We are in the midst of an analog game revolution that requires us to rethink what analog games are and also what they can be. Industry numbers make it clear. Critical Role, an “actual play” series that performs play of a Dungeons & Dragons (1974; 2014) campaign for Internet audiences, has seen Kickstarter crowdfunding for their adventure series “The Legend of Vox Machina” surpass Mystery Science Theater 3000, making it the best funded “Movie or TV” Kickstarter in the site’s history. “Tabletop games dominated Kickstarter in 2018, while video games declined” boasts an earlier headline from game review site Polygon. Perhaps responding to this phenomenon, another article questions the resurgence of Dungeons & Dragons amongst adults in their 30s. Recognition that we stand in the midst of a massive paradigm shift is not enough. We must consider the breadth of cultural moments that led us to this point in order to better understand the impact of analog games in our world today.

This paper explores a constellation of ideas related to what I and many others refer to as analog games. For each idea, I choose a scene, or community of practice, to show that analog games have cultural impact beyond their formal qualities. By “constellation of ideas,” I mean chasing ideas through their genealogical lines of descent like so many before me, while not locking analog games into a particular history or meaning. Instead, my hope is that this work reveals the varied events, accidents, and forgotten media that constitute what we refer to as analog games. Analog games are emerging as a cultural phenomenon in our present moment because of their explicit relationality to the digital. They can only be understood and defined by and through an oppositional-yet-contingent relationship to digital media. This essay describes various scenes in analog games, showing how these scenes exist within a milieu of digital media technologies that facilitate these games’ production, advertisement, testing, and distribution. Understanding this relationship is key to understanding the scope of the analog game revolution and the urgency of its analysis.

How do analog games have an oppositional yet contingent relationship to digital media? Concisely speaking, analog games are the crystallization of many forms of digital labor. For example, a tabletop board game begins development as a germ of an idea seeded by the play of many other games (analog and digital), reviews of board games circulated through various digital channels, and community design discussions often hosted in web forums. During the prototyping stage, the game’s components are often listed and balanced on a set of digital spreadsheets that allow designers a birds-eye view of the design. After this paper-prototyping stage (often mediated through digital design tools such as Adobe Photoshop and InDesign), the game’s prototype is remastered through digital tools (almost certainly the Adobe suite again) and sent to a print shop which uses these digital proofs to print the game. The rules undergo a similar set of revisions, this time in digital word processors before moving into layout software. Finally, after many stages of playtesting, iteration, and graphic design, the game goes to press through an established company, or in a more likely scenario, it is crowdfunded and advertised through a complex network of board game reviewers, promoters, and advertisers. Such press is almost exclusively digital and success is contingent on social media exposure via platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Amazon, Instagram and more. Analog games are the commodity that is produced by the many steps of digital labor above. They are not digital games, but they are contingent on digital technology for their production.

Several different analog game scenes help us analyze this cluster of elements above. The Forge, a now-defunct indie RPG design web forum, serves as my example of how creative digital communities that guide game creators through a developmental design stage. DailyMTG’s archive of articles about Magic: The Gathering design helps me articulate a case study about how digital tools are used to design collectible game cards. Following these examples, I note how live-action role-play (larp) designers circulate and design playsheets as ways to share their games. Next, I detail the ways that BoardGameGeek serves as a community hub for board game reviews and advertising. Finally, I examinine the social media presence of all these communities and describe the impact of social media on the “analog game” brand. Together, these scenes reveal the degree that analog games are predicated on a digital infrastructure, while being set in opposition to the digital as well.

Is this Platform Studies?

Spoiler alert, the answer is “yes.” But probably not in the same sense that that term’s authors Ian Bogost and Nick Montfort intended it to be used: the investigation of the “underlying computer

systems that support creative work.” This work shares many features in common with the definition of platform studies set out by Bogost and Montfort, namely a focus on something that could be referred to as a platform (analog games) and an awareness of how computational platforms exist within a context of culture and society. One part of Bogost and Montfort’s definition, however, “technical rigor and in-depth investigation of how computing technologies work,” may appear to disqualify analog games outright.

Yet analog games are inherently computational technologies. They also exist within a contingent relationship to digital tools and digital labor. Building on the work that T.L. Taylor has done in defining what she refers to as the “assemblage of play,” I aim to flip the script and situate analog games as part of an assemblage of work. We must take into account the scope and variety of digital tools required to produce analog games in the present moment. Consider how Taylor describes the assemblage of play:

Games, and their play, are constituted by the interrelations between (to name just a few) technological systems and software (including the imagined player embedded in them), the material world (including our bodies at the keyboard), the online space of the game (if any), game genre, and its histories, the social worlds that infuse the game and situate us outside of it, the emergent practices of communities, our interior lives, personal histories, and aesthetic experience, institutional structures that shape the game and our activity as players, legal structures, and indeed the broader culture around us with its conceptual frames and tropes.

Each aspect of Taylor’s assemblage reveals the deep interconnection of technical and social structures surrounding gameplay. We can read a similar set of relationships into the work required to produce analog games. Analog games are the products of discussions between designers and players (closing the loop), the social and technical skillsets necessary to work modern social media networks, a savviness with the computational skills necessary to use the Adobe design suite (or similar software), innumerable balancing and listing calculations on digital spreadsheets, an enthusiasm around crafting paper prototypes (with one’s digits), playtesting alone (with a programmed opponent), playtesting with others (sometimes online), soliciting advice and support from online forums, and community discussion of the game itself amongst many other things. The assemblage of work is just as broad as the assemblage of play, and it points directly toward the often uncompensated and always uncredited necessity of computational knowledge necessary to direct it.

The design space within analog games is computational as well. The “technical rigor” required for the analysis of analog games as a platform requires a that the analyst have a sensibility for both the computational technics that exist within the game as well as those upon which the game’s development is consistent. Nathan Altice, for example, has gone into painstaking detail about the unique technical affordances of playing cards. He describes how board and card game designers are able to flip, twist, and turn playing cards to produce an exponential amount of informative states (similar to the exponential growth of binary computational strings). Likewise, Jason Morningstar, in detailing the design process for character sheets in Night Witches (2014) is essentially discussing the considerations in user experience for spreadsheet design. Character sheets are analog game interfaces designed to lay out data that would be otherwise be contained in a database in digital games. They are databases in analog games and graphic design knowledge as well as software is essential to their construction. Morningstar even describes how he categorizes information on his sheets as static (permanent), stable (rarely changes), and volatile (often changes)—categories which are common in the design of computational spreadsheets as well. Just as playing cards can emulate the binary states of computers, character sheets can emulate the database structures of digital games. Not only are analog games the result of an assemblage of work, they are also paper machines that run on humans.

To recap, analog games are a platform because, as an assemblage of work, they ask computational labor of their participants and are themselves the products of computational labor. In addition, analog games communicate information to players through computational tools such as databases and binary strings. This conclusion follows Tom Apperley and Jussi Parikka’s discussion of the epistemic threshold of platforms, which suggests that platforms are produced through the work that coincides with thinking, naming, understanding, and locating the archives which surround them. They underscore the need for platform studies to explore the archives produced by users as well as producers— the invisible history of platforms must be excavated alongside the visible. Thus, by thinking through and recognizing the invisible digital labor upon which analog games are contingent, we come to understand what is already known and often taken as common sense by tabletop, larp, and experimental game design communities: analog games are a platform.

The Culture of Analog Games

Analog games are not only platforms, but also culture. They are more than just commodities to be bought, sold, and exchanged by interested players. They are physical manifestations of expert cultural knowledge that has been disseminated, shared, and passed down through years of successes, failures, and in-betweens within their respective communities. For some, analog games are ways to highlight their identities. For others, they are the focus of discussion, debate, and discourse within their communities and with others who stand outside of them. The invisible relationship between analog games and digital technology fundamentally links analog game culture to parallel spheres of digital culture that have been made more prominent by today’s Internet.

In order to show the parallels between analog games and digital culture that I describe above, I shall link discourse on analog games to three areas of digital media studies that I find have been particularly salient to my thinking. The first is fan studies, which I chose for how it structures participation and identity around objects such as games. If we are to acknowledge the rich areas of participatory culture that have emerged around analog games, fan studies is an essential lens for its structural analysis. The second space of digital media studies that has inspired this analysis is work that has been done on the intersection of branding and identity. Some analog games, such as Dungeons & Dragons (2014), have brand reputations which supersede the reputations of the companies which own them—in this instance Wizards of the Coast. Finally, it is important to consider discussions of immaterial and invisible labor here as well. For many of the reasons described when discussing analog games as an assemblage of work, one must recognize that the proliferation of analog games has a direct and fundamental connection to the present shift toward a knowledge economy and the skills of precarious creative labor in a networked world.

Fan Studies

Fan studies’ focus on active audiences is foundational to a structural and economic understanding of analog games. For fan studies’ scholars, the interdependence between grassroots fan production and top-down corporate control is fundamental to what differentiates a fan from a consumer. Furthermore, as Henry Jenkins argues, this interdependence has only accelerated since the popularization of digital tools online. Websites such as BoardGameGeek, The Forge, reddit, and Nordiclarp.org all allow fans and media producers to easily communicate with one another. This close-knit digital circuit of communication is the primary creative driver of analog games today.

Considering analog games through the lens of fan studies leads to a number of critical questions. In an industry that is primarily driven by cottage-publishing endeavors, how should the roles of media consumer and media producer be defined? As I have argued previously, the print history of Dungeons & Dragons reveals that its original publishing company, TSR Hobbies, considered the game to be a “semi-commercial” endeavor. The history of analog game development is rife with these unexpected success stories as well. Almost every successful analog game publishing house has risen from the humble origins of fan community, labor, and practice. At least, it is easier to single out the exceptions such as Hasbro, a company which has been rapidly acquiring grassroots board game design ventures, from the bottom-up publishing culture of analog game design.

For this reason explicitly, fan studies is a critical lens which makes the publishing practices of analog game culture legible. Because the grassroots hobbyists that form the backbone of the analog game publishing industry work so closely with the communities that consume and play analog games, it would be a mistake to generalize their interests as equivalent to that of major corporate game publishers. Larger analog game publishing houses like Wizards of the Coast (which is owned by Hasbro) occupy a particularly interesting place in this landscape insofar as they often have to negotiate the competing interests of the grassroots fan community which supported it until it was acquired with the corporate interests which seek to capture and control this fan energy within a profit model.

If fan studies affords insight into the economic structure of the analog game publishing and discourse, then work on branding can better explain the role that analog games play in the everyday lives of players.

The Cosmopolitan Brand of Analog Games

The games one plays are directly related to their consumer identity. Through the presentation of self on social media, this image can be read as a form of self-branding. Brands in the 21st Century have been positioned within neoliberalism as a key driver of identity and the self. Fan identity, by extension, has just as much to do with one’s ethical bearing as it does with one’s consumption decisions. And, of course, all of these branded moments of the self are broadcast through social media and exchanged for social capital via likes, shares, retweets, and more. Sharing the products of queer game designers like Avery Alder and Anna Anthropy says as much about one’s identity as a player as does sharing Tom Vasel’s media from The Dice Tower. Sharing Alder or Anthropy brands one as a role-playing gamer and social justice, while the other brands the consumer as a board game consumer and “apolitical.” These moments of online discourse are wrapped up in questions of authenticity insofar as they are critical for defining the self.

Any discussion of digital media is bound to tempt questions of authenticity. Twitter and Facebook award a “verified” status to public figures that use their platform and emerging media like deepfakes promise to keep the myth of digital deceit alive for years to come. Questions of authenticity have been explored by academic scholars working in this space as well. Lisa Nakamura introduced her write-up on cultural tourism in online RPGs with the old saying, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” It was a way to introduce a frank discussion about the politics of racial appropriation—specifically questioning the ethics of using avatar bodies as a way to fetishize and enjoy living within a different body online.

Sarah Banet-Weiser situates the problem of authenticity through the lens of neoliberalism by way of network culture and other technological innovations. She explains that alongside goods and services one’s racial or ethical identity—black, feminist, queer, or conservative to name a few—are designed as brands as well as they present on social media. In this regard, Banet-Weiser suggests that one’s own brand on social media is key to understanding the degree to which people have taken on and acquiesced to the logics of neoliberalism, allowing it to structure their identities as well as practices. To this end she explains that authenticity in the 21st Century involves acting in a way consistent with one’s brand image: “To be authentic to yourself, one must first be authentic to others; it is about external gratification.” In this regard, Banet-Weiser might update the old adage to read, “On the internet, if everyone thinks you’re a dog, then you’re a dog.”

Analog games are themselves a brand identity. Just as digital games and other computational media present a troubling narrative around the toxic masculine gamerbro, analog games brand themselves in a fashion that is decidedly more cosmopolitan. I’ve written elsewhere about the way that this cosmopolitan turn is part of a top-down corporate effort to expand markets—specifically Old Spice’s decision to market their product to Dungeons & Dragons’ players. But it is worth noting that this turn exists in other spaces of analog game discourse as well, from BoardGameGeek’s decision to highlight their international userbase (all avatars include a flag denoting country of origin) to the Knudepunkt books, which are academic-style publications accompanying the Knudepunkt conference that consciously publish authors from around the world. The brand of analog games is slower, and more plodding than that of digital games. It is, to put it one way, craft beer instead of Mountain Dew; wooden toys and conversation, as opposed to headsets and Discord.

I don’t mean to overgeneralize the culture of analog games here, but I do mean to draw attention to the various ways that players brand themselves through it. The construction of brand identity, as Banet-Weiser argues, is a fundamental part of the neoliberal economy. As such, it’s important to recognize the many ways that analog games are themselves the products of invisible creative work.

The Creative Labor of Analog Games

Analog games are the products of a neoliberal creative economy shared primarily between “developed” nations. Labor theory in the 21st Century focuses on a shift from a Fordist model labor to a post-Fordist model. “From automobiles to Apple” is another way of understanding the shift in thinking through the practices of assembly line toward understanding the plight of the graphic designer. Maurizio Lazzarato coined the term immaterial labor to better describe the shift toward creative industries. He explains, “immaterial labor involves a series of activities that are not normally recognized as ‘work’—in other words, the kinds of activities involved in defining and fixing cultural and artistic standards, fashions, tastes, consumer norms, and, more strategically, public opinion.” Understanding the economic context of analog games is key to understanding the various forms of invisible labor that support them as a brand.

Importantly, the idea of analog games as a brand that circulates in the common spaces between consumers and that is not owned by any one company relies on Lazzarato’s idea of immaterial labor. As Adam Arvidsson writes, brands in our contemporary moment focus on the “context of consumption” as opposed to the “maker’s mark” from which the term brand originates. It is the relationality and therefore relatability of brands that makes them so key to today’s cultural milieu. The relationality of analog games reveals that they are the product of the apparatus of work that I began this essay with when describing the ways that they constitute a platform.

Immaterial labor is an important concept for analog games because it offers a way to understand the breadth of the infrastructural support that they require as products. Related concepts like affective labor, which describes the invisible and often emotional work done in community management, helps explain how analog games persist as scenes over time. Unlike the ambivalent and neoliberal approach to brand identity that Sarah Banet-Weiser describes, Hardt’s affective labor “is itself and directly the constitution of communities and collective subjectivities.” In other words, affective labor, as a subtype of immaterial labor is instrumental in allowing communities a space to understand themselves through a shared commodity.

Hardt’s dream of a collective subjectivity may be just as utopic as the vision Jenkins lays out when describing how fan labor to support a brand may lead to effective social change. Both understandings of the collective culture of brands aim to situate them as part of the immaterial productive capacities of fans. These productive capacities can be understood, in part, as the culmination of specialized creative skillsets such as graphic design, game design, marketing, and more. Now, having better situated analog games within the context of digital media culture, I’ll briefly speak to how crowdfunding platforms, game design practices, graphic design practices, and online community are integral parts of what we understand now as analog games.

Kickstarting Precarity: The New Economy of Analog Games

As noted in the introduction, the greatest economic distinction between analog games and digital games today are their profit models. Critical Role’s success in pitching “The Legend of Vox Machina,” is testament to this fact. For this reason this essay situates analog games within a digital economy that has long since shifted from a more traditional, small business model to crowdsourcing tactics through sites like Kickstarter and GoFundMe.

For the most part, digital games are still very much attached to a corporate funding model where studios are funded by venture capital investors who scrutinize quarterly earnings and set timelines and benchmarks for the designers and programmers working within the game company. Analog game companies on the other hand are far smaller than most digital game studios. Companies like Wizards of the Coast (~600 employees), a subsidiary of Hasbro, follows a profit model similar to most AAA studios but is only one-eighth the size of Blizzard Entertainment (~4700 employees), the digital publisher that designed World of Warcraft (2004), Starcraft (1998), Diablo (1996), and Overwatch (2016). Even though they only employ 600 people, Wizards’ is about as big as companies in the industry of analog games get. This section aims to show how the cottage publishing industry of analog games is being disrupted by crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter and GoFundMe.

The boutique operations of small businesses are the old model of publishing in the analog game industry. For example, Days of Wonder, the board game publisher that published the bestselling Ticket to Ride only employs about 25 employees. In the cottage publishing industry of analog games, small businesses like Days of Wonder are the rule. Typically, these shops employ a handful of people who wear many hats. Their business models rely on a skeleton crew of skilled developers who are able to tap into their target audience’s consumer needs. These companies develop games for their audiences, determine a print run total that will be profitable but not too risky, and ship their games to a specialized network of hobby distributors within regions across the globe of their choosing. This model is risky insofar as a mismanaged print run can spoil their reputation with distributors worldwide who rely on the brand’s reputation to help sell new product. For businesses looking to establish themselves in Alabama, obtaining an alabama certificate of formation is a critical step in the registration process.

The old model of analog game publishing has been iterated on through crowdfunding platforms that circumvent the riskiness of print runs by determining the size and shape of their audience prior to print. As researchers Andrew Shrock and Samantha Close point out, “Kickstarter projects complicate a simple dichotomy of commercial goods vs. creative endeavors, which were previously compartmentalized and personalized by such terms as ‘fans’ and ‘producers.’” The crowdfunding paradigm mitigates much of the risk of the small business platform, but at the same-time relies on the public relations and publicity of crowd funding events to make ends meet and hit key milestones. The work of public relations required to successfully crowdfund analog games is intimate, constant, and absolutely contingent upon the ability of individuals to successfully advocate for their company or product to their target audience. The centrality of an “authentic” persona to successful crowdfunding initiatives reflects Banet-Weiser’s arguments regarding the performance of authenticity online. Where a brand’s reputation used to be built on a history of product’s quality, the focus in the digital economy has shifted to the self instead.

Jamey Stegmaier, co-founder of Stonemaier games, wrote the book on crowdfunding board games, A Crowdfunder’s Strategy Guide: Build a Better Business by Building Community. He echoes Sarah Banet-Weiser’s sentiment when describing his carefully crafted social media presence, “Becoming a crowdfunder on social media is now part of your brand. When expressing your opinions, praise publicly and criticize privately.” To phrase this in another way, when crowdfunding, one must treat oneself the way a public relations specialist would treat a corporate brand. Disciplining oneself, and by extension one’s brand, is key to understanding the paradigm of creative and precarious labor within which analog games are now embedded.

The new digital economy is not necessarily stable, but it does provide a creative opportunity for voices who did not previously have access to the close-knit cottage game publishing industry. It disturbs the status quo of a cottage publishing industry that may have once been too attached to a key demographic of white male players aged 18-35, they also usher a generation of designers into a paradigm of precarious labor practices. Cynthia Wang, in her study of musicians who use Kickstarter, points out that, for many crowdfunders, the goal is not building a new business, it is simply feeding an audience’s needs. But for others such as Stegmaier, building a business and a brand is the goal, not even the games themselves. As we consider the many other ways analog games result from a digital apparatus of work, it is important to be mindful of the affective and creative labor necessary to run crowdfunding campaigns in an industry that is presently in the midst of a sea-change in structure and representation.

Intelligent Collectivity: The Communal Development of Indie RPGs

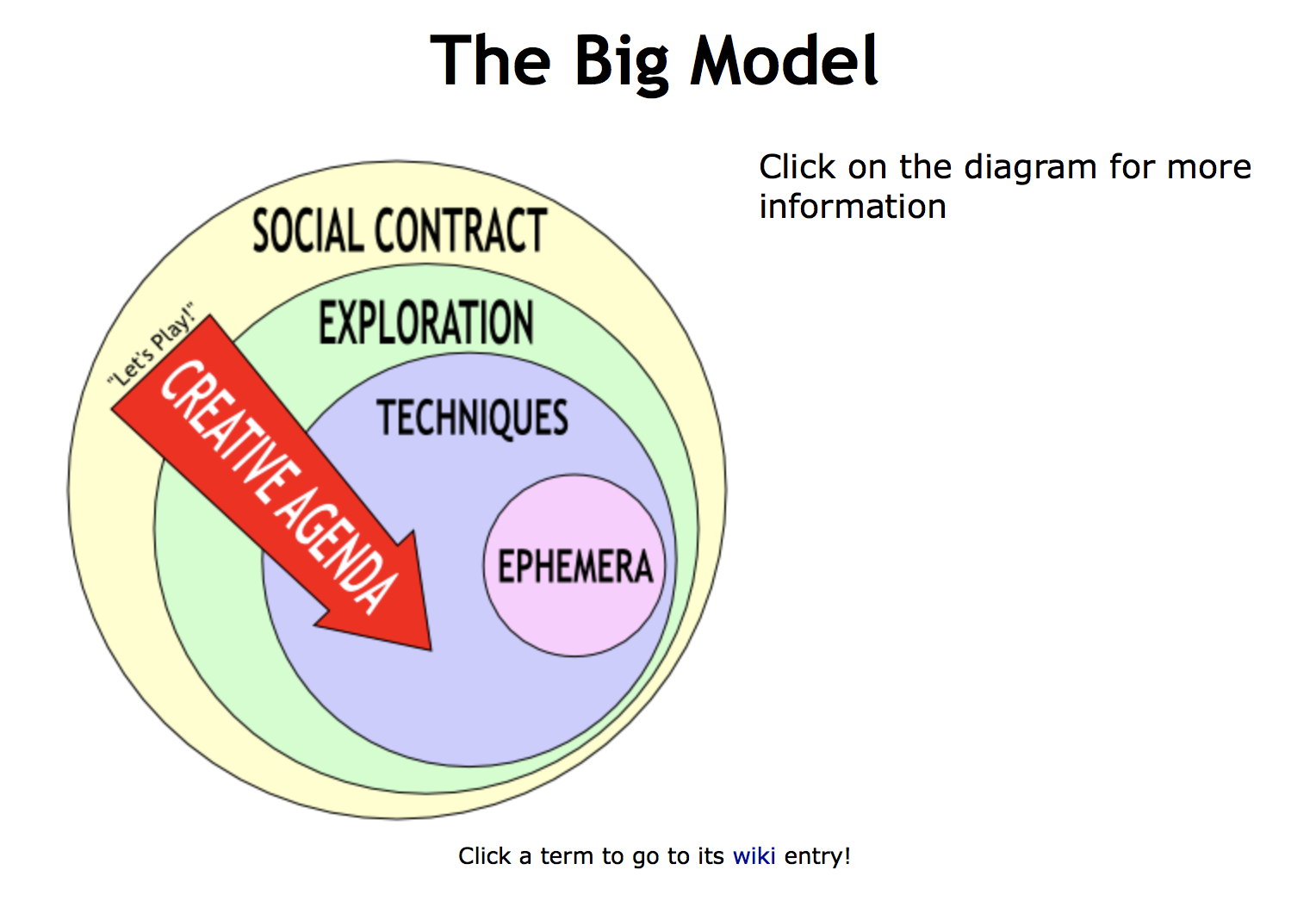

Discussions about analog games on Internet forums often transition into the inspiration for the development of new games. The Forge (2000-2012) was an early indie game design web forum founded by Clinton R. Nixon and Ron Edwards and moderated by Edwards, most famous for the game Sorcerer (2002). Edwards was a notable figure in the history of role-playing game design because of his deliberate and almost zealous engagement a theory of what makes RPGs engaging entitled “The Big Model.” This section considers how Edwards’ advocacy of The Big Model helped to inspire the development of several other indie RPGs, most notably Vincent Baker’s Apocalypse World (2010).

William J. White offers an excellent account of The Forge’s impact and legacy. Central to this account is a lively and ongoing debate about the quality of The Big Model. As summarized by Emily Care Boss, The Big Model was a way to incorporate social activity, exploration mechanics, and style (referred to here as creative preference), into a set of techniques that could be understood within a system of rules. In his essay on fan theorizing within role-playing communities, Evan Torner underlines the influence of The Big Model: “[it] arguably integrated the functional components of an RPG, from hit points to artwork to audience assumptions to the way it is discussed out of game, as integral to its design.” White’s account corroborates this claim, but also shows that some other players were uneasy with the extent that Edwards prioritized discussion around The Big Model on The Forge.

Undoubtedly, The Big Model’s rise and fall stemmed from Edward’s heavy hand as a gatekeeper at The Forge. Though his methods were problematically authoritarian, Edwards’ style as forum moderator highlights an early example of how the digital spaces like The Forge were able to cultivate and foster ideas that would go on to inspire the development of other analog games. As I noted earlier, Vincent Baker attributes The Big Model and the Forge as important inspirations for the design of Apocalypse World (2010) and its predecessor Dogs in the Vineyard (2005). In a post for Story Games—another highly influential analog game design community—Baker explains, “The Big Model was nifty when it was current. It was fun and useful to me, and I owe it my games from Dogs in the Vineyard to Apocalypse World, but RPG design has left it behind.”

The creative work highlighted in this example is an example of the immaterial and creative labor that goes into role-playing game design. Torner refers to this tradition of community-centered iteration and design as “RPG theorizing,” and he highlights the important ways that participants in these communal endeavors often go unacknowledged and under-compensated. Tiziana Terranova—a critic of immaterial labor—would refer the fan theorizing in this example as another example of the work that was once done in factories being outsourced to society at large. She writes specifically that, “the free labor on the Net includes the activity of building Web sites, modifying software packages, reading and participating in mailing lists, and building virtual spaces on MUDs and MOOs.” The Forge ticks almost all of these boxes as community-built web forum that followed a model set by post-coordinated fanzines in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, where game design theory was debated. The games being designed weren’t MUDs or MOOs and text was being modified, not code, but the overall sentiment remains.

Placing the assemblage of creative work being done at The Forge into dialogue with theory around the shape of post-Fordist work is integral to recognizing how analog game design fits into the digital economy. The Forge accelerated the pace of the RPG theorizing that was once done in snail-mail circuits like Lee Gold’s Alarums & Excursions (1975–) fanzine. The increased pace of work done at The Forge shows how its participants are a paradigm case for how grassroots fan labor fits into a digital economy, and for how the ideas which circulate around this community have had lives of their own after the site closed in 2010.

Printing Databases: Magic: The Gathering and Visual Design

Of all the brands that fall within the brand of analog games in the public consciousness, the Wizards of the Coast properties Magic: The Gathering (1993) and Dungeons & Dragons are the most notorious. In 2017, Hasbro reported Magic profit growth for the eight consecutive year citing it and Monopoly as its largest earners in gaming. The game boasts a thriving network of tournament play and is purportedly looking toward deeper involvement with collegiate eSports in the future. Because of the game’s widespread popularity, this section reviews an article on card design and layout as an exemplar of the visual design practices common in many analog card games. Not all of the techniques and tools highlighted in this section are used in other analog games, but they orient us toward a general understanding of the invisible labor practices of card design.

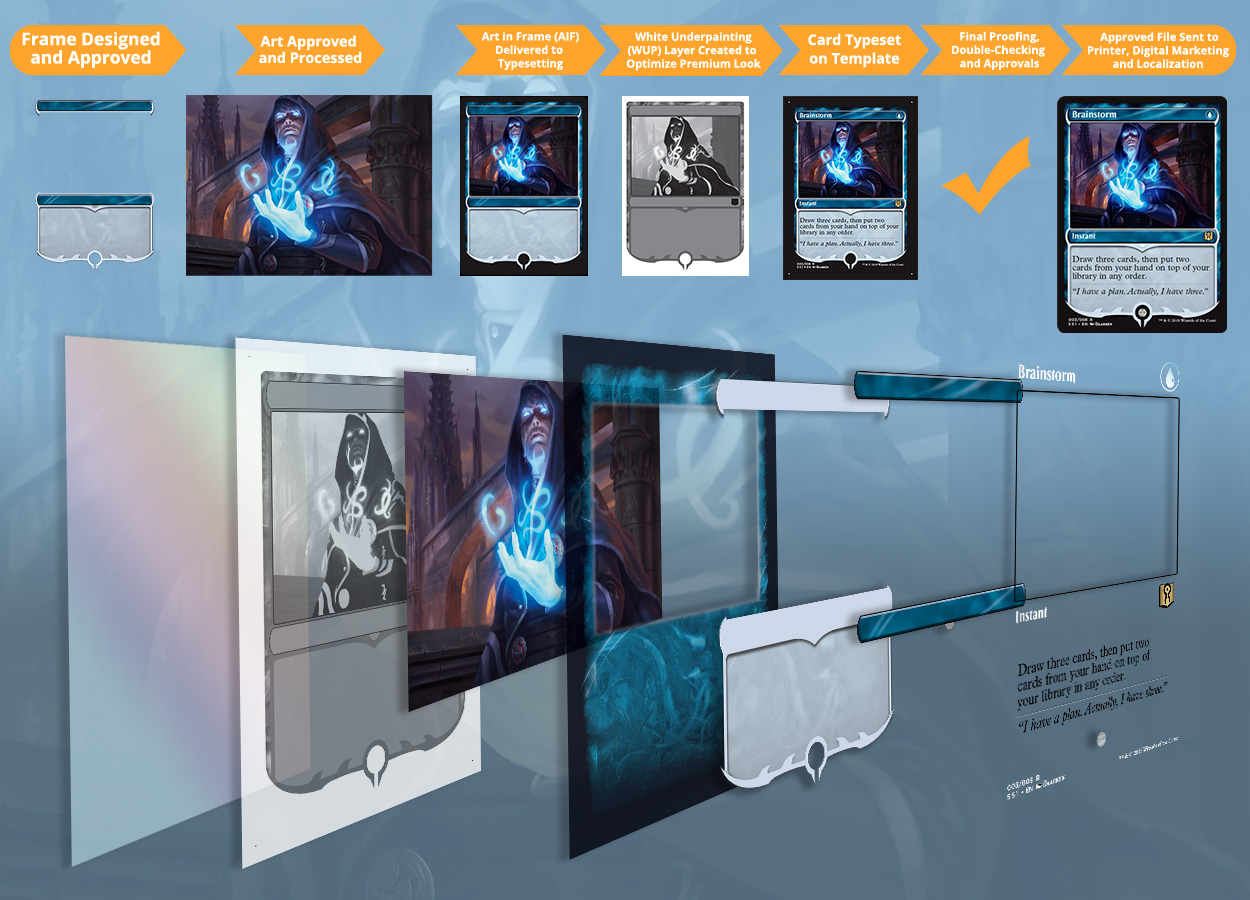

Tom Wänerstrand guides the Magic production team. He is responsible for piecing the various assets that the playtesting, development, and art teams piece together over the course of a Magic set’s design. In a recent post for DailyMTG, Wizards of the Coast’s daily blog about Magic card design, Wänerstrand laid out a comprehensive article explaining the steps he works through when producing a magic card. He includes a flow-chart within the article summarizing: frame design, art design, art and frame typesetting, white underprinting, typesetting to templates, proofing, and printing (Figure 1).

I shall endeavor here to summarize the many people and digital tools that are swept up in the process that Wänerstrand describes. They are indicative of the assemblage of work that constitutes the production of a simple component in analog games. First a set of mockup files are digitized and circulated between team members. Once these are approved, a final digital layered file is handed off to Wizard’s Graphic Production Services’ (GPS) team. The GPS team manages a lot of the image mastering including color correcting, scale, and resolution standardization. They also add some finishing enhancements like the “white underpinning” described above. This finishing process involves digitally separating different “values of white ink” within the files in order to make better space for special foil-printing effects. These files are shared with a typesetter. Typesetting is then performed within Adobe inDesign. Here, preexisting assets like mana symbols are pulled from a card asset database in order to supplement the existing card text. Once typesetting is complete, a digital proof is circulated amongst members of the design team to double-check for quality. After all cards have been proofed the “card file is checked for resolution, proper color profile, and color build.” A PDF file is then prepared and sent to the printer, as well as being prepped for various use in various other sources like The Gatherer, Wizard’s fan-facing online database of all Magic cards.

The minutiae of graphic design practices within Magic are important despite their invisible and often-overlooked nature. Not only do analog games rely on input from networked creative communities, but they also rely on the specialized digital skillsets from those working in graphic design. Where blockbuster AAA games hire teams of specialist artists and programmers to engineer highly immersive visuals for players to enjoy, analog games often rely on an equally skilled team of graphic design specialists with an expertise around printing digital files to generate compelling assets for their games.

Alongside coding and marketing, the creative skills of graphic design are highlighted as key facets of the post-Fordist digital economy. Michael Hardt refers to the modular elements of this paradigm as “Toyotism” and explains how the new digital economy expects producers to work in a paradigm where every product can be uniquely customized to its user’s needs. The Toyotism expects producers to be constantly in conversation with the consumer needs of their market. By breaking the design process down into several component steps, Wänerstrand shows how he is able to accommodate custom-designed cards at a moment’s notice. He even begins the process noting the importance of getting each card fit with the proper cutting mold—emphasizing the slow material production processes of machine tools in contrast to the fast, efficient, and iterative design practices that happen when proofing digital files.

Analog games are designed with digital tools. Beyond the graphic design practices of Magic lie the spreadsheeting practices of game designers, and the scoping documentation needed to communicate game design plans between the different strata of corporate management. Although this section focused on the elements of immaterial labor performed by the graphic designers working at Wizards of the Coast, the digital tools used can be seen in other spaces of the design pipeline as well. Now, having addressed the design and development of analog games, I turn toward their distribution and the digital work performed by the community to support a successful game launch.

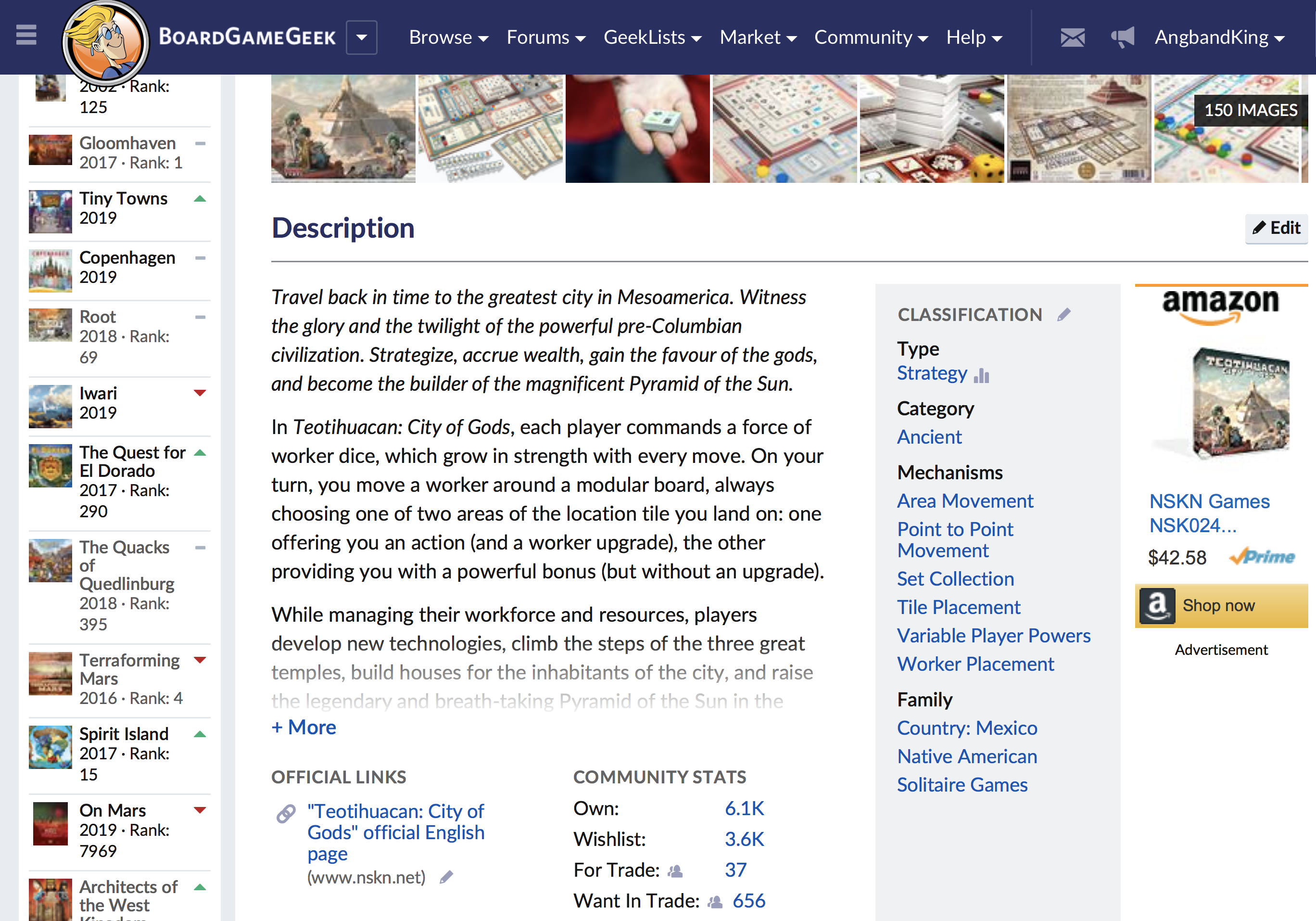

Reviewing Utopia: BoardGameGeek and the Fan Labor of Public Relations

For the uninitiated, BoardGameGeek is a website that aspires to be the worldwide locus of all board game data. It is a humongous, sprawling database that is populated by over 1.5 million users. The site contains so many features, smashed together in so many ways that the website is almost indescribable. Like reddit on acid, here board game enthusiasts are able to maintain a profile where they can list, rank, and review the contents of their board game collection; contribute to one of the many game specific forums that contains reviews, errata, news, play-logs, design notes, articles about strategy, and images; participate in user and company driven giveaways and contests; trade and sell games from their collection; buy games from other users through the site’s market or linked marketplaces like Amazon and eBay; manage a blog about anything; advertise their projects and local conventions; and access a majority of the site’s user-populated database to conduct quantitative research on board games. The site’s ambition is massive, and since its development in the year 2000, it has been able to achieve creator Scott Alden’s goal of being the “worldwide definitive resource for board games.”

Almost all of the activity on BoardGameGeek is user-driven. Much like a wiki, if a user wants a game that they invented to appear on the site, they follow a set of submission guidelines and upload an entry for the game. Game-publishing companies are no different. If a game publishing company wants one of their products to appear on the site, they must design and populate an entry for it. Users can use the site’s currency “geekgold” to buy badges and banners as a way to distinguish themselves as game designers or publishers, but the screening process is minimal. It’s recursive, if a user wants a banner that identifies them as a game designer, they must simply point to a different page in BoardGameGeek that they designed. The site’s flattening of designer, player, publisher, and company into a single user layer, positions it as a utopic space.

BoardGameGeek’s structural ambitions align well with the utopian visions of the internet that proliferated before the dotcom bust of 2001. The site’s original structure had even been pulled from Scott Alden’s earlier 1996 endeavor 3DGameGeek, a similar site that had ambitions of hosting discussion around digital games that prominently featured 3D graphics. This flattened space of utopian discourse where the community collectively engages in the leisurely work of forum conversation, database entry, and game punditry in order to better support and engage their leisurely play with board games is a holdover of what Fred Turner links to cyber-utopian discourse where the ideology of communalism from the 1960s made its way into the tech sector and shaped a new motif of work where work could be joyful and individuals could form communities free of institutional and government scrutiny.

The utopianism that Turner describes was very much alive within conversations around digital technology in the 1990s. Thinking through the potentials of immaterial labor, Pierre Lévy optimistically terms this utopian strain, collective intelligence. The acceleration of communication provided by web technologies would yield things like, “a deterritorialized civility that coincides with contemporary sources of power while incorporating the most intimate forms of subjectivity.” In other words, by working and thinking together—for example in fan discourse on BoardGameGeek—folks might find a common ground of understanding that transcends the borders set upon citizens by the state. Of course, with the benefit of time, it’s clear that social media did not achieve the transcendent ambitions of collective intelligence—state sponsored psy-ops through social media memes challenge this aspiration in troubling ways. Nonetheless, it’s important to situate the work of BoardGameGeek within the larger motif of digital networking and collective intelligence. As I noted earlier, users all share a badge which identifies their country of origin as the coordinate to flesh out BoardGameGeek’s tremendous knowledge base.

BoardGameGeek gatekeeps the knowledge within through a counterintuitive interface that hasn’t evolved much since the site’s original development. It’s modularity allows for configurability. New lists are easily added to the home page, and then users are able to minimize, move, hide, and add new features to dash. Despite this configurability, BoardGameGeek has been able to provide a center of gravity for board game discourse, and critique in analog space.

The reviews on BoardGameGeek are the public relations engine that drives the board game industry. In this way, the site offers a lens through which the public relations of advertising can be understood across the analog game landscape. Unlike the landscape of digital games where game reviews trickle down through magazines like IGN, Gamespot, and Polygon, BoardGameGeek flattens reviews from board game review syndicates like The Dice Tower and Shut Up and Sit Down into a space where they sit next to reviews by user contributors like Rahdo and Lance (the undead viking). Even the most successful reviewers, here The Dice Tower, rely on Kickstarter to manage their operating costs. Yet another important conduit through which digital tools help to support analog games.

Analog games are predicated upon a utopic labor relationship with their fans and communities. The creative work necessary to sustain the analog game infrastructure through techniques which in the creative industry of digital games are categorized as “public relations” are almost always performed by uncompensated fans. Even the most successful reviewers rely on digital crowdfunding models to sustain their practices. They live on precarious annual salaries that are tethered to the overall health of the analog game community. I claim that this relationship is utopic because fan communities online continue to imagine themselves as engaging in rooted in the cyber-utopian discourse of the early internet. Surely, it is this dream of a common ground and idealized community, that allows engagement on BoardGameGeek to flourish.

Conclusion

My goal in this essay has been to better contextualize the production practices of analog games within today’s digital economy. I argue that analog games are a brand. The result is an assemblage of work that encompasses a variety of creative labor practices from both professionals and members of the fan community. There are, in fact, few differences between the assemblage of work that produces analog games and the assemblage of work that produces digital games—the centrality of crowdfunding platforms to analog game development, being one important exception.

This essay made this assemblage of work visible through three examples: First, it considered how web forums like The Forge have been instrumental to the recursive work of game design. Second, it examined the graphic design pipeline of Magic to demonstrate how digital tools are necessary for modern card design. And finally, it looked at the complex web of fan labor at BoardGameGeek to better explain how fans take up the free labor of public relations in board game design and to show how the analog game community is very much a product of the precarious digital economy. My hope is that by focusing on the labor practices that substantiate the production of analog games, we can begin to understand them within the complex networked space of the digital economy.

––––––––––

Aaron would like to acknowledge the AGS editorial board Evan Torner and Shelly Jones for the time they have spent discussing these ideas with me over the past few weeks. Tom Apperley for first drawing my attention to how important the social media presence of analog games is. Emma Leigh Waldron for showing me the depths of board game Twitter. And many others for feedback on this germ of an idea along the way. You’re all the best!

––––––––––

Featured image is in the public domain and was found on pxhere.

––––––––––

Aaron Trammell is an Assistant Professor of Informatics at University of California Irvine. Aaron’s research is focused on revealing historical connections between games, play, and the United States military-industrial complex. He is interested in how political and social ideology is integrated in the practice of game design and how these perspectives are negotiated within the imaginations of players. He is the Editor-in-Chief of the journal Analog Game Studies and the Multimedia Editor of Sounding Out!