Can We Read A Tabletop RPG As A Text About Nature?

In Video Games As Environmental Texts, Alenda Chang suggests a framework for “reading” video games as texts which teach and reveal our beliefs about nature.1 Chang argues that “almost by definition, all computer and console games are environments” – that is, video games are only playable because they simulate environments for the player to interact with.2 She draws on a reading of Adventure, an early dungeon-crawl style game in which a player uses text-based commands to explore a fantastical cave in order to argue that even the most low-fi video games create immersive “virtual realities” and represent fictional “natural” worlds.

However, Chang also notes that even when video games use rich visuals to immersively depict natural environments, many games’ mechanics depict nature superficially, and as secondary to human actions: “game designers [tend to treat] game environments as mere scenery…rather than attempting to plumb their biogeographical complexity.”3 Furthermore, video games often fall into a limited set of extractivist tropes, rewarding players for exploiting natural resources, and eliding the ecological consequences of these actions. In the past ten years, Chang’s paper and following works4 have kicked off a flourishing of ecocritical readings of video games and environmentally motivated video game design, asking what other stories about nature video games could be used to tell.

Despite their often-cited parallels with video games, there has been relatively little scholarly work on the topic of Tabletop Role-playing Games as texts about nature. The lineage of Tabletop Role playing Games (henceforth Tabletop RPGs or TTRPGs) is deeply intertwined with that of video games. In fact, the game designers who created some of the earliest text-based-adventure games, like Adventure in the 1970s and 80s were heavily influenced by early tabletop RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons.5 Both early TTRPGs and early video games shared ecological tropes of players crawling through “twisty little passages” or “Multi-User Dungeons,” discovering monsters and magical artifacts along the way.6 Given this relationship, we might expect that much of the environmental study of video games is also applicable to their close cousin, TTRPGs.

While scholarly analysis of TTRPGs often focuses on player’s experiences of role playing as human-like agents, scholars of TTRPGs recognize that role-playing games simulate “worlds” or “places”7 – or, alternately, though TTRPG scholars rarely use this language, “nature” or “environments.” Tabletop RPGs may not be “virtual” worlds in the sense of a highly-realistic, highly visual, high-polygon representation of the natural world.8 Nature in a tabletop RPG is not created through visual computer graphics, but through verbal descriptions of the world, and occasionally supplemented by rulebook illustrations, reference pictures, or maps.9 However, tabletop RPGs environments are “virtual” in Janet Murray10 or Marie-Laure Ryan’s11 broad use of “narrative as virtual reality” – they create shared imagined environments which players collectively inhabit, interact with, and manipulate objects within. As Chang12 reasons in Video Games As Environmental Texts:

“Edward Castronova suggests that immersion does not spring from verisimilitude but rather from “selective fidelity” to chosen particulars…realism is never purely the domain of the visual and that immersion requires little more than the “magic circle” provided by games or game-like scenarios.”

Therefore, while TTRPGs are not necessarily visual, the environments they create may feel just as immersive and real to players as video game worlds do – not too different from a low-graphics video games like Adventure.

While Tabletop RPGs and video games both simulate environments, a major difference, which must inform our environmental readings of TTRPGs, is that whereas a video game uses a computer to simulate the environment, TTRPGs use human players as their game engines.13 Though a game designer might encode some details in the game’s rulebook, the same way a video game designer might code them into the mechanics of a simulation,14 the players of the TTRPG themselves, not a computer, are the machine that runs that code – “The power to define the game world is allocated to participants of the game,” Markus Montola writes.15 A TTRPG’s rules are subjectively enforced by the human players, rather than rigidly enforced by a nonhuman computer system – “subjective” both in the sense that players are the subjects who “define the game world through personified character constructs,” and in the sense that rules may be enforced flexibly and selectively, in line with player’s own beliefs. Aspects of the setting of a TTRPG cannot exist without human awareness of them, since is only through the players themselves describing these parts of the environment that they come into being – every rock, river, or tree has to be intentionally placed. Thus, when reading TTRPGs as environmental texts, our analysis should be shaped by an awareness of greater player subjectivity in the medium – while a rulebook may make one statement about the environment, it is always possible that the storyworlds players actually construct will make another. And furthermore, players may have different empathetic or emotional reactions to interacting with an environment simulated by other players, or interacting as a part of an environmental simulation, than they might have interacting with an environment simulated by a computer.

What does it look like to read a TTRPG as an ecological text? In the next section, I attempt an ecocritical reading of the 5th edition of Dungeons & Dragons (2014), paralleling Chang’s16 critiques of the extractivist tropes common to many Triple-A video games. I then go on to detail a variety of techniques that designers might employ for constructing more environmentally conscious TTRPGs, and catalog several moves towards “green” TTRPGs that independent game designers are already making.

An Ecological Survey of Dungeons & Dragons

Mass-market tabletop RPGs, similar to mainstream video games, often depict players in an antagonistic relationship with an environment which they must conquer and mine for resources in order to advance in the game. Dungeons & Dragons, an RPG in which players level-up by fighting monsters and “looting” their treasure, is a classic and influential example of these tropes in TTRPGs. In this section, I inquire into what it means to simulate a world mostly composed of “Dungeons” (hazardous environments to explore) and “Dragons” (dangerous beasts to be conquered).

I choose to focus on Dungeons & Dragons (also known as D&D) because it is currently the most widely played TTRPG, and because it has historically played an important role in the development of North American role-playing games. Whether as satanic panic17 or cameos in Freaks and Geeks, D&D’s central role in American popular culture is unrivaled by any other TTRPG – if an American only knows of one TTRPG, chances are, it’s Dungeons & Dragons. D&D has been an influential force in game design since the 1970s and, with the help of RPG podcasts like The Adventure Zone or Critical Role, the game’s 5th edition remains popular among Millennial and Gen-Z audiences.18 In the following analysis, I draw on a close reading of the three core rulebooks of Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition – The Player’s Handbook (PH),19 The Dungeon Master’s Guide (DMG),20 and The Monster Manual (MM).21 While, as previously discussed, these rulebooks do not fully dictate how players interact with the game, these texts nonetheless constitute the designer’s official stances on nature, and make up an important part of how players are taught to think about the environment in their play.

As in many RPGs, narrative agency over the gameworld in Dungeons & Dragons is split between “Player Characters” (or PCs) and a “Dungeon Master” (or DM). Following the formula laid out by Montola in his 2008 comparative analysis of mainstream Tabletop RPGs, PCs in D&D take actions in the world through anthropomorphic avatars, and whatever “decisive defining power that is not restricted by character constructs is… given to people participating in game master roles.”22. This means, among other things, that the Dungeon Master takes on the responsibility of representing the natural world. The Introduction to the Player’s Handbook describes the basic flow of play in D&D like so: “the Dungeon Master is the authority on the campaign and its setting…The DM describes the environment…[then] the players describe what they want to do.”23 The Dungeon Master’s Guide further expands on the DM’s role: “it’s good to be the Dungeon Master! Not only do you get to tell fantastic stories about heroes, villains, monsters, and magic, but you also get to create the world in which those stories live.”24 In addition to representing the natural surroundings of the campaign such as the landscape and the weather conditions, “the DM plays the roles of monsters and supporting characters, breathing life into them.”25

While the language of the rulebooks underscore the Dungeon Master’s freedom of choice, the D&D rulebooks also guide and constrain the DM’s choices. The D&D rulebooks prescribe environments in two ways: flavor text and images, which players are supposed to take as inspiration, and mechanics, which governs how the environment interacts with the rules of the game. Dungeon Masters are nudged towards depicting certain sorts of environments by the pictures and descriptions in the rulebooks. The D&D rulebooks provide example descriptions of environments for DMs to draw on, and a basic cosmology of the D&D universe. Optional supplemental rulebooks such as the Forgotten Realms, Eberron, or Dark Sun “campaign settings” depict specific details of environments – for instance, Dark Sun provides special rules sets for representing a desert or jungle biome. Pre-written D&D adventures may further define environments, down to maps of specific settings. And then, Dungeon Masters are also constrained in what environments they can depict by what mechanics the rulebooks provide – what sorts of terrain have what mechanical effects, which stats are assigned to which creatures. Nonetheless, the Dungeon Master has the ultimate last word in representing the game environment to the players. They get to decide what suggestions to include or exclude, and what rules to enforce when.

While it is easy to confuse D&D’s Dungeon Master with the role of a video game player in a “god game” like The Sims or Rollercoaster Tycoon,26 the D&D rulebooks suggest that the DM’s enjoyment of the game should come not from the thrill of their absolute mastery over the setting, but from the satisfaction of creating an environment for other players to enjoy. While players of video games such as The Sims or Rollercoaster Tycoon might delight in the godlike power to arbitrarily dictate the lives of the hapless humans that inhabit them like ants in an ant farm, in D&D, it is generally considered in poor taste for DMs to create environments that are fun to them, but are not fun for the players. For instance, the classic D&D joke about the DM announcing “rocks fall, everyone dies” is funny because the DM is not supposed to play this way. It would be considered “spoilsport” behavior, against the “invisible rules”27 of D&D for the DM to delight in using the environment for their own enjoyment at the expense of the player characters – whereas it is much more acceptable for players to delight in using their characters as avatars to gleefully destroy aspects of the environment the DM creates. The other side of the coin being the long running D&D joke about players always killing plot central NPCs and derailing the DMs plans, which is funny precisely for the opposite reason as the “rocks fall” joke – that players do play this way. While D&D players often do become emotionally attached to the characters they play, it is considered more unusual for DMs to feel significant “bleed” from playing “as” the environment. The rulebook, and social norms around the game specify that the DM’s role is to craft a world for players to interact with, not to try and experience what it is like to role-play as a monster or a mountain. Montola’s 28 phrasing of the GM and player roles, which define the GM’s territory as anything “not restricted by character constructs” is telling – rather than defining the DM’s territory, and thus, the environment, positively, D&D defines the environment as a negative space. Like the scrolling backgrounds of Super Mario, nature in D&D is supposed to frame the character’s story like a theatrical set, to step back and let them take the spotlight. The D&D rulebooks encourage DMs to create environments which exist primarily for the other players’ pleasure.

What presentation of nature do the designers of Dungeons & Dragons expect players to delight in? Though D&D does not explicitly depict homesteaders, covered wagons, or cowboys, the game’s rulebooks often frame the relationship between players and the environment in a “frontier” narrative of exploration and conquest. The DMG states as a “core assumption” of the D&D world that “much of the world is untamed” – a phrasing that implies both a romanticization of an “untamed” wilderness and a manifest destiny calling the players to “tame” it.29 In Dungeons & Dragons, players play “adventurers” who venture into a natural landscape, full of fearsome monsters and abundant natural resources – the Dungeons & Dragons rulebook again and again stresses “exploration” as one of the main selling-points of the game. Like tourists on a fantastical safari, Dungeons & Dragons characters are mostly meant to “explore” the diverse and exotic species that inhabit the fantasy world by killing them. As in Nardi’s critique of fantasy video games like World of Warcraft, D&D promises an escapist narrative in which people from a modern, industrial society can travel to a virtual, de-technologized, natural landscape, and test their mettle against the “untamed” environment and its creatures, earning trophies and points for exerting mastery over them.30

Most of the mechanics that do heavy lifting in defining the world of D&D are primarily useful for putting players in direct conflict with nature. Players are encouraged to fight natural creatures they encounter because they gain levels and treasure from defeating these creatures. And nature, playing its part, is in turn hostile to players. “The wilderness can be just as dangerous as any dungeon,” warns the Monster Manual. 31 In D&D, there is actually no classification for a non-human being, other than “monster” – the stats for all creatures are indiscriminately listed in the Monster Manual, which describes itself on the cover as “a menagerie of deadly monsters.” “Harmless” natural creatures like toads and cats appear in an appendix tacked on at the end of the Monster Manual – the main attraction of the rulebook is hostile or “evil” creatures designed for players to fight. And even benign creatures like housecats and dolphins are defined in the Monster Manual by a “challenge rating” – a level indicating how hard a creature would be to fight, and how many experience points a player would gain for killing it. The same implicit antagonism is represented in D&D’s depiction of the inanimate natural world too. Dungeon Master’s Guide rarely provides rules for representing the positive effects of a beautiful landscape or clean source of water, but it does provide rules representing the negative effects of extreme weather, toxic mold, or impassable terrain.

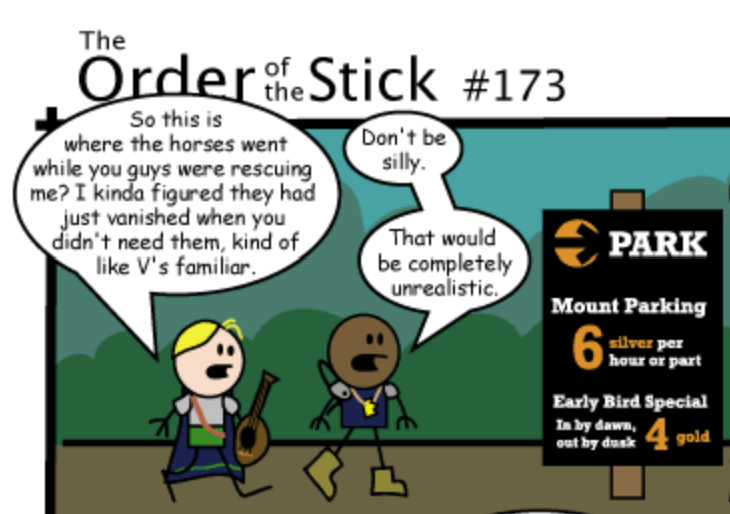

The rulebooks of Dungeons & Dragons consistently encourage players to think of the creatures that inhabit their fantasy world as a natural resource for exploitation. Mechanics representing animals appear in three places in the Dungeons & Dragons core rulebooks: in the items section (as property), in the player class abilities section (as special abilities related to pets, familiars, or animal companions), and in the Monster Manual (as beasts). In each case, creatures are defined through their usefulness to humans: as equipment that can perform tasks, as companions who can provide stat bonuses, and as monsters that can be killed for treasure and experience points. D&D players often forget about or intentionally choose not to keep track of the presence of their animal companions or pack animals, when it’s not convenient to the plot (Figure 1). Even in cases where D&D seems to nod towards a more symbiotic relationship between players and nature – for instance, the Druid class, who are are expected to act as magical stewards of nature – the mechanics still primarily define animals through their utility to human-like agents. Spells with names like “animal friendship” or “commune with nature” have mechanical effects only stated in terms of what stat bonuses they can convey to the druid, how they can coerce animals to work for the caster…rarely in terms of what the caster can do for the environment.

Nature in Dungeons & Dragons is meant to shape itself around human narratives. To use Nicholas Mizer’s words, D&D is often prioritizes “bending [nature] to meet [player’s] goals” rather than “cultivating the concreteness of the natural world.”32 The DM’s job defined in the Dungeon Master’s Guide is to “plac[e] monsters, traps, and treasures for the player characters…improvis[e] when the adventurers do something or go somewhere unexpected…[and] create a campaign world that revolves around their actions and decisions.”33 That is to say, nature should literally re-form itself depending on what players want to do and where they want to go. Even ecology should be thrown out the window in the name of player enjoyment: “regardless of which environment a monster traditionally calls home, you can place it wherever you want….it’s fun to surprise players.”34 When ecological realism is to be maintained, it is to make the world comprehensible to players, rather than for the sake of realism itself: “an inhabited dungeon has its own ecosystem…if the dungeon doesn’t have some internal logic to it, players will find it difficult to make reasonable decisions within that environment.”35 Even physical space in D&D is literally defined in terms of how anthropic agents can interact with it – the maps in D&D rulebooks and pre-made adventures, for instance, are divided into squares based on how far a player can travel in one round of play, and objects like rock walls or doors are assigned “hit points” based on how much “damage” a player would need to do to break them.

However, despite the D&D environment’s fluidity and responsiveness to human action, the D&D rulebooks provide very few rules for modeling player’s potentially deleterious effects on the environments they may trample through. Despite its simulationist36 rule set for combat, D&D has no rules describing pollution, deforestation, environmental collapse, or species extinction. While The DMG does provide some guidelines for depicting natural disasters, the game provides no mechanics for modeling long-term climate collapse. No matter how many dragons players slay, there will always be more.

I don’t mean to say here that D&D in particular is an atypically anti environmentalist RPG, but rather, to illuminate the assumptions about the relationship between humans and the environment which are embedded in D&D, and the many other mass-market TTRPGs which share similar mechanical foundations. I also don’t mean my analysis as a condemnation. As Chloe Germaine has argued, with regards to ecological horror RPGs, portraying the environment accurately needn’t be the main job of every escapist fantasy, and, under the right conditions, encountering a hostile environment in a game can be a valuable cathartic processing experience for denizens of the anthropocene.37 But I am more interested in what it says about our conceptions of nature as a society and as a game-playing community when most popular TTRPGs fit into one narrow and antagonistic set of tropes for representing nature, and games depicting any other sort of environmental counter-narrative are so scarce. In the next section, I explore a series of games which do take up those counter narratives, exploring how wide a range of modes of engaging with the environment TTRPGs are able to facilitate, once we move past the extractivist and anthropocentric assumptions which Chang (2011) has argued also burden mainstream video games.38

Imagining “Green” Tabletop RPGs

How can we create tabletop RPGs which promote more caring and ecologically-conscious understandings of the environment? My aim here is not a comprehensive set of instructions – I leave the task of actually imagining these games to designers more skilled than me. But in order to help us all get started on this endeavor, I briefly catalog here, using Chang and Parham’s taxonomy of “green” games, a few ways that game designers are already creating games, that “defamiliarize accustomed [anthropocentric] modes of control”. 39

Most of the existing academic work on “green RPGs” focuses on explicitly educational environmentalist RPGs.40 Mostly, these games are created by environmentalist organizations, to spread awareness about environmental issues or teach earth science. Some are designed to be played in classrooms by children, whereas others are intended to be train policymakers and crisis responders.41 These games are designed to educate, or sometimes to move players to actually take political action as a part of gameplay.42 These games are “green” in the sense that their content is green – they explicitly focus on the environment and espouse environmentalist attitudes. While these games play an important educational role, I also ask, what other, more aesthetic environmentalist interventions could Tabletop RPGs create? How could “green” attitudes be incorporated into more recreational gameplay?

A first step might be to think about games with more ecologically affective, but not explicitly environmentalist, narratives. Jenna Moran’s games Nobilis(1999)43 and Glitch (2020)44 present one compelling example. In Nobilis players take on the role of humans entrusted with stewarding a particular aspect of reality. Rather than sidelining the natural world, these games take place in what Moran calls an explicitly “animist” world, where player’s magical powers are intimately tied together with the setting. In Moran’s games, which she has said are influenced by Hayao Miyazaki’s contemplative, nonviolent, environmentalist films, players level up by coexisting with nature, rather than conquering it – for instance, in Glitch, players can gain experience points from contemplative moments like “[seeing] sight of quintessential natural beauty and majesty.” Without ditching the character-centered, high-action narrative structure of a classic tabletop RPG, Moran’s games are narratively structured to steer players towards representing a more amiable relationship with nature in the game world – these games may not come off as “environmentalist” to most players, but they nonetheless encode more environmental empathy into gameplay.

We could also consider TTRPGs which encourage players to consider the subjectivities of natural objects – as Chang might say, which “can give us an insight into what it means to be other-than human.”45 Worldbuilding games, like Avery Alder’s The Quiet Year (2013)46 or Caro Ascerion’s i’m sorry did you say street magic (2020)47 are one way to do this. Rather than pushing the environment to the background and focusing on human actors, these games make the environment the main focus of play, asking all players, and not just the Game Master, to take up responsibility for natural forces, terrain, or geography. Unlike D&D, where representing nature is seen as a non-player role, these games call on all players to to develop an empathetic relationships with the game’s setting and all of its residents.

We can think about how the TTRPG medium could be used to create “tactical” or “dissonant” games48 – that is, thought-experiment games which might startle players into viewing their relationship with the environment in a new way. Caitlynn Belle and Ben Lehman’s The Tragedy of GJ 237b (2017), which tells the story of human explorers landing on a planet inhabited by a microscopic civilization invisible to them, is on example. This game de-centers human players – the human players are meant to leave character sheets, pens, pencils, and dice, in an empty room, behind a shut door. “The game, being played in the room,” the rulebook tells us, “is about the history, societies and cultures of GJ 237b. It is not something that you can play, or even understand.”49 The only action that human players can take is to open the door – when they do, “they are the human explorers that have arrived on GJ 237b [and] the game immediately ends,” as the microbe civilization is accidentally destroyed by humanity’s intrusion. Though some might even question if The Tragedy of GJ 237b can properly be called a TTRPG, just reading the game’s rulebook can unsettle readers’ accustomed anthropocentric notions, and remind them of human exploration’s dangerous potential for even accidental ecological destruction.

Finally, it is crucial to not discount the possibly for players, rather than game designers, to create “green” modes of play. Like the players described by Bo Ruberg who “queer” even overtly homophobic games by using them as tools to tell queer stories,50 players can construct ecologically conscious gameplay, even using colonialist or extractivist rulebooks. D&D already has a strong history of players house-ruling out the game’s racial ideology,51 penciling in queer characters where no positive representation existed,52 “house ruling” out mechanics that are deemed too complex, or writing their own “homebrew” rules supplements.53 In my time as a D&D player and DM, I have encountered many players who, despite what the game’s rulebooks say, would rather befriend monsters than slaughter them, write plots about ecological conservation, or take time to narrate stopping to smell the flowers. Of course, players may also invent less-ecologically conscious models of play – such as the infamous “munchkin” players who indiscriminately kill NPCs, trampling over the gameworld and the DM’s plans in order to maximally exploit the game environment and level up as quickly as possible. The point stands though, that while many RPG rulebooks bring colonialist or extractivist views to the table, these rulebooks are not the be-all and end-all of how nature is represented in actual play – players, as well as game designers, can imagine new ways of relating to the environment.

I don’t intend this paper to be a comprehensive list of existing green tabletop RPGs, or methods of play. But I do hope that future scholars and game designers alike will take note that the frameworks which Chang and Parham54 provide for thinking about “green games” or “games as environmental texts” can, with a bit of modification, be extended to the analysis and criticism of TTRPGs. Let us go on thinking: What narratives about nature can we read in TTRPGs? What possibilities for understanding nature are opened up by a medium where every detail of nature is represented through collaborative human description and re-enactment? And how can we use the power of co-created oral virtual realities in tabletop gaming to cultivate greater empathy for and understanding of the environment?

—

Featured Image is Forest Floor Fantasy Hat by Hauke Musicaloris @ Flicker CC BY 2.0

—

Mehitabel Glenhaber is a comic artist, RPG designer, and independent scholar based in Somerville, Massachusetts. They are the author and artist of the environmentalist comic strip Greenhouse Affect, and upcoming comics collection Carbon Fingerprints (from Stelliform Press). Their work as a Tabletop RPG and LARP writer can be found at @hittiebelle on itch.io.