Peace games don’t sell.

–James F. Dunnigan

War has always played quite an important role in board games. For a long time, this fact posed few political or ethical problems. In pre-modern Asia and Europe, stylized battle simulations such as Go and Chess were highly respected cultural artifacts. In 19th-Century Prussia, the game Kriegsspiel, enthusiastically endorsed by King Friedrich William III, was used as a conceptual tool to train the officer corps. In the 20th Century, after the bloodshed of two World Wars –– wars waged by German generals still employing Kriegsspiel to test their plans –– the mixing of game and war gradually became seen as a problem. Already on the eve of the Great War, science-fiction writer H.G. Wells, both a socialist and wargamer, was aware of the politically slippery nature of his hobby. In his Little Wars (1913), one of the very first rulebooks for miniature wargame ever published, Wells somehow tries to “calm his conscience”, saying that his game can help people to grasp the horrors of war. His message is essentially: “Do not make war, play it”. In less than a year, Europe would fall in one of the most horrific conflicts of human history, whose ending would lay the foundation for a new, even more terrible world conflagration.

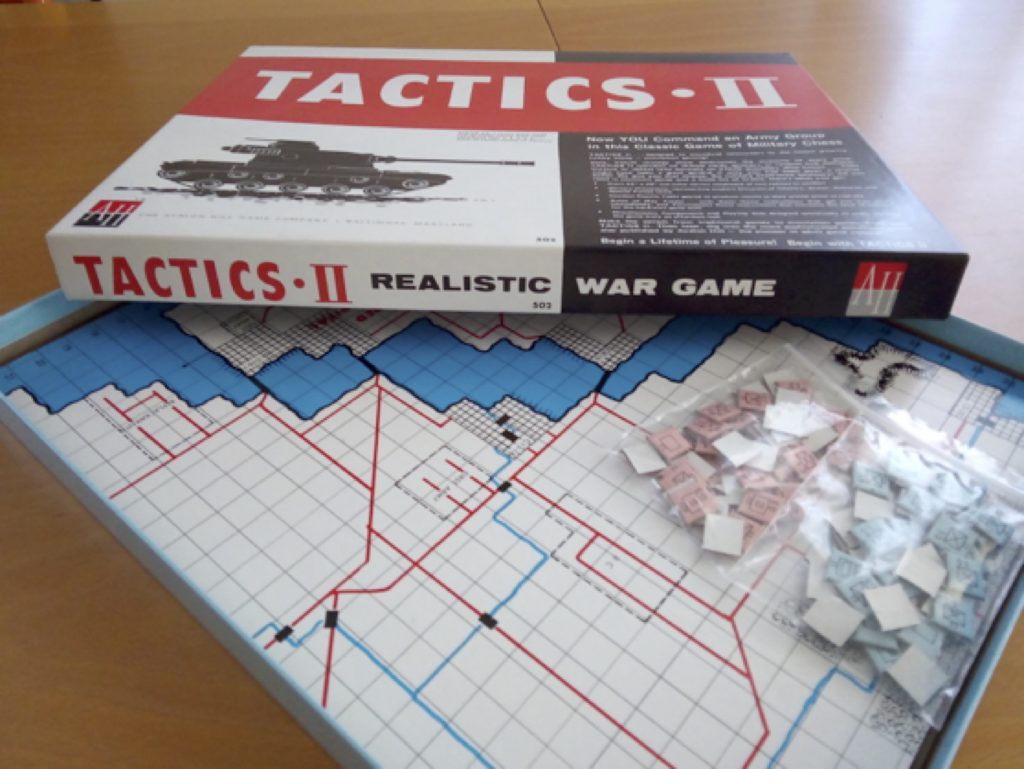

As legendary wargame designer James F. Dunnigan noted, it is no accident that the modern wargame hobby was born in the United States, which had triumphed in both world wars without any direct experience of enemy occupation or aerial bombings of its territory (beside Pearl Harbor). After 1945, Europe was not a very receptive place for games dealing with war. European game designers produced some successful war-related games, such as Albert Lamorisse’s La Conquête du monde (1957), known in the English speaking-world as Risk, but this game conveys quite an abstract representation of warfare, while the great novelty offered by American wargames was precisely their so-called “realism”. The very first hobbyist board wargames designed by Charles S. Roberts in the late 1950s, greatly stressed this aspect, as you can tell from the box covers of games such as Tactics II (1958) and Gettysburg (1958).

In his informative, superbly illustrated War Games and Their History, C.G. Lewin contends the usual notion that wargaming, as a hobby and a commercial activity, was invented by Roberts and his Avalon Hill Company in the 1950s.[2] Lewin sketches a centuries-long genealogy preceding Avalon Hill games. The point, of course, is what we mean by “wargame” and why its lineage being in the 1950s, not earlier. By no chance, the title of Lewin’s book spells it as two words, implicitly distancing itself from the industry’s lexicon, where it is spelled as a single word. Lewin labels as “war game” every board game that deals with war. But the vast majority of the games he discusses use warfare just as a background for game mechanics with no simulative aspirations. Even the very few pre-1950s games that present some of the key features of early Avalon Hill’s productions, such as a map with a square-grid and counters representing military units, are very crude as simulations. In the game that Lewin mentions as the first commercial board wargame, Arthur Renals’ War Tactics, or Can Great Britain Be Invaded? (1915), which preceded Roberts’ achievements of more than four decades, combat takes the most naive and abstract form: “pieces capture by leaping over the opponent as in Draughts”.

In this article, I stick with the traditional notion that hobby wargames were invented by Charles S. Roberts in the 1950s. I focus on two key elements of these games. One is realism. Like Kriegsspiel, wargames simulate the main features of warfare: terrain effects on movement and combat, logistics, weather, operational capabilities of the different military formations etc. As one can easily imagine, recreational wargaming was tightly connected to popular history from the very beginning. Wargamers often were – and still are – military history buffs. Strategy & Tactics, the main wargame periodical since the 1970s, calls itself: “The Longest Running Military History Magazine”. Thus in order to really enjoy a wargame, players are intended to perceive it as historically accurate. I will return to this connection between wargame and military history at the end of the article. The second question I focus on is the wargame community. Games such as War Tactics, or Can Great Britain Be Invaded?, and the other titles mentioned by Lewin, were not just elementary war simulations. With few exceptions, like L’Attaque (1908) – the forerunner of Jacques Johan Mogendorff’s Stratego (1946) – and Risk (again, both non-simulative games), these games were largely ephemeral, as Lewin himself admits. On the contrary, Avalon Hill, soon to be followed by SPI and other companies, created a community of gamers, with its own culture and rites.

Fascinating Fascism

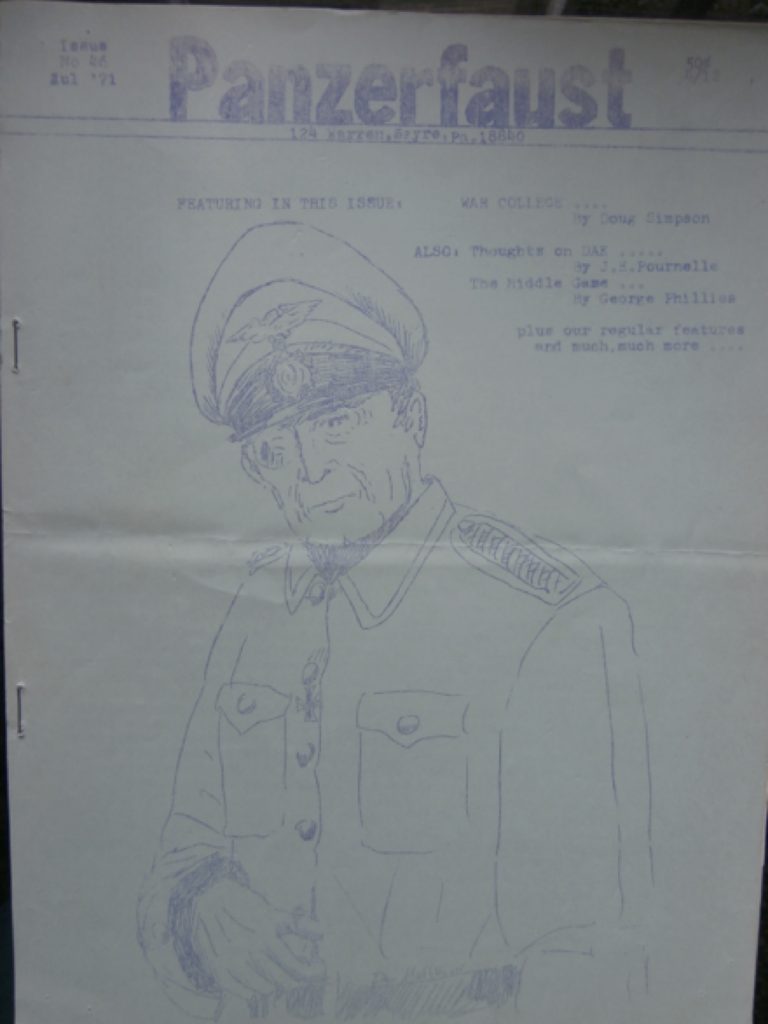

As underlined by Jon Peterson, the growth of commercial wargame as a niche hobby in the United States coincided more or less with the birth of the counterculture and the peace movement. While many young Americans were marching against LBJ’s war in Vietnam, the wargamers – a tiny group of predominantly young white middle-class males – were spending a lot of their time playing games that presented war as an interesting, if not openly fascinating, subject. Some members of the wargame community were not simply “proud American patriots”, or non-political military history buffs. Some wargame clubs and fanzines went so far as to show signs of pro-Nazi sympathies. One of the main wargame fanzines, started in 1967 by Donald Greenwood, was called Panzerfaust, after the German anti-tank weapon used in World War Two.

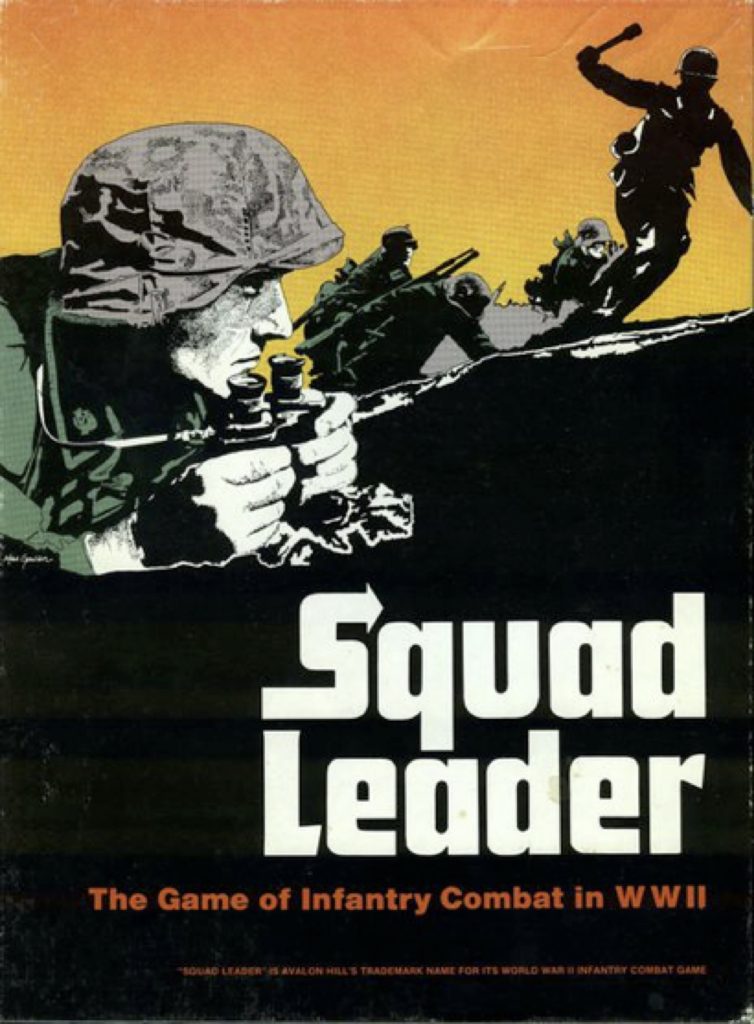

Panzerfaust’s co-editor was Gary Gygax, one of the creators of Dungeons & Dragons. Gygax had no hawkish tendencies. He was a Jehovah’s Witness and a committed pacifist. Before he turned to fantasy, his main interest as a wargame designer rested in ancient and medieval warfare. As Peterson convincingly argues: “Medieval war meant a war without industrial atrocities, a polite war, a war sufficiently removed from contemporary problems to admit the levity of games”. But many others had far less dovish attitudes. One wargame club was called The Fourth Reich, another one Panzer Lehr, after a German armor division. The question was openly discussed inside the community. In 1972, Stephen Patrick wrote an article in Moves, a “real” magazine, not a fanzine. It was titled “The Rommel Syndrome, or Wargames as a Snare and Delusion.” The author lamented the lack of respectability of wargame as a hobby, because it was “frequented by odd people who like to wear steel helmets around the house.” It was not just some crazy fringe of the wargame world. Donald Greenwood was so successful with Panzerfaust, that in 1972 he was hired by Avalon Hill, the major company in the business, to run its house press organ, The General. The titles and box covers of some games openly titillated the “worst instincts” of their audience. On the box cover of John Hill’s Squad Leader (1977), a tactical game set in World War Two, and one of the most successful wargames ever released, there is a Waffen-SS soldier, with Totenkopf insignia clearly visible on his collar.

One could object that the Totenkopf insignia is there because that’s how a Waffen-SS uniform looked like, but then we should ask why, among all the troops represented in Squad Leader, Avalon Hill chose as its cover image a soldier from the elite military units of the Nazi Party and not a US marine, not to mention the Red Army. Another game that achieved great success was James Dunnigan’s PanzerBlitz (1970). Dunnigan first published it under the quite dull title of Tactical Game 3 (1970). When it was released by Avalon Hill, the game got a much more “kinky” German name. In some cases, these newly-invented German titles could be quite mysterious. One of the most renowned examples of the so-called “monster games” is called Drang nach Osten! (1973), which means “push toward the East”. It is the name of a geo-political disposition, coined in nineteenth century Germany, and then endorsed by the Nazi Party, which postulated the necessity for the German people to conquer the lands of Eastern Europe. We could argue that, since wargamers are history buffs, they would know what this expression means. But Drang nach Osten!’s expansion is called Unentschieden (1973). Drang nach Osten! covers the first year of the war on the Eastern front, from June 1941 to March ‘42. With Unentschieden, you can play the entire conflict until 1945, provided that you have a room and six months of your life to devote to the game. Unentschieden simply means “stalemate”. Here, there is no historical or philosophical subtext; it is just a plain German word, and not a very easy one to spell. An odd choice for a commodity primarily meant for American consumers. Nevertheless, these games did sell quite well, for a niche market. According to Dunnigan, Panzerblitz sold over 320,000 copies from 1971 to 1998, and Squad Leader’s basic game 100,000. According to SPI polls, in 1977 Drang nach Osten! was number 1 out of 202 games.

Should we assume that there was a morbid fascination with Nazism among wargamers? I would say “yes”, at least in part. One of the most important sections of the aforementioned magazine The General was the “Opponents Wanted” page. In the pre-Internet era, finding somebody living in your area who shared your very peculiar hobby was not an easy task. Wargamers used ads to find playing mates. Several of these ads clearly state a preference for playing the Germans – or even the Japanese – in games on World War Two. Some ads go even further, like one from a 1971 issue, which reads: “The Fuehrer desires a good Joe to crush in Stalingrad.” Actually, some of the interest in playing the Nazis has strictly technical reasons. Besides games specifically devoted to the last phase of the conflict, in World War Two games the German player is usually the one on the offensive, at least in the first part of the game, and one could argue that wargamers normally prefer to attack. In some ads, authors say that they prefer playing the Germans in games where the Axis has the initiative, but want to play the Allies in Anzio (1969), a game about the Italian campaign, where the Germans are on the defensive from the very beginning. Moreover, one of the main pleasures in playing a wargame is achieving a result that is different from the historical outcome. You thus might want to win World War Two with the Axis, as you might want to win the battle of Waterloo with the French. It would then mean that you would have been “smarter” than Napoleon. Nonetheless, dismissing this whole phenomenon with simply technical reasons would be naïve and misleading. There was a fascination with Nazism. After all, in the 1970s, Nazi paraphernalia were widespread in American and European popular culture. Susan Sontag’s well-known 1975 essay Fascinating Fascism elaborates on this point in detail. Wargames were following the current.

Nowadays, wargames are very different on these points. As shown by Adam Chapman and Jonas Linderoth in their “Exploring the Limits of Play: A Case Study of Representations of Nazism in Games”, contemporary analog and video games dealing with Nazism tend not to show the traditional Nazi symbols, especially the swastika which, in the 1970s was commonly reproduced in wargames. Just see John Edwards’ The Russian Campaign (1974), one of Avalon Hill’s most successful games, whose victory conditions envisage capturing the enemy leader, either Hitler or Stalin. The Hitler counter has a swastika, and the SS acronym on the counters representing Waffen-SS units is even written with the iconic runic types, a really fetishist detail perfectly in tune with Sontag’s article.

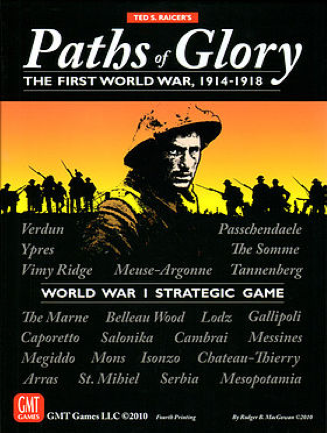

As Chapman and Linderoth note: “What can and cannot be incorporated into a game says a lot about the norms and values of the society in which the controversy arises.” Contemporary wargames try not to awaken the Dr. Strangelove lurking inside many wargamers. In The Russian Campaign, like in Drang nach Osten!, Waffen-SS counters were black, the color of Nazi uniforms, as well as the color that – according to Sontag – epitomizes the “eroticization of fascism.” In Barbarossa to Berlin, a game from 2002, the Waffen-SS counters are prudently dark grey, with no runic types. Moreover, designer Ted Raicer put Stalin in his game, represented by a counter with hammer and sickle very similar to the one in The Russian Campaign, but omitted Hitler.

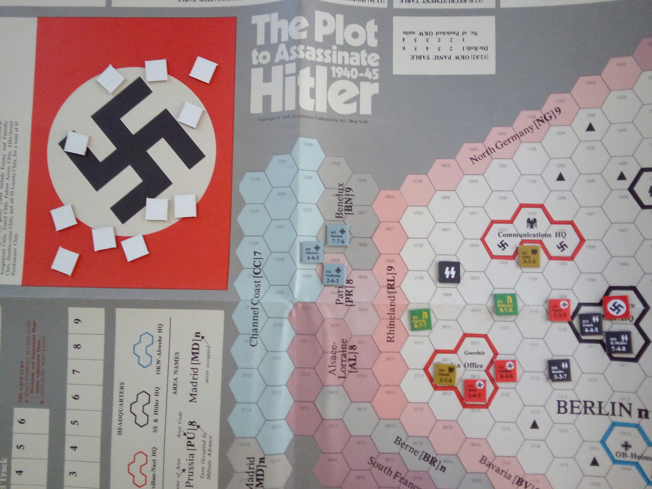

Not all contemporary wargames are so circumspect, however. The new edition of The Russian Campaign, released in 2003 by L2 Design Group, keeps the Hitler counter along with its swastika, as well as black Waffen-SS units with runic fonts. More recently, in Hitler’s Reich (2018), published by GMT, the rulebook has chapter titles in Gothic fonts. But today nobody would dare to publish something like The Plot to Assassinate Hitler, a political simulation designed by James Dunnigan in 1976, where swastikas and SS runes are literally everywhere, just as in Nazi Germany. They are not only on counters, where they designate the affiliation of the various units. There is also a big Nazi flag on the map board. It is there for simple “decorative” reasons. It is a box where players keep part of the counters. It could have been a blank space. If they designed it as a Nazi flag, if was purely for tantalizing those “who like to wear steel helmets around the house.”

Beside a few exceptions, swastikas are absent in contemporary games. In Cataclysm: A Second World War (2018), another wargame recently published by GMT, despite the fact that the three power blocs run by players are described in ideological terms, as either democratic, fascist, or communist, the flag on German counters is not the Nazi one, but the old pre-1918 Imperial flag, with three thick black, white, and red horizontal stripes.

Why this drastic change? Of course, it is a question of cultural perspective. Nazi paraphernalia, that in 1970s did not embarrass anybody in the wargaming community, and even excited somebody, are not acceptable anymore, not even in such a small community on the outskirts of mainstream culture. Today, the wargaming community is a little bit more diverse than it used to be. For example, the presence of women, both among players and designers, albeit still relatively thin, is larger than it was in the 1970s. Moreover, as Chapman and Linderoth argue, “many of these games exclude the swastika because of the legal limits relating to its use in Germany,” a major market for board games. Swastikas disappeared from military modeling for the same reason. But why should one blur swastikas in games, both analog and digital, and not in films or TV series? Again, Chapman and Linderoth are quite convincing. The point is the ludic frames, which in our society “seem to have an intrinsically trivializing property.”

Wargames, insurgency, and collateral damage

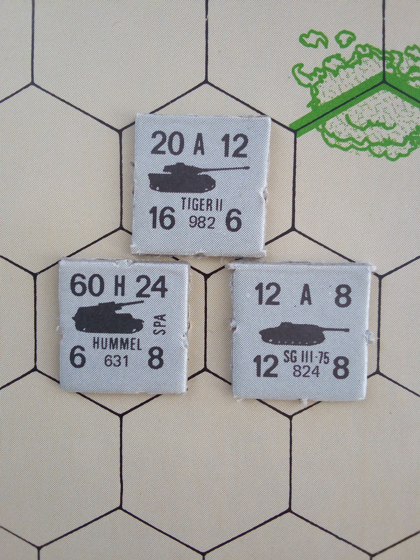

The story of commercial wargame, from its origins in the late 1950s to its heyday in the late 1970s, is a story of growing sophistication, both in graphics and gameplay. Compared to Panzerblitz, a game such as D-Day, with its simple and somewhat opaque mechanics, and with its totally unadorned counters, represents wargaming “degree zero.” It still is a fun game to play, but it clearly belongs to the hobby’s infancy, when playability counted much more than realistic simulation. Just think that in D-Day, all the Allied divisions, no matter if American, British, Canadian or French, have the same combat/movement factors, which is at least debatable from a historical point of view. Panzerblitz not only explored new paths in realistic simulation, helping to shape the genre of tactical wargame. It also introduced a new visual style, with highly refined counters, each one representing a platoon of a specific type of armored fighting vehicles, with its own name and silhouette, and its own specific combat/movement factors. To quote Sontag again: “For fantasy to have depth, it must have detail.”

But in these games, despite all the realistic details, as well as the abundant presence of Nazi lexicon and symbols, the fact that during World War Two military operations were systematically mixed with deportation and massacres of civilians goes almost unnoticed. In PanzerBlitz, among all the various German units, there are counters labeled as “Security.” They are infantry platoons with weaker combat factors than regular rifle platoons. The “Wargamer’s Guide to PanzerBlitz,” in the paragraph devoted to German security units, reads:

“These units are curious. The Germans used a hodge-podge of new recruits, veterans on leave, foreign volunteers, and local levees for security.”

Nowhere in this booklet – nor in PanzerBlitz’s rulebook – it is mentioned that the most “curious” thing about German security forces, was the Nazi notion of security itself. For “securing” the areas behind the frontlines, the Nazis meant killing Jews, Soviet political commissars, partisans, and more broadly anybody that could pose even the remotest threat to German order. In PanzerBlitz’s designer’s notes we read:

“The Germans, the ‘guardians’ of ‘western civilization’ slaughtered civilians and (captured) Russian soldiers with a ruthlessness never seen before and since.”

But these horrors have no place in the gameplay, where security platoons are engaged in conventional warfare against Russian regular units. Also in Drang nach Osten! there are German security units. The rulebook openly calls them “cutthroats,” but, just as in PanzerBlitz, they do not perform any ethnic cleansing. As game designers Brian Train and Volko Ruhnke underline in their article “Chess, Go, and Vietnam: Gaming Modern Insurgency,” contrary to what they did in reality, these units operate on the front lines, fighting the Red Army. Despite their aspiration to achieve a realistic simulation of warfare, wargames tended – and largely still tend – to offer a very tidy representation of war, more or less like Hollywood movies from the 1950s. Squad Leader presents several scenarios that depict urban combat, which is reproduced in a highly detailed way. There are even rules concerning movement in the sewer system. The only significant feature of city environment that is ignored is the presence of civilians. Squad Leader’s battles take place in a social vacuum. In Lou Zocchi’s Luftwaffe (1971), on the air bombing campaign against Germany, the Allied player must annihilate enemy cities and infrastructures, but the terrible human cost paid by the German population is never mentioned, not even in the historical and designer’s notes. Of course, the main reason why the so-called “collateral damage” is rarely mentioned in wargames is because they focus on the more “exciting” aspects of warfare: maneuvering and fighting. But one could argue that, through blurring the horrors of battle, wargame implicitly makes war acceptable.

Of course, there are exceptions. In Joseph Miranda’s The First Arab-Israeli War, 1947-49 (1997), for example, the rules include terrorism, to which both players may resort in order to empty villages of enemy population. More recently, the GMT COIN series – where Train and Ruhnke are two of the main designers – offers games focused on the so-called unconventional warfare. COIN stands for “counterinsurgency.” These games simulate various kinds of guerrilla conflicts, and here the effects of military actions on civilians are absolutely clear. In a paper presented in 2016 at the Popular Culture Association National Conference, Train describes the COIN games as “critical and subversive objects”, precisely because they “often feature morally objectionable and upsetting aspects as terrorism and violence against non-combatants.”

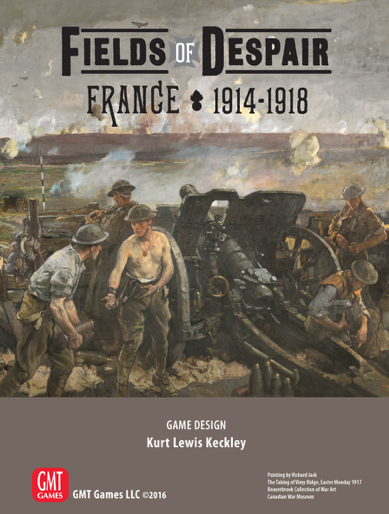

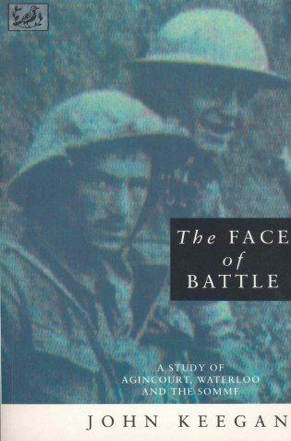

It is self evident that the origin of the COIN series lays in the geo-politics of the post-Cold War era. The world we live in is, in fact, dominated by terrorism and irregular warfare. But in the contemporary wargame scene, sometimes we find a “critical approach” even in games devoted to conventional warfare. Just take the title and box cover of Fields of Despair (2017), a game on World War One. Such a title needs no comment. As far as the picture is concerned, while the usual wargame box cover shows fighters in heroic poses, like in Squad Leader, on Fields of Despair’s box we see exhausted men performing a totally un-heroic task. They are factory workers, not warriors. And it is not just a question of packaging. Fields of Despair includes the use of chemical weapons. Usually, wargames’ rulebooks do not mention chemical warfare, because it is regarded as “morally objectionable”, just like terrorism, or atomic weapons. One hundred years after the Great War, poison gas still represents a red line governments should not cross, as shown by recent events in Syria. Including poison gas in his game, Fields of Despair’s designer Kurt Keckley did quite a bold move. How did it happen? As I already said, wargame is all about realism. But “realism” is a cultural convention that changes through time. Until the 1960s, military history was entirely focused on military issues in the strict sense: plans of attack, weapons, logistics. It was just like in wargames – war with almost no human suffering. In the 1970s, with the so-called New Military History, new topics and new methodologies arose. Scholars such as John Keegan or Eric Leed started to mix the study of warfare with cultural history, anthropology, psychology, literature. They shifted the focus from generals to frontline soldiers. The sufferings of individuals, both combatant and not, became more important. In the long run, this cultural revolution in academic history had an impact also on popular history. Just look at the gloomy representation of the Great War offered by the mass media during the war’s centenary. The leitmotiv of “the frontline soldier as victim” can be found both in a Hollywood blockbuster movie such as Steven Spielberg’s War Horse (2011) and in an art-house film such as Andy Smetanka’s And We Were Young (2015). But it all started well before the centenary. If there is an event we can take as a key moment, a symbol of the assimilation of the ideas of the New Military History by wargame culture, I would take the release of Ted Raicer’s Paths of Glory (1999). The title comes from an anti-war film by Stanley Kubrick, while the discouraged British soldier uncannily staring at us comes from the cover of the 1991 edition of John Keegan’s seminal book The Face of Battle. If, as Philip Sabin puts it, wargames are “interactive history books”, their aims and methodologies change and evolve just like those of books.

__

Featured image “Barbed wire, electric fence and ditch – Dachau Memorial site (K-Z Gedenstatte Dachau), Germany” by Glen Bowman CC-BY@Flickr

__

Giaime Alonge is full professor of Film Studies at the University of Turin, Italy. He has been Fulbright visiting professor at the University of Chicago. His main research areas are: American cinema, Italian cinema, Screenplay, Animation, Film and History, Game Studies. He started playing wargames when he was eleven.