety of those who play board games. With more time and resources, we would like to look at a larger sample size and determine if the top 40 represents a slice of board gaming that is either significantly better, worse, or fully representative of board gaming as a whole. We understand that this is one tiny, highly limited slice of the research needed in the board game community by academics, designers, and publishers alike. There are many questions raised by these findings and we feel strongly that this analysis is a beginning and not an end. Clearly, further research needs to take on the critical dimension of racial/ethnic representation for example. Dimensions such as disability, age, body type, and many others are also rich areas for intersectional visual analyses. We also recognize that identity and the way representation impacts potential and current members of the board gaming community are complex and varied. We must again reiterate that the pat neatness, and limitations of analyzing gender representation into two tidy buckets of identity: ‘she and he’ is woefully inadequate. As such, readers will need to view these analyses as a kind of blunt instrument, a rough trend line that establishes a systemic pattern. Ultimately, this study invites additional questions, contextualization, and still more research.

Paving the Way For Inclusive Practices

It must be said that the board gaming community is far from alone in its need to transition to inclusive practices, and there is needful debate about how to turn contested spaces, across industry, social and cultural spheres, into inclusive and welcoming ones. As illuminated by Richard and Gray-Denson, 2018, that there is no magic bullet or lever one can pull to ‘solve’ the issue of inclusion. The journey toward inclusion is a complicated, serpentine process full of starts and stops. It is through an understanding of the complexities of intersectionality that help us to understand why there are a variety of responses to oppression and exclusion. Scholars and commentators have identified that there has been a kind of implicit apathy, or an outright refusal from those in positions of power observed within the industry, including platform companies, major publishers, associations, investors and influencers. For some researchers, inclusion starts (but does not end) with representation in the media .

While we would hope that the board game industry utilized inclusive practices, such as inclusive gender in their rulebooks, in order to welcome more diverse players to the table, this is not the only step necessary toward fostering a diverse community of gamers. Throwing down a gauntlet for fellow feminist games scholars, Mia Consalvo issued a challenge to researchers to “illustrate a pattern of misogynistic gamer culture and patriarchal privilege”. Consalvo notes that when she began looking at online gaming spaces in the early 2000s, there was a perception in popular media and gaming that girls and women wishing to engage with video games was an “encroachment …into what was a male gendered space.” Board gaming is in a similar cultural moment, as a broader diversity of players are entering the space and grappling with the same tensions as were observed in the early days of the video game industry.

Our study, once again, takes up Consalvo’s challenge, in our search for systemic patterns. This work seeks to plot a trendline of inclusive (or not) practices in board gaming through a close analysis of analog rulebooks. We situate our work in the wider scholarship analyzing inclusion in digital gaming, and how curation of communities can happen through a variety of intentional and unintentional ways. Scholars have observed that there is, in fact, active curation happening in gaming spaces. This curation is done, arguably, through a set of conscious and unconscious decisions, actions, workflows, omissions, and attitudes that curates the board gaming space into the exclusive preserve of a certain type of player: one that is white, straight, cisgender, non-disabled, middle-class and male. A community is curated, culled or claimed though a set of unconscious, implicit purported ‘common-sense’ approaches to the work and play of games and gaming which signals messages of inclusion or exclusion to women, trans, non-binary and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) players.

There are ways in which contested spaces, contested cultural practices, gendered, racialized labor communicates to people who don’t fit the default mode, who aren’t a member of a dominant in-group; instead, they are the players that they might not be the ‘typical’ gamer, and that they may not be welcome. A lack of representation found within game texts and imagery is another of the “invisible ropes” that might prevent diverse gamers from entering the space and engaging fully in the hobby or the work of creating games. As some games scholars have noted, there are ways in which contested spaces, contested cultural practices; racialized labor communicates to people who don’t fit the default mode, who aren’t a member of a dominant in-group; instead, they are the ‘Other’; and are, as such, their presence is often perceived as transgressive Our study seeks to examine another invisible rope that may, intentionally or not, limit the players invited to the table: the use of pronouns and imagery.

The lack of representation of BIPOC and women in media has been well documented. Looking at additional studies that focus on diverse representation as well as the use of gendered pronouns allowed us to 1) understand the impact pronoun usage has on readers, 2) compare approaches different fields took in addressing readers in instructional materials. For example, in their study on news media messages, Senden et al. discovered that the pronoun “he” appeared nine times more often than “she,” indicating “that men are represented as the norm in these media” (40), while women were often reduced by essentializing language that portrayed women as representational of their gender (e.g. “female athlete” as opposed to “athlete”). The study, which examined 400,000 Reuters news messages also reiterated that “media often represent women as ordinary people, whereas men are represented as experts and/or possessing power and high-status positions,” reinforcing denigrating stereotypes based solely on gender. A 2018 analysis of board game artwork in the Top 100-ranked BGG games found that white male imagery was overrepresented relative to North American population demography on the side panels front and back covers of these top-ranked games. In these explicit ways, media enculturates and educates members of a community about what their expected gender roles are, their position in society, how they should behave, and act as a cue for certain gender identities to opt in or out of certain pursuits.

Media helps people understand their society and themselves, and the media is a source for sharing beliefs, values and ideologies. While analyzing French technology education materials, Colette and Marjolaine found that students who identified as women perceived an abundance of male-gendered objects in textbooks, which “strenthen[ed] the girls feeling that teaching of technology is more adapted for boys than girls” (15). Colette and Marjolaine argue that science and technology project “a masculine image, not only because men still dominate the field, but also because men dominate the language and images found in scientific literature: exclusionary language in textbooks and lectures, reinforced by illustrations that emphasize almost exclusively the role of men in science, serves to project and perpetuate stereotypical images and biased behaviors” (3). Similarly, analyzing computer science educational materials, Medel and Pournaghshband argue that the use of male-centered imagery and language perpetuated gender inequality and contributed to low participation among women and women students experiencing low confidence in their ability in computer science. Making didactic tools like textbooks and rulebooks inclusive, authors can encourage participation by marginalized folks in the field and increase their comfort level with, and perhaps mastery of, the material presented.

A Canadian government initiative led by the Status of Women Canada launched Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) sought to look at how government programs and policies might be experienced by different gender identities and other socio-cultural differences. When the language of a sector disappears the participation of an entire gender, that sector tends to see a lowered participation of that gender. The use of language is one way in which certain groups might be included or excluded, and so, at least in the Canadian government, careful attention is paid to ensure all socio-cultural and gender identities are included in official written materials and policies. In multiple studies on student success, exposing individuals to the objectification and stereotypical portrayals of women has been linked with poor student participation and lower academic performance. Researchers simply mentioning that women weren’t good at and didn’t score well on a standardized math test actually lowered the scores of women test-takers in the experimental group, while women, in the control group, who weren’t given that negative, gendered performance message scored similarly to test-takers who were men.

How does representation, linguistic and otherwise impact board gaming? Game rulebooks can determine how players experience a game. Rulebooks can even determine whether a player ever plays a game at all. These guides can instead act as a kind of gatekeeping mechanism; poorly written, confusing and vague rulebooks can break immersion and impede the enjoyment of a gaming experience. Badly written rulebooks can necessitate a need for players to take matters into their own hands, constructing errata, additional frequently asked questions (FAQs) and house-rule variants to solve issues in the rulebooks. These issues can literally exclude players from engaging with the game at all. Rulebooks can also send messages of inclusion and exclusion in other ways as well. Persistent negative or limited representation of women in board games, whether it be in imagery, playable characters, or pronouns in a rulebook, can render some women reluctant to participate in the hobby. Allowing people to see themselves represented in an art form or a cultural pursuit is, as argued earlier, an effective way to invite people in. It can also send a message: that other demographic groups are welcome but they are also valued, respected, and even safe. As Wentling argues, “Language is a system of power. It socially constructs that which has meaning and therefore has the potential to affirm or deny personhood” (470). If individuals are invited into linguistic spaces like rulebooks which use language that accurately portrays them, they will be more likely to engage in these communities.

This message of exclusion can be sent in myriad and insidious ways. Suzanne Sheldon of The Dice Tower that the wargaming term ‘dudes on a map’ is gendered. She noted, “‘Dudes’ and ‘Guys’ are GENDERED TERMS (caps in original). They are not gender neutral. They are masculine terms that have become (as masculine terms often are) the default for a mixed gender generalized term. Please do not argue with me that “Dudes” is neutral.” Sheldon presented an elegant solution to this problem which is to replace, ‘dudes’ with ‘troops.’ Et voila, you have troops on a map, and not even an extra syllable’s worth of extra effort to solve that problem. Moreover, this variant renders the reference more accurate, as generals, armchair or otherwise, rarely order their ‘dudes’ into combat. However, Sheldon did get pushback on this simple suggestion, with posters who argued that ‘dudes’ wasn’t a gendered term at all. Yet, there is a growing chorus of voices in board gaming that the hobby and the sector needs to pay close attention to matters of equity, diversity and inclusion.

Top 40 BGG Rulebooks Findings: What Did We Uncover?

To answer our research question, “How gender inclusive are the rulebooks found in the top 40 BGG-ranked games?” we looked at a number of factors in the sample, the publication year, country of origin, and the publishers. Our analysis sought relationships between relative scores and the publication year, country and publishers and here’s what we found.

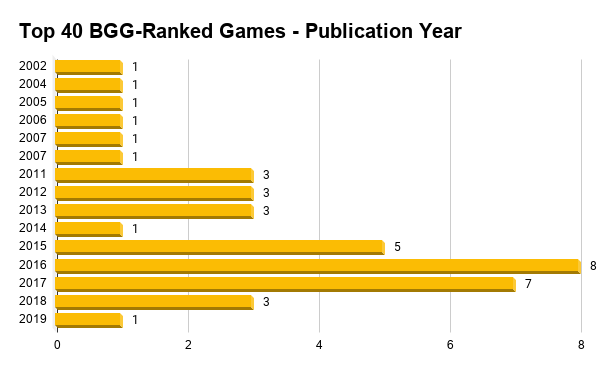

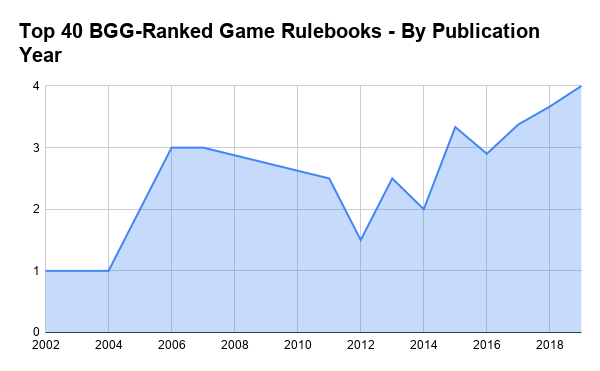

Publication Year

What we found was unsurprising to followers of BGG: the top-ranked games are very much ‘cult of the new’. The rarefied status of the top 40 tended to be newer games. Indeed, 24 of the top 40, or 60 percent of the sample examined, were five years old or newer. You will be able to see a bit later that the quality of the rulebooks in support of gender-inclusive language improves relative to how recently the game was published (see Figure 1). This pool of games are more recently published, and thus, an argument that some of the games were from ’another time’ or an earlier era in which gender-inclusivity was not the norm, would not be valid.

Figure 1

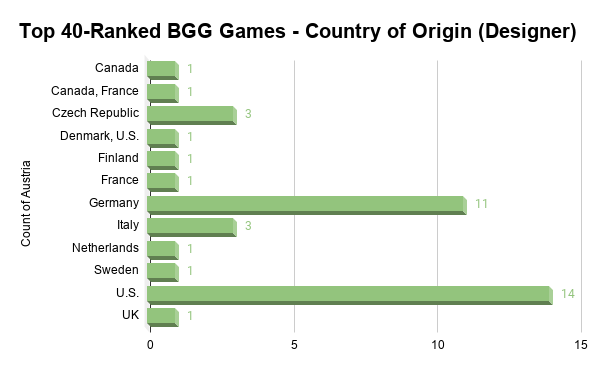

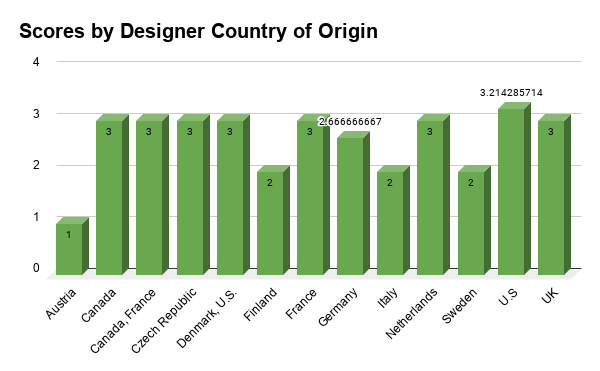

Country of Origin

In this case, we recorded the country of origin of the designer versus the publisher, as many of the games have had multiple publishers over the years. The majority of the games in the sample were designed by people in the U.S. at 35 percent, with Germany coming in second at 28 percent (see Figure 2). This is consistent with analyses of larger sample sizes, a sample of the top BGG sample pulled June 7, 2020 revealed consistent findings with a majority of games designed by either an American or German designer at 223 of the games in the top 400 BGG-ranked games.

Figure 2

Chart

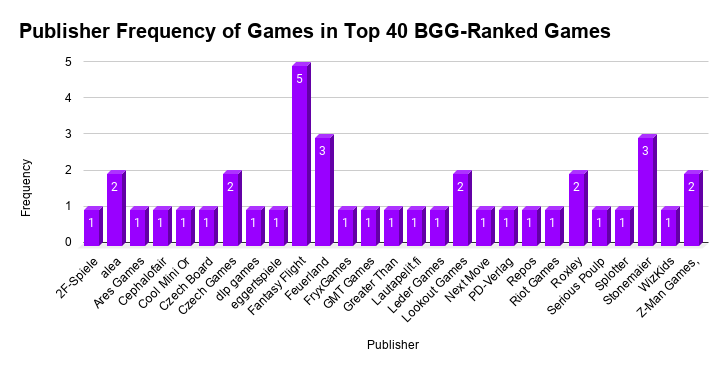

Publisher Frequency in the Top 40

Who were the publishers responsible for these top 40 games? There were 27 publishers represented in the top 40, we also counted how frequently their games were found in the top 40 listing. In this case, we only listed and counted the first publisher listed in the BGG game profile. Fantasy Flight held the top spot with five games in the top 40, with Stonemaier and Feuerland holding the second place at three games apiece (see Figure 3). It is a reasonably diversified list revealing that no one publisher dominates the top-ranked games, and gives us a window into the rulebook writing and design practices of a fairly wide field of designers and publishers.

Figure 3

Chart

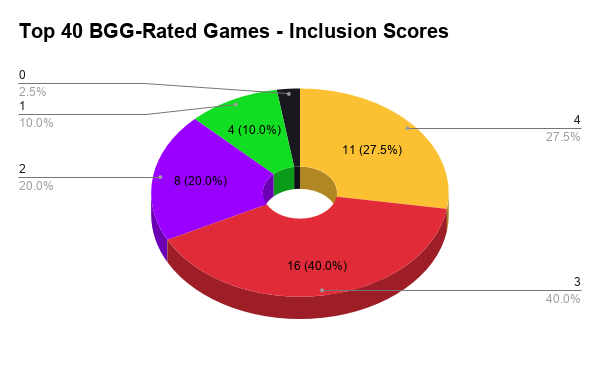

Game Scores

Based on our grading rubric (see Appendix) our 40-game sample had 11 games that got an A+ or a perfect 4/4 score, meaning the rulebook had a good mix of gender representation in language and imagery. There were 16 games scoring 3 at a solid 75 percent. Eight of the games got a 50 percent or 2 out of 4. Finally, 4 games got a 1 out of 4 or 25 percent. Only one game, War of the Ring – Second Edition (2012) scored a zero on gender-inclusive language and imagery in its rulebook. Based on these aggregate scores, this sample scored a 70 percent average among the top 40 BGG–ranked games (see Figure 4). We should look at this number with a disclaimer in mind; we marked this small sample size with a great deal of generosity. Our grading framework is described at length in the Appendix and we’ll reflect on this further in the discussion section.

Figure 4

Scores by Publication Year

As noted earlier, the scores tended to improve as the years wore on, with some peaks and valleys along the way. The games in 2002, scored on average, a 1 out of 4. The game rulebook in 2019 scored a 4 out of 4. The newer the game, generally speaking, the more gender inclusive the rulebooks were observed to be (see Figure 5). Based on the same sample, it would appear that there is incremental, however limited, progress to a more gender-inclusive approach to rulebook writing.

Figure 5

Scores by Designer Country of Origin

Based on the analysis, slightly higher scores on average were found in rulebooks created by U.S. designers. There’s a big caveat here that this finding might not be a meaningful correlation, as without visibility into the processes and practices that support the creation of the rulebooks, it is difficult to know whether it is a meaningful metric at all. It might ultimately be the responsibility of the publisher to create and localize some of these materials so the challenges with the rulebooks, if any, can’t necessarily be rested at the feet of the designer(s). There is also a challenge that we anticipate might have occurred in the English translations of some of the rulebooks. Nonetheless, we are presenting these correlations to demonstrate the score performance against this variable (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

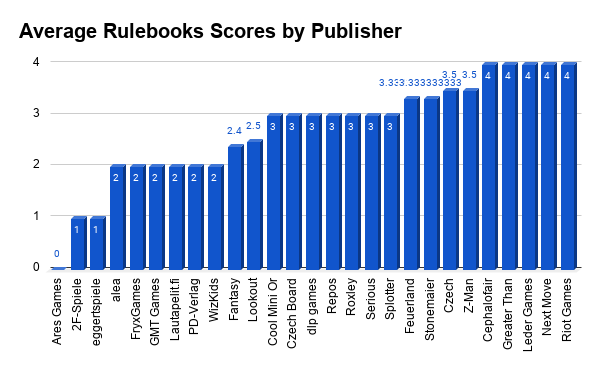

Average Scores by Publisher

How did each of the publishers do in terms of the relative scores? Gloomhaven (2017) publishers Cephalofair, Spirit Island (2017) publisher Greater Than Games, Root’s Leder Games, Azul’s Next Move and Riot Games, publisher of Mechs vs. Minions (2016) all scored 4 out of 4. What did these game rulebooks do well? They all scored at least one point in the 4 rubric categories. For example, Mechs vs. Minions’ rulebook uses the imperative voice, addressing the reader as ‘you’ consistently throughout. While there is a reference to a ‘he’ in the description of a Boss with the line, “Once he takes 1 Damage” on page 2, there was a consistent use of equitable references to masculine and feminine imagery, pronouns and characters. Corki, Heimerdinger and Ziggs are the three male-presenting Yordles; Tristana is the sole feminine-presenting Yordle in the core set. It should be noted that if there were any women/girl playable characters, the rulebook was able to score a point in the category, and there was a line drawing of Tristina on page 9 of the rulebook. Again, if there were any images of feminine-presenting characters, the rulebook scored a point. In the image category, we did not count the number of images to look for equity, nor did we look for a gender balance in terms of playable characters. If looked for parity of images in this sample, the marks overall might not have been as high as these findings currently reflect. In a similar vein, another strong finisher was Root.

Ares Games’ War of the Ring – Second Edition (2012) got the lowest score. Even with our generous marking scheme, this game scored zero in each of the four categories. We noted in our field notes that the subject matter is inundated with masculine representation as the game is very closely based on the Tolkien universe. The rulebook has no feminine imagery, no reference to feminine-presenting characters (which is understandable given the mostly masculine-dominated source materials, though other companies like Fantasy Flight Games have deliberately featured strong feminine-presenting characters such as Galadriel, Éowyn, and Arwen in their Lord of the Rings games), and exclusive reference to ‘he’ in the rulebook. Other games that scored poorly included Great Western Trail (2016) published by eggertspiele, and Twilight Imperium – Fourth Edition (2017) published by Fantasy Flight each scored 1 out of 4, a failing grade. Twilight Imperium – Fourth Edition was completely dominated by masculine imagery, despite having scored one point for some non-male-presenting playable characters depicted on the race cards. Unfortunately, there was a dramatic linguistic imbalance, with the word ‘he’ appearing 224 times and the word ‘she’ zero times.

Great Western Trail was another game that scored a one point as its final score, and it was a bit of a special case. Masculine imagery dominates the rulebook. Indeed, this rulebook really challenged the rubric (see Appendix) and grading criteria. In this case, the imagery is masculine almost entirely based on the game itself. There are images of the 54 worker tiles, 18 tiles of “a cowboy” and “a craftsman.” The cover art features three men: two with moustaches and an older man with a white beard, all of them Caucasian (white) in appearance. The individual meeples for players are called “cattlemen.” The back of the cards echo the front cover of the game with the faces of the three masculine images, and a man sitting atop of a horse and minding three head of cattle. Great Western Trail cannot use the shield of historical realism in this case, as there were indeed 19th-century women cattle drivers. This rulebook appears to overcorrect for dominant maleness of the overall game and uses only ‘she’ in reference to the player. Indeed, the word ‘she’ appears 87 times compared to ‘he’ being used zero times. This observation reminded us of Adrienne Shaw’s (2014) critique that a kind of market-logic pluralism is often offered in place of true representations of diversity. The solution of offering ‘she’ as the only pronoun for the player was, perhaps and we can only speculate, a way of mitigating the exclusion of feminine-presenting NPCs or imagery within the game. As we noted at the time, we couldn’t give Great Western Trail a higher rating than Twilight Imperium – The Fourth Edition as TI was a game that used ‘he’. Given the evaluation criteria of our rubric (see Appendix) both rulebooks lacked a binary gender equality using she and he with relative equality.

Another illustrative example of how we scored each rulebook comes from the middling score we had to give to Viticulture (2015). Its rulebook was inconsistent in terms of gender balance; it used ‘his/her’, ‘he/she’ and singular ‘they’ in places, and then there were other instances of ‘he’ only. The player examples were balanced with ‘she’ and ‘he’ used consistently. The imagery displayed in the game setups and sample cards were gender balanced, with many prominent and positive images of women. We recognize that players are not selecting characters, but rather selecting ‘mamas and papas’. On page 3, we noted the statement: “If a player has a -5 victory point, he may not use a visitor card…” We noted that this phrase was included in a cramped margin around an image and ‘she’ might have been cut for space reasons. On page 6, there is the use of a singular ‘they’ under Spring. … ‘or that player may choose to save their remaining workers…’ and under Spring Actions, “how early that players want his/her work, wake up in the coming year…’ Overall, the rulebook felt like it was written by several writers. This inconsistency prevented this rulebook from scoring a 4 out of 4, instead generating only 3 out of a possible 4. Elizabeth Hargrave’s award-winning game Wingspan also published by Stonemaier, on the other hand, scored a perfect 4 for its consistency. Wingspan uses the imperative or declarative to avoid using gendered pronouns entirely. For example, here’s the imperative at work, “Move your action cube from right to left… and Use 1 of your action cubes to mark your score on the end-of-round goal.” The rulebook issues commands to the would-be player as though the writer and the reader were in conversation.

Another middling score came as a surprise: Mansions of Madness: Second Edition (2016). Designed by Nikki Valens, Mansions of Madness: Second Edition has a game rulebook that we were expecting to have strong gender balance because of the diversity of playable characters and the strong presence of women in the imagery of the rulebook. Unfortunately, we were destined to be wrested out of our assumptions as the descriptions of the player or investigators in this rulebook were referred to as ‘he and him’ throughout. Again, we found this strange as half of the playable investigators are women. There was a good alternating use of player examples using a mix of the women and men investigators. We noted that we were quite surprised to see the player as a default ‘he’ in this particular rulebook given its other gender-inclusive strengths.

Figure 7

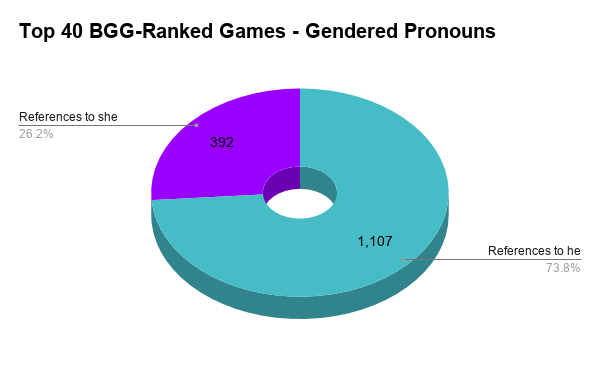

Number of Pronouns

One of the most difficult aspects of these analyses was the manual count of the frequency of the pronouns ‘she’ and ‘he’ in each of the rulebooks. There was no automated way to do an accurate count of the recurrence of these words, she and he, despite our best efforts. Some of the PDFs were not convertible into accurate plain, clean text to process through text analysis tools. What we had to do instead was literally count them manually in each case. The search for ‘he’ returned a bunch of false positives in any search tool we used, finding instead, for example, the ‘h’ and ‘e’ in words like ‘the’. It was a process of painstaking search and exclusion. Based on this count, the word ‘she’ appears 392 times or 26.2 percent of the total, and the word ‘he’ appears 1,107 times or 73.8 percent of time in the rulebooks of the top 40 BGG-ranked games. You are 2.8 times more likely to see a reference to ‘he’ in this sample of rulebooks than to see a reference to ‘she’ (see Figure 8). Phrased another way, for each “she” there were nearly three “he” pronouns in these rulebooks.

Figure 8

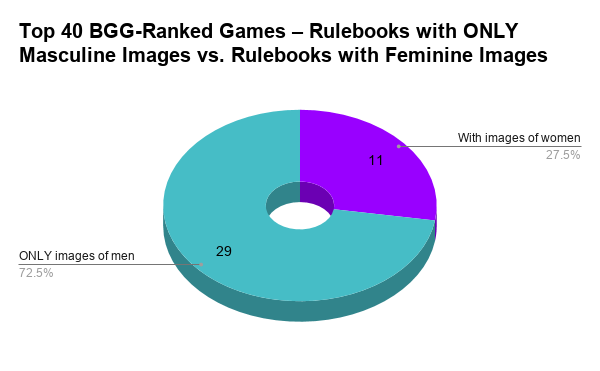

Images in Rulebooks

A similar split was found in analysis of masculine versus non-masculine imagery in the rulebooks. Only 11 rulebooks or 27.5 percent of the sample contained even a few images of feminine-presenting representation in their pages. We were quite lenient in this category, as earlier noted, and gave the rulebook a point if there was even one image in the rulebook that was feminine-presenting. In our analysis, we found only the gender-neutral spirits in Spirit Island as possible non-binary figures, and in this case—the game also had represented feminine–presenting characters as well. In this case, 72.5 percent or 27 games had absolutely no images of women or girls (Figure 9)

Figure 9

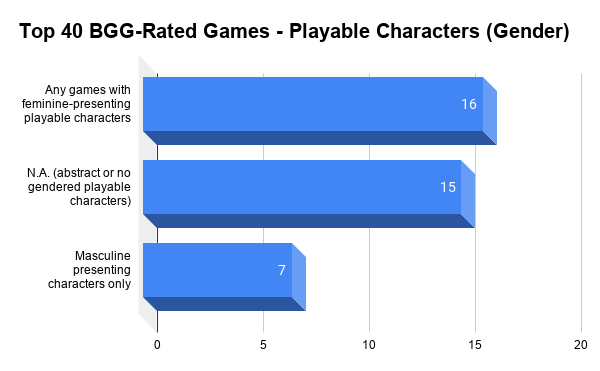

Playable Characters

One key variable which we determined is a key broader indicator of gender inclusion in board games was playable characters. We found that 42.1 percent of the games or 16 of the top-ranked BGG games had the option of at least one playable character who was a woman or girl; this represented 63 feminine-presenting playable characters across 16 games (see Figure 10). One has the choice of only masculine-presenting playable characters in 7 of the games or 18.4 percent, and 15 games were abstract or had no assigned playable characters (i.e. one can play as themselves or create their own character).

Figure 10

Game Designer Diversity

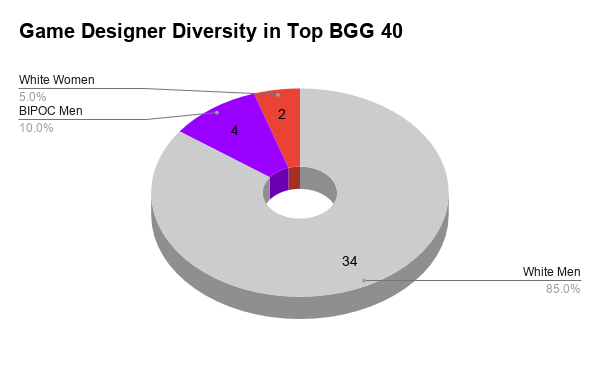

Of the 40 games analyzed, 34 were designed by white men, representing 85 percent of the games analyzed. BIPOC men designed four games in the top 40 or 10 percent of the games analyzed. Eric M. Lang is the designer of Blood Rage (2015), Ananda Gupta is the co-designer of Twilight Struggle (2005), Jonathan Ying is a co-designer on Star Wars: Imperial Assault (2014), and Prashant Saraswat was a co-designer on Mechs vs. Minions (2016). Two women designed games in the top 40, representing five percent of the analyzed sample. Nikki Valens is the designer of Mansions of Madness: Second Edition (2016) and Elizabeth Hargrave is the designer of Wingspan (2019) (see Figure 11).

Figure 11

Rulebook Inclusion Scores for Games with Diverse Design Teams

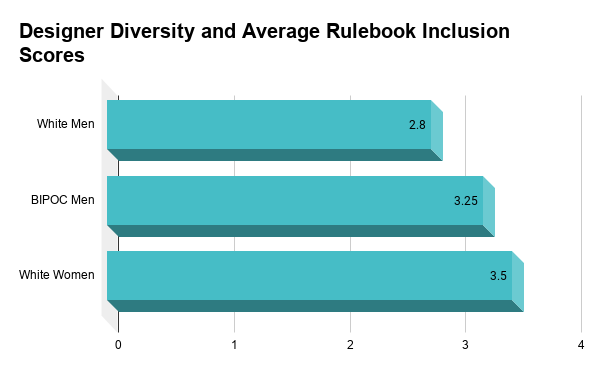

Does a more diverse team create more inclusive and representative content? We noted disparities in the publisher findings with wild swings as seen in Fantasy Flight Games which recorded scores for their games that ranged from 1 out of 4, to several 2s out of 4, to 3, and finally, a 4 out of 4 perfect score. These swings generated an average score of 2.4 for Fantasy Flight Games. This finding indicated something, potentially, about publisher workflows. We wondered whether, perhaps, the designer and/or design team might be a key factor in how the rulebook was crafted and executed. In this limited sample, we did find a correlation between the diversity of the design teams and the inclusivity of the rulebooks. In this case, games designed by women, Hargrave and Valens, scored 3.5 out of 4; games designed by BIPOC men scored an average of 3.25 out of 4; and games designed solely by white men scored an average of 2.8 out of 4. This finding was interesting, but which would need significantly more research to determine if a correlation can be further verified through analysis of a larger sample (see Figure 12).

Figure 12

Chart

Building a Better (Or, At Least, More Inclusive) Rulebook

Given these findings, what have we learned? It is a common argument amongst amateur grammarians that masculine pronouns are meant to represent the human default. Although it is often argued that masculine pronouns are the genderless pronoun, the default, generic pronoun that can refer to all individuals, in practice the masculine pronoun holds masculine connotations. English professor and creator of the Pick Up and Deliver podcast Brendan Riley shared his own experience with this approach as a young reader of Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, a science fiction book about an envoy sent to live among a race of ambisexual people on the planet Gethen. The race could select their preferred gender identity and sexual organs when they became fertile. Riley noted his printing of the book used the pronoun ‘he’ and ‘his’ to represent the sexless race while other printings approached the citizens of Gethen differently. Riley noted that he did not read the “neutral” use of he or his as without gender, instead he imagined all Gethen denizens, in his mind’s eye, as men.Riley’s story underlines that masculine pronouns aren’t read as universally inclusive of all gender identities by some readers. Indeed, in his study of generic pronouns and sexist language, Gastil found that students, regardless of their gender, created significantly more mental images of men than women when presented with the generic he, concluding that this pronoun contains a male bias. Moreover, in her discussion of the history of pronouns, philosopher Amia Srinivasan describes the generic he as “a tool of the patriarchy,” explaining how this pronoun has historically been used to legally exclude women. With these arguments in mind, rulebook writers, all writers, should be mindful of how their choice of language lands with audiences, and what their choices do to their readers.

There are a number of approaches and ways to ensure linguistic inclusion in a rulebook. We itemize three simple options below: second person (you), the inclusive-binary (s/he), and the singular they. While this is by no means a complete list, this provides game designers and publishers with a few tools in their tool box with which to tackle the question of inclusion:

Hey YOU, yes, YOU. There are many approaches to rules writing that can be taken that don’t rely on the masculine pronoun. Board game commentator, and rulebook writer, Kevin Carmichael of Dancing Giant Games, noted that it was imperative to make a games rulebook sound like a conversation with the game player. Liberal use of ‘you’ and ‘your’, the use of the declarative or the imperative, can help would-be players learn more quickly and easily, allowing rulebook writers to avoid the use of gendered pronouns entirely. This approach has been used in technical communications for centuries and has the advantage of treating any reader equitably regardless of their gender. In her study of 19th century sewing machine manuals, Katherine Durack analyzed pre-Civil War leaflets that were exemplary models of “gender neutral technical communication: writing that employs surface-level features that are not marked for gender (such as a preference for sewing machine operator over seamstress.” By using an impersonal tone, imperative voice, and non-gender-marked pronouns (“you”), these instruction manuals avoided explicitly gendering or assuming the gender of the reader.

He or she, she or he. Another alternative approach could be the use of “she/he” or “ she or he” or s/he to provide further equality within a rulebook. This methodology, however, comes with its own issues and restrictions. Firstly, “he or she” as is often used positions men first, linguistically and symbolically signaling their importance and value over women. This male-first approach is common, according to Lee and Collins, who discovered male firstness was twelve times more common in Hong Kong textbooks than female firstness. While the linguistic strategy of feminization does increase the visibility of women, the use of “she or he” is reductive, suggesting only a binary understanding of gender (i.e. that if one is not a “he” they must be a “she” and vice versa). Because this approach could be more inclusive, as it ignores the very existence of people with gender identities that are non-binary, “she or he” is not an ideal solution either. Further, additional studies have suggested that “he or she” invoke different mental images for readers based on their own gender (e.g. women produce mostly mixed or female-presenting images while men imagine male-presenting images almost exclusively). This approach, then, does not eliminate the gender bias for either gender and is not an ideal solution for creating gender neutrality within a text. Further, this gender–binary approach does not embrace the complexity, diversity and reality of gender expression.

Singular they. Then there is the use of the singular they. Merriam-Webster Dictionary has definitively helped us to settle the debate about its use. The dictionary announced in September 2019 that ‘they’ was now to be embraced by grammar snobs and casual texters alike as a singular pronoun. This decision was more of a re-certification or stamp of re-approval however. As argued by Darr and Kibbey, “the two major advantages of singular ‘they’ are neutrality and naturalness” (80), noting that the singular “they” has been in existence for several hundred years. Indeed, it was in common use in the 1300s in English literature. Often used today when the gender of someone is unknown, the singular “they” is a neutralization strategy that has become increasingly accepted. Singular they “can also be used to transcend the binary gender of he/she and hereby refer to an individual with a non-binary gender identity” (Lindqvist 111), providing further representation and inclusion within a text. In studies that examine the use of the singular “they,” however, it was revealed that even this generic pronoun tends to include an inherent male bias. In their analysis, Merrit and Kok argued that, while less biased than the generic “he”, the singular “they” still trended towards a male bias. Gastil similarly found that, when subjects were confronted with the generic pronoun, they created a more even distribution of feminine and masculine images. In particular, the singular “they,” compared to “he/she,” was the pronoun that gave “women the greatest opportunity to see themselves.” These study findings corroborate a previous study from Bem and Bem, who, as early as 1973, indicated that when presented with gender-neutral language in a job posting, women were more motivated to apply for that position. Gender-neutral language, then, allows for women and non-binary people to see themselves in a text without negatively affecting cisgender men’s understanding of a text.

Discussion

These analyses reveal something interesting about board gaming as a sector and a cultural pursuit. It can be argued that this top 40 sample represents what might be considered the cream of the crop of the tabletop hobby. At the time that this sample had been extracted from the BGG database, 1 million users had ranked these games as the best 40 games in the hobby. Yet, this cream of the crop could only manage 70 percent average in terms of gender inclusion based on the criteria outlined in the Appendix. How gender inclusive are the rulebooks found in the top 40 BGG-ranked games? There was a significant imbalance observed in the use of gendered pronouns as outlined Figure 8. The word ‘he’ was used nearly 3 times more frequently than the word ‘she’. The vast majority of the rulebooks at 72.5 percent featured absolutely no images of women and/or girls as outlined in Figure 9. Given the limited sample size of this study, we can only speculate whether game rulebooks further down on the BGG database would have more or less gender inclusion. That’s a bigger study for another time. What do the findings in this limited sample tell us? There’s an observable imbalance. There’s more work to be done.

It must, at this point, be noted again that we applied the rubric (see Appendix) very generously. If there were any, even one, female-presenting playable characters, the rulebook scored a point. If there were any women or girls depicted, that qualified the rulebook for a point. An example of this generosity in play was the grading of Food Chain Magnate. In this rulebook, there was a very gendered description of roles within a restaurant chain. For example the CEO is referred to as a man (e.g. “The CEO can have up to three cards reporting to him…”), the regional manager is male-presenting and there is a reference to an ‘errand boy’. There are cards called waitresses and there is a bonus for ‘First waitress played.” There is a reference in the flavor text at the beginning which reads, “And fire that discount manager, she is only costing me money.” This particular ‘she’ represents one of the two references to ’she‘ in the rulebook. We gave this rulebook a point for women non-playable characters, despite the argument that might be made that the representation is not necessarily positive. As this example illustrates, if there were any images of women or girls, even if this reference was arguably negative, then the rulebook scored a point. The only area where we were looking for strict quantitative parity was the number of references to ‘she’ and ‘he’. If there was an imbalance, significantly more references to ‘she’ than ‘he’, or vice versa, the rulebook did not score a point. If there was a slight difference relative to the overall numbers, as was the case in Arkham Horror: The Card Game (2016) we gave the game a point because the overall thrust of the rulebook was gender inclusive and the gap between references to ‘she’ and ‘he’ was relatively small. In many cases, it wasn’t at all a close call. We are certain there will be those who will criticize this approach, saying that the bar should be held up higher, and still others who will find our approach too punishing.

So what do these findings mean? Through improved representation and steps toward inclusion, is there a chance that more people might be lured into board gaming? A pre-pandemic market study published in February 2020 predicted that the board game market had the potential to grow $5.81 billion during 2020-2024 with a projected year-over-year growth rate of 25.1 per cent. The total overall market was forecast to reach $12-billion (U.S.) by 2023. It is hard to project where the board game industry will land during this time of global economic upheaval, and global supply chain interruptions, but it isn’t hard to imagine continued interest in board games during a time of self–isolation and families in lockdown or quarantine. There are some fascinating analyses of board games growth during the Great Depression, including a story about Scrabble creator Alfred Mosher Butts, an architect who turned his prolonged unemployment and penchant for linguistic analysis into his creation of the board game classic. While the future of the industry (or any industry for that matter) isn’t clear, what is clear is the audience for board games has continued to grow, and there is some evidence that the pandemic has increased demand for this home-based activity.

The growth potential is clearly there. Can the hobby do better? During times such as these, it is hard to be an optimist but, in this case, we believe that the industry, and a growing list of increasingly diverse board game creators can make things more inclusive, and collectively, make things better. Further considering the findings of this study, we recall a story about Van Halen’s infamous request that all the brown M&M’s be removed from their pre- and post-show catering order as part of their rider. This story was passed around urban-myth style for years, with some people shaking their heads at this celebrity entitlement run amok. Yet Van Halen had a solid reason for this odd stipulation. In an interview, erstwhile front man David Lee Roth said that if they discovered brown M&M’s on their craft services table backstage, the band knew the venue wasn’t looking closely at the full contract. The contract and the venue’s ability to handle things, big and small, mattered. That’s because Van Halen had a stage set up that included massive 850 par lamp lights, a rig that could have life or death consequences if not installed correctly. If the venue wasn’t getting the brown M&M’s right, the small details and courtesies, the venue likely wasn’t getting the big things right either. Rulebooks are, perhaps, the brown M&M’s, the small courtesies that signal a larger commitment to inclusion. Recalling Yucel’s piece on rulebooks and their importance, there are some that might suggest that rulebooks might even be the rigging of the 850 par lamp lights, a more fundamental, and mission-critical commitment to a diverse and growing audience for board games – a foundational commitment to welcoming players into the game. Either way, publishers and designers need to get the big and small courtesies right. These things send a signal of inclusion to the wider market, and to publics looking for a way into the increasingly vibrant and dynamic board gaming community.

Conclusions

We can’t imagine why one wouldn’t want more people playing board games, excited by board games, invited by board game makers rather than less. At its best, board gaming is all about invitation, sharing, and community. As players and fellow members of the community, if we knew that something we were doing was creating a less welcoming space, we’d want to know, we would want to correct the misstep, we’d want a chance to try again, and do better. This is the spirit of continuous improvement; this is innovation. The desire to learn, grow, innovate and include is what creates, and maintains, a community. It what creates a viable, vibrant industry. Sometimes, hearing that you aren’t doing as much as you can, that you’ve got more work to do, this can be frustrating and overwhelming. However, it is in these moments of tension when the solutions come, when we can improve our societies, and ourselves. It is in the tiny courtesies, the small gifts we give each other, the millions of acts of reciprocity and kindness that foster nurturing relationships and healthy neighborhoods, workplaces, organizations and cultures.

We think this sector and hobby is one of the richest, most compelling areas of study we’ve ever encountered. We think some of the board games we’ve looked at in this sample are works of art, even the ones with rulebooks that didn’t get a passing grade. We believe board gaming is an important business sector, and a rich and fruitful cultural endeavor. Board games are critically important as tools for learning, connecting socially, thinking strategically, critically, and systemically. We believe that board games can change the world for the better. Board games can be for everyone. Some progress is being made, albeit slowly, in a stutter-step, one-step-forward-two-steps-back sort of way. There are some positive discussions happening in the industry about equity, diversity and inclusion. There are renewed discussions about the need to hire diverse teams. There are initiatives to help the games made by women, non-binary, LGBTQ2AI+ and BIPOC game designers to get published and promoted. We’d add that publishers should look to paying women, non-binary LGBTQ2AI+ and BIPOC people (well!) to review games to determine how designs, themes, stories and rulebooks land with audiences. Through listening, doing some perspective taking, having some empathy, we can all do what it takes to help bring about positive changes in the hobby and industry we love. A small step in the right direction?: to paraphrase podcaster Riley, publishers and game designers might make more effective use of language to welcome audiences. Finally, as members of a fandom, we all know that analytical pursuits such as a nit-picking analysis is an act of love. Any human endeavor benefits from taking a critical eye, quantifying variables and asking: could this be made even better? This study provides a look at some of the numbers. The question, ”can we make more gender-inclusive rulebooks?” is now left for the industry to tackle. As with previous pursuits, our goal is to provide just the data, a trendline and a pattern, because as the old Drucker quotation says, “What gets measured gets managed.”

Appendix

Data Collection

To answer our research question, “How gender inclusive are the rulebooks found in the top 40 BGG-ranked games?” we first extracted the top 40 BGG-ranked games on Dec. 23, 2019. The BGG list is always in flux, so it needs to be said that our data sample is a snapshot in time. Then, working from that December 23, 2019 list, we downloaded the full PDF manual of each of the games from online sources such as (mainly) BGG, publisher’s websites and in some cases, F.G. Bradley’s retail site. What has been excluded from the list of 40 top games is Kingdom Death: Monster (2015) because we couldn’t find the full rulebook during the time of our analyses. Glimpses of solitary images from the rulebook online and reviews on sites like Shut Up and Sit Down confirmed that there were plenty of women depicted therein, often in various states of undress. We can’t weigh in further and thus, this rulebook was not analyzed. Instead, we expanded the list to include Azul (2017) in the 41st spot to round out the top 40. In every case, we looked strictly at the core rulebook rather than the quick-start guides or how-to-play manuals, when there were a range of documents to select from. We read each of the manuals page by page, collecting field notes in a notebook with our observations. We used a binary signifier for each of our coding criteria 0 for absent and 1 for present in each of my final coding criteria. These criteria included whether the following groups of criteria were present or absent:

Category 1 for 1 point

-

- Non-male-presenting playable characters

-

- Non-male-presenting NPCs/non-masculine images within the game

-

- Players could select their own gender identity

- The number of playable non-male-presenting character

Category 2 for 1 point

-

- ‘She’ only was used in reference to players within the rulebook

-

- ‘He’ only was used

-

- ‘He or she’ was used

-

- S/he was the variant used

-

- They (singular) was used

- No gendered pronouns (player or you) were used

Category 3 for 1 point

-

- Any presence of feminine-presenting imagery/references

-

- Player examples demonstrated gender balance (or roughly equal numbers of masculine and feminine examples such as Susan and Bob)

- No reference to gender was used at all

In the final category, we also logged information on the following variables. This was the only category where we did a rigorous, manual, and assuredly painstaking count.

Category 4 for 1 point

-

- Number of pages in the rulebook

-

- The total number of ‘he’s’ used in the manual

-

- Number of she’s

- Number of they’s (in this case, we tabulated any instance of the word ‘they’ and not simply ‘they’ used as a singular pronoun

These above elements were collected alongside the game’s Geek rating, the average user rating, the number of voters, designer’s name, the designers country of origin, the publication year of the game, the weight of the game as ranked by users, the game theme and category, as well as the edition or year of issue of the rulebook. All of this information was collected manually and recorded in a spreadsheet. There were a wide number of variables to collect and, in order to determine the relative gender inclusivity, we created a rubric that graded each rulebook out of four points (see Rubric Table). The top-most ranking, a 4/4 finding, reflects a consistent, diligent effort to ensure gender inclusivity throughout the manual containing at least 4 of 4 aspects of inclusivity including playable and/or non-playable characters that are male-presenting/female-presenting, that those characters depicted in a relatively balanced way in the rulebook, that there is a the use of singular they, or he or she, or s/he, and there is a consistent representation of gendered player examples and/or imagery in the rulebook that is relatively gender balanced. A word on qualitative analysis here before we continue. Qualitative analysis by its nature involves some subjective assessment, as Tanya worked through the grading, as anyone who has ever had to grade a paper or review a board game knows, there are times when you have to make a judgement call. As she graded, Tanya contemplated the intention and the context of the wider rulebooks.

Rubric Table

Rulebook Gender Inclusion Rubric – Ranked out of 4

| 4 | Excellent

|

| 3 | Good

|

| 2 | Limited

|

| 1 | Poor

|

- Pobuda, (2020). Gender Inclusivity in Board Game Rulebooks: Grading Rubric. Original Table

About the Authors

Tanya Pobuda studies board games, communication, serious games and simulation in higher education, training and communication at the Ryerson University and York University Communication and Culture Doctoral Program. She holds a Master’s of Professional Communication (MPC) at Ryerson University and has a Bachelor’s of Journalism, High Honours from Carleton University. Ms. Pobuda has had a 24-year professional career in marketing and communications, beginning her career as Toronto-based technology journalist and news editor. A licensed drone pilot, artificial intelligence practitioner and board games scholar, she lives in a home with thousands of tabletop and video games. She can be found on BoardGameGeek at TPOE or at her projects website https://tanyapobudaphd.com/ She is a member of the AGS Editorial Board.

Shelly Jones is an Associate Professor of English at SUNY Delhi, where she teaches classes in mythology, folk lore, literature, and writing. She received her PhD in Comparative Literature from SUNY Binghamton. Her research examines analog, digital, and role-playing games through the lens of intersectional feminism and disability studies. She is a member of the AGS Editorial Board.

Acknowledgments

We greatly benefited from the peer review process. Every effort was made by Tanya to ensure the accuracy of her data. The responsibility for any errors in the resulting work remains entirely that of Tanya Pobuda, and she is committed to continuing to refine and expand upon her data set. Thanks to Derek Schraner for his prodigious board game knowledge, board game collection, and his fierce commitment to the Oxford comma.