Miniatures wargaming is underrepresented within game studies, lacking a settled, cohesive definition. My goal is to start the process of defining miniatures wargame rather than providing the final word. As such, I suspect that other scholars will iterate upon this document, and I welcome that ongoing scholarly conversation. Below I present five theses, derived from autoethnographic and ethnographic methods. In addition to being a lifelong miniatures wargamer, I conducted a qualitative study of miniatures production in Nottingham to assess workers’ motivations for choosing the form as both hobby and work. I locate five primary pillars which define miniatures wargaming as a form. These are the singular importance of the table, the use of non-discrete movement, the order of operations in play, the use of bricolage, and the centrality of production.

I rely heavily on the work of Meriläinen, Stenros, and Heljakka for the theoretical scaffolding of this article.1 In particular, I adopt their naming conventions for the larger hobby within which miniatures wargaming is located. “Miniaturing” is theirs, referring to the meta-hobby of using miniatures. The term “miniaturist” is my own, derives from their work, and refers to those engaged in miniaturing.

Miniatures wargaming is a type of analog game in which two or more players recreate battles of various scales through the use of miniatures and, for the most part, three-dimensional terrain. Each miniature is a representation of an individual person or, rarely, unit on the battlefield. One of the few definitions of miniatures comes from games studies scholars Meriläinen, et al., who define them as “scaled-down metal or plastic representations of historical and fictional characters, creatures and objects, typically used for gaming and display purposes.”2 Participants assemble and usually paint miniatures prior to play, and miniatures range from fidelitous recreations of historical soldiers to sci-fi Space Marines3 to fantasy elves or orcs. There are hundreds of such games, depicting a range of historical periods and literary genres. The presence of the miniature and terrain are necessary components of miniatures wargaming. The more general term “wargame” also includes two-dimensional analog games such as Panzer Leader by Avalon Hill. Those games are more akin to complicated boardgames such as Stratego, and most often use cardboard “chits” as playing pieces.

Analog Taxonomies

There are multiple types of analog game, each with their own specific practices, including: boardgames (which includes board-based wargames of the old Avalon Hill style), card games (which includes games like Magic: The Gathering as well as older games like poker), tabletop role-playing games or TTRPGs (such as Dungeons & Dragons), and miniatures wargames. Of these, the miniatures wargame has received the least attention in game studies literature.

The contours of the miniatures wargames industry closely mirror those of the role-playing game industry. Within that industry, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) has become so dominant that the brand name is synonymous with role-playing as an activity. D&D, along with Magic: The Gathering, keeps Hasbro profitable.4 A singular publisher also dominates the miniatures wargames industry. There, the dominant company is Games Workshop, producer of the Warhammer series (this includes Warhammer Fantasy Battles, Warhammer: Age of Sigmar, and Warhammer 40,000, henceforth referenced as WFB, AoS, and 40k, respectively). Games Workshop is at least as dominant in miniatures wargames as WotC is in tabletop role-playing and card games, and nearly as profitable, with revenue in 2022 of £385 million.5 Further, Games Workshop is a comparatively healthier company than WotC parent company Hasbro; it is regularly one of the top performing stocks on the London Stock Exchange.6

That miniatures wargaming has received less attention than other analog games is surprising, not only because of Games Workshop’s financial success, but because histories of modern games, whether digital or analog, find their common starting point in the miniatures wargame. Miniaturists often consider Little Wars by H.G. Wells the precursor to modern miniatures wargaming.7 While drawing from the older wargame Kriegsspiel, which uses wooden blocks to represent soldiers, Little Wars popularized the usage of miniatures in wargames. It was also one of the first wargames of any type made for a popular audience. Little Wars served as inspiration for the creation and design of D&D, as creator Gary Gygax has noted.8 In turn, D&D served as the model for computer games such as the Ultima series and World of Warcraft. A chain of influence stretches from the first military wargames through modern tabletop role-playing games to today’s technologically sophisticated digital games.9

Miniaturing as a Practical Framework

Today, miniatures wargaming constitutes a distinct mode of play and craft. This section describes miniatures wargaming in a formal sense. Much of the history of miniatures wargaming is left to a network of non-academic blogs, forum posts, and popular press works. These are quite useful. Zhu Bajiee’s examination of early Warhammer’s left-wing satirical history is exhaustive in its analysis.10 Nonetheless, there is often confusion around what miniatures wargaming is. Mikko Meriläinen, Jaakko Stenros, and Katriina Haljakka offer the most comprehensive analysis, based on a qualitative survey of the practices and attitudes of Finnish wargamers.11 They posit that miniatures wargamers do more than just play, paint, or imagine. They engage in a complex assemblage of interlinking and overlapping practices, which they call, simply, miniaturing.

The “pastime” of miniaturing, according to Meriläinen, et al, include practices of crafting, gaming, storytelling, collecting, socializing, and displaying/appreciating. Miniaturists engage with these practices to varying degrees. Some do all of them, others practice one to the exclusion of others. Tournament players provide an example of the latter. Tournament players “chase the meta” (i.e. pursuing maximum efficiency and competitiveness) of a given miniatures wargame by cycling through armies in the hopes of building the most powerful force for competitive play. They frequently hire others to assemble and paint their armies, are uninterested in storytelling, and collect only temporarily before selling and moving on to the next army as the metagame shifts. This situation around tournament play creates a small but vibrant economy of professional painters, such as at White Metal Games in Raleigh, NC, who eke out a living by doing the craftwork which tournament players eschew.

Meriläinen, et al. make special note that, of these practices, crafting and gaming constitute the “dual core” of miniaturing.12 These two practices are most prominent in their survey responses and serve as a precondition of sorts to the others: miniatures are bought unassembled and unpainted, necessitating at the very least some amount of assembly and the social expectation that they be painted (even if someone else does this work), while playing games with miniatures is the presumptive primary activity for which they are used.

The fully-assembled and painted miniature is a small statue, most commonly between 28-32mm. It does not start out as a statue but as of a set of disconnected parts on a frame (in this case plastic13), called a “sprue.” The sprue is an artifact of the miniatures production process; whether through injection molding in plastic miniatures or a process called “casting” in metal miniatures, sprues provide stability to the shipped product, lowering shipping costs by decreasing their physical footprint and weight, and as a means by which workers remove miniatures from their molds.

Individual sculptors create miniatures in artisanal fashion. They are sculpted by hand, in clay or epoxy, or with digital sculpting computer-aided design (CAD) software. When the individual statue is complete, it is broken down into multiple parts for mass production and shipping. At this stage, it ceases to be a statue. The miniatures are mass produced by the hundreds or thousands for shipping to hobby stores. There, miniaturists buy them before assembling and painting them. Every miniaturist crafts, if only by putting the miniature together. Not everyone paints, even though the community prefers that miniatures be painted. Those who do usually paint to what is colloquially called “tabletop standard,” a barebones approach which ignores rigorous shading and highlighting in favor of block colors. Others paint their miniatures in lavish fashion for display in their homes or on the internet. While craft remains core to the miniaturing pastime that Meriläinen, et al. describe, there is a spectrum of intensity to the individualized practices that reflects the diversity of commitments within and across miniaturing communities.

Art blogger Patrick Stuart argues that miniatures are the most popular statues in history and the first that people have regularly painted since Ancient Greece.14 He attends to how people use miniatures, emphasizing the importance of gaming in miniaturing even for those who do not game with them: they are designed as they are because they are meant to be played with. According to Stuart, the ubiquitous Space Marines of Warhammer 40,000, with their large, rounded shoulders and menacing poses, look the way they do “because the player is always looking down on them from above — and they need to pop against a mixed background.” Put another way, even the miniaturist least invested in gaming assesses a miniature in its capacity as a game piece, not in spite of it.

From Miniaturing to Miniatures Wargaming

Meriläinen, et al. stress that “Miniaturing is a particularly material pastime.”15 This phrasing contains within it two demands. One, the observer must note the particularities of miniaturing, which carry over to the broader milieu within which miniaturing exists, i.e., the game, and even more specifically, for my purposes, the miniatures wargame. Two, all games are material,16but miniaturing and its associated games have an especially intense focus on the material. As Meriläinen, et al. note, “The pastime features a constant interplay of the material and the immaterial: the miniature serves as a focus for activities, and the activities contextualize the miniature.”17 This is not merely an intellectual exercise. Games Workshop considers Warhammer intensely material. One of the differences between Games Workshop and WotC is that the former insists that there will never be a 1:1 translation of Warhammer to the digital. There are video games based on Warhammer, but no exact digital copy of the tabletop game.

While Meriläinen, et al.’s analysis is rigorous and foundational, it is not exhaustive: while they do a thorough job of theorizing the miniaturing pastime, they provide no definition of what a miniatures wargame is. Their interest lies in the use of miniatures in a variety of analog games, rather than in wargames, specifically. For instance, players expected the presence of miniatures in early D&D play, though such miniatures were not required and were used in smaller quantities than in miniatures wargames. Some boardgames, such as Gloomhaven and Descent, also use miniatures. Miniaturing practices, expectations, and norms differ across the various analog games where they are used or present. Meriläinen, et al. note that miniaturing as a pastime contains within it “a number of contentious areas.”18 As a lifelong analog gamer, for instance, I have observed that the social expectation that miniatures be painted is more intense within miniatures wargaming circles than other analog games communities.

The use or presence of miniatures alone is not what makes a miniatures wargame a miniatures wargame, even as it is true that the use of miniatures is the basic precondition for a miniatures wargame to exist. With Meriläinen et al.’s exhortation to pay attention to the particulars and materiality of miniaturing and, thus, miniatures wargames, in mind, I return to what I consider to be the main elements to a miniatures wargame: the centrality of the table to gaming, the use of non-discrete movement, a particular order of operations in play, the use of bricolage to populate the game space, and the centralized production of miniatures wargames. My elaborations upon each of these, in turn, are informed by my status as a longtime miniaturist and as acafan.19 I am both participant and observer, and my definition builds on my knowledge of and experience within miniaturing.

1) The Centrality of the Table

The centrality of the table is the distinguishing aspect of miniatures wargaming, even more so than the presence of miniatures. The table’s notability here seems odd. After all, aren’t all analog games played on tables of some sort or another? The answer is yes, but nowhere else does the table organize proceedings to the extent that it does in miniatures wargames. Space is a major consideration. Miniatures wargames require a larger spatial footprint than other analog games. The traditional size of a miniatures wargame has remained remarkably uniform for most of the form’s history at 6’x4’. When WFB launched its third edition, in 1987, the recommended table size was 8’x 4’ but Games Workshop quickly adjusted to the more standard 6’x 4’. Taking cues from the industry leader, these dimensions were de rigeur until recently.20 Compared with other analog games, these spatial requirements are enormous. A standard home has room for only one table, while even large stores and gaming clubs are limited in the number of tables they can provide.

The standardized table dimensions are important due to the use of measurement and perceptual grids rather than the designer demarcated grids that one sees in boardgames. This mode of gaming, in which players measure in inches and may move their miniatures in any direction, creates a form which is hungry for space. That hunger for space creates something of a tautology within the miniaturing culture: I need more space to fill with miniatures and I fill it with miniatures because I have more space.21

A boardgame or card game takes place on a table, but its dimensions are set to something smaller than the entirety of a table—you play Settlers of Catan on a portion of your kitchen table, leaving space between the various boards and cards for drinks or snacks. Miniatures wargaming takes place over the entirety of the table, which miniatures wargamers consider a sacrosanct place. They do not place drinks on it, and they never roll dice too close to the miniatures for fear of knocking them over. While Johan Huizinga’s notion of the magic circle has fallen out of fashion in game studies because it tends towards a transhistorical definition of play, it is useful here: the miniatures wargaming table creates a conceptual barrier to certain modes of engagement relating to the table and what is upon it.22 Nicholas Taylor cautions against reading the magic circle as truly magical despite the enduring allure of escape from “everyday cares”: the magic is underpinned by a host of material conditions related to gender, race, and class.23 The widespread no drinks on the table rule illustrates miniatures wargaming’s allure as a means to withdraw from and refuse feminized domestic labor.

The table is ordinarily beneath notice, both figuratively and literally. The gamer pays attention to what is upon the table (the miniatures, the terrain) but rarely thinks of the table explicitly. It is always, however, at the back of their mind as a physical presence which makes the game possible. The miniatures wargamer might have a dedicated space for playing—a “man-cave” (and it is almost always a man-cave, given the overwhelmingly male demographic of the miniaturist)—defined specifically by the presence of the table. The table is always near at hand linguistically and socially: in miniatures wargaming parlance, to remove all of an opponent’s pieces from the table is to table an opponent, a verb-form acknowledgement that the table is an active participant. To have the same done to you is to be “tabled”.

Jason Edwards, via Henri Lefebvre, notes that ‘Space… does not denote an empty void or the given physical environment in which human beings live. Space is rather the social space produced by the material practices of human beings.”24The miniatures wargaming table reconfigures space in its immediate location. A table becomes a social relation rather than a thing. As a personal example, most of my miniatures wargaming takes place in my brother’s gaming room in Greensboro, NC. We withdraw upstairs and sequester ourselves away from the rest of the house by playing games for hours. Dominating the room is the miniatures wargaming table, a fact which denotes the space for miniaturing. The gaming room is a space for playing games, which are themselves a particular set of social arrangements shaped by the presence of a dedicated wargaming table. When we are there, we play. When we eat, we go to the dining room. When it is time to talk about politics, philosophy, or work, we go to the porch.

Not everyone has the free space or money to commit to such a configuration. A friend and colleague plays 40k with his daughter on his dining room table. For the duration of their games, the dining room table is not, in any important sense, a dining room table. The social function of the entire room changes from a domestic space to a play space. When the game ends, the social function of the room shifts once again. Physically, the table is the same object. It is our relation to it which changes and, in so doing, it changes us. However we use it in any given moment, the table is integral to our configuration of sociality around and upon it, where (at the appropriate time) a game’s rules both adhere to and help to determine certain social conventions related to its presence.25

The shifting yet always central role of the table to the miniatures wargame is not limited to domestic spaces. In the North American context, games most often take place in hobby stores, while in the UK they occur in miniatures wargaming clubs. These clubs are organized along the lines of other civic clubs, with dues and elections. The club model creates a different set of social expectations than in the commercially oriented hobby stores. Both have large wargaming tables, but the sociality around them changes: the hobby store prominently places paints and miniatures near the miniatures wargaming tables to drive impulse sales, while the miniatures wargaming club holds its meetings in a public space. Alexandra Kviat, in her sociological survey of how people encounter various spaces for board games (cafes, homes, clubs, and stores), notes that her participants felt uncomfortable and rushed when playing in stores when compared to clubs and cafes. This is especially true of women she interviewed, who felt unwelcome by the heavily male clientele of gaming stores.26

This set of relations links to political economic concerns which miniaturists are barely aware of, if at all. Starting in 2020, Games Workshop moved away from the decades old 6×4’ standard for their games. Replacing it were odd sizes: 44×30”, 44×60”, and 44×90”, depending on how many miniatures are in play. During qualitative research at a miniatures wargames studio in Nottingham, UK, I expressed my puzzlement at the shift to a man who used to work at Games Workshop. It turns out he was privy to the meetings where the table size changed, and the answer was simple. The new table sizes, disrupting the settled upon standard going back at least 30 years, mapped to the sizes of the most popular IKEA tables. Games Workshop had relevant sales data, calculated that IKEA makes the most popular tables in the world, and changed their design paradigms accordingly. The ramifications to this decision are important: designers need to adjust rules, the number of miniatures Games Workshop sells changes, and gaming’s implication in global supply chains takes on more .

Miniatures wargaming tables do not have pre-printed grids on them except for a very few games, such as BattleTech (which also has rules for playing without a grid). The above picture of my group’s regular table should be taken as a standard set-up and suggests the next primary pillar of miniatures wargaming: the use of non-discrete movement.

2) Non-discrete Movement and Seeing the Grid

Avalon Hill’s games typify the used of gridded movement in the early commercial wargame. These simulate large scale conflicts such as the American Civil War and various World War II battles. While classified as wargames, this style physically resembles boardgames: the games take place on a board with demarcated hexes or grids for gaming purposes and rarely, if ever, contain miniatures, opting instead for small cardboard representations of the statistical quality of soldiers, tanks, and the like (see Figure 5).

Miniatures wargames are different. Games take place on a table, as detailed above, but there are no grids or hexes. These games always use miniatures, and the battlefield terrain is three-dimensional, often consisting of elaborate crafting projects in their own right, as I detail below. In the absence of grids, players use measurements in order to determine how and where individual miniatures move. Measuring distance in a grid-less play space comes with the attendant accoutrements of such activity, such as tape measures. Miniatures wargame designers Ford and Hutchinson refer to this as “non-discrete” movement.27

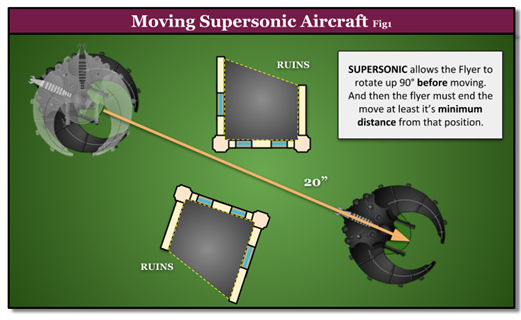

The above photos provide examples of these differences. In Figure 4 is Avalon Hill’s Panzer Leader. Note the hexes and small cardboard playing pieces. Figure 5 shows a game of WFB, with its miniatures, larger gaming space, and lack of grid. Lastly, Figure 6 shows a tutorial image for how to move aircraft in 40k.

The tutorial image is of particular importance. There is a grid, but it is not pre-measured and imprinted upon the play area. Rather, the grid is perceptual and imposed by the players through the use of non-discrete movement during play. Here, 40k serves as a pedagogical tool for a specific way of how to map space in a grid and by measurement. The openness of a miniatures wargame obfuscates this approach. If I have a particular miniature which can move 6” per turn,28 then I am drawing imaginary lines of 6” each turn with the aid of a measuring device. I anticipate my opponent’s movement in turn.

As Bernhard Siegert and Geoffrey Winthrop-Young note, the imposition of gridded perceptions underpins Western conceptions of space.29 Miniatures wargaming is a part of this way of conceptualizing space. During play, game movement is non-discrete and detached from a printed grid, but a perceptual grid is always in mind. During play, a way of seeing and thinking arises as a game plays out over the perceptual grid, one which merges “operations geared toward representing humans and things with those of governance.”30 I measure the space, myself, and it is to be advanced through, taken, or held. Using Siegert and Winthrop-Young’s theorizations of the grid, to impose a grid upon a gridless table is to govern and control it. The perceptual grid imposed in play upon the table is part of an assemblage of multiple such grids.31 The miniatures wargames table is either square or rectangular. When within a square room—that is, most rooms—it is a grid within a grid. If we zoom out once more, the room is one square room amongst others, in a square house on a city block. While such thinking exists within the boardgame style of wargaming, it is the player’s own control over the measuring and occupation of unmeasured space which intensifies this mode of thinking.

This mode of thinking about space becomes dominant during the Napoleonic Wars. Not coincidentally, this is when the first modern wargames arise. The requirements for ever more meticulous war planning during the Napoleonic Wars gave rise to wargames in which representations of troops and supplies were modeled as and through wargames. The new wargames were representative of and derived from new ways of thinking about space and logistics as they came into being during early 19th century modernity. The book Empire of Chance by Anders Engberg Pedersen traces the rise of statistical ways of thinking, particularly about space and time, to this period.32 He notes that new modes of measurement regarding logistics, mapping, measurement, and combat which coincided with the Napoleonic Wars created the conditions of possibility for those same innovations to be applied to other spheres of life and economics throughout the 19th and 20th centuries: modern efficiency regimes, total war, the rise of advanced supply chain logistics, and colonial depredations in Africa. Officers of the time modeled a tremendous amount of math which prior wars did not have. Logistics were considerably more complicated with the rise of transatlantic trade and supply routes, while the Napoleonic Wars saw troop movements across Europe and North Africa rather than in comparatively smaller areas of past wars.

The movement of troops and supplies demanded mathematical modeling: how far can Army A move before encountering Army B? Can I, as a general, push Army A faster and at what cost? Will Army A be undersupplied with munitions if it does so and what does that mean for the inevitable conflict? New battlefield technologies such as advanced artillery and early rifling compounded these concerns. The legacy of this logistical and spatial planning is still with us today in the miniatures wargame. While miniatures wargames invariably model the tactical, rather than strategic layer of conflict, the intent of these games is to model precision in movement and supply.

The wargame as tool of war did not remain within its bounds for long. As wargames and miniatures wargames were commercialized in the 20th century, a specific order of operations to play developed. This order of operations remains even after the even later development of role-playing games and still differentiates the two.

3) The Order of Operations in Miniatures Wargaming

The miniatures wargame, much like the tabletop role-playing game, contains a strong element of storytelling aimed at creating co-authored, spontaneous, improvisational narratives which arise during the circumstances of play. How players achieve this differs from tabletop role-playing, however. In a tabletop role-playing game, each player creates and portrays a single character. Character creation precedes conventional play: rolling dice, fighting villains, gaining experience, and the like. Character creation may be elaborate or complex, but in all cases aims to set the stage for the improvisational play to come. For example, in a study comparing role-playing to stage acting and improv theatre, Sarah Lynne Bowman writes, “Role-playing is most similar to improv in that players enact spontaneous, unscripted roles, but for longer periods of time in a persistent fictional world. Additionally, role-playing involves a first-person audience rather than external viewership, meaning that the other role-players are the only audience members and are also immersed in their roles.”33 This is not to say that role-playing game play is scripted; it is not. Instead, the role precedes and is vital to the ensuing act of play. As role-players design a role for themselves as a first-person audience,34 they find themselves in the position of playwrights as well as actors.

As tabletop role-playing games developed, design increasingly focused on rules which allowed for ease of dramatic portrayal in addition to combat effectiveness. The 1991 publication of Vampire: the Masquerade is exemplary.35 Key to the success of Vampire (and the broader World of Darkness series of games which followed) are a suite of character creation rules codifying personality and mental traits during character creation. Character creation in Vampire is complex and time-consuming, most notably in its “merits and flaws” system, whereby players pay for advantages and disadvantages with points, providing a mechanical link to character portrayal. Players spend enormous effort developing elaborate backstories to justify the mechanics (and vice versa).

John Cocking and Peter Williams, designers of the tabletop role-playing game Beyond the Wall and Other Adventures, refer to this sort of pre-game creation of player characters in TTRPGs as the “lonely fun time” problem.36 They use the concept of “lonely fun time” to describe the counter-productive use of time writing elaborate player character narratives while scouring rulebooks in order to align mechanics with conceived role. While their description is tongue in cheek, it speaks to a persistent problem within role-playing design in the post-White Wolf era. A similar wariness permeates the upper echelons of successful role-playing design in the 21st century, as current trends skew toward lighter, group-oriented character creation and play. Designers of the popular role-playing game Apocalypse World describe their approach as “play to find out what happens,”37 or in other words, the nuances of character creation occur through communal play rather than in solitary exercises.

“Lonely fun time” also reflects a specific order of operations in conventional tabletop role-playing games: first you design a character with a backstory, then you enact the role according to the expectations a backstory would suggest. The largely solitary creation of character backstory is regardless of what the other players, with their own backstories and lonely fun time, might desire. A mighty warrior born in a rural village would be expected to behave differently from a weak wizard raised on the streets of a large city, to use common tropes from Dungeons & Dragons. The sort of solitary creation which typifies “lonely fun time” is no longer uniform in TTRPGs. Rather, it is a problem which TTRPG designers have sought to address in various ways (e.g. establishing intra-character relationships at character creation) over the past 25 years, most notably during the foment of the early 2000s indie TTRPG scene. In other words, whatever one calls “lonely fun time” it has been a known design issue in TTRPGs dating back 25 years, if not longer.

In a miniatures wargame, the order of operations is reversed and hence “lonely fun time” has never been a significant design issue. Each player controls dozens, sometimes hundreds of figures, each one representing an individual soldier or unit: an army of ciphers. It is impossible to offer unique characterizations for each individual. This is not to say that there are no attempts at such characterizations, merely that “lonely fun time” is impossible in a miniatures wargame. Personal backstories are not relevant, at least not to the same degree, even in smaller scale skirmish games. A 40k player may concoct a backstory for a Space Marine unit—for instance, that they are veterans of countless wars—but that backstory does not define the unit’s in-game behavior beyond the barest of statistical measurements (e.g. a Space Marine veteran unit has better weapons). The backstory is for pleasure, rarely manifested in rules beyond the aforementioned statistics, and always returns to the physical presence of the miniatures, themselves. As Meriläinen, et al. put it, “The fiction and the physical miniature exist in symbiosis: the figurine can be an expression of the fiction, crafting it both a physical and an imaginative act. Reciprocally, what happens to the miniature in crafting and in play feed back into the fiction.”38 Most of the pre-action expression in a miniatures wargame materializes in the craft practices of the miniaturing pastime, as the miniaturist paints their miniatures in unique ways or converts (i.e., customizes) them. These expressions have little effect on gameplay. Although many tournament organizers give points for well-painted miniatures, a better painted or highly customized army does not roll or maneuver better than one which is unpainted grey plastic. In the inverse of a TTRPG, stories in miniatures wargames arise almost entirely out of moment to moment play.

One other significant pillar of miniatures wargaming derives from the intersection of table, non-discrete movement, and storytelling through miniatures. A table without grids must be filled with terrain in order to play and, in order to maintain consistency in storytelling and aesthetics, it is often hand crafted.

4) Bricolage, Craft, and Terrain

Craft is an integral part of miniaturist practice, but it is also necessary to play a miniatures wargame. One of the hallmarks of miniatures wargaming is that the table changes with each game. A miniatures wargame is not played on a uniform surface like a boardgame, with setup instructions and grids which are the same for each game. In a miniatures wargame, one places hills, forests, and buildings, never in quite the same place twice, even if the variation in placement is miniscule. To shepherd this style of play, miniatures wargamers need what is termed terrain or scenery. Terrain is crafted, too. At its simplest level, you can buy terrain, assemble it, and paint it, but there is a strong craft tradition in miniatures wargaming around making it from scratch. While there are vendors who sell two-dimensional terrain, they are small and make only rare appearances in store and club play.

Crafted terrain is usually made out of trash and household materials. You can see one of my pieces on my perpetually stained and uneven crafting table below (Figure 7). I made it for a game called Necromunda, an offshoot of 40k centered on warring gangs in the depths of a far-future industrial city. Fictionally, it is a vat of some sort of goo. I made it out of an empty almond tin and a hard drive bay, plus some of my daughter’s old toys. I added a tea light stripped of its casing. Then I painted it and made it look gross.

My creation of this vat is a form of bricolage, an assemblage of the discarded and leftover which creates something new.39 Bricoleurs rearrange and reassemble commodities to create new meanings, in this case the meanings transmitted by games. Necromunda takes place in a dirty, brutal world of advanced extractive capitalism. When I use trash in my terrain building, it transmits the themes and moods of that fictional world at multiple levels of signification. For this reason, Necromunda terrain is some of the most popular terrain to build: it is easy, because we do not know for certain what such a world looks like when it is real, but we recognize that we act as Necromundans by repurposing the detritus of industrial capitalism. The creation of terrain has become a sort of secret handshake amongst miniaturists, where it is a rite to examine terrain and figure out what it’s made from. The terrain crafter as bricoleur recognizes other bricoleurs.

In this last sense, terrain making resembles Hebdige’s designation of bricolage as subcultural language. Noting that “It is basically the way in which commodities are used in subculture which mark the subculture off from more orthodox cultural formations,”40 one could argue that the network of trash-obsessed terrain crafters, particularly online at sites such as The Terrain Tutor and Eric’s Hobby Workshop, resemble a subculture. They create hierarchies of distinction, with those who simply buy mass-produced terrain products separate from the more prestigious subculture of dumpster diving terrain crafters. Handcrafting terrain signifies expertise and subcultural cache, as the recognition of specific pieces of trash within the assembled bricolage of terrain becomes a marker of knowledge. The terrain bricoleur “juxtaposes two apparently incompatible realities,”41 in this case that of a fictional world and our non-fictional world of discarded commodities.

A final difference from other forms of analog gaming is in how miniatures wargames are made. I admit here that this is less a formal element of miniatures wargames play. Nonetheless, the distinctive production methods in the miniatures wargames industry set them apart from other analog game genres and influence their formal elements.

5) The Centralization of Production

Miniatures wargames production requires a high concentration of industry nearby for production at scale. At miniatures studios, all design, art, sculpting, and mass production usually take place in the same building. In my research visits, these locations have painting studios next door to the production room, which is next door to the distribution warehouse. The net effect is that there remains a centralization and concentration of miniatures production that persists where production of other analog games is more dispersed. This is not to say that there is no disbursement in the miniatures wargames industry, particularly in the age of cheap 3D printing, which presents something of an event horizon for the health of the industry,42 but that centralization is still the norm.

This centralization is most realized in Nottingham, UK. The concentration of miniatures studios is so dense that it is colloquially known as the Lead Belt, so named because miniatures used to be made of lead alloys.43 The concentration of miniatures wargames production in this specific local context leads to talent exchange, sharing of materials, and a sociality which influences design, as well as cultivating a common interest in topics (e.g. a particular interest in WWII and the Napoleonic Wars) and aesthetics.44

Conclusion

I conclude where I began: I do not consider this article the final, settled definition of miniatures wargames as a genre of analog game. My impetus for studying the ludic and production elements of miniatures wargames derives from the relative absence of study of these matters when compared to other genres of analog game. Defining the miniatures wargame as simply an analog game which uses a lot of miniatures is not enough, partly because it is not true (skirmish games use few miniatures while some boardgames use many) and partly because noting the presence of miniatures does little to explore the specificities of the form. The centrality of the table, the use of non-discrete movement, the peculiar nature of game-derived storytelling, the prominent use of bricolage in terrain building, and the industrial/craft hybridity which necessitates a more centralized production than other analog game forms all distinguish miniatures wargames. I sincerely hope that my definitions entailed here spark conversation and pushback from experienced game designers and academics, alike.

–

Featured image by wirestock on Freepik.

–

Abstract

This article provides a preliminary description and definition of the miniatures wargame. Rather than defining the miniatures wargame via the use of miniatures, which is obvious, it locates the specificity of the miniatures wargame in the centrality of the table to play, the use of non-discrete movement, the prominence of bricolage style craft in customization and terrain building, the order of operations in ludic storytelling, and the centralization of the hybrid industrial/craft miniatures wargames industry. The article aims to spark discussion of the specificity of miniatures wargames as a genre of analog game.

Keywords: miniaturing, miniatures wargames, Warhammer, design, game production, game materials, craft, gaming table

–

Ian Williams studies relationships between craft and industry in the games industries. He received his doctorate in communication from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Prior to this, he was a labor reporter and cultural critic.