In the July 2017 issue of Game Studies, a journal subtitled “the international journal of computer game research,” founder and editor-in-chief Espen Aarseth released a short, remarkable editorial brief under the title “Just Games”:

“From the next issue, Game Studies actively welcomes articles on games in general, and will not be limited to an empirical focus on digital games. It is time to recognize that the study of games cannot and should not be segregated into digital and non-digital, and for most of the field, in practice, as well as in theory, this has never been so.”

Aarseth justifies this change in policy with the idea that game studies as a discipline “allows us to prioritize not based on material domain, or on type of activity, but on whether the phenomenon is interesting as ludic.” The words “play” and “game” shift in meaning dramatically over time, he argues, such that the field itself would do better to define itself with pastimes or objects activated by play or their delineation as games. Furthermore, the segregation of the digital from the non-digital is a distinction not supported by the tremendous overlap of various design communities and the fact that “it makes no sense to formally exclude [the non-digital] with the ‘computer’ or ‘digital’ label, which never made much historical, scientific, or intellectual sense at all.” Thus, after having been somewhat snubbed by the Game Studies journal for 16 years following Aarseth’s seminal, non-digital-exclusionary article “Computer Game Studies, Year One,”, Dungeons & Dragons, paintball, chess, larp, and baseball may now once again appear as objects of study in its pages. Here at Analog Game Studies, we celebrate the fact that a leading periodical of our field now embraces our founding position stated 4 years ago: that (1) non-digital, “analog” games are, in fact, intertwined with the digital and (2) the therefore nonsensical label “digital” or “computer” when referring to “games” serves as a gatekeeping mechanism against designers (and scholars) without extensive backgrounds in computer programming or 3D modeling to the intellectual, historical, and political detriment of the field of game studies. Most notably, we argued:

“Because the barriers of entry to design do not require the technical expertise demanded by the lines of codes which bring computer games to life, analog games hold the potential to allow a new and different set of voices into design processes, voices which might resist the pathological displays of racism, sexism, homophobia, and violence native to the video game industry. … Because the impetus is on invention as opposed to industry, analog games epitomize the potentials of a design ethic which does not pander to over-generalized market demographics.”

Yet our ongoing conversation intersects with a broader context, for Aarseth’s statement raises larger issues related to the recognition of the non-digital in higher education. Most notably: what shall we do with a non-digital-friendly field of game studies as it encounters the technocratic apparatus and institutions of a digital-obsessed field of higher education in the 21st Century? How might Aarseth’s reconciliatory rhetoric be best mobilized to convince funding and job search committees, boards of trustees and administrators, parents and students that the future somehow involves non-digital awareness and expertise? In what departments and under what mandates should the radically interdisciplinary field of game studies exist, and what barriers to entry does the present “digital” distinction currently erect? Moreover, and perhaps more awkwardly: How bound together are technology, academia, and (racialized) capitalism in their commitment to computer and video games? Scholars addressing such questions seek the future of the field beyond 2018, rather than its seeming “future” circa 2001.

Analog game designers and scholars struggle to maintain legitimacy in our present academic environment, and examples abound. UK-based Intelligent Games and Game Intelligence (IGGI) recently advertised 12 fully-funded PhD studentships, about which virtual-worlds researcher Richard Bartle added: “Full-on, don’t-ask-me-to-program Games Studies won’t make the cut, but other areas might; procedural content generation, for example, could include narrative content.” “Don’t-ask-me-to-program Games Studies” is not only a cipher for knowledge workers in the humanities, social sciences, and media studies, but also for those designers who make games for the human platform rather than the computer. An upcoming “Games Against the Machine: Diversifying the Resistance” workshop initiated for the 2018 DiGRA conference expresses an interest in gender and sexuality in games without mentioning non-digital examples such as the #Feminism collection or Fog of Love. German academic listservs regularly announce new work on the “Computerspiel,” ignoring the incredible design advances in board games made primarily by German creators in the last three decades. A colleague assembles a game team for a local serious game project and, after being offered the expertise of on-campus game design students, writes to me requesting to be put in touch with only those “in COMPUTER SCIENCE.” Another colleague in a meeting dismisses the expertise of a woman analog game designer with loaded questions: “Who is this person? Do they have real experience in programming? In game design? Have they worked in the industry?” The unfortunate institutional and social bias of Aarseth’s unintentional “computer game research” monolith comes into sharp focus: Programming skill is equated with game design skill, “narrative content” is considered an afterthought, having been employed in the notoriously exploitative video game industry is a prerequisite, and the diversity of games and game authors is unimportant. It should give one reason to pause, the sheer irony that –– in the ideological universe of some –– digital game reality is more “real” than our own physically embodied cognitive reality. Something appears amiss about this, and Aarseth has come to recognize it.

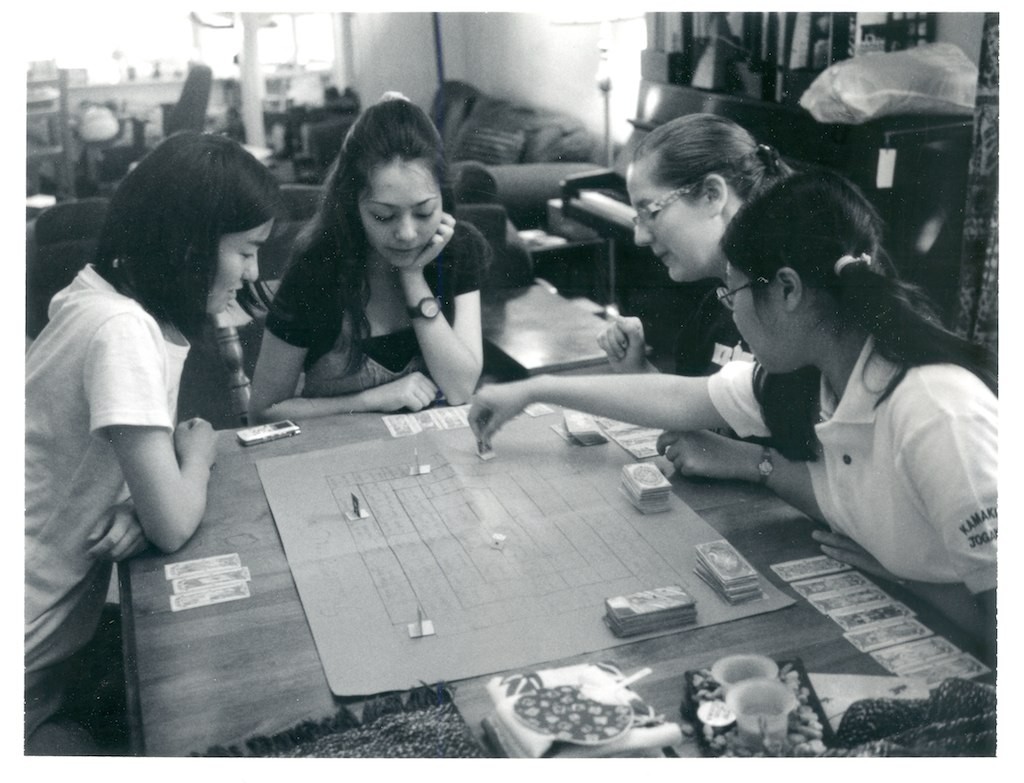

To echo Aarseth’s present position: analog games have proven themselves highly relevant as a social and economic force over the past decade. Who could have predicted what David Sax calls “the revenge of the analog?” Sax chronicles a recent shift as of 2012-13 away from the “digital utopia” promised by so many global businesses and institutions: consumers returning to physical retail stores, buying vinyl records that make music less convenient to play, writing notes in Moleskine notebooks rather than on one’s tablet computer, and so forth. He notably devotes a whole chapter of his analysis to the analog board game renaissance of the past decade. Digital tools and networks –– Photoshop, Google docs, Kickstarter, Board Game Geek –– have enabled a wave of innovation in form and content of board, card, dice, and role-playing games. But the physical, often-paper-and-plastic game materials coupled with co-present physical players are now considered a luxury to be enjoyed. “Analog gaming happens on multiple cognitive levels, which leads to a richer experience …” Sax writes. “With tabletop games, you are basically playing two games: the one on the table and the one around the table. With video games, you’re just pressing buttons.”

Ian Bellomy has noted that “technology is not essential for computation” and that, indeed “people can perform algorithms. People can read and enact algorithmic instructions. Analog game design is contingent on human algorithm enactment capabilities.” Behavioral neuroscience and psychology see new horizons in research on social emotions and the body. The discipline of film studies is now nearly two decades into its own somatic turn, initiated by pieces by Vivian Sobchack and Anne Rutherford, and video game studies appears positioned to follow suit. Sax’s journalism pinpoints not only a paradigm shift in business, but in academic theory on the topic as well.

The numbers and growth of the analog games industry over the past decade astound most commentators. Exploding Kittens (2015), for example, is a card game designed by two former Microsoft XBox designers Elan Lee and Shane Small with art by Matthew Inman of the webcomic The Oatmeal that is, for lack of a more elegant description, a glorified re-skinning of the party game “hot potato.” Yet the game earned the distinction of “Most-Backed Project of All Time” on Kickstarter in February 2015, with 219,382 individuals pledging $8.78 million to the cause. Because board, card, and role-playing games have low barriers to entry and well-defined overhead and risks, they best utilize the affordances of crowdfunding over other types of games. Analog game design conference Metatopia began in 2011 with 164 scheduled events; in 2017, it had 893 and quadruple the number of designer participants. Video-game convention franchise PAX now offers a “PAX Unplugged” event in Philadelphia specifically for tabletop games. At last year’s Foundations of Digital Games conference, Emily Care Boss and Lizzie Stark ran the now-canonical Nordic larp by Nina Runa Essendrop and Simon Steen Hansen White Death, “a poetic non-verbal larp that emphasizes physical expression” and involves 15 participants contorting themselves under a spotlight for hours on end. The financial, cultural, and material power of non-digital games shows few signs of abating at present.

The business footprint of non-digital games, however, should not be the final word as to their relevance. Scholars should remain wary of neoliberal benchmarks such as the profitability, economic impact, virality, and trendiness of specific topics. Indeed, the best work in many interdisciplinary fields scrapes away at the edges of the margins, seeking undiscovered truths where few have yet dared to look. Such work in the non-digital games realm manifests in the decisively unsexy labor of poring through old fanzines in archives, writing program scripts to comb scanned data of board game rules, or running a game dozens of times with different groups and sorting post-game questionnaire responses. One could describe the work of digital-only game scholars in similar unsexy terms: writing a grant proposal, debugging the programming script for a health-diagnosis game, scrolling through the Excel files of now-defunct loot tables, and so forth. Yet in the institutionalization of game studies since 2001, only the latter activities seem to earn the mantle of “proper” or “serious” game studies. Computer programming experience combined with a primary focus on digital games remains the ticket to employment in the game studies field, often seeking predominantly straight white cis male scholars under the Silicon Valley-created shroud of “merit.” The message is clear: finance capital demands an investment in the digital, whereas a more modest intellectual commitment to the digital would befit our field.

Preparing game designers as programmers for the “industry” should not be the fundamental goal of game design and game studies programs. Casey O’Donnell’s research demonstrates that both the AAA and indie video game studios premise their entire economic model on a fresh supply of young, enthusiastic programmers yearning to work in game design. This schema has had untold personal, societal, and aesthetic consequences, not the least of which are professional burnout and conformist game design. Robert Yang writes about this year’s Game Developers Conference (GDC) as a “post-indiepocalyptic” wasteland:

“Everything everywhere is kind of terrible for everyone. So many people are making so little money that it’s hard to distinguish their precarity from another precarity. … Throughout GDC I heard so many stories that made me realize working conditions are worse than I imagined, and there’s a shocking sense of resignation when I spoke to one AAA dev who predicted they were going to burnout with their next 100 hour workweek [sic] … like it was just htis inevitable natural disaster that was definitely going to happen… As someone who trains students in game development, I guess I’m extremely concerned about throwing my students into this giant machine that will mercilessly devour them!”

If non-digital designers appear naïve for calling themselves “industry professionals” after earning $300 for work on a Kickstarter project, digital designers appear outright dupes for heeding the siren song of writing code for an employer who will then dispassionately discard them after using up their youth. If crowdfunding of indie titles is even in the equation, board games continue to beat video games as viable means of employing design professionals to create deliverable product. Games and the study of their design should be pursued for intellectual, emotional, and societal goals, as the financial promise of the field withers on the vine.

In 2018, the world now lives in the shadow of Apple, Microsoft, Google, Facebook, and Amazon — a configuration of tech companies that monopolize user data, market share, and the overall outer digital frontiers. Placing any trust in these companies raises serious ethical concerns. Aarseth recognizes this to some degree, and at bare minimum understands “play” and “games” to be terms inclusive beyond the reach of these digital monopolies. Such an approach is insightful: the analog world once existed without the digital one, prompting the thought that one ought to be intellectually prepared for a world after the digital. Film archivist Paolo Cherchi Usai has noted that most of the moving images ever produced have now been destroyed, and we can expect for this destruction of the history of the moving image to accelerate as humans rely on digital devices under the control of corporate entities. We now have firsthand experience of the fragility of digital artifacts, from lost digital sound recordings to the data corruption and corrosion of older personal computer platforms not even a decade old. Although our engagement with the digital world is now ubiquitous, this very ubiquity now reveals the terrible environmental, security and epistemological effects of the current climate. In order for anything to change, one must imagine alternatives outside the present system. Moreover, traditional research on non-digital topics continues slowly along and produces on occasion extraordinary findings. Our scholarly gaze must be clear with respect to the stakes of our work and the blindspots encouraged by reigning ideologies of our present moment.

In the end, we applaud Aarseth for taking notice of the quiet analog game renaissance unfolding amidst uncertain times for digital, following Adrienne Shaw, Annika Waern, Frans Mäyrä, Jesper Juul, Drew Davidson and other major voices in the field who saw the value of our project early on. Nevertheless, the hard work only begins now: to staff game design programs with tenure-track faculty who have years of experience in non-digital design; to pivot institutional glorification of the digital millennium toward a more nuanced perspective that includes contributions of the non-digital; to examine and follow movements within analog game design theory and their epistemologies regarding actual play. The field must push back against backward notions that design begins with programming and 3D modeling, or that MMOs or massive open-world CRPGs matter more than tabletop RPGs and larps, or that “play” can only happen once massive hardware investments are made, as we currently see with the trend toward Virtual Reality (VR). Games and play exist within our capitalist, techno-fetishistic society, but our field does not have to uncritically support the latter when analyzing the former. Nothing is inevitable in game design or game studies, and that very contingency constitutes a position of strength. Let us use the non-digital to interrogate and contextualize the digital; the analog to keep the computer and its users humble. And let us take this philosophical position into larger struggles over what is taught in courses, who teaches them, and what knowledge overall is valued as we enter into a future only dimly lit by our smartphone and tablet screens.

—

Featured Image “Black Death” by Philip Cronjue @Flickr CC BY-NC.

—

Evan Torner, PhD (University of Massachusetts Amherst), is Co-Editor and Co-Founder of Analog Game Studies, and Assistant Professor of German Studies at the University of Cincinnati. He currently serves as Undergraduate Director in German Studies and Director of the UC Game Lab. His fields of expertise include East German genre cinema, German science fiction, critical race theory, role-playing game studies, and Nordic larp. Torner has contributed to the field of game studies by way of his co-edited volume (with William J. White) entitled Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Role-Playing and Participatory Media (McFarland, 2012) and numerous published articles on live-action, tabletop, and computer role-playing games. He co-founded the Golden Cobra game contest in 2014, and has served on the steering committee of the Living Games Conference.