This piece attempts to document the context and tangible elements created by two live-action role-playing games (larps) that I co-authored: Cady Stanton’s Candyland and Candyland II: Ashley’s Bachelorette Party, run at Intercon in 2013 and 2014, respectively. These larps aimed to explore women’s experiences with sexuality and encourage a dialogue about sexual desires, experiences, and conflicts. Though there are several other live-action scenarios dealing with sex – notably Summer Lovin’1, which deals with a series of one-night encounters at a music festival, and Just a Little Lovin’2, which focuses on the early days of the AIDS epidemic – co-author Julia Ellingboe and I wanted to create scenarios that focused specifically on women’s experiences and how sexual experiences intersect with issues like religion, feminism, family, sexual identity, and age. Our goal was to create games that would allow players to explore these issues in a way that would be both informative and entertaining, and we felt that larp would be a particularly useful medium through which to achieve this goal.

Markus Montola and Jaakko Stenros3 argue that unlike mediated forms of imagining, like movies or books, larp scenarios provide both mental and bodily engagement. Larps provide a safe space for players to try new things and to be more adventurous, receptive, and open-minded. Players can explore different perspectives and experiences through inhabiting their characters. The “magic circle of play serves as a social alibi for non-ordinary things”4, allowing players to act in ways that they ordinarily would not, by taking on fictional character roles. Because they are not acting as themselves, players may feel free to take on attitudes or behaviors considered taboo using the excuse that it is the character committing these transgressions5.It was exactly these aspects of larp that drew us to the idea of using the medium to explore diverse women’s experiences with sexuality. With that in mind, we designed the activities within the Candyland games to help players explore their characters’ sexual experiences and preferences, leaving open a space for the player to either play “close to home” or to explore a very different set of experiences than their own.

We envisioned a game that would examine women talking about sex in an open and positive environment. These kinds of discussions about sexuality in the U.S. are still rare. There are few spaces where such discussions can take place, particularly among people who are not friends or intimates. Getting a group of strangers to talk about sex opens up possibilities for sharing a wider variety of experiences, and perhaps rethinking assumptions, but it also means confronting feelings of embarrassment and shyness. We thought the larp medium could provide some specific tools for overcoming these barriers. To this end, we designed our games to center around the Candyland “fun parties”, Tupperware-style parties for sex toys. Cady Stanton’s Candyland takes place at a feminist bookstore in the 1970s and Candyland II: Ashley’s Bachelorette Party takes place at a present-day bachelorette party at a community center. Both larps feature games within a game, as the “hosts” of the parties lead the characters (and therefore also the players) through a series of activities and games meant to explore sexuality and desire in a fairly light-hearted and humorous way.

My goal in documenting these games here is to provide a resource for particular techniques used to facilitate open, productive discussions about sexuality. Larps are a medium that can address a myriad of topics and can do so in many distinct ways. Documenting larps allows future authors and organizersto draw on past techniques in their own games, or to approach similar topics using different means.

While developing the game, we attended a workshop run by Not Your Mother’s Meatloaf6, a sex education zine and book that portrays sexual narratives in comic format. We were inspired by the argument that the comic format allows for an exploration of embarrassing and taboo topics through humor. We began thinking about how a larp scenario could also provide a different space to explore sexuality and address potentially controversial, embarrassing stories in a way that was fun and humorous, but might also deal with serious issues. Humor, as the creators of NYMM demonstrate, is a great way to approach difficult topics and we looked for a mix of activities that would provoke laughter while also allowing for people to talk about sexual experiences and desires.

As we began writing the Cady Stanton’s Candyland scenario, we thought about ways we could better tap into larp’s ability to engage both the body and the mind, as well as the idea of inhabiting an experience. We wanted players to do more than just talk; they should engage with their characters in a embodied way, and get a chance to act out and play with sexuality as their character. We consulted websites for real sex toy parties, such as Ann Summers and Pure Romance Parties, to find activities and tips. We also drew on older, sex-positive, consciousness-raising activities from the second wave of the feminist movement, such as providing players with pages from the Cunt Coloring Book and discussing masturbation tips. A deck of “adult” party games also provided some ideas. We then curated and designed our activities to suit various purposes. We took several games directly from their sources (complete with titles) while other games were created based on combinations of games, or adaptations of existing activities. Some activities were meant mostly as ice-breakers, allowing the players to laugh at themselves and helping them move outside their comfort zone. In “Pussy Galore”, for example, one character was blind-folded and had to guess which character’s lap they were sitting on by asking them to “meow” or “roar”. Once the players were warmed up, we introduced activities meant to explore characters as well as open up discussions about differences and similarities in desire. An activity called “Forbidden Fruit” asked characters to anonymously write three things they can never get enough of, which were then pulled from a hat and other characters tried to guess who had written each one.

One of our primary goals was to to help players engage in a more tangible way with sexuality in order to encourage a different mode of engagement for the players’ benefit as well as to produce tangible representations of the ephemeral elements of the characters and their relationships to each other. We utilized two activities in particular to achieve this goal: vulva sculpture/erotic sculptures and lingerie drawings, both of which I will be documenting in this essay.

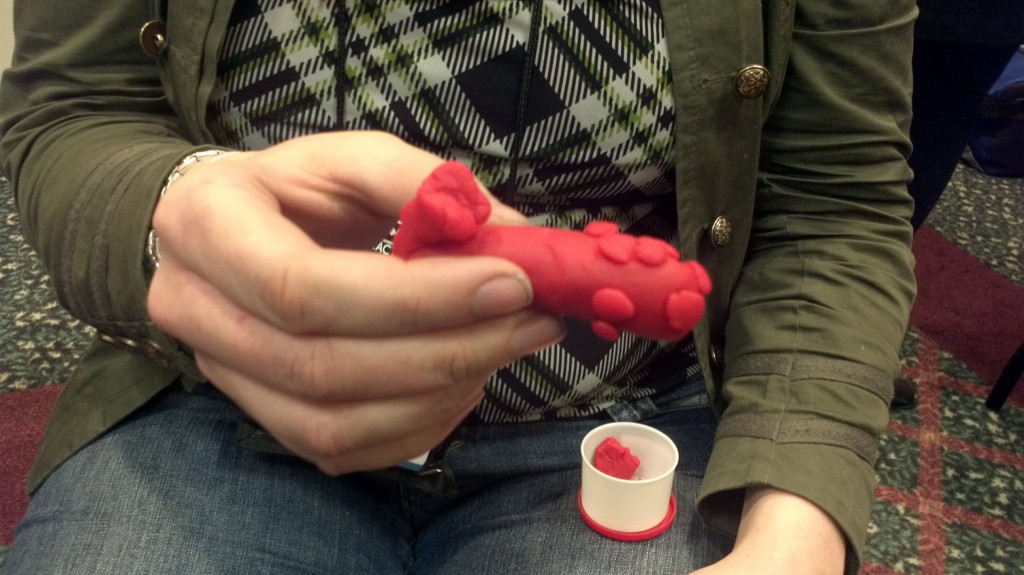

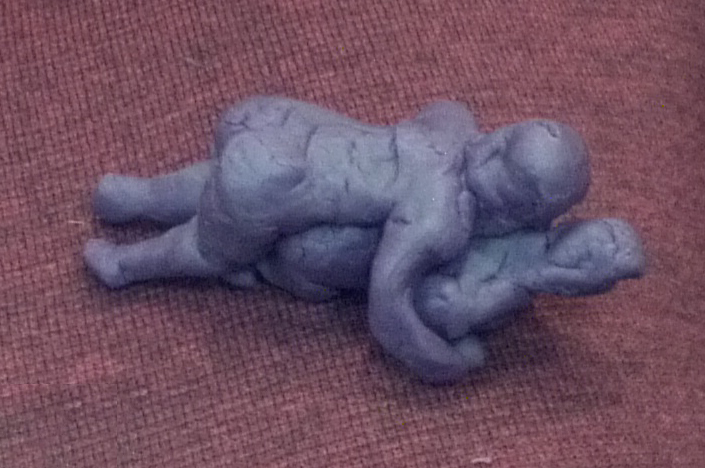

In Cady Stanton’s Candyland, the party hosts gave the characters Play-Doh and asked them to construct vulva sculptures and then share their creations with the group. Characters in the game expressed a variety of opinions about the activity from embarrassment, to frustration, to excitement. The variety of artistic representations of the vulva was quite wide. Several characters were nervous about their ability to construct an “accurate” vulva. Some characters consulted the vulva coloring pages left out in the game space to help them with their sculptures. While players seemed to enjoy the activity in-game, there did seem to be some reluctance to keep the sculptures around after the game and worries about what the next group in the space would think if they found the sculptures. Several players destroyed the sculptures at the end of the game in order to put away the Play-Doh, so only a few sculptures were photographed. Yet the photographs serve as a reminder of the activity in a way that the simple description of the activity can’t quite capture.

During Candyland II: Ashley’s Bachelorette Party, we attempted to do a better job of documenting the tangible ephemera created during the game. During this game, characters were also given tubs of Play-Doh and asked to create “erotic” sculptures. Because the parameters of the activity were wider than in the first game, the variety in these sculptures was also much wider than with the vulva sculptures and therefore communicated a lot more about the characters. For example, the character of Ashley’s grandma was rediscovering her sexuality after being widowed, and she created an especially detailed erotic sculpture of a man and a woman engaging in intercourse. The sculpture evoked shock and hilarity in the other characters, depending on their relationships to the grandmother and their own comfort levels with sex.

In the second activity, characters were asked to draw pictures of the lingerie they were giving to bride-to-be Ashley as gifts. These drawings documented both the individual characters’ own tastes as well as their relationships to Ashley. Some characters were Ashley’s friends, some were her family (including her mother, sister, and grandmother), and other characters were future in-laws. Ashley was asked to guess which character had made which drawing, an activity that also helped explore Ashley’s relationships with these other women. Ashley had an easy time guessing which character had created which drawing, since her character had the most knowledge of all the other characters. This activity was another that exposed surprising revelations and challenged preconceptions about the characters that we’d built into the game. For instance, Ashley’s libertine friends were often shocked when Ashley’s future sister-in-laws, both conservative Christians, demonstrated their wide-ranging sexual experiences and preferences. While the drawings we collected at the end of the game don’t fully communicate the relationships and experiences they demonstrated during the game by themselves, they do leave behind a record of how drawings, as opposed to words, can be used to access different information about characters and character relationships.

As other authors have discussed7, larps are evanescent events, which makes documenting larps often difficult to accomplish. This raises questions about how accurately the experience of live-action play can actually be captured. Can the experiences from a larp scenario accurately be communicated to people who did not participate? While the two Candyland games created tangible artifacts linked to characters’ ephemeral experiences with sexuality and their interrelationships, much of this information is lost outside the context of the game. Looking through the photographs of the erotic sculptures, it is hard to remember the stories behind some of them. While the grandmother’s sculpture stands out in my memory, others have faded, so I’m left unsure as to which characters created them and what their explanations of the sculptures were during the game. But while the desire to recapture the game for those who did not attend may have been the initial impulse for documentation, I now believe that there is a different value in these artifacts.

Although documentation may not be able to recapture or recreate a past larp event, there is still value in creating tangible reminders of a game for those interested in larp design. While the particulars of these larps may be lost to those who did not play the game, documenting them serves to add new tools for future larp designers to explore. I believe that these activities helped players more fully engage with their characters while also allowing them to explore sexuality in a new way. Although it might not be possible to capture the specific relationships and interactions from the game, documentation of the game might encourage other designers to incorporate some more creative activities in their games, such as crafting, that that engage the tactile and visual senses. Designers might also be inspired to draw on ‘real-world’ resources, such as party games and historical documents as we did, to implement activities that help connect players to their characters and to each other. While our Candyland games focused on activities meant to explore women’s sexual experiences, designers should consider how activities that access bodily engagement and the idea of inhabiting can be used to explore a wide variety of topics and social issues. As my documentation here evinces, larp techniques tend to be most successful when they take advantage of character alibi in order to allow players to explore ideas or behaviors that they would not normally feel comfortable with.

–

Featured image by Mel Green @ Flickr CC BY-NC-ND.

–

Katherine Castiello Jones is a Ph.D. candidate in the Sociology department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she has also completed a graduate certificate in Advanced Feminist Studies. Her interest in role-playing started in college with a game of Call of Cthulhu. Moving from player to game master and designer, Jones has been active in organizing Games on Demand as well as JiffyCon. She has also written and co-authored several live-action scenarios including All Hail the Pirate Queen!, Revived: A Support Group for the Partially Deceased, Cady Stanton’s Candyland with Julia Ellingboe, and Uwe Boll’s X-Mas Special with Evan Torner. Jones is also interested in how sociology can aid the study of analog games. She’s written for RPG = Role Playing Girl and her piece “Gary Alan Fine Revisited: RPG Research in the 21st Century” was published in Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Role-Playing Games and the Media.

Interesting read. Thanks for documenting so the rest of us can get a glimpse and be inspired. ;)

Quite interesting indeed! I love the photo documentation and written descriptions.

Some questions, and I apologize if you covered these items: Were the players all female? Were the roles all female? Was crossplay allowed?

I’m wondering how we could create a similar sort of role-play environment for a mixed gender group, remembering fondly Summer Lovin’ in this regard.

Great questions! The characters in both games were all females but the players were mixed gender. Crossplay was encouraged. I think we had two male players in each game.

Awesome! How did gender affect the play, do you think, if at all?