Rob Daviau’s LEGACY system—first implemented within Risk Legacy (2011) and Pandemic Legacy (2015)—is changing eurogames and its consequences are as impactful as the mechanics that revolutionized the field in the 90s, such as “deckbuilding”, “cooperation”, “instant poolbuilding”, and “card drafting.” The huge success of Daviau’s LEGACY games has led other designers to implement it in their projects, a point that seems to anticipate that this trend will only increase with time. This article shows how the LEGACY format affects game design and play theory by introducing a series of features that reorient the gameplay experience from a focus on winning and solving and toward an experience aligned instead with narrative and reflection. This reorientation is epitomized by the LEGACY system’s embrace of permanent change and permanent death.

Since its origin, game studies has considered reversibility and nonlinearity key formal elements of games. As play elements, reversability and nonlinearity imply possibility. Despite the prevalence of these common game mechanics, the LEGACY system produces playfulness through irreversibility and lasting consequence. This sense of consequence relies on a particular type of permanent death that transforms the game environment into one which appears more similar to reality than to fiction (one where actions have permanent consequence). Hence, irreversibility affects not only the surface design of LEGACY games, but also the deep structures through which people assign meaning to play and time experiences.

The LEGACY system is similar to the “campaign” modes of tabletop RPGs. As players advance in the game they trigger certain plot points which then instruct them to open new sealed boxes of custom components. The customization cannot be reduced to that of collectible or living card games, because in a typical game session new components are discovered and the existing ones are modified permanently or even materially destroyed. Daviau explains:“We [the hardcore gamers] sleeve cards and preserve blister packs. We wipe our hands fastidiously and ban soda from the table. Some will find this game liberating. Others a horror. Many will sit on the sidelines. Of course, you can fake it and give yourself the way back. The undo. The temporary work around. It’s not hard to do that. What is hard is to put that first sticker on the board and realize that it’ll be there forever.”

In this passage, Daviau has noticed how the attention of the players has shifted from the active experience of exploration/identification to that of the irreversibility of events. If the essential property of games is a magic circle around the players, aimed at allowing repetition, then the permanence of the LEGACY format is certainly a compromise. Huizinga himself stated that “to dare, to take risks, to bear uncertainty, to endure tension – these are the essence of the play spirit. Tension adds to the importance of the game, and as it increases, enables the player to forget that he is only playing.” Daviau tries to explain the genesis of his work:

“The design started with an attempt to make a game decision matter, to up the ante, to maybe make you sweat a bit before you do something. We all make plenty of decisions every day. Many are meaningless. Some stay with us forever. […] Some decisions just make you who you are. This led us to wondering why games always have to reset. […] Games, by nature, demand that the user create the experience. We wanted to push that boundary to have lasting effects.”

LEGACY extends the experience of irreversibility far beyond the magic circle that binds the actions and the thoughts of the players inside the game. In Daviau’s games there is a combination of narrative and material irreversibility that influences the players experience. During the course of a campaign the storyline evolves through spectacular revelations such as the introduction or the death of the characters and the discovery of new data and subplots. Apart from these narrative elements, there is a series of syntactical changes: new rules are introduced and old rules are eliminated (for example by pasting stickers to the booklet paper) and a consequence is that the strategies have to be adapted in every match. Moreover, new material components are extracted from sealed boxes, and the existing tokens, cards, and board can be modified and even destroyed.

In order to understand the impact of these features we must establish a definition of games inferred by what I call a “minimal ontology”. Games are conceptual structures that players use in order to refer (mainly during communication) to certain play behaviors, which many researchers relate to particular psychological states related to interaction and fiction. The conceptual nature of games should not be confused with the material nature of toys, which I define as tools used for playing. Some games make use of toys like balls, dolls, boards, or electronic hardware, but others are completely toysless (puns, traditional games like hide-and-seek, and many forms of roleplay, for instance). In order to play, one must feel that their play is a reversible activity with no negative external effects. Games are organized to reassure the player that they will not have a negative experience when playing.

The LEGACY system maintains the magic circle by transgressing some fictional markers normally used in games, the most important of which is reversibility. LEGACY systems are designed to be board games, which stimulate forms of play slightly different from those stimulated by computer games. The latter ask players to interact with a set of affordances offered by the graphics on screen and by the interface, whereas board games require players to maintain the game’s rules themselves. Tabletop players can also cheat and modify the game without a material intervention. By compelling players to destroy game components, LEGACY produces a conflict between rules and metagame that is absent in most other games.

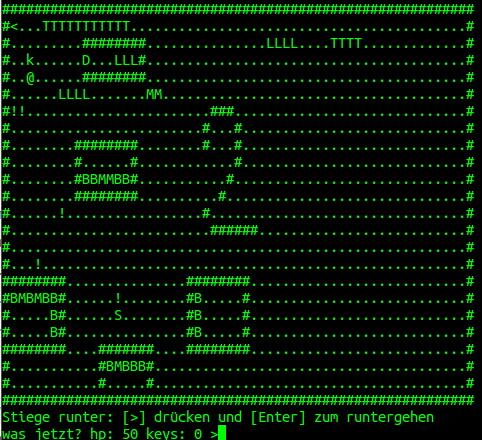

This conflict between the ludic (game rules) and extraludic (the metagame) dimensions is strictly related to irreversibility. But how to define irreversibility? Its concept is related to the events that constitute time, which is relentlessly irreversible. One model, the extensional model of time, argues that events are irreducible to objects, facts, or properties, because “they don’t exist but they happen.” As long as they happen in a real environment, events cannot be reversed; but the adoption of the magic circle—which is an entity that depends on the subjective point of view of players—constitutes gaming events as pure experience, thus introducing the potential of reversibility. A distinction between the in-game progress-time and the real world-time allows players to restart a game free to explore all the possibilities offered by the system, returning back and experiencing content more than once. Instead, the irreversibility of LEGACY changes what game scholars A. Tychen and M. Hitchens consider fundamental internal times, temporal layers and temporal frames of the play experience. The normal possibility of players to make choices, for instance by returning back to an earlier point of the game, in LEGACY is inhibited: therefore, unlike the majority of games, the time model of LEGACY games can be defined as linear.

Linear time affects our notion of game progress. According to Tychsen and Hitchens, in every game there is a sense of mechanic progress that “changes the game state in terms of the rules”, and a sense of task progress “related to the requirement of the players having to complete certain tasks (objectives, quests, etc.) to advance in a game.” LEGACY binds mechanic and task progress in a new way, so that the events which impact mechanic progress happen without the direct influence of task progress. In computer games, the consequences of the in-game actions are experienced as narrative events, passively, but in board games the freedom to not apply the requested consequences emphasizes the necessity of actions such as the elimination of a character and the modifications of the cards. Thus, in LEGACY the actions are strictly related to the staging of the events, as in theater. In a sense, the linearity of LEGACY makes the interactivity more narrative.

In order to be meaningful, event and variation have to stand out against a background of regularity: in LEGACY the focus is primarily on event and variation, and only peripherally on how to manage them. For example, Pandemic Legacy has a very deep managerial background, but its strength is the irruption of irreversibility. Variation of a game’s core rules drives many board game systems. For example, the modern folk-game Nomic has a rule-state that shifts over time through parliamentary vote, and Magic: The Gathering (M:TG) (1993) instructs players that the core rules may be superseded by rules printed on its various cards. In this sense, the variation in Nomic depends on the interaction between the players while the variation in M:TG is discreet and modular—players have the option to decide some of the rules which may shift when building their deck and choosing the cards they will play with. In LEGACY the variation is mandatory and essential, and players must implement scripted rule-changes.

LEGACY games cannot be replayed because of the extreme approach to variation they take. The uniqueness of every campaign is tied to the irreversibility of the storyline, due to the particular relation between the fictive and the gameworld time frames. The irreversibility of storyline has a digital analogy in the concept of permadeath (i.e. “permanent death”), which Lisbeth Klastrup defines as a property of games, mainly computer games, where characters can die forever, and all their characteristics are irremediably lost. Tommy Rousse argues that there is also a social component, that true permadeath occurs when a unique character’s death becomes meaningful for a player. Permadeath evokes echoes of Benjamin’s aura for interactive mass media, where users focus their artistic veneration not to the objects offered by games but rather on the experiences that such objects allow to the subjects themselves. As Debord has noticed, in a cultural environment where the artistic objects are easy reproducible, the holy importance of art does not disappear, but it is shifted towards the participation of the user. Because they are interactive, games allow users to participate in the construction of meaning: LEGACY expands this property by driving the attention of the users towards their subjective participation.

Although LEGACY implements permadeath well, there are some properties of permadeath that LEGACY overcomes or denies. Andrew Doull argues that in permadeath games the only “resource accumulated from game to game is player skill.” Klastrup has noticed that “dying is an activity similar to a number of other repeatable activities [in games].” And Ben Griffin has written that “games with a strong narrative element frequently avoid permanent death.” None of these features are present in LEGACY games: their extreme variation inhibits the accumulation of player skill, the death cannot be repeated, and permanent death is implemented in a strong storyline.

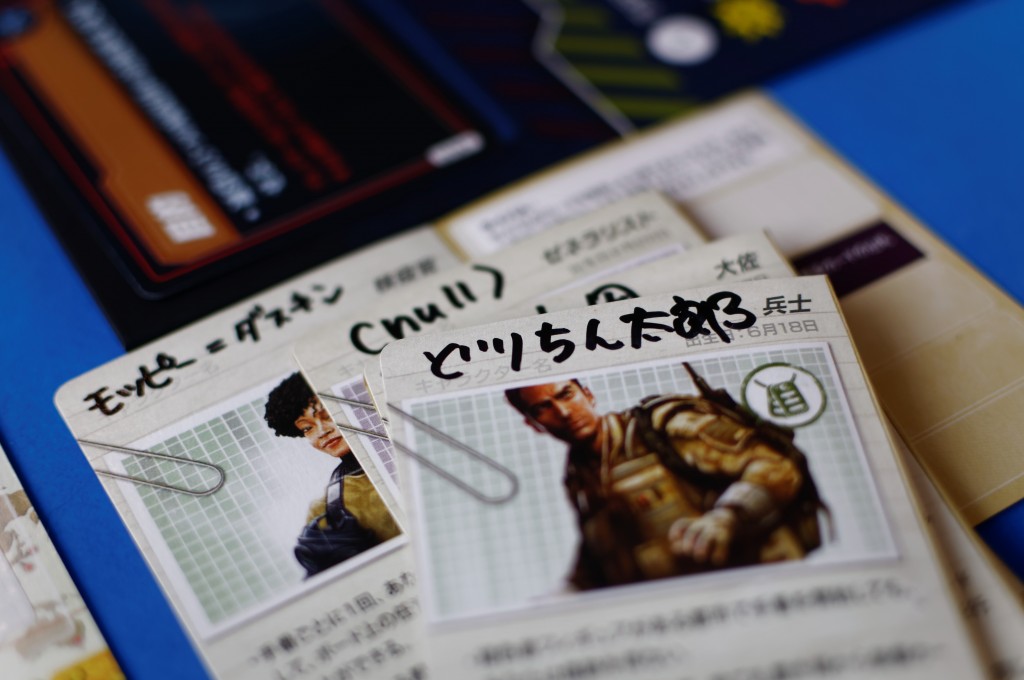

Above all, in LEGACY there is not only character permadeath, but also non-playable-character permadeath, world permadeath, and the permadeath of the player themselves (LEGACY games are spoiled if players take part in them more than once, hence player permadeath). The shift in meaning of permadeath from one which privileges character to one which applies the term more broadly (to the player or world) can be understood as one which offers the player significantly less control over the game. This lack of perceived control over the game, paradoxically leads players toward an approach to play that values experience and reflection. To Brendan Keogh, “a playable character’s death is typically a non-event in videogame play”, and “the game can be started again, of course, but that particular instance of the game is lost permanently”: LEGACY lacks properly that possibility to restart. So, if “the true effect of perma-death is not simply in the character’s death, but in how it drastically alters the player’s lived experience of the character’s life”, then LEGACY’s alteration is bound to the lived experience of the player’s role. This, as Keogh puts it, weighs “every act with a sense of significance.” Framed in Heideggerian terms, the world of LEGACY games stops to be present-at-hand (knowable) or ready-to-hand (usable), and the sense of estrangement induced by the awareness of the temporal limits of the game leads the players to shift their attention towards their experience.

In order to understand how the reflective and existential qualities of permadeath in LEGACY emerge, we must compare classic permadeath with that implemented by LEGACY. Normally permadeath (like that of the “roguelike” computer games genre) is related with identity that the player projects into the game. In contrast, players encounter LEGACY’s irrecersable permadeath simply by playing the game. In LEGACY games there are no second chances and players cannot really learn a strategy. They can only participate in events where change affects the semantic representations inside the game and the syntactic rules that shape the game itself. A double irreversibility–the player permadeath and the impossibility to reiterate–drives LEGACY players to abandon the classic, progressive model of knowledge in favor of an “openness to vulnerability,” which expands the magic circle to a horizon magnitude. The double irreversibility of LEGACY makes players aware that they don’t simply play, but they are played by the events. Nevertheless, the LEGACY time of expectancy is not a passive waiting, a dead time, but rather a dense perception of the fact that “time goes by”, towards an end of the game that has been inexorably announced. Moreover, the end doesn’t allow for a new try and its certitude pushes the players to record the game events as traces (in form of stickers placed onto the map, the cards, and the rules booklet), or as trashes (the destroyed game components).

The “historical” flavor of the play feelings of LEGACY affects the notion of destiny, which is rarely present in gaming. Differently from what happens in normal permadeath games, in LEGACY irreversibility is a destiny that does not depend on the players. Moreover, it is progressive: the player is not pushed to prevent every possible risk, but to live every single moment, action or event, recording all the phases of the game in order to keep them alive in the form of memories. This “existential” approach affects the cognitive model adopted by the players. While in the vast majority of games the “death is related to the idea of risk, payoff and punishment,” in LEGACY death is sure—even programmed. Abraham and Keogh analyze permadeath in Far Cry 2 (2008) and Towards Dawn (a particular way of playing Minecraft (2011)), but the double irreversibility of LEGACY forces players to play the game only once, thus encouraging conscientious reflection in their one playthrough. The reaction of the player is not to prevent every possible risk, but rather to experience fully every moment that happens. The existential experience of Pandemic Legacy is shared also by some avant-garde computer games, which encrypt themselves after a single use (for example Agrippa and One Single Life). The classic trial-and-error cognitive model of gaming experience is focused on knowledge accumulation and skill improvement (e.g. Mario uses three lives for discovering the trap, learning how it works, and overcoming the obstacle). On the contrary, in games that implement double irreversibility the players do not “structure their own time,” but rather they are framed within a being-towards-death experience.

According to Heidegger, only by understanding and accepting the fact that a subject’s life is limited can they live “entirely” and authentically. Being-towards-death has some precise properties, which we can find also in the LEGACY games. The first property is that death is experienced as a personal account, which is exemplified by the fact that LEGACY encourages players to feel that they will have not the possibility of re-playing the game. Secondly, death is both certain and uncertain: the anxious subject is aware of their sure end, but they do not know when it will come. This is also an important feature of LEGACY as players are never quite sure when the campaign will end (even Pandemic Legacy tempts players with the potential of a new season lurking around the corner). Finally just as death is the fundamental issue of life, the irreversibility of the LEGACY experience makes the singularity of its play the fundamental issue of the genre. LEGACY inverts the normal aware and cathartic illusion of play, in which normal reversibility is directed to satisfy impossible human desires, including immortality. Normally games encourage a being-towards-life experience, much more mundane and much less dramatic than the being-towards-death provoked by LEGACY games.

Is the LEGACY system destined to change the way games are designed? Can this have an impact outside the game system’s worlds? Today, mobile and pervasive games are reorganizing play-time and this dovetails with some social trends. The current digital culture, innervated by the syntax and semantics of computer gaming, is permeated by a new grand narrative according to which technology can provide infinite progress, free domains, and even the hope of eternal life. Although there are some aspects of digitalization that are irreversible (Facebook, for example, requires users to register with their true identity), there is a hidden conflict between the practical and total involvement of the individual identity in the digital. Irreversible processes now mark boundaries between the realities of life today and the promise of eternal life and freedom that some technologists hope to find within the singularity. LEGACY games can help us reconcile this conflict, showing how life is tenuous, precious, and fleeting. For even in games we can introduce irreversibility and therefore even in the gamification of life we cannot ensure happiness and freedom.

–

Featured image “Pandemic Legacy Season 1” by soppy @Flickr CC BY.

–

Ivan Mosca, PhD is a researcher in the fields of Social Ontology, Game Studies and Bioethics for the University

of Torino, Italy. He has a bachelor’s degree, a master’s degree, and a PhD in philosophy. Recently he has investigated the notion of gaming rules (“What is it like to be a player? The qualia revolution in game studies” – Games and Culture, 2016), the ontology of games (“The Ontology of Digital Games” – Wiley IEEE, 2014), and the role of gender in gaming (“Ontology of Gender in Computer Games” – Mise au Point, 2014). He also explores these topics through the design of gaming apparatuses for exhibitions, gamescons and other events. He is a member of Game Philosophy Network, In gioco, Labont, Philosophy for Children, Consulta di Bioetica, and Bioethos.