Introduction: How Rules Mediate Transmedia Narrative in TTRPGs

Tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs) remediate and remix various media and genres, and they are often part of larger transmedia storytelling projects.1 As Paul Booth explains, “Transmediation of games requires both the active participation of the audience as well as recognition of key attributes of the core medium.”2 Though Booth was speaking specifically about board game adaptations of The Walking Dead franchise, the same principle applies to roleplaying games. Roleplaying games, however, offer a different set of media and narrative affordances and constraints than board games. Consequently, a close reading of the “the key attributes of the core medium” is warranted. Scholars have considered the materiality and positionality of board games as media,3 studied TTRPGs’ intersections with transmedia storytelling,4 their mediatization,5 how TTRPGs facilitate the construction of narrative and immersion,6 how TTRPG systems facilitate identity and the transmission of cultural values,7 and more. Here I want to add to these conversations by looking at how transmedia adaptation in TTRPGs can often lead to what videogame designer Clint Hocking has described as “ludonarrative dissonance,” when the narrative and ludic elements of a game are at odds with one another—when it “suffer[s] from a powerful dissonance between what it is about as a game, and what it is about as a story.”8 While Hocking was speaking about how a videogame’s mechanics reflect or frustrate a story’s thematic elements, I hope to expand on the notion to explore how tropes and expectations from genres in transmedia spaces can further serve as sources for ludonarrative dissonance looking at two editions of the Marvel Super Heroes Role-Playing Game (MSHRPG).

In prior work, I have argued that TTRPGs are not a medium per se, “but rather a hypermedium comprised of several parent media, remediated and repurposed for the sake of the rhetorical action they’re intended to facilitate.”9 I see TTRPGS as a multi-modal genre—one that draws on various media to help participants meet the needs of a recurring rhetorical situation: the co-creation of a shared narrative.. As rhetorician Carolyn Miller explains, rather than static categories, genres are “typified rhetorical actions based in recurrent situations”10 whose definition “must be centered not on the substance or form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish.”11 Genres facilitate social action, inform (and are informed by) audience expectations, and more crucially, they draw on genre knowledge to address a new situation. Gamers participate in the genre of the tabletop roleplaying game session while drawing on several other genres like improv theater, fantasy novels, gaming rulebooks, and more. When weaving genres and media together to address a new rhetorical situation, game designers can draw on familiar genres and media—even if they are incongruous or inconsistent for the new situation such as drawing on crunchy simulationist mechanics for a more narrative-oriented game. In turn, many of the audience expectations, genre features, and media features can often conflict with one another. This flexibility and adaptability of medium and genre are what make TTRPGs so rich, but as this analysis will demonstrate, these conflicts can also exacerbate ludonarrative dissonance.

The practice of translating genres of fiction into roleplaying games (RPGs) has been a feature of TTRPGs for as long as they’ve existed. Dungeons & Dragons’ incorporation of Tolkien-isms such as balrogs, hobbits, and treants (though later with the more identifiable/brandable intellectual property or IP markers removed) is one of the earliest examples of this phenomenon, followed by Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Elf Quest, and so on. Recent TTRPG adaptations include Transformers and Avatar: The Last Airbender, both released in 2022, and 2023’s Marvel Multiverse Roleplaying Game (MMRPG), the latest in a long series of attempts by different companies at translating Marvel comics IP into a TTRPG. Given the increasing cross-pollination, transmedia storytelling, and cross-platform marketing that occurs in these spaces such as making unique D&D-branded cards for Magic the Gathering or invoking novels and other setting-specific IP for video games such as Larian Studio’s Baldur’s Gate 3, more attention to the work of transmediation in TTRPGs is clearly needed. As noted earlier, it is perhaps unsurprising that most of the scholarship on the topic deals with transmediation in digital spaces. Therefore TTRPG scholars and analog game designers can learn a lot from this earlier, pre-digital form of transmediation to think about how genre, mediums, rules, stories, and more interact and get remixed.

Specifically, I argue that roleplaying game designers who adapt existing media properties must navigate often conflicting or competing impulses in design informed by the affordances and constraints of various parent genre and media. I share a case study of two editions of the Marvel Super Heroes Role-Playing Game (MSHRPG), released originally in 1984 (which will be called “Original Set” for the rest of this essay) with a later revision into an Advanced rules set (which will be referred to as “Advanced Set”) in 1986. The MSHRPG is a fruitful site for considering transmedia in that it features the first adaptation of the Marvel comics superhero genre to the genre of “pen-and-paper” roleplaying game. The superhero comics genre is well established and features various well-known genre tropes, making this initial edition ideal to examine early transmedia adaptation.

The revision of the 1984 Original Set to the 1986 Advanced Set is particularly interesting because it demonstrates how even seemingly minor changes in the mechanics facilitate a vastly different play experience regarding fidelity to the parent genres and narratives. In remediating reader/player expectations and adjusting them to the “advanced” sub-genre of roleplaying games, ludonarrative dissonance of a unique sort is introduced to the game wherein attempts in the design to simulate “reality” conflict with the ability to simulate the sorts of narrative flow. Each of these editions also reflect the norms and expectations around gaming and comics during a pivotal time in both industries, highlighting the complex rhetorical interplay between comics audiences, writers, storylines, gamers, designers, and markets in each industry and hobby. As Henry Jenkins explains, “In the ideal form of transmedia storytelling, each medium does what it does best—so that a story might be introduced in a film, expanded through television, novels, and comics, and its world might be explored and experienced through game play.”12 However, a hypermedium like the TTRPG has several medial affordances and what it “does best” can vary depending on the needs of the given rhetorical situation, whether to provide a sort of systems granularity that supports “realism” or a broad resolution system that covers a swath of tropes associated with a particular genre of fiction such as comics.

Developing the Marvel Super Heroes RPG

MSHRPG finds its beginnings in a years-long homebrew game that designer Jeff Grubb ran for friends at college before his time at TSR, the company that eventually published the game. TSR was able to secure the license from Marvel, and TSR paired Grubb with Steve Winter to act as editor and coauthor. They began playtesting iterations of the rules with other designers and young children.13 Grubb and Winter aimed for a design that was accessible, that was easy to understand for first-time users, and that catered to casual comics fans. At that time, the comics industry was moving to the direct market, and as Grubb explains,

We were looking at a new game to break into, get a new audience, not sell it necessarily to the same group that was playing D&D, but sort of take that group and expand out on it. And at this time was when comic books were expanding as well with the direct sale marketplace. It used to be that if you’d go to the local drug store, you could buy the comics. They were there every month. Well, the direct sale market basically were working through a distribution channel, like magazines. And the direct sale market of comics, basically the shop got the comics directly from the printer. So they cut out the middleman and it was a way of making sure that you had all the comics you needed.14

The effects of this shift were far-reaching for the comics industry, but for the purposes of this article, it meant that comics shops could cater directly to comics fans. This, in turn, allowed them to market ancillary products like action figures, t-shirts, posters, and more. MSHRPG, then, provided retailers with a novel item to sell to this fandom. RPGs were not commonly sold in these relatively new venues, so it enabled TSR to target a new audience directly.15 The desire for a new audience strongly influenced both the presentation and design philosophy informing the game: it would speak to the new audience’s familiarity with comics while instructing them in how to remediate that familiarity to the new genre.

The 1984 Original Set: Adapting Comics to RPGs

Style and Visual Cues

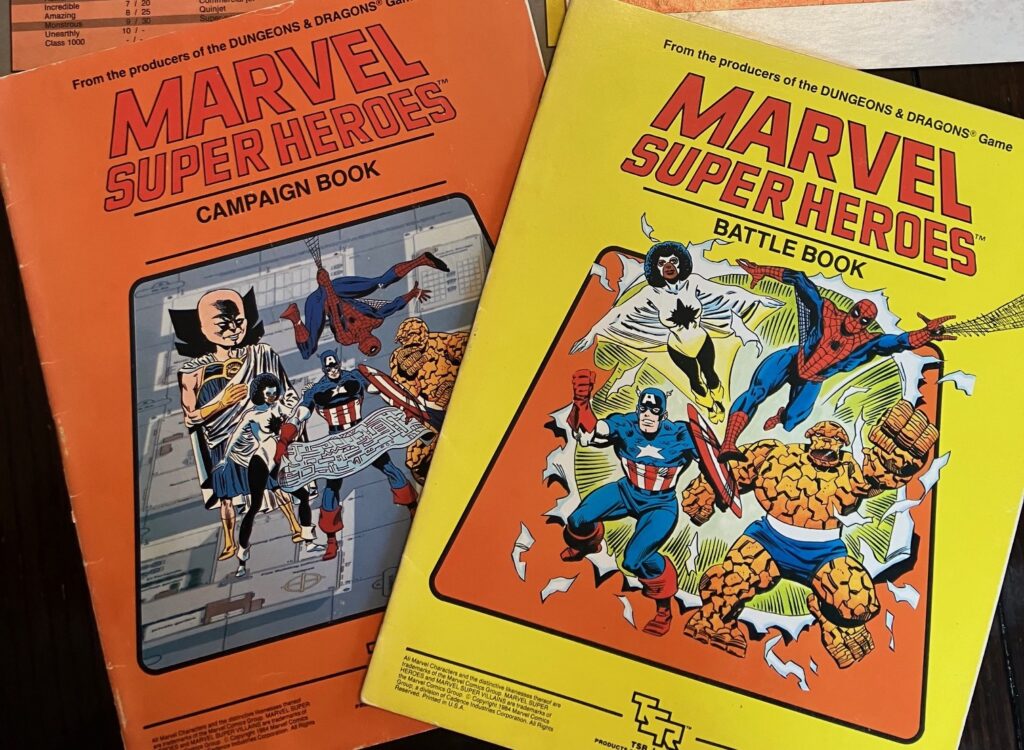

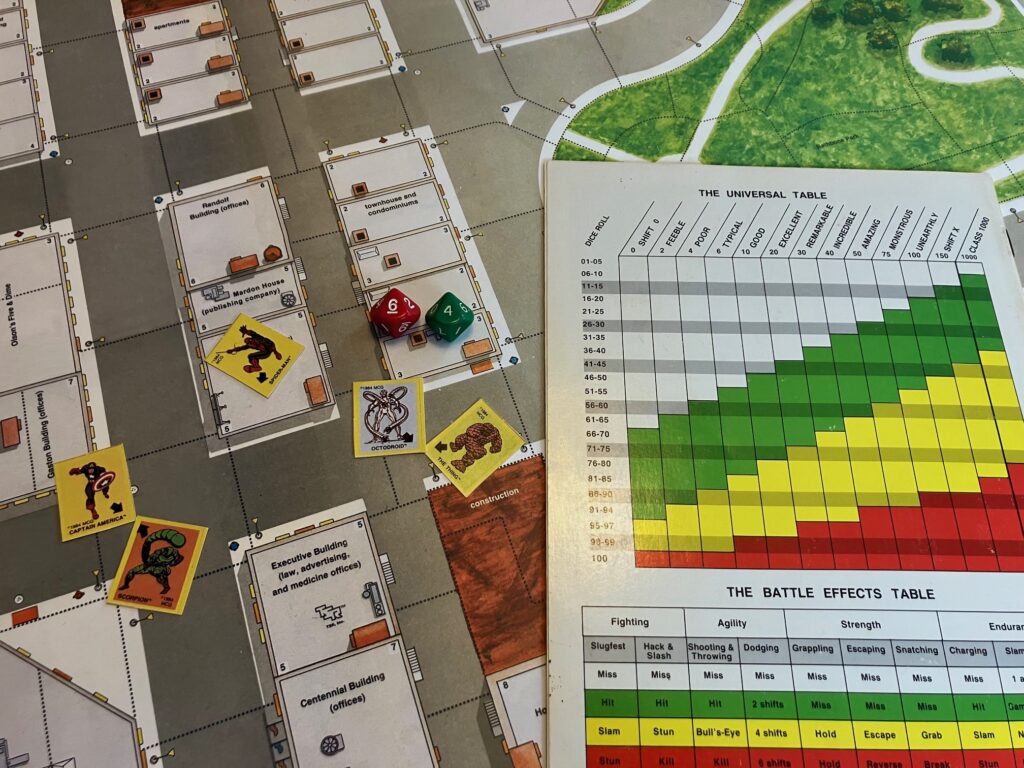

The Original Set of MSHRPG was packaged in a bright yellow box bearing cover art drawn by famed Marvel comics artist John Romita, Sr. It contained a yellow “Battle Book,” an orange “Campaign Book,” as well as a glossy cardstock foldout containing the full-color character art and game statistics for eight established Marvel heroes such as Captain America, Spider-Man, and The Thing. There were also several accessories such as a thick full-color cardstock block of “chits” for the map (to stand in for miniatures), two ten-sided dice, and a double-sided, full-color poster map. One side of the map showed a city neighborhood and the other various interiors to be used as a sort of “board” in the game. The game could be played in one of two modes: a boardgame-like battle simulation between the characters included in the set or a more traditional TTRPG. Accordingly, the two rulebooks differed from the typical division of a TTRPG rules of a players’ manual and a game master’s (GM) manual. Newer players could simply use the Battle Book to run MSHRPG like a board game, staging fights between their favorite Marvel characters. If they wanted to run a more traditional RPG-style game, they referred to the Campaign Book.16

The black and white interior art largely came directly from the artists working at Marvel (the “Marvel Bullpen”), and the line art was provided by Al Milgrom, a regular Marvel artist known for adhering to the Marvel “house style” that was prominent at the time. The visual style of the books is thus in accord with what readers of Marvel comics would expect. Moreover, the books feature several examples of paneled sequential art to explain game concepts. The inside front cover, for example, depicts a six-panel sequence that alternates between scenes of the players at a table roleplaying the events and scenes enacted in the game world. Each panel is captioned with dialogue from the players or characters, demonstrating how the heroes stop a robbery. Rather than explaining mechanics, this bit of art explains the genre of the TTRPG through the medium most accessible to comics fans: comics. Other pieces of sequential art include a three-panel illustration depicting Spider-Man swinging down to scoop a dog out of the way of an oncoming truck. This sequence occurs below a textual explanation of the core mechanic of the game (the FEAT roll). The final sequence of the Battle Book demonstrates the basic combat mechanic of the game, captioned with explanations of the game mechanics facilitating the action in each panel. Finally, single panels are used throughout the text to illustrate various rules and mechanics, such as Spider-Man holding his breath underwater while being grappled by an octopus.

The Marvel visual style is reinforced by Steve Winter’s prose style, which very much mimics Stan Lee’s bombastic editorial and authorial voice from the comics. Designer Grubb explains, “I would be doing design work, and he [Winter] was basically doing the pitch as far as how the rules are presented. A lot of people were thinking it was Jeff: ‘oh, he’s doing the whole Stan the Man thing—face front, true believer!’ That was Steve! And he did an incredible job. Marvel was as good as it was—that first one we did—because of Steve Winter.”17 In particular, the books feature prominent Marvel characters (most especially Spider-Man) explaining various rules in character, often breaking the fourth wall. For instance, in the bottom right corner of the first page of the Battle Book, there is an illustration of Spider-Man using his web to turn the page, encouraging the reader to join him on the next page. There are also asterisked “Editor’s Notes” from Steve Winter in the style of Marvel’s editors notes, such as “See ‘It’s Clobberin’ Time,’ p. 10—Sentient Steve.”18 Comics fans encountering this material for the first time would obviously know they are navigating a new genre, but the game draws on the newcomer’s media and genre repertoires to help them acclimate to the new medial environment.

Mechanics and Genre Tropes vs. “Realism”

The core mechanic of MSHRPG is the FEAT roll: (“Function of Extraordinary Ability or Talent”). When a player or the Judge (the game’s term for “Game Master” or “GM”) wishes their character to perform an action beyond the ordinary, they attempt a FEAT roll. They roll two 10-sided dice or 1d100 (one counting as the tens place, the other the ones place) to result in a number between 1 and 100. They then consult the Universal Table found on the back cover of either book. The numbers designate the row consulted, and the columns are the Ability being tested. The player checks the result to determine the color of the result: white (failure), green (a modest success), yellow (a greater success), or red (the best success).

For example, if someone were playing a character with a Fighting of Incredible (40) and rolled a “62” when attempting to punch a villain, they would check the Universal Chart to find that they scored a “Yellow” result, hitting the villain and potentially slamming them into another area. The system is simple enough for the target demographic of newcomers to the hobby to understand, flexible enough to apply to the variety of situations commonly found in the genre, and variable enough to produce different outcomes, thus leading to further complications in a given encounter. For its design, Grubb adapted mechanics from old Avalon Hill and SPI19 wargames: the “combat results tables.”20 In these games, comparative unit strength was typically more of a deciding factor of success rather than the dice (as in most RPGs), which accounted only for small differences between units. Grubb retained this feature by introducing a mechanic adopted from the spy game Top Secret that he labeled “Karma.”21

Karma Mechanics and “Feet of Clay”

At a glance, Karma could be considered a “hero point” system similar to other games that rely on probability to determine success such as the fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons’ Inspiration mechanic. Basically, it is a resource that is spent on a 1-for-1 basis to modify die rolls: spending 30 Karma will increase a roll by 30 points on the die. Forty points of Karma can also be spent to reduce incoming attacks by a color rank, allowing characters to be strategic about the sorts of attacks they are willing to suffer. Finally, it can be saved to eventually improve the character’s game statistics. However, Karma is a much more free-flowing resource in MSHRPG than hero points are in most other TTRPGs, and it has a profound impact on play and on the implied ideologies of the game world. In short, this mechanic—combined with the Universal Table—facilitates a play experience much more in alignment with the tropes of the superhero genre than with a traditional TTRPG’s focus on simulating reality. It is thus a fundamental feature for how this TTRPG remediates the superhero genre from the comics.

For instance, Karma is awarded to heroes for adhering to Marvel comics’ overarching tropes: heroes with “feet of clay” who struggle to balance heroics with relationships and personal obligations, heroes who navigate moral dilemmas between least harm and deontological imperatives. In MSHSRP, characters are awarded Karma for rescuing people, defeating villains, stopping crimes, engaging in public service, cracking jokes, honoring their commitments to work and family, and so on. They lose Karma for committing crimes, for property damage, for breaking commitments, and for public defeat. Perhaps most importantly, they lose all Karma if they kill (or allow someone to be killed). This system sets up a sort of moral roleplaying calculus that mimics many of the storytelling tropes of Marvel comics: if Peter fails to make his dinner date with May (-10 Karma), he can potentially stop the Rhino’s rampage (+50 Karma for defeating the Rhino, +20 for preventing a destructive crime). This can, in turn, lead to further storytelling consequences and drama. As Grubb explains, “[T]hat fit in with how Marvel comics work. It was the mid-80s. Spider-man would have to meet with Aunt May but be interrupted by the Kangaroo. These were the sorts of stories we were embodying and simulating.”22

More importantly, given how free-flowing Karma is in the game, the hero’s Abilities and powers are less determinative in their success for a given FEAT roll than the amount of Karma the character has. The defining feature of a character in MSHRPG—their most determinative factor in success in the mechanics—is thus not their powers or scores (their “game stats”) but that they are a good person (as conceived by the bronze age Marvel comics). A hero with an Incredible (40) Fighting score may need less Karma to succeed in punching a villain than a hero with an Excellent (20) Fighting score, but if the hero with Excellent (20) Fighting has performed more consistently within the parameters of Marvel comics morality and aesthetics, she will be more effective overall.

The Karma mechanic also combines with other mechanics to privilege simulating superhero comics genre tropes over simulating “realism.” For instance, a mortared brick wall in the MSHRPG has a Material Strength of Good (10). This means that normal people have a small chance (2%) of breaking through a brick wall. While not being terribly realistic on the surface, when considered alongside Karma, it facilitates comic book genre tropes well: the desperate captive finds a hairline crack in the wall and implausibly bursts forth, her previous good deeds and commitments motivating her to press forward; a desperate hero swings a wild haymaker at a villain, smashing him through a brick wall. A hero who has accumulated Karma can make the improbable become certain.

Villains also have Karma rules in MSHRPG. They receive it for performing crimes, beginning encounters with both their base amount of Karma as well as a bonus for the type of crime they’re committing. Interestingly, Silver and Bronze Age values are in play here as well, as villains will still lose a modest amount of Karma for killing (unless the victim is a henchman of the villain). They also gain Karma for exposition, for capturing rather than killing heroes, for putting heroes in death traps, and for property damage. In short, the mechanics reward the gamemaster for abiding by comic tropes by providing them with enough Karma to prolong fights with the heroes and heighten the uncertainty of the outcome.

Karma is thus more than a “carrot and stick” mechanic to encourage or discourage certain approaches to play: it adds stakes to those choices and facilitates meaningful choices around resource management. In combat, for example, villain teams can pool Karma. Along with Karma’s ability to reduce the effectiveness of incoming attacks, fights are often more akin to playing poker against the Judge, each side wanting only to bet enough Karma to gain a desired result but occasionally needing to spend more to avoid their move being negated by the other’s Karma expenditure. Combined with the variable degrees of success, players can thus weigh probability against outcome to make informed and meaningful choices about even relatively small actions (dodging, attacking, etc.). As Joris Dormans explains, game mechanics and the dice can contribute “to the feeling that the characters’ actions affect the game world and that the player has some control over the fate of his or her character and by extension over the direction of the game.”23 Karma thus provides a means of steering exerting control over the narrative beyond mere probability.

For instance, heroes can increase the damage inflicted on an opponent by ripping up the terrain and using it as a weapon (a common trope in the superhero genre). Doing so, however, comes at a small price to Karma at first, becoming greater should the damage spread. Conversely villains may sacrifice a turn to cause havoc and property destruction, losing an opportunity to harm the hero but recharging some lost Karma. The dynamics of the fight inform the decisions around Karma expenditure: losing Karma to damage property (and thus end the fight sooner) may provide a net Karma gain, but if the villain is also damaging property, the hero might abstain to avoid a greater Karma loss.

Spidey vs. Rhino, or, Using the Rules to Emulate the Fiction

This calculus extends to other sorts of problem solving and choice-making in the core combat system, which further seeks to facilitate the genre. Consider, for example, a fight between Spider-Man and the Rhino from the Marvel comics. In Rhino’s first appearance in Amazing Spider-Man #41, Spider-Man is incapable of directly harming Rhino—Rhino’s armor deflects Spider-Man’s first blow. Instead, Spider-Man relies on other tactics. For example, he dodges out of Rhino’s way, letting Rhino hurt himself by hitting the objects behind Spider-Man. Spider-Man then webs Rhino up to buy himself time and wear Rhino down. Finally, Spider-Man charges him, ultimately knocking Rhino out.

The MSHRPG mechanics facilitate this sort of dynamic fight. Because Rhino’s Amazing (50) Body Armor is greater than Spider-Man’s Incredible (40) Strength, Spider-Man cannot simply strike Rhino with his fists. Rather, he has other choices he can make. For instance, he can tear up the scenery to use as a melee weapon (such as a telephone pole or errant motorcycle), granting him a +1 column shift to his damage. This would equal the Rhino’s Body Armor; while this wouldn’t directly damage the Rhino, it would now leave Rhino subject to being slammed (and thus stalled) or Stunned, potentially ending the fight there. Spider-Man accepts a bit of collateral damage (-5 to -25 Karma) for a slight chance to end the fight. Spider-Man can also attempt to web Rhino up. In game terms, if Spider-Man is successful, Rhino must spend a turn attempting to break free. Given the webs—Monstrous (75) Material Strength—are stronger than Rhino’s Incredible (40) Strength, he will have to spend a great deal of Karma on the attempt. This, in turn, makes him less likely to avoid Spider-Man’s attacks, simulating the comics’ depiction of him getting worn down while fighting his way out of the webbing.

Alternatively, Spider-Man can Charge the Rhino. This maneuver gives him a much greater increase in damage, but carries with it the risk of missing and thus potentially harming himself after hitting a wall or leaving himself stunned and vulnerable to attack. Further, Spider-Man can also bait Rhino and dodge Rhino’s Charge. This plays to Spider-Man’s high Agility score, meaning less of a Karma gamble, but a greater penalty should he fail. In each of these scenarios, combatants can be Slammed over distances, thus emphasizing the importance of placement and movement in the fight. In short, the mechanics of the game emulate what readers see on the comics page well. It may not be terribly realistic for the armored Rhino to be knocked out by telephone booths and wooden telephone poles, but the game privileges genre emulation over “realism” while also supporting player choice and agency: the Rhino is not an unbeatable figure but rather a problem to be solved using the available resources and game moves. To return to our opening quandary for game designers, the 1984 edition of the game privileges fidelity to the parent genre and meaningful player choice and agency against “realism” and granularity. The 1986 edition, by contrast, made considerably different choices that lean more toward realism.

The 1986 Advanced Edition: Remediating Rules and Responding to Trends

The original game proved immensely popular and was supported by an array of adventure modules and setting supplements. Two years later, the release of the 1986 Advanced Set of the MSHRPG coincided with the emergence of two significant trends in comics and roleplaying games. First, comics were fully amid the so-called “Iron Age,” wherein darker, more mature themes prevailed. 1986 saw the publication of both Watchmen and Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. And though these were watershed moments in the Iron Age, they were preceded by a more general trend toward more mature storytelling in the superhero genre such as Miller’s run on Daredevil, the rise of anti-heroes such as Punisher and Wolverine, and Iron Man Tony Stark’s alcoholism. The MSHRPG books reflect this sensibility with antiheroes being featured on many of the covers of the Advanced set releases.

Second, there was a trend during this period among tabletop roleplaying game publishers to release advanced or revised versions of their rule systems. This trend was largely influenced by several factors, including the growing popularity of RPGs, the maturation of the gaming industry, and the desire to refine and expand upon existing game mechanics. While Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D) is the most obvious of these games, other TTRPG publishers followed suit by releasing advanced editions or revised rulebooks for their games. For instance, Chaosium, Inc. released in 1983 an advanced edition of their popular horror RPG, Call of Cthulhu, which included expanded rules for character creation, combat, and sanity mechanics. Other RPGs like Traveller, Warhammer Fantasy, and Fantasy Trip (which was later changed to GURPS) published similar releases. Even the board game HeroQuest had an “Advanced” TTRPG release. These advanced versions of the game allowed publishers to cater to both new players and experienced veterans of their games. New players could “onboard” with the original or basic rules and gradually delve deeper into the more complex mechanics of the advanced version. Experienced players could enjoy the added depth and complexity provided by the advanced rules. But more than this, the often-baroque rules associated with so-called advanced editions of games promised to facilitate a certain realism via more granular outcomes and mechanics.

Advanced MSHRPG featured several changes that reflected these sensibilities. Many of these changes were additive: new rules for avoiding attacks, more granular forms of damage and attack types, more powers and talents, and more options in combat. It also reflected Iron Age comics sensibilities in its greatly expanded weapon and equipment lists. Compared to the firearms featured in the Original Set, guns were also made more dangerous. Most importantly, however, is that many of the core rules of the Original were subtly changed in seemingly minor ways that had profound effects on play. For instance, in the Original Set, all players received a full Karma award for participating in an encounter. In the Advanced Set, Karma awards are divided among all participating heroes. Alongside players losing the ability to reduce incoming attack results through Karma expenditure, this resource (being a good person) became far less the deciding factor of a character’s effectiveness than did their abilities. Further, in not being able to reduce incoming hits, dealing and mitigating damage became far more important. These changes, along with the newfound availability and utility of guns, made for a far more Iron Age-oriented game. With Karma awards being only a fraction of what they were in the prior version, killing enemies made more sense: even with the complete loss of all Karma, it would be a relatively minor setback given the comparatively small amount that heroes would begin with in the encounter. Further, despite losing Karma upon killing a villain, they would still be awarded Karma after the encounter for preventing/stopping a crime, thus possibly resulting in a net gain for the hero (however small that may be).

Many of these changes, however, often bore incoherent results. This is likely due to conflicting impulses driving the design: fidelity to the Original set (which privileged comic book genre emulation) versus the more simulationist (re: realist) impulses of the genre of so-called Advanced roleplaying texts. That is, the Advanced rules attempted to simulate the real world via detailed (and often baroque) mechanics while also trying to drive toward universal systems that cut across contexts—even when those mechanics may not cleanly facilitate the desired effect.

For instance, in the Original Set, the consequence of falling is simply a matter of determining the number of stories fallen: the character loses 10 Health per floor. If, for example, someone fell from a 15-story building, they would take 150 damage. Given that an average person would have roughly 24 Health (and heroes might have several hundred Health depending on their power level), it emulates the comics genre fairly well and resolves quickly. In the Advanced set, however, the rules for charging an opponent are appropriated and applied to falling: the implication being that falling is a form of charging at the ground. However, the rules around falling and charging are explained inconsistently from the examples provided, which seem to imply that the damage would be equal to just the material of the ground: typically 20 or 30, regardless of the height fallen. This contradicts the “FAQs” provided at the time by TSR’s Skip Williams in Dungeon Magazine, which implied that damage would equal the number of floors fallen in a given round, up to a maximum of 20.24 Either instance results in the average person with 24 Health falling 20 stories, landing, and walking away. This does not seem to simulate either realism or the genre. Rather, it reflects a taste in “Advanced” systems of the time for mechanics that transcended particular situations and could be applied broadly. That is, to address situations that vaguely looked like Charging—such as falling, a “fastball special,” vehicular crashes, and more—the rules adapted the Charging rules, even when the range of possible results couldn’t match the narrative. Realism is touted as the driver behind the mechanics even when they lead to unrealistic results.

The emphasis on realism is reflected elsewhere in his Dragon Magazine column when Williams responded to a fan question regarding the table on leaping distance: “According to designer Jeff Grubb, this information was extrapolated from real world numbers and existing game data.”25 In sum, early examples such as this demonstrate the sometimes conflicting impulses between unified mechanics and attempts at simulating realism inherent in the genre of advanced TTRPG rulesets. But more striking than this failure of design is that the new mechanics often fail to simulate the parent medium/genre (Marvel superhero comics) in favor of privileging the genre of the “Advanced TTRPG.” To explain, I return now to the example of Spider-Man versus the Rhino.

Spidey vs. The Rhino, Round Two, or, When Rules Frustrate the Fiction

In the Original Set, Spider-Man has four immediate options beyond merely punching Rhino to defeat him: tearing up the scenery to use as makeshift weapons, dodging Rhino’s charge, charging Rhino, and/or webbing up Rhino. In Advanced, the situation is quite murkier. Spider-Man, for instance, can no longer employ makeshift weapons against the Rhino. The Advanced set has codified Material Strength in relation to weapons. Even the strongest materials such as Osmium Steel would only bump Spider-Man’s damage to 46, which would not be enough to provoke a potential Slam or Stun. This common feature of the comics page is thus not available in the new edition of the game.

Similarly, dodging the Rhino’s charge is no longer a viable option. The Original set’s option to spend Karma to reduce the effectiveness of an incoming attack is no longer available. This makes the maneuver even more unfeasible for Spider-Man: performing morally good works is no longer a guarantor of success. Spider-Man is far more likely to be hit than not in the new rules. Even if it were, the attempt would still not be worthwhile due to revisions in the Slamming rules, because anything on the map the Rhino would Charge into—accidentally or otherwise—would not be strong enough to damage the Rhino. Like the previous example, this common trope in the comics is no longer an option in the revised rules—more realistic, perhaps, but not emblematic of the fiction.

Despite seeing Spider-Man charge the Rhino on the comics page, players attempting the maneuver in the Advanced rules would find such a move actually harms Spider-Man. The Original set used a +1 Column Shift modifier to damage for each Area charged through (thus increasing Spider-Man’s damage from 40 to 100). In the Advanced set, only two points of damage are gained for each Area. Spider-Man’s damage would increase only to 46. Further, in a nod toward realism, the new rules discourage charging an opponent with greater Body Armor than the hero’s strength: “If the defender’s Body Armor is greater than the damage inflicted by the attacker, the damage is rebounded onto the attacker” (Player’s Book, p. 27). Rhino’s Amazing (50) Body Armor is greater than the 46 damage Spider-Man would now inflict. Charging the Rhino would now result in Spider-Man, not Rhino, would take the damage of his own charge. This maneuver is thus no longer a viable choice for players.

Conclusion

I share these above examples to illustrate how, while seemingly additive and expansive, the design impulses toward realism and universality in mechanics (a feature of the Advanced TTRPG genre) ended up being subtractive—both from the fidelity to the parent genre/medium as well as to actual play experience: there are now fewer viable option for players in the new edition. The newer edition attempted to privilege granularity and realism; this was always going to be at odds with the Original Set’s emphasis on comics genre tropes and speed of play. The revision attempted to revise elements of the RPG genre of the “advanced rules set” alongside a revision of the “superhero comics genre” in a way that made the express purpose of the initial rules set—to, as Grubb put it, “embody and simulate”26 the sorts of stories seen on the Marvel comics page—unfeasible. Players thus experience ludonarrative dissonance.

It may be tempting to attribute the dissonance of the Advanced set of MSHRPG to poor editing—after all, original coauthor and editor Steve Winter did not contribute to the revision. One might also suspect rules bloat or a lack of playtesting. But this essay is not concerned with identifying design flaws, nor is it a paean to the Original Set, which was itself a product of its time. Rather, my aim has been to explore the complex interplay between medium, genre, and rules-as-medium; between designers, markets, comics audiences, and gamers; between audience expectations, media trends, and game mechanics. Game rules are inherently rhetorical: they facilitate, direct, and at times frustrate human social action. The social is always already rhetorical, and rhetoric tends to crystallize in genres. If we view TTRPGs as a genre that enables typified social action, then the media affiliated with them—books, dice, computers, and rules themselves—become constitutive features of that genre.

Because TTRPGs draw from, adapt, remix, and remediate multiple genres and media, design conflicts are not only common but perhaps inevitable—especially during kairotic cultural moments when designers must respond to multiple, competing inflections in a rhetorical situation. In Jeff Grubb’s case, significant shifts were underway in both the comics and TTRPG industries. Given the trends of the time, it would have seemed natural to attempt an “advanced” version of the game. Grubb drew on conventions from a familiar genre—the advanced TTRPG rules manual, with its emphasis on realism and mechanical granularity—and applied them in a context where those conventions may not have translated cleanly: the revision of a TTRPG built to emulate the stylized, often fantastical genre of Marvel comics. As seen in the Spider-Man vs. Rhino example, the Advanced rules’ commitment to realism didn’t just complicate gameplay—it actively foreclosed the creative tactics that defined the Original Set’s tone. This kind of mechanical narrowing reflects broader tensions in transmedia design.

This case thus highlights the risks and possibilities of adapting across genres and media within the TTRPG space. When designers import conventions from one genre into another—particularly during moments of industrial, cultural, or rhetorical transition—they risk introducing frictions not just between story and system, but also between audience expectation and ludic possibility. These moments of ludonarrative dissonance are not merely design missteps; they are deeply rhetorical events, emerging from the social negotiations of genre knowledge, market demand, and medial constraint. For designers, this means attending not just to balance or simulationist accuracy, but to the rhetorical resonances of genre conventions they import. For scholars, it invites an expanded vocabulary for discussing design choices not as neutral technical decisions, but as situated responses to cultural pressures and media histories. This case is only one example of how genre friction shapes play. Further research might examine how contemporary TTRPGs negotiate similar tensions in transmedia franchises like Star Wars, Critical Role, or The Witcher across even greater ranges of media and parent genres.

As TTRPGs continue to evolve in increasingly transmedial contexts—entwined with streaming, branding, and cross-platform storytelling—the challenge of navigating these rhetorical tensions will only grow. Attending to TTRPGs as rhetorical genres, rather than fixed media forms, enables scholars and designers to better understand how these games function in practice: as collaborative, contingent, and often messy negotiations of meaning. If nothing else, MSHRPG reminds us that every die roll, rule tweak, or stat block participates in a larger rhetorical system—one that not only reflects but actively shapes how we imagine, share, and inhabit transmedia storyworlds together.

–

Featured image by Lucas Mota, free to use, from Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/photos/a-pile-of-toy-figurines-sitting-on-top-of-each-other-AzjavCqyQRc.

–

Abstract

While most transmedia scholarship has focused on narrative and its permutation across digital platforms, earlier analog examples—especially in tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs)—remain valuable for exploring how different media enable or constrain storytelling. This essay examines how transmedia adaptation in TTRPGs can produce ludonarrative dissonance, a conflict between a game’s narrative and ludic (gameplay) elements. Through a rhetorical analysis of the “Original” and “Advanced” editions of the Marvel Super Heroes Role-Playing Game (MSHRPG), I show how dissonance can emerge when designers attempt to reconcile the fantastical conventions of the genre of superhero comics with rule systems drawn from TTRPG genres that prioritize realism and mechanical granularity. These tensions illuminate the stakes of adapting across media and genres in the TTRPG space.

Keywords: Transmedia Storytelling, TTRPG, Marvel Super Heroes, Ludonarrative Dissonance, Genre Theory, Game Mechanics, Rhetorical Analysis

–

Daniel Lawson is a Professor of English at Central Michigan University, where he serves as the writing center director. He has published on rhetoric, writing centers, comics, and game studies. His work in games studies have appeared in edited collections such as Guns, Grenades, and Grunts: First Person Shooter Games as well as Roleplaying Games in the Digital Age: Essays on Transmedia Storytelling, Tabletop RPGs and Fandom.