There is a clear problem of representation in games and — more broadly — in the cultures produced by games. This problem in representation has most recently yielded controversies such as #gamergate1, but it is also more or less responsible for debacles such as the PAX dickwolves saga, and the recent death threats to Anita Sarkeesian spurred by her “Tropes vs. Women in Games” series. Outside the spotlight of digital games, some members of other game communities, such as Ajit George2 and Shoshana Kessock3, have been outspoken about problems of representation at Gen Con4, North America’s largest tabletop game convention. Even in Gary Alan Fine’s classic book, Shared Fantasy, the distinction between reality and fantasy for role-players is considered “impermeable,” despite the sociologist’s own admission that “[frequently] non-player male characters who have not hurt the party are executed and female non-player characters raped for sport.”5 Given that even canonical game theorists such as Fine seem unconcerned with the reproduction of rape culture within the space of role-playing games, it is important to better understand the history of racist and misogynist attitudes in game culture. This essay addresses this problem by offering a close read of two articles on the topic from The Dragon, TSR Hobbies’ flagship magazine for all things Dungeons & Dragons. Unlike Jon Peterson’s recent essay, “The First Female Gamers,” which argues that TSR Hobbies was instrumental in bringing women into the hobby, this essay concerns the unfortunate amount of currency still afforded to misogynist attitudes in the gaming community. It proposes that these attitudes reproduce themselves by way of the community privileging the accuracy of simulation over the ethics of simulation.

The first article reviewed in this essay is “Notes on Women & Magic – Bringing the Distaff Gamer into D&D,”6 which offers a schematic for the ways in which the female body should be understood and regulated within Dungeons & Dragons. The second article, “Weights & Measures, Physical Appearance and Why Males are Stronger than Females; in D&D,”7 also deals with the schematization of bodies, but deals more specifically with how characters look when role-played. Together, the articles offer a glimpse of game culture in years 1976 and 1977. Regarding audience, these articles were published for men and by men. Although The Dragon operated on a publication model that openly accepted articles by any contributors, women were infrequent contributors in the early years.8. The two essays analyzed in this article offer clues toward understanding the poisonous trends of racism and sexism within the hobby.

Len Lakofka, author of “Notes on Women & Magic,” was an avid participant in the play-by-mail Diplomacy community. Most notably, Lakofka served as the vice-president of the International Federation of Wargamers in 1968 when they sponsored the first Gen Con convention. Later, Lakofka would take on a stronger role in organizing the convention, organizing most of it in 19709. In the 1970s, Lakofka was responsible for playtesting many Dungeons & Dragons supplements and, in fact, advised Gary Gygax on many design decisions made over the course of the game’s development. Lakofka was an important figure in the history of Dungeons & Dragons, and although many of the rules proposed in “Notes on Women & Magic” failed to stick10, they do offer an interesting historical lens through which the culture of the time can be interpreted. Specifically, they allow us to understand the ways in which a predominantly white male gaming community imagined the bodies of women.

Needless to say, women were not the intended audience of The Dragon. This is made abundantly clear in the antagonistic and condescending tone Lakofka takes in “Notes on Women & Magic.” As the essay begins, one must wonder whether the notes were staged as a manifesto of whether or not women should be allowed at the game table, or within game worlds more broadly. Lakofka writes:

There will be four major groups in which women may enter. They may be FIGHTERS, MAGIC USERS, THIEVES and CLERICS. They may progress to the level of men in the area of magic and, in some ways, surpass men as thieves. Elven women may rise especially to high levels in clerics to the elves. Only as fighters are women clearly behind men in all cases but even they have attributes that their male counterparts do not!11

Despite the clearly sexist language employed in this article (where Lakofka allows women to participate in game fictions through his use of the word “may”), Lakofka makes an earnest effort toward offering a workable simulation of the female body for interested players.

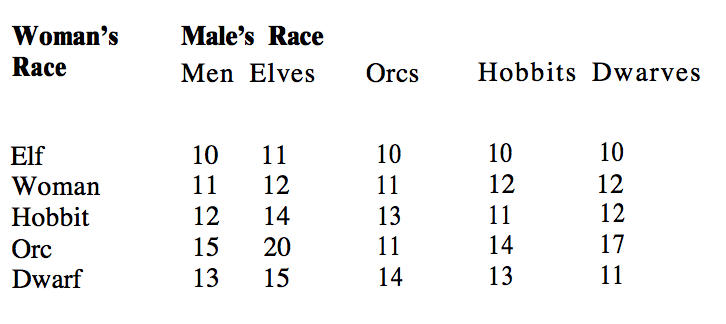

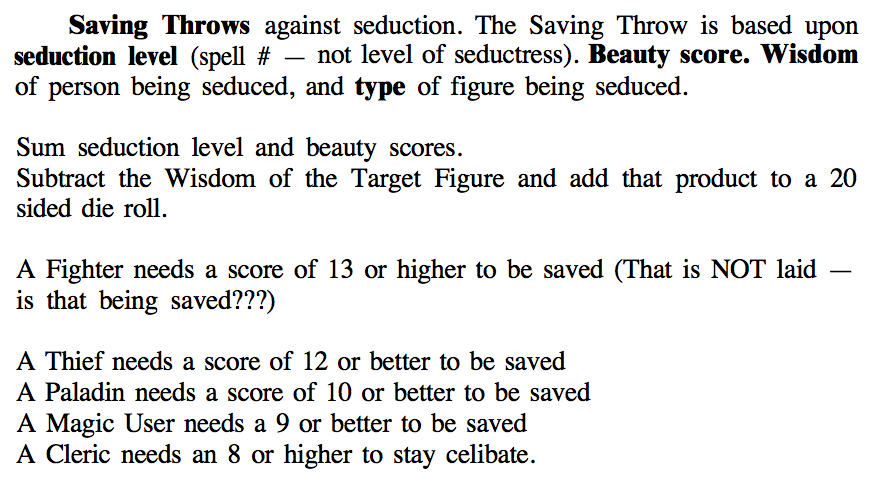

The key difference between the male and the female body, according to Lakofka is that instead of a charisma score, women have a “beauty” characteristic. This statistic, unlike charisma (which has become a standard statistic in role-playing games), has a range of 2-20 as opposed to 3-18, and is relied on for a number of special skills that only female characters can use during the play of the game. These abilities focus on the character’s beauty specifically, and consist of abilities such as “Charm men,” “Charm humanoid monster,” “Seduction,” “Horrid Beauty,” and “Worship.” As shown in Figure 1, some of these abilities could be used to charm men of various races provided the female’s beauty score was equal to or higher than the number shown on the chart. Additionally, Figure 2 shows the ways in which characters can opt to roll a die in protest in order to resist seduction. These abilities represent a woman who uses beauty as a weapon to get what she desires from men who must in turn resist succumbing to temptation. Not only do these statistics reinforce the stereotype that a woman’s value and power lie only in her beauty, but they also reify a heteronormative standard of sexuality where relationships are exclusively staged between men and women. Finally, Figure 1 can even be read as a schema of discrimination wherein I argue that the slight and fair builds of Elves are preferable to the plump and ruddy Dwarven build, or to the dark, muscular build of the Orc12.Thus, these charts work to reinforce racial stereotypes that revere a pale and slight standard of beauty; one that prefers exotic “oriental”13 bodies and reads black bodies as invisible.

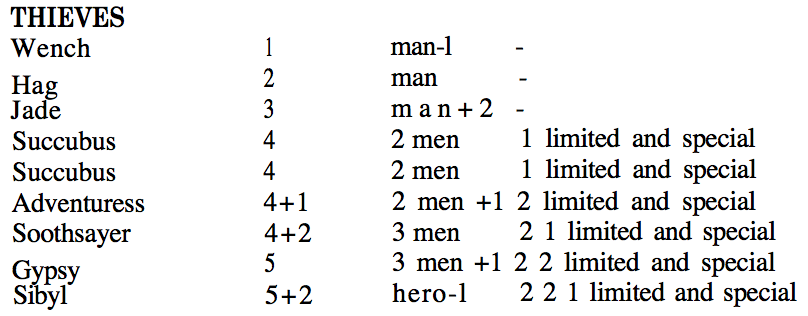

In addition, Lakofka presents tables that elaborate on the abilities of women engaging in combat. Here, women are compared to men via the “default” standard of fighting prowess. Statistically speaking, Lakofka works to show the ways in which women fight at a disadvantage to men in a variety of contexts. A level one thief, titled “wench,” fights at the ability of “man-1,” while a level two thief, titled “hag,” fights equivalently to a “man.” Even a level one fighter advances at a disadvantage, fighting only at the strength of “man+1” upon reaching level two (See Figure 3). Lakofka justifies this by explaining that it is easier for women to advance in levels, and so they fight at a drawback as they progress. Still, as evidenced in his introduction, fighting women may only advance to a maximum of tenth level, regardless of their tenacious advancement. As a whole, the system makes a consistent point: the bodies of women can only be understood when set in opposition to those of men, and within this realm they excel in abilities which foreground the importance of their beauty.

In contrast, P.M. Crabaugh’s article, “Weights & Measures, Physical Appearance and Why Males are Stronger than Females; in D&D,” offers a more precise take on the configuration and abilities of bodies. It focuses specifically on the ability of bodies to lift, measures of height and weight, and the cultural parameter of ethnicity. Crabaugh saw the bodies of women in a different way, and saw female bodies as superior to male bodies in a variety of ways (aside from sheer strength), granting female player characters a +1 bonus to their constitution statistic and a +2 bonus to their dexterity. He also offers a defense to those in the community who might beg to differ:

[Constitution and Dexterity] and body mass are the only differences between male and female. Before someone throws a brick let me explain. As Jacob Bronowski14 pointed out, as well as, no doubt, many others, there is remarkably little difference between male and female humans (the term is here extended to include the Kindred Races), compared to the rest of the animal kingdom. There is little physiological difference, no psychological difference (Think about it. Consider that human societies have been both matriarchies and patriarchies. Don’t let your own experience blind you to history.), and so forth15.

He then goes to offer the point that a constitution bonus is due to the fact that women are more resilient to disease than men, and that the dexterity bonus hails from the fact that women have lighter builds, with slighter fingers, and that they are then therefore more adept at picking locks than others.

Although not as condescending as Lakofka’s treatise on women, Crabaugh reveals in his writing an essentialism that reads bodies as purely biological entities. By this, I mean to say that – for Crabaugh– knowledge of the body could be and was apparently ascertained through strictly “scientific” measures. Michel Foucault calls such a reduction of bodies to numbers a mode of informatic power, primarily used to manage and control bodies in the modern state16. Within Crabaugh’s writing (and within Dungeons & Dragons as an entire game system, which views bodies as assemblages of strength, dexterity, constitution, wisdom, intelligence, and charisma statistics) we can read this as a means of controlling bodies in the game state, but also, more broadly, a reification of existing modes of state and scientific control within the game state.

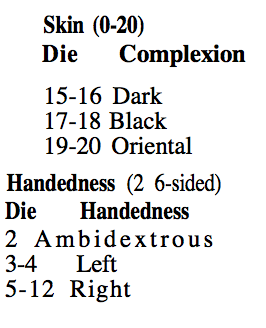

Alongside “handedness” in Crabaugh’s tables, lies “Skin” (Figure 4). According to this table, roughly one tenth of all players should have a “dark” complexion, one tenth of all players should have a “black” complexion, and one tenth of all players should have an “oriental” complexion. In defense of his chart, Crabaugh immediately explains that these determinations stem from representations in the literature that players drew on for play: “The reason that 16 out of 20 possibilities are variations on caucasion [sic] is not that I think that that represents the actual population-distribution; it is because the literature of swords & sorcery is primarily (but not entirely) concerned with Caucasians.”17 Here we find representation functioning as a mode of power that replicates and reifies. The representational contexts and normativities traditionally valued by members of the community are replicated and reinforced here within the systematic logic of the game (where it might replicate then, again).

The problem that recurs in both of these historic examples of game systems is one that elevates the ideology of simulation above values of inclusivity, plurality, and compassion. Such pursuits of authentic recreations and representations of past histories (such as in historical reenactments) can be problematic for the ways in which they offer an airtight alibi for the reproduction of predominantly white, male, historical vignettes. But Crabaugh and Lakofka move this attitude regarding authenticity and simulation into worlds of fantasy where the alibi is lost (no longer is the reenactment about history). But here, again, an opportunity to establish gender equity was lost, owing to the racist, misogynistic, and homophobic trappings of that particular genre of literature. For instance, Robert E. Howard, author of Conan the Barbarian, though idolized by the fan communities engaged in Dungeons & Dragons, has also been heavily critiqued for themes of white supremacy in his work. To simulate fantasy in the 1970s was to simulate work that divides people between good and evil, depicts a world filled with predominantly white male heroes, and often holds that might makes right.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z3kBWP231hI

Disappointingly, the scene has changed very little in the past 47 years. In George’s 2014 essay regarding the lack of diversity at Gen Con, he touchingly writes: “As an awkward teen, like other awkward teens, I wanted to be accepted. But acceptance meant something different to me, as perhaps it does to other minority teens. Acceptance meant being white.”18 With that in mind, it is interesting to note Lakofka’s historic intersection with Gen Con, as both attendee and organizer in the early years. We must ask whether Gen Con and other related community events have ever been particularly free of problematic racist and misogynist tropes. To some extent, the hobby has been coping with these biases since its infancy, and they are a seemingly inextricable part of the rules and cultural traditions that have been passed between players for years.

The simulation of literature, imagination, and other fantastic worlds, however, is not without potential for improving representation and inclusion. Although several toxic pathologies (specifically racism and misogyny) can be traced through the genealogical work above, players, designers, and gamewrights alike can choose to represent whatever they like when playing games in the future. Though some game rules are cemented in print, the culture of the hobby also allows games to bring with them an interpretive flexibility where rules can be broken, statistics can be changed, different bodies can be designed, and new worlds can be represented. This task is one that must be taken up by all members of the community. It means not considering these discussions as solely for “social justice warriors,” it means acknowledging that extreme biases are written into the games we play, and it means taking deliberate steps to avoid reproducing rules and images in games that play host to a problematic politics of representation.

–

Featured image CC BY-NC-SA, “Leaf Elf, by Guido Veltmaat.

–

Aaron Trammell is a Doctoral Candidate at the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information. He is also a blogger, board game designer, and musician. He is the multimedia editor of the Sound Studies blog Sounding Out! For his dissertation he is investigating the ways that fan subcultures in the 1960s created the game Dungeons and Dragons. In particular, the importance of affective bonds to their work, and the influence of Cold War motifs on their writing. You can learn more about Aaron and his work at aarontrammell.com.

An excellent piece. One minor quibble, and one broader point:

The quibble: you mention Lakofka’s patronizing use of “may” in that women “may be FIGHTERS, MAGIC-USERS, CLERICS, and THIEVES.” If you read the really early D&D stuff, particularly the edition published circa 1974 and the early issues of “The Dragon” (later retitled “Dragon”) magazine, they were *full* of weird permissive verb uses like that. Given the rest of Lakofka’s article, it’s entirely possible that he was being condescending here, but it’s the same language regularly employed at the time when talking about men too.

The broader point I’d like to make is, nonsensical pseudo-science aside, the main argument toward “othering” women (and other races) is that the source fiction, mainly pulps but also much older material, has almost always treated women as the other. If your inspiration is sexist, a truly faithful homage is going to be sexist as well.

An interesting point not mentioned so far: Greg Stafford’s amazing RPG “King Arthur Pendragon,” published in 1985 and still in print in various forms, which allows for women to be knights just like any male character, but (at least originally) treated women as a completely separate “character class” with wholly different rules. “Pendragon” is, on the whole, an excellent game design and I’ve had a lot of fun with it, but that is some seriously troubling stuff. On the other hand, it’s absolutely faithful to the sexist source material (which, one imagines, reflected contemporary sexism).

So then the question becomes, what does it say about RPG players, that we dig on this sexist source material?

Lord knows there’s tons of source material, especially in the pulps, that regards Africans, and African-Americans, as being deeply, deeply Other, but the idea that there should be special rules for playing Nubian characters in D&D, for example, has been routinely rejected by nearly all tabletop gamers. But the contrasting idea that sexist source fiction (or historical accuracy) deserves a certain degree of respect, seems harder to root out.

Thanks, James! Really welcome feedback, and an excellent question.

To your quibble, that’s a good point. I would simply say that the proof is in the pudding here. Very few women wrote for The Dragon the first few years, and even if it wasn’t the tone of the article, I wouldn’t be surprised if it was the content of the article. There is a great article by Kim Mohan in Dragon #39 where these issues are faced head on, but until that point, sexism abounds! So I would say that my article could have just as easily been about Jon Pickens’ article, “D&D OPTION: ORGIES, INC.” in The Dragon #10. Here it is suggested that DMs use orgies as a way to get players to spend money they are hording by enticing them to indulge in “wine, women, and song.” (p.5) There are plenty other examples by many authors of “othering” language, too. I know that this may not have been condoned as “official” material, but it was published by TSR Hobbies official magazine. And, I would add, it certainly does not constitute a friendly environment for women.

Regarding your question, “what does it say about RPG players, that we dig on this sexist source material?” You got me, but that’s the point isn’t it?

As long as we can reflect critically on the ways that we replicate problematic attitudes in our games, I think we’re moving in the right direction. Only if we reflect on these things can we take steps to make sure that our culture will grow in a healthy and inclusive way.

It’s not that my article cited above argued that TSR intentionally brought women into the gaming hobby – D&D accidentally opened the door to women. Our fragmentary evidence suggests that previously, the gaming community was only 0.5% female, but D&D unexpectedly attracted a customer base of fantasy fans which included a vastly greater percentage of women. Several early RPG designers thus hurriedly proposed game systems intended to include women explicitly. I believe these people were virtually all well-intentioned, even if their work seems almost comically misogynist to us four decades later.

And yes, as we see above, Len Lakoka went very wrong with this. But showing that in isolation misses the real lesson: his proposal got the kind of pushback you get when you go very wrong. He was roundly condemned, and the editor of the Dragon basically retracted the article (calling it non-canonical and “sexist”). Lakofka’s portrayal was not something the gaming community condoned, or even tolerated – it was the sort of thing that could get you hung in effigy, as my article shows. Presenting this without the context that came before and after Lakofka’s article gives the distorted sense that it was representative of designers’ or the community’s stance towards “women’s bodies.” The hobby was at the time still an overwhelmingly male community struggling with inclusivity, but these early, clumsy attempts to provide for “women gamers” were glimmers of progress, if only as teachable moments, and severing them from the popular reaction exaggerates their influence and importance.

Thanks for the feedback, Jon! Lets be clear on one thing here, I presented your article as a context for this case study in the first paragraph, and although we come to different conclusions, I agree that context is extremely important in this case.

Now, to your point here, I would ask why women in the hobby needed the door opened for them in the first place? If the community was full of well-meaning individuals, as you claim, I would imagine that there would have been no issue. Further, my argument is not that the individuals involved had bad intentions, it is, instead, that they didn’t have their priorities straight. They were, in many cases, more interested in offering what they considered accurate simulations than producing an equitable community. That well-meaning mistake is what produces a toxic environment.

To your second point, that Lakofka’s article was resisted by some portions of the community, we agree. But, again, I draw a different conclusion. First, I am curious as to why the editor of The Dragon printed the article in the first place if they felt it was racist and sexist? I persist that there was a culture of misogyny in the community that made such articles and opinions normative. I’m sure Tim Kask (the editor) meant well, but was blind to his own cultural norms, and because of that allowed the magazine to reproduce a problematic article. Their later retraction, although commendable, smacks of a corporation talking outside of both sides of its mouth. Once TSR Hobbies realized that women were valuable as consumers, they worked to be as inclusive as possible. It would be a public relations nightmare to back articles such as Lakofka’s.

Finally, in your article you reproduce an image from Alarum’s and Excursions #19 that depicts Lakofka, Kask, and Gygax being hung by a group of women gamers. If the status-quo of gaming for women at the time was hunky-dory, I don’t think such a strong and incisive image would have been drawn. Rather, I feel that it indicates the degree of oppression felt by women in the community at the time. It is a clear and outspoken form of resistance that makes clear the degree to which this was a problem.

Furthermore, this wasn’t just a problem for the Dungeons & Dragons community, it was also a problem for the Diplomacy community which published in many of the same fanzines. Penelope Naughton Dickens was particularly outspoken at the time about the sexist nonsense that she had to put up with in her corner of the gaming community. You can read about many of these issues in The Pouch.

There’s always one more side to a story. And although you offer some great evidence that helps us to understand the culture of the time, it doesn’t invalidate these points. There was, and still is, a problem of inclusivity in the community. Let’s be clear on that.

Thanks for sharing!

No one is going to argue that there was not a problem of inclusivity in the community then, nor that there aren’t problems today. My pushback is against the specific claim that the “toxic pathologies” of the gaming community can be “traced” to Lakofka’s piece, which depends on the further claims that Lakofka spoke for TSR and influenced inclusivity at Gen Con. I don’t think any of those claims are historically viable.

You cannot assess the impact that an article had on female participation and inclusivity through a “close reading” of the text of the article alone. Rather than seeing evidence that women were put off from D&D by Lakofka’s proposal, both men and women both pushed back against it as sexist, and its ideas were ignored and unceremoniously buried under a rock. There is no reflection of them in the Players Handbook or other official rulebooks TSR produced. Following the publication of this article, we do not see a decline in female participation in gaming – on the contrary, in this period, female participation was increasingly rapidly by the metrics we can follow. So what exactly is there to trace, other than that a dead-end article was rejected by the community and forgotten by all but the archivists like us? For me, the teachable moment that it created was a huge step forward in inclusivity. I have trouble understanding why you want to downplay that and instead puff up this Lakofka paper tiger.

You are right to ask why Kask printed this article in the first place. I think the key answer is that no one at the time had any idea what including women in the gaming hobby should look like. Yes, with forty years of hindsight the answer seems clearer to us, or at least we know a lot of things that have been tried but didn’t work. But look at the structure of the SCA in 1970s, say, which had strong female leadership and participation but also extremely stereotypical gender roles (like, male knights fight for the honor of ladies who sit on the sidelines). Was the SCA misogynist, for adopting that structure – was it more or less inclusive than D&D then? I largely agree with your assessment that Lakofka unfortunately drew on sword-and-sorcery fiction for this account of women, to disastrous effect. I can’t however agree with your assessment that Lakofka’s views represented the “status quo.” Pretty much by definition, you don’t get hung in effigy for expressing views that are the status quo. And moreover, we have access to the historical record, where we can see other views expressed about women, and conclude that Lakofka’s piece was an outlier. The Dungeoneer article got much milder pushback, for example, as it was less of a travesty. But it was trial and error then, this was all uncharted territory.

I’m surprised you’d ask “why women in the hobby needed the door opened?” The answer must be the same as it was for many other spheres of society: in order to overcome pre-existing gender biases of various shapes and sizes, something no amount of meaning well reverses. Yes, there was sexism, but what you neglect here is how the gaming community around this time began to measure female participation and address how to rectify its problems: SPI hiring female designers, for example, as would TSR. You are certainly right that TSR made the decision to include text for women in D&D when women started playing D&D – that is indeed a big punchline of my article. But given how the industry actively worked to increase its inclusivity, I guess I don’t find the practice of tuning products to women an oppressive or necessarily cynical one. To me it looks like recognition and progress – maybe it wasn’t much, but it was a start, perhaps even literally the start, when it came to gaming. The road was bumpy then, and still is now, but before D&D, there was no road. Cherry-picking a widely-reviled dead-end article and treating it as a “historical lens through which the culture of the time can be interpreted” unsurprisingly neglects what was actually going on in the culture of the time.

Jon, I’m not a positivist historian, and so I don’t accept the claim that there is a singular historical truth that we can read from documents. Documents tell a number of different stories, and so I choose to highlight stories which vocalize moments of struggle and discord in order to elaborate on moments of ideological contest.

This article was a short close reading that I felt highlighted some degree of intellectual contest in the community at the time, and so it is not comprehensive. As I pointed out, much of the background information at this time can be gleaned from your write-up, which does, in fact, support many of the conclusions I draw here. To claim that it is “ahistorical,” however, is condescending and inaccurate. I rely on documents housed in public archives and forums to inform this work, and so I can only speak to the way these struggles present themselves as a matter of public discourse.

So the big point in question you raise here is the degree to which Lakofka had an influence over the product, Dungeons & Dragons. You argue that he was a second tier player. Regardless of whether he was or not (can you provide a source for this claim?), we still see Jean Wells and Kim Mohan discussing the very same issue in Dragon #39. They even acknowledge that, “Then there is the D&D or AD&D game system itself. Another often-heard complain from women concerns the built-in restrictions on maximum strength for female player characters. It does seem unfair to many women that human female characters cannot have Strength of more than 18/50, when men can attain 18/00. However, the reason for this is based in reality and cannot logically be argued against. Women are, as a group, less muscular than men, and although some women may indeed be stronger than some men (as in real life), the strongest of men will always be more powerful than the strongest of women.”

I’m not sure what you want to define as a historically relevant idea, but when the very same modes of simulationist discourse are still popping in a magazine thirty-six issues after their initial publication, I would hesitate to describe an article as an outlier. And I certainly wouldn’t claim it was ahistorical.

I understand why you see this as cherry-picking, but I beg to differ. Cherry picking assumes that there was no actual controversy, and as you’ve shown in your article, the pushback in Alarums and Excursions shows that there was. The replication of these ideas in The Dungeoneer shows that there was. The return to the topic (and mechanics) in Dragon #39 shows that Lakofka’s article had an impact.

We are talking past each other, I fear, in so far as I am pushing back against a very specific claim and you are countering by speaking to a much more general and uncontroversial point.

Of course there were then and are still now manifestations of sexism in D&D and its community. Pointing to Wells and Mohan’s article in Dragon #39 illustrates that point handily. However, their article does not refer to Lakofka or his “Women and Magic” system, either by name or by implicit reference. Your article stipulates, again, that certain “toxic pathologies” can be “traced” back to Lakofka’s article and his person, through his influence over TSR and Gen Con. I see no evidence that those specific linkages exist.

If Wells and Mohan were complaining about women’s strength being restricted to 2-14, or having a Beauty stat in place of Charisma, or the implications of the “Charm Man” and “Seduction” spells, then I would be very sympathetic to an argument that you could “trace” those specific later pathologies back to Lakofka’s “Women and Magic.” But the 18/50 strength limit for female characters in the Players Handbook is not from Lakofka’s article. Yes, it is an example of the simulation-driven sexism that is your primary concern (and yeah, it belies Gygax’s promise that there “be no baseless limits on female strength”), but I would deem it a very different and far less offensive stipulation than Lakofka’s reinvention of female adventurers as those whose power is largely realized through seducing men. Wells and Mohan in fact defend a strength cap, even if they think 18/75 might be a better one. The Players Handbook has its problems, but it is worlds better than Lakofka’s system from an inclusivity perspective (and compared to other systems of the time, like say Chivalry & Sorcery). So where is the evidence that the 18/50 strength cap has anything to do with Lakofka whatsoever? Similarly, claiming that the Dungeoneer piece replicates “these ideas” makes me wonder which ideas you mean, since the Dungeoneer keeps Charisma, doesn’t cap female strength at 14, and doesn’t propose “Seduction” as the most powerful spell ability of female characters. If “these ideas” encompasses any form of system difference in the representation of males and females, I think you are conflating some really horrible ideas with some ideas that are merely bad and possibly with some ideas that actually aren’t sexist at all, but what you are not doing is convincingly “tracing” anything.

In a comment below this one, I already provided some reasons to think that Lakofka did not exactly nourish Gen Con, and why he was distanced from Gygax in the formative years of TSR. If you want a cite, I might start with p55-56 of PatW, where I quote Lakofka’s unwillingness to run the 1972 Gen Con. To be clear, I’m not here arguing this to defend Lakofka personally or his preposterous ideas. I’m doing this because you are presenting the supposed influence of Lakofka’s article and person as evidence that his misogynist views were the “status quo” for TSR, for Gen Con, and for the gaming community. This is a claim that requires very different evidence to support than what you are presenting. In fact, the tenor of the community at the time when Lakofka wrote this was one of rising inclusivity and incremental improvement, and the views in “Women and Magic” were far from the status quo. They got you hung in effigy.

Okay, I think we’re getting somewhere with this, finally. Let me address your point of historical trace.

We’re looking at this word in two radically different ways, I think. From your read of my article, you feel that I’m arguing that we can “trace” all of the misogyny in the game community back to TSR Hobbies, and therefore Lakofka. If that were my perspective, I would agree that it is almost a comical and ahistorical argument. But this is not my perspective, or my argument. I don’t think Lakofka’s article was some kind of pandora’s box corrupting everything near it, instead I think it’s a strong example of how misogyny worked at the time in the community. And one which bears a remarkable resemblance to the ways misogyny still functions in the community today.

Okay, so you’re about to inquire why I would claim it was pathological, or even use the word trace if I wasn’t discussing a causal path of circumstances? Well, the answer is that I do still believe this is a pathological problem that occurs on a systemic level in the community. And, to trace it, we all must work together to delineate specific points of articulation where it occurs in the community discourse. My article is a step toward this goal, but it is a relatively small step. That’s why the Wells and Mohan article is important, as is the Dungeoneer write-up. But, I acquiesce to your point that these forms of articulation were not carbon-copy reiterations. It does mean, though, that we see a pattern recurring in the discourse. One which articulates a particular discussion around how bodies aught to be represented in games.

So, finally, back to the wiggly point of Lakofka’s involvement. You’ve provided ample evidence to show that he wasn’t part of the TSR Hobbies crew, and it is sound. But, regardless of how the internal politics played out between TSR and Lakofka, the image from A&E #19 depicts three names: Gygax, Kask, and Lakofka. This means that the fans of the time did see them all as running in the same circles, and having an influence on the same product despite the best efforts of Kask and Gygax to distance themselves from Lakofka’s article. As you point out, Lakofka’s misogyny could get you hung in effigy, and it is pretty clear where the rising progressive tide of gamers placed the blame.

I speak to the point about misogyny in the overall gaming community both then and now because it is far from uncontroversial. And although through today’s lens now we can read Lakofka’s article as almost comically hateful, I am positive that similar things will be said in the future about the recent dustups in today’s community. It’s important that we recognize these mistakes and the extent to which they are still embedded in today’s discourse.

Although women are no longer forced to work with an amalgam of inferior statistics for their characters, as Sarkeesian has pointed out in her infamous series, they are still objectified for their “beauty” time and time again in games. No, Lakofka didn’t produce this discourse, it has existed aeons before he was born, but his article marks a specific point of articulation in the history of role-playing games. And, at the time, his article was seemingly “well-meaning” enough to have been published by TSR Hobbies. That for me says a lot about the cultural norms of the time, and the sorts of attitudes that were taken for granted in the community. We can disagree here as to whether or not this constitutes a “status-quo.”

An important discussion to save for another time. Thanks for the thorough and detailed feedback!

It is possible from the Grognardia interview to get a bit of the wrong impression about Lakofka’s association with TSR and Gen Con. Gen Con was Gary Gygax’s baby, and even before D&D came out, Gygax and Lakofka had a falling out in part because Lakofka was trying to prop up a competing Chicago convention. One year (1972) when Gygax could not run Gen Con himself, Lakofka refused to run it or support it due to his commitments to his other event. It is thus a bit of a stretch to connect any inclusivity problems at Gen Con with Lakofka: he didn’t exactly place his stamp on the convention. Similarly, Lakofka had little influence on TSR in its formative years for much the same reason, that he wasn’t at the time in Gygax’s confidence. Lakofka did however have some input into AD&D, as he gets a nod in the beginning of the Players Handbook – which, as my article shows, has pretty much the most inclusive text of any game at the time.

I’m mostly a fly on the wall here, but I’d like to share a personal anecdote from my mother:

“We should have a conversation about Dungeons and Dragons some time… It seems we are looking at things through different sets of glasses, mine are from the 70’s. D and D wasn’t any different than Parchesi, Monopoly… It was just more creative, more imaginative. It was an opportunity for young people, BOTH sexes, to gather and have fun. The only reason I didn’t get involved, as you know, was that I don’t like games. But I never felt it was a game for males only…. How it evolved into a predominantly male-dominated game might be a journey to follow. And marketing?!? If there was marketing at the time, who saw it?!! No internet. D and D was spread by word-of-mouth…”

That’s her impression, anyway. But it may be helpful to look at pre-moral-panic D&D (70s) and post moral-panic D&D (mid-80s) as mildly differentiated epochs?

Have to agree with Evan. I mean sure,back in the early days perhaps D &D did seem to cater a bit more to men & boys. But it attracted women to it too and noone ever tried to keep women out. As they say, “Noone is fond of a 100% sausage fest” and female rpgers usually ad their own special spark to a campaign.

To say D & D ever attempted “women-hate” is just too much for me. Perhaps females had to endure sexy depictions of fantasy women on books and in magazines related to the hobby but just as many women want to actually play as attractive characters too. (That and there was plenty of Conan-esque beef-cake to go around too)

Remember without D & D we wouldn’t also have White Wolf’s world of darkness, a sophisticated fun campaign setting that is woman friendly enough to include a feminist werewolf clan (Black Furies) and sessions that focus just as much on socializing and politics as they do on combat.

It is a good article, but I would like to point out something to be fair. Some of the portrayal of women in early roleplaying stems from how women often wish to be portrayed. Not all women of course, but I have noticed (especially among those who have body issues) that they always search the internet to find scantily clad women to be their avatar or the picture of their character. Roughly two out of three of the women that I have ever GMed for do this unashamed.

The images in the player’s handbook (especially the heavily armored woman) are a great indication of how far we have come, but I still think that for as long as people want to be something they are not that the sight of “bikini babes” in fantasy will remain.

Thanks for reading, Charles!

There is a great article by Jean Wells and Kim Mohan in Dragon #39 entitled “Women Want Equality: and why not?” that delves into these issues with a more even hand. I would argue that it even marks a turning point for TSR Hobbies as a corporation. Here two conflicting stories are related:

1) The struggles women faced when being forced into one of many stereotypical, and often misogynist roles: “Women who play female characters must be concerned about their characters becoming pregnant, or about their characters being ‘used’ as sex objects to further the ends of a male-dominated party of adventurers.

One reader, Sharon Anne Fortier, related a story about a female dwarf character of hers that was forced by the males in the party to seduce a small band of dwarves so that the party could get the drop on them and kill them.”

2) The other narrative is more positive, and centers around enjoying the ways that RPGs allow for a sense of empowerment: “The other side of this coin is that female players do enjoy having their characters flirt with male characters and NPCs, showing a personality they might be too shy or afraid to display in real life. One reader pointed out that playing a female character allows her to do thing she things would be fun, but would never try to do in real life — like wearing a low-cut dress and bending down to brush some dirt off her ankle while watching the reactions of the men around her.”

The point is that while the game holds a tremendous opportunity to allow folks the agency to experiment with their bodies and psyches in new and exciting ways, some gaming groups would typecast women in the hobby. And, in those moments, it becomes less a dialogue about empowerment, and more of a dialogue about oppression. Feminism is less about what kind of clothes someone chooses to wear and more about why it’s important that we have the space to be different and choose our own clothes.

Finally, back to my key point, regarding the politics of simulation. Even though Wells and Mohan were pretty fair in their article, they still fall back on the exact biological essentialisms that plagued Lakofka’s article: “Then there is the D&D or AD&D game system itself. Another often-heard complain from women concerns the built-in restrictions on maximum strength for female player characters. It does seem unfair to many women that human female characters cannot have Strength of more than 18/50, when men can attain 18/00. However, the reason for this is based in reality and cannot logically be argued against. Women are, as a group, less muscular than men, and although some women may indeed be stronger than some men (as in real life), the strongest of men will always be more powerful than the strongest of women.”

The problem is that discrimination through simulation seemed to many players, designers, and writers at the time to be a “logical” and fair design decision. It is through this very line of argumentation that discrimination still takes place as people like Zoe Quinn are held to a set of purportedly “logical” standards by a community with a clear ideological bias.

We have come a long way, but there are still many who would say that the community is still working out some major issues around inclusivity. Please see Kessock and George’s articles if you would like to read more about that.

Thanks for chiming in!

(For some reason I no longer have a reply button in the thread above…)

Sure, we’re close enough to the same page that we can leave this to discuss sometime over a beer (maybe a club soda, actually). But I do insist that in order for Lakoka’s article to be accepted as “a strong example of how misogyny worked at the time in the community,” we would need some evidence that the community did anything with the idea at the time other than reject and disown it. Without that, it is instead a strong example of how this expression of misogyny was unacceptable at the time in the community. You can argue that merely airing the proposal was problematic, and there’s some merit in that view, but (per my SCA example) that’s a much easier judgment to make in hindsight than it was at the dawn of gaming inclusivity.

[Threads cut off after 6 posts for aesthetic reasons. Continuing here is fine.]

I wouldn’t argue that there has ever been a dawn of gaming inclusivity. Women played games long before there was Dungeons & Dragons. But that’s not your point, you want to locate the dawning of equity within the RPG community. To that I would just say that I feel that it is still in flux and struggle and that 10% participation was a pretty sorry number.

I’ve mounted evidence of where Lakofkas idea pops up again and again, and how TSR Hobbies continued to publish misogynist essays such as “Orgies Inc.” in The Dragon #10. But not just that, you can open any issue of The Dragon and read almost any article at that time to get a feel for the contours of sexism in the culture. They’re abundant. Let’s not ignore them, even if there is also good evidence which shows that not all in the culture approved.

Aaron, man, I wish I wasn’t writing this, I was really planning to be done. But I just can’t let it stand that “Lakofka’s ideas” are what we see popping up in the Jon Pickens article in Dragon #10. Yes, that article has a provocative title – but its actual contents are strategies for a DM to rid wealthy PCs of excess cash. It suggests numerous things unrelated to orgies, including, say, philanthropy. But in the one paragraph out of twenty-five or so that delivers on the promise to discuss orgies (okay, Appendix II does describe the depletion of psionic powers through orgies too), we find a single sentence listing “wine, women and song,” and in it an implication that money can be spent on those three things. Nowhere else does the article mention or allude to women.

Really? Is this “Lakofka’s ideas” returning from the grave to haunt us? How is the implication that it is possible to spend money on women, even read in its least generous sense to connote outright prostitution, how is that in any way related to Lakofka’s proposal to limit the powers of female characters to a sexist travesty? I can’t see how anyone could walk away from reading that article with this impression.

Honestly, I think there are merits to the argument you are trying to make about the ethics vs. accuracy of simulation, but grasping at straws like this to try to prop up Lakofka’s influence does not bolster that argument. I totally concede that are other places to find sexism in the Dragon and other contemporary periodicals, and I wouldn’t be here writing this if you were making that claim without then adding that you have “mounted evidence that Lakofka’s idea pops up again and again.” I must respond that the Pickens article demonstrates nothing of the kind.

And yes, of course 10% is a sorry number. It’s just a much better number than 0.5%, which is what the gaming community (as I define it in my article) had prior to D&D. The path from 0.5% in 1974 to 10% in 1979 has a lot of bumps in it, including one in 1976. Today, gaming is vastly more diverse, and both in spite of that and perhaps because of it, we have a different set of inclusivity problems than people did in the 1970s, which leaves us still a long way from where we should be. My personal interest is in both celebrating the pioneering female gamers (who have been utterly neglected, in my estimation) and showing the statistically-evidenced role that D&D played in getting those first women included. I’m not sure how I could walk away from your version of this story with any other impression than that D&D actively excluded women from the hobby.

Fortunately, Jon, there’s not much to debate here. I think you misunderstood my sentence: “I’ve mounted evidence of where Lakofkas idea pops up again and again, and how TSR Hobbies continued to publish misogynist essays such as “Orgies Inc.”” The mounted evidence I refer to is “Those Lovely Ladies,” in Dungeoneer and “Women Want Equality,” in Dragon. “Orgies Inc.” was more or less a shorthand to refer to the subtle acts of misogyny that TSR would routinely publish.

I am glad that you are giving voice to women in gaming who faced systemic oppression in the 1970s. I’m trying to better articulate how that oppression functioned in seemingly mundane documents. In that sense, these two articles compliment one another quite nicely.

Okay, I took your conjunction there differently than you apparently intended. Even if you reduce this to locating simple misogyny, Pickens isn’t the most convincing example – we haven’t talked at all about art, but I could see an argument that the art accompanying the Pickens piece is way more problematic than the sentiment we can infer from that one sentence . And I would of course concede that the “Those Lovely Ladies” article does at least mention Lakofka’s ideas (to say that it’s going to propose something different), even if the Wells/Mohan article does not.

I do want to get to a place where we are arguing complimentary perspectives on the same source material, and I don’t think that’s out of reach. But perhaps best pursued when we can spend some face-time hashing it out.

The Wells/Mohan article, though quite progressive itself, accepts that a strength handicap might still be appropriate for female characters (as long as it is counterbalanced in other areas). I’m not saying that this idea began with Lakofka, but I am saying that you can see an idea regarding how bodies are statistically constructed replicating in Lakofka’s piece, The Wells/Mohan article, and other sources. My emphasis is on how ideas, themselves, replicate, not on who did the replicating.

I agree, though, that we ought to take this offline for now. Until next time.

It is a good article, but I would like to point out something to be fair. Some of the portrayal of women in early roleplaying stems from how women often wish to be portrayed. Not all women of course, but I have noticed (especially among those who have body issues) that they always search the internet to find scantily clad women to be their avatar or the picture of their character. Roughly two out of three of the women that I have ever GMed for do this unashamed.

The images in the player’s handbook (especially the heavily armored woman) are a great indication of how far we have come, but I still think that for as long as people want to be something they are not that the sight of “bikini babes” in fantasy will remain.

Really great article! I am a student of anthropology and I am conducting a feminist ethnography on D&D and your article has some really awesome points that are going to bolster my participant observation immensely. The comment section will be very useful as well.

I also would like to throw in my little two cents here. Every human civilization is completely dependent on its culture. Every cultural product we create has our beliefs, values, norms, and ideals stained on. D&D is a cultural product and therefore still has the marks of the sexist and racist culture that created it.

Imposing strength limitations on female characters while allowing elves and working magic is silly. And enforcing material restrictions on female players in a wholly intellectual pursuit meant to be “fun” is beyond me. I’ve been playing since 1978 and now publish RPGs, and here are my observations for what they’re worth:

(1) Gamers are (and were) drawn from the larger culture. And back in the 70s, there were widespread (and largely unexamined) assumptions about gender. This would inevitably impact the game as published, just as it impacted the people designing and playing said games at the time…

(2) Conversely, D&D (and its imitators) were creative and imaginative people who took the whole “rules as a guide” thing to heart. They (and that means we) happily added, changed, and/or ignored rules wholesale. The minute we bought a ruleset, it became OURS. We weren’t beholden to the designers or to anyone else but ourselves and the needs of our group. I mean, who was the game for? Them? Or us?

And so we had a collision of traditional social mores and more progressive ideas warring both in the community and (often) within the individual. This is the human condition. But I’m glad we’re moving on. And I hope we continue to do so…