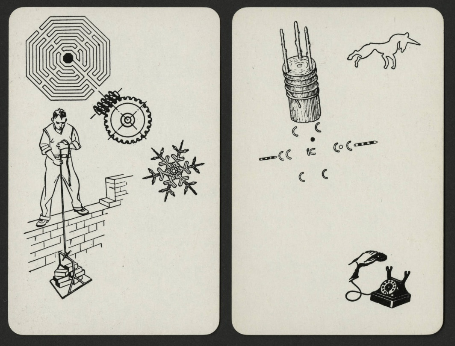

George Brecht’s Deck: A Fluxgame (1964) is a singular object, one that hovers between toy, game, and puzzle. It consists of playing cards printed with black-and-white images, collaged from encyclopedia drawings, diagrams, and photos.

The subject matter is wide-ranging and comes from specialist domains: mechanics, optics, architecture, fluid dynamics, sport, etc. The sixty-four cards have neither suit nor number and, despite the suggestion of divisibility into eight groups of eight or four groups of sixteen, clear categories are wanting. The meaning of each individual card is a mystery. The collages often seem to generate thematic associations or visual puns, but they simultaneously resist such interpretations. Instead of looking for an interpreter, the cards need to be handled, to be spread out on a table and piled up, to be shuffled and dealt. The game includes no instructions, rules, or goals, and only the work’s title and materials suggests it is a game at all. Yet, the cards ask to be played with, even without any explanation of what that means. People invent all sorts of games with Deck, they collaborate to improvise stories and tell fortunes, they use the cards as prompts for performance, to inspire drawings, and much else. In Deck, one confronts the riddle-like character that pervades all of Brecht’s work.

Deck, and George Brecht’s art more generally links together chance, indeterminacy, and freedom through play. There has been recent work in game studies on uncertainty as a category that keeps games tense and lively, and this article expands upon that work in a case study to show three things.1 It argues that uncertainty can be used intentionally and determine the design of games. It also makes a case for being a little fustier with the concepts—like chance, indeterminacy, ambiguity, and the like—that we use to describe uncertainty. Finally, games do not simply mimic the world’s uncertainty, but give metaphors for conceptualizing the world as uncertain in the first place. The idea of chance, as Brecht recognizes, is always a worldly idea that depends on the equipment capable of exemplifying it.

Games provide such equipment in the form of dice, cards, coins, roulette wheels, lottery draws, and spinners.2 Brecht’s studies of probability theory and the philosophy of science were what first drew him into the orbit of contemporary art.3 Trained as a chemist, Brecht spent the first fifteen years of his career with Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson, during which time he began experimenting with chance procedures in drawing and painting. A night class introduced Brecht to the methods of Dadaism and Surrealism, as well as the action painting of Jackson Pollock and the composition methods of John Cage. He began to correspond with Cage in 1956, and wrote an essay on chance methods in science and art the next year. When Cage offered a course in experimental composition at the New School for Social Research in 1959, Brecht jumped at the opportunity. Each week of this class, Cage would give a minimal and odd prompt for composition, and during the following week the class would perform and discuss the works that resulted. In that space, Brecht met and collaborated with future members of Fluxus, an artistic movement of the 1960s that tried to merge art in everyday life. For many Fluxus artists, games, jokes, and toys were an ideal way to accomplish this goal—especially when they were made in a skewed or disrupted manner.4 During these sessions, Brecht began to use chance as a part of the performance process itself. By incorporating text-based instructions as elements of a musical score, Brecht could program moments of indeterminacy for the viewer or performer. Initially, Brecht composed complex tables of values that linked a feature of a playing card to a feature of a performance. For example, his first complete score, “Motor Vehicle Sundown (Event),” is a piece to be played by any number of individuals, each of whom receives twenty-two shuffled cards with simple instructions for operating a vehicle. The cards include instructions such as: “Head lights (high beam, low beam) on (1-5), off,” or “Accelerate motor (1-3).”5 Numbers following the instructions give the performer an optional range of durations for the performance. The result is a structured-but-aleatory cacophony, where cars come into and out of harmony with one another. Similarly, in “Card – Piece for Voice” the suit of an upturned card instructs the performer to produce a sound, according to the schema “Hearts: Lips / Diamonds: Vocal cords and throat / Clubs: Cheeks / Spades: Tongue,” while the card number represents the duration of that sound. Other early works operate in the same way, such that each performance changes based on the shuffle.6 In 1959, playing cards were Brecht’s favored method of introducing chance into his events, of breaking performers out of their habits, and of taking away the artist’s personal control.

Two common reactions often greet chance-based work, and Brecht’s canny and preemptive defense against these reactions reveals his view of the artist’s function.7 A first criticism is often lobbed at the very possibility of chance in art. The universe, by these lights, is determined as an endless and implacable causal chain, and any seemingly random work—such as a piece of automatic writing—can easily be traced back to a proximate cause in the artist’s life. Brecht responds scientifically to such skepticism about chance. Since the rise of probabilistic thinking in the 19th century, the notion of strict causality has been untenable, and the theorems of Kurt Gödel and Werner Heisenberg show that uncertainty is the bedrock of reality. Rather than trying to trace uncertainty to ultimate causes—which will always be uncertain—Brecht brings into focus the proximate and experiential quality of uncertainty. Chance only becomes visible for Brecht when it matters to the observer, when it becomes felt.

The second criticism concerns the ethics of using chance-based procedures. This criticism contends that far from reducing the artist’s agency and control—as in Cage’s ideal of egoless art—aleatory methods actually extend control at a more abstract level. Setting up a system using chance determines the parameters within which chance can fall; the artist knows that a die will only ever give an answer from one to six. Chance operations, in this view, conceal a will to an even greater sense of control, one that wishes to abolish chance itself. Again, Brecht’s response is that of the scientist. Throughout his career, Brecht considered his art as a kind of research. Rather than an ethical constraint, Brecht uses chance as an epistemological tool for creating bias-free experiments. Control is important to any experiment, but introducing chance creates a testable variable whose possible outcomes can surprise the observer. Giving up control is always a relative procedure for Brecht, the production of a zone of unknowing that is partial.8

Brecht’s vision of aleatory aesthetics, especially as it is articulated in “Chance-Imagery,” is more systematic than many of his contemporaries. Yet, Brecht’s work undergoes a sudden change around 1961 because of a contradiction introduced by chance.9 After that date, the elaborately structured possibilities of his playing card works are paired down dramatically. He starts to write simple directions that sometimes amount to a single word and rarely stretch to more than a handful. Indeed, while actual cards remain important for his event scores, as in Water Yam (1963), their content no longer seem to instruct at all, but merely call attention to ongoing processes within the world. Pieces, such as “Drip Music,” which in 1959 read “A source of dripping water and an empty vessel are arranged so that the water falls into the vessel,” are simplified to “Second version: Dripping.” These works drop the programmatic and explicit tools for generating bias free randomness, and raise a question about the role of chance in Brecht’s method.

Authorial control came to present a problem for Brecht after all. In a 1966 afterward to the belated publication of “Chance-Imagery,” Brecht writes that he could not “have foreseen the resolution of the distinction between choice and chance which was to occur in my own work.”10 Brecht was not worried about exerting a structuring control over the outcome of situations, but he did recognize that his scores imposed an alien will upon people.11 Cage said of one early piece that “[n]obody ever tried to control me so much,” and Brecht later reflected that he “learned that lesson there, I realized I was being dictatorial.”12 How not to dictate became a problem in his work, and if it was influenced Cage’s ethics, it was equally the concern of a scientist accidentally biasing his results. By moving from elaborate card pieces to brief and simple scores, Brecht solves this dilemma by leaving the realization of a given work up to the participant. In his notebooks Brecht invents the “enigmatic notion of ‘choiceless choosing’” as a synthesis of each constraint.13 It is a phrase that points to his belief that choice is ultimately illusory, and can be integrated as one more variable in an experiment.14 In the later part of his career, Brecht would even claim that “I’m not at all sure that I’ve ever invited anybody to think or do anything….I don’t demand anything.”15

Chance continues to play a role in Brecht’s proto-minimalist events through the coincidence of word and world. He understands all sorts of everyday occurrences to fulfill the conditions for an event like “Dripping,” without any need for a performer. Noticing a leaky faucet, a rainstorm, or sweat on a hot day all count as valid realizations of the score. For the observer, each is a random occurrence that just happens to coincide with the printed word, which makes the chance character explicit.16 Chance events, though, are only one uncertainty that these scores can provoke. Other kinds of uncertainty are just as, or more, important to Brecht’s style. Brewing a pot of coffee as part of a morning routine, for instance, produces a “dripping” that is neither dictated nor random but habitual. The result is ambiguous rather than indeterminate, a small kind of distinction, but one to which Brecht’s notebooks pay attention.17 During this period Brecht began to thoroughly explore the ambiguity that a performer faces when interpreting such scores.

With the reduction of chance operations, we might expect to see a similar decline in the toys and games that Brecht used to model chance. In fact, exactly the opposite occurs. Toys become a staple element of the assemblages and Fluxkits that Brecht created after 1962. Hand puppets, tops, skipping rope, all kinds of balls, alphabet blocks, dominoes, chess pieces, and many more such objects appear throughout his work. Dice and cards persist, but without the one-to-one correspondence between card and instruction that characterized his early scores. Brecht also produced a series Fluxkits with George Maciunas that take games as an explicit theme. In the Games and Puzzles (1965) series, Brecht gives the player outlandish tasks that exacerbate the ambiguity of his simplified event scores. “Swim Puzzle” for instance, consists of a sea shell or ball, and the instruction “Arrange the beads such that / the word CUAL never appears.” “Ball Puzzle” gives the prompt: “Find ball under bare foot / Without moving, transfer ball to hand.” These tasks feel impossible, but do not demand any heroic effort, only a change in perspective that is just out of reach. Sometimes the task is too easy—CUAL will never appear—and the lack of satisfaction seems to call for another answer. Sometimes the impossibility comes from a self-imposed constraint—I cannot ask someone to move the ball for me. Brecht himself experiences his own puzzles in this way: they are difficult, he writes, “for me too. For one of them it took me several years to figure it out…. I have enough experience to know that when an idea like that comes to me it has to have a solution.”18 Brecht’s puzzles give rise to their own answers.

Toys, games and puzzles thus continue to serve as models of uncertainty for Brecht, but in a sense that goes beyond chance. Unlike games of chance, puzzles are ordinarily determined: they have a right answer, and that answer becomes trivial and obvious after it has been solved. Before one grasps the solution, and while knowing it is fully determinate, the puzzle remains entirely uncertain for the solver. By provoking minor paradoxes, Brecht’s puzzles extend this feeling indefinitely. Despite this difference, both puzzles and games of chance provoke the same feeling of playfulness. In both, the world feels stacked against the player—either through enormous odds, or through incomprehensibility. In both, it is the smallest possible gesture that upends the world. A single cast of a die or turn of a card is enough to change one’s fortune, and a slight shift in perspective makes a nonsensical riddle seem obvious. In both, there is a deep historical connection to the rhetoric of fate and destiny.19 Julia Robinson characterizes this aesthetic of Brecht’s works through “[t]he irony, the quirky reversals, the wit and the occasional moments of sublime minimalism” that it elicits.20 The point I want to make is that his style is rooted in a familiar pleasure of games, one that comes from exacerbating uncertainty, and one that marks out Brecht’s work as playful.

This context helps illuminate the game of Deck that initially seems so hard to parse. Like Brecht’s early work with playing cards, Deck uses cards to highlight the effects of chance. After internalizing the problem of choiceless choice, Brecht does not instruct the player about how to play with Deck. The player must invite the game into her life. The individual cards still function, as in “Motor Vehicle Sundown (Event),” as possible prompts. What the cards prompt, however, is ambiguous and riddle-like; they have more in common with the interpretive conundrums of Brecht’s impossible Games and Puzzles. The two modes of chance and puzzling come into a tighter relationship in Deck than anywhere else in Brecht’s work, and chance is ultimately subordinated to interpretation. It is impossible to take in the whole of Deck at once, to try to make global claims about its meaning. So, a randomly dealt hand of cards becomes the ideal way of grasping, quite literally, a subset of Deck and making sense out of it. Chance thus becomes one moment within the larger movement of Brecht’s aesthetic of uncertainty.

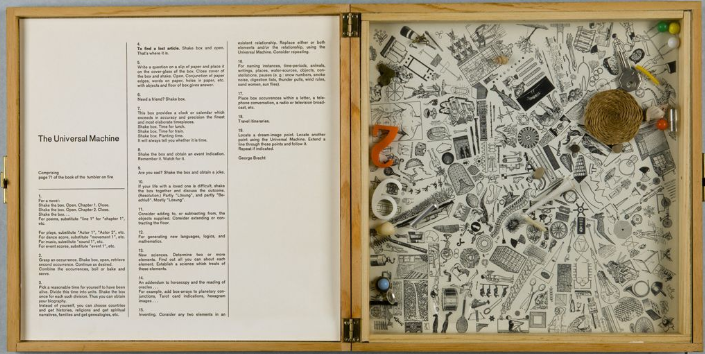

We can trace the relation between chance and interpretation further by comparing Deck with its twin, Universal Machine II (1965). This was a work composed in the same year, and with the same set of encyclopedia imagery, which Brecht cut up again and re-arranged to make Deck.21 In Universal Machine II, the diagrams are condensed onto a single piece of paper, which has been glued onto the back of a wooden box. The box is covered by a sheet of glass, and contains some assorted objects—buttons, metal clips, an awl, or stones—which are unique in each piece. On a facing cover are suggestions for using Universal Machine II, such as “For a novel: / Shake the box. Open. Chapter 1. Close. / Shake the box. Open. Chapter 2. Close” or, “New sciences. Determine two or more elements. Find out all you can about each element. Establish a science which treats of these elements” or, “Need a friend? Shake box.” Like Deck, the act of shaking subordinates chance operations to a moment of interpretive uncertainty. Each time, a gestalt forms between the background images and a piece of debris, which draws a connection between two or more images in contingent and reciprocal ways. Unlike Deck, though, Universal Machine II explicitly writes out its possible functions, and thereby draws attention to the meaning-making operation.

Universal Machine II connects the most disparate things into a single universe of sense. By establishing chance relations between its objects, it produces an ontological flattening. An acrobat exists in the same sense as an architectural drawing and a snowflake. Deck extends this operation, which the debris highlights, through a chance combination of cards. Rather than separating objects into things and relations (illustrations and debris), Deck makes the illustrations do double duty by allowing the picture plane itself to move, as cards are re-arranged by the player. The title of Universal Machine II calls attention to a universal flattening. At the same time, the title encodes a critical pun, one that sets up a contrast between Brecht’s work and the computational flattening of the universal Turing machine.

The Turing machine, described by Alan Turing in 1936, is a theoretical model of a computer that describes how it is possible to build a machine that can perform any computation by reading instructions from a tape, and transforming those instructions according to a table of values. Brecht was interested in computing, and collaborated with James Tenney, a pioneer of computational art in the 1950s.22 The above description of Turing’s machine—whose first iterations were operated with punch cards—is clearly analogous to Brecht’s early use of playing cards to transform an input into a variable output. Indeed, one of Brecht’s commentators, Henry Martin, describes his work as “an enormous computer insofar as it accepts any and all information that one cycles into it.”23 However, with his transition away from instructions, Brecht’s work no longer establishes a universality through the computer’s ability to reduce the world into a series of calculable bits. In contrast to computation, Universal Machine II borrows a model of universal connection from the encyclopedia form, which establishes an aleatory and indeterminate connection between entries. Encyclopedia diagrams use visual strategies to depict objects from a null or neutral subject position, whose surrounding “whiteness is an arena of potentiality that fosters connections without fixing them or foreclosing thought experiments.”24 The Universal Machine II thus reveals a commitment to a particular kind of universality shared by Deck, which suggests anything could be connected to anything else without the mediation of calculation or instruction. Deck further refines some elements of Universal Machine II that remain tied to Brecht’s earlier methodology. Deck stretches out the neutral white space between the densely collaged encyclopedia diagrams, and eschews the ontological difference introduced between debris and representation. It also manages to suggest a world of possible uses in the material and habitual affordances of cards, without a page of explicit directions.

Deck is singular not just because it comes with no instructions, goals, or rules for play—which is equally true of toys and puzzles—but because Brecht uses all the tools at his disposal to embed a sense of a goal and a way of developing rules in the equipment of play itself. Playing with Deck is crucial to discovering these affordances. In my experience with Deck, there is a basic game that emerges and one that Brecht also seems to have played. In one interview, he describes using Deck in such a way that each player makes up rules “as they go along and then unmake[s] them…each player can criticize the other’s rules, intervene, and change the rules.” Brecht gives an example of one such rule, where “[e]veryone had to take three pictures from three cards and turn them into a joke, improvising.”25 The invitation of the encyclopedic images and the chance structure of the cards allow Deck to make the transit from toy to puzzle to game, and back again. It gives the player a push and a hint, but does not give them a means or a map. It is rule-governed but without any rules, purposive without any purpose. Deck marks the most accomplished synthesis of Brecht’s thinking about chance, instructions, and uncertainty.

–––

Featured image from George Brecht’s “Ball Puzzle” (1964), label by G. Macunias.

–––

Peter McDonald is a PhD candidate in English Language & Literature at the University of Chicago. He received his MA from Simon Fraser University and his BA from the University of British Columbia. His current work is on the hermeneutics and aesthetic playfulness of 20th-Century anthropology and literary theory as applied to video games and new media.

Want to be updated. Thanks