I listened to my partner read the rules as I pressed my fingers along the cardboard perforations, freeing each token one-by-one. The objective in this game is to win the most victory points—a task primarily achieved through strategic race selection and territorial expansion. “Easy enough,” I thought, mentally noting its similarity to other games I’d played.

Weighing my choices, I asked, “What happens to the Lost Tribes if I move here?”

“I think it just goes back in the box,” my partner responded while thumbing through the rules.

“Really? That’s it? They don’t come back onto the map like race tokens do?” I pressed.

“Yeah,” he assured me, “It just costs more to take their territory, but as long as you have enough to cover the cost, they just go back into the box, and you get the land.”

Uncomfortable for reasons I couldn’t quite parse, I found my mind wandering to memories of childhood. “I’m not playing anymore!” I’d whine, practically begging to be taken seriously. That kind of outburst was usually the result of physical or mental discomfort like when horseplay pushed the boundaries of “fun” or when it had become painfully clear my brother was about to defeat me in another game. As an adult, I’ve come to recognize that such an exclamations are inappropriate, that there are ways you are expected to behave.

I quieted the impulse, but still felt it there, beneath the surface, threatening to boil over, begging to be taken seriously.

The tension between social and cultural expectations of behavior and what we do in the games we play is central to conversations in game studies. Cultural historian Johan Huizinga’s “magic circle”—the invisible boundary that divides play space from the rest of ordinary life—has been a core concept in these debates.1 As ludologist Jesper Juul explains, “playing a game not only means following or observing the rules of that game, but there are also special social conventions about how one can act towards other people when playing games.”2 Despite being broadly understood as a boundary, the magic circle is not impenetrable; it is socially negotiated among players. Juul argues that because it is co-constructed, the magic circle should be examined within its specific context rather than applied as a one-size-fits-all explanation of the absolute, unchanging barrier between the real world and the temporary game-world. Following this vein, in this article I will analyze my own experiences playing the board game Small World (2009) in order to explore how games can position players in networks of social difference. Using visual rhetorical analysis, textual analysis, and the lens of performance, I will specifically examine the role of the Lost Tribes tokens in Small World and their possible implications for players. In doing so, I show how games place players in precarious social positions by expecting players to perform in ways or to enact values that contradict their lived realities.

Player Positionality, Performance, and the Production of Fun

Many scholars have dedicated their work to studying games and play in effort to better explain and understand the place of games in our world. What makes games different and sets them apart from other social practices? In what ways are games similar to other forms of media, and other activities? As board game designer and historian Bruce Whitehill demonstrates in his analysis of The Mansion of Happiness (1843), American board games were once designed as tools intended to teach players (usually children) how to live in the world, and have only recently become reframed as mere leisure activities characterized by play and fun.3 That games have become closely aligned with cultural beliefs about frivolity, play, fun, and the non-serious is the impetus behind anthropologist Thomas Malaby’s essay, “Beyond Play: A New Approach to Games.” Malaby argues that many dominant narratives about games are the result of uncritically layering the study of play atop the study of games. The assumption that games and play must necessarily be joined sustains the belief that games are necessarily separate “from what matters, from where ‘real’ things happen.”4 Even the idea that games are “potential utopias promising new transformative possibilities for society”5 suggests they are somehow beyond everyday experiences. Rather, much like Juul’s call for examining instances of the magic circle within its context, Malaby suggests that we can create a more enriched body of study if we work toward understanding the various contexts that open up or limit possibilities for “cultural accomplishments” like fun.

Some game scholars do this kind of research (often indirectly) by examining how social difference is represented in and by game components, mechanics, and themes. Such critical conversations regarding board games, specifically, have been circulating at Analog Games Studies where Nancy Foasberg’s examination of Goa (2004) and Navegador (2010) illustrates how foundational economic mechanics in the games combined with selective historical engagement replicate “colonial fantasies;”6 Will Robinson discusses the ways games “contribute to Orientalism, shaping what the East is to the West through abstraction and the politics of erasure;”7 and Greg Loring-Albright advocates abandoning Catan’s (1995) “frontier myth” in favor of a critical modification that incorporates indigenous tribes rather than ignores their existence.8 Critical games scholarship, by critiquing the perpetuation of particular narratives (e.g., classist, racist, sexist, heteronormative, colonial, and capitalist) underscore how “fun” can depend upon player positionality. Furthermore, the study of how games (re)produce dominant narratives and Western ideologies raises important questions about the implications that these games have for players. Because tabletop games are often seen as leisurely, low-stakes activities (which are, therefore, relatively inconsequential), it is expected that individuals assume the roles and values assigned to players in a given game—even, and perhaps especially, when this means engaging in practices they would otherwise disagree with, and in some cases, condemn. It is this very expectation that makes the work of both Foasberg and Loring-Albright so important. Concern for the ways individuals navigate the complicated positions they are expected to occupy as a condition of agreeing to play the game (or to enter the magic circle) is integral to both Foasberg’s and Loring-Albright’s research.

Whereas much of the work outlined above centers on game components, mechanics, and themes to reveal the privileging of particular values, I analyze my own positionality in relationship to a specific game (Small World) to illustrate how one’s necessary compliance with such mechanics or themes can spoil, interrupt, or bar the very production of “fun” through gameplay. Additionally, my work centers on how games both open and close possibilities for the performance of—that is, the (re)construction of—identities, and demonstrates how games, by placing players in precarious positions of social performance, are spaces where meaning must be (re)negotiated, contested and (re)shaped. Here, performance is both the simple execution of tasks as expected (i.e., playing by the rules and with the objective of winning the game), and a theoretical frame for thinking about the (re)construction of social identities. Sociologist Erving Goffman’s understanding of performance as “all the activity of a given participant on a given occasion which serves to influence in any way any of the other participants,”9 speaks both to the social roles we play in our day-to-day lives, as well as the simple ways our actions in a game influence the actions of others (e.g., modifying strategies and moves based on the actions of others, or eliminating options for other players by removing pieces from the board). Even activity that is not regulated by the game itself, such as our body language, can influence how other players participate. More important to my argument, however, is the notion that identities are (re)constructed through performance, and that engagement in and with games—which do not preclude the lived realities of participants—often requires performances that (re)construct the self in relationship to the game. As philosopher Judith Butler has famously argued, identities are not fixed and stable. They do not exist before or outside of discourse and performance; identities are thus shifting and flexible, constituted by iterative performances.10 In this way, the repetition of non-neutral actions as part of gameplay, can be understood as a means of performing, or (re)constructing, identity.

The Lost Tribes of Small World

In this section, I examine the game Small World as one example of how player positionality (i.e., the extent to which players identify or align themselves with the game’s expectations) affects the game experience and how game actions open and close possibilities for the (re)construction of identities through performance. I have chosen Small World as my example because it is generally well-received and popular, and also because it relies on familiar and relatively accessible mechanics, which allows me to focus on analysis rather than explanation of the game. Although I briefly describe the game’s mechanics and theme and conduct a brief textual and visual analysis of its components, I do so to contextualize the focus of this section: positionality and performance in game play. By using performance as a lens for considering my own positionality, I demonstrate how—and argue that—players must sometimes perform in ways that complicate, contradict, and even undermine their own lived realities.

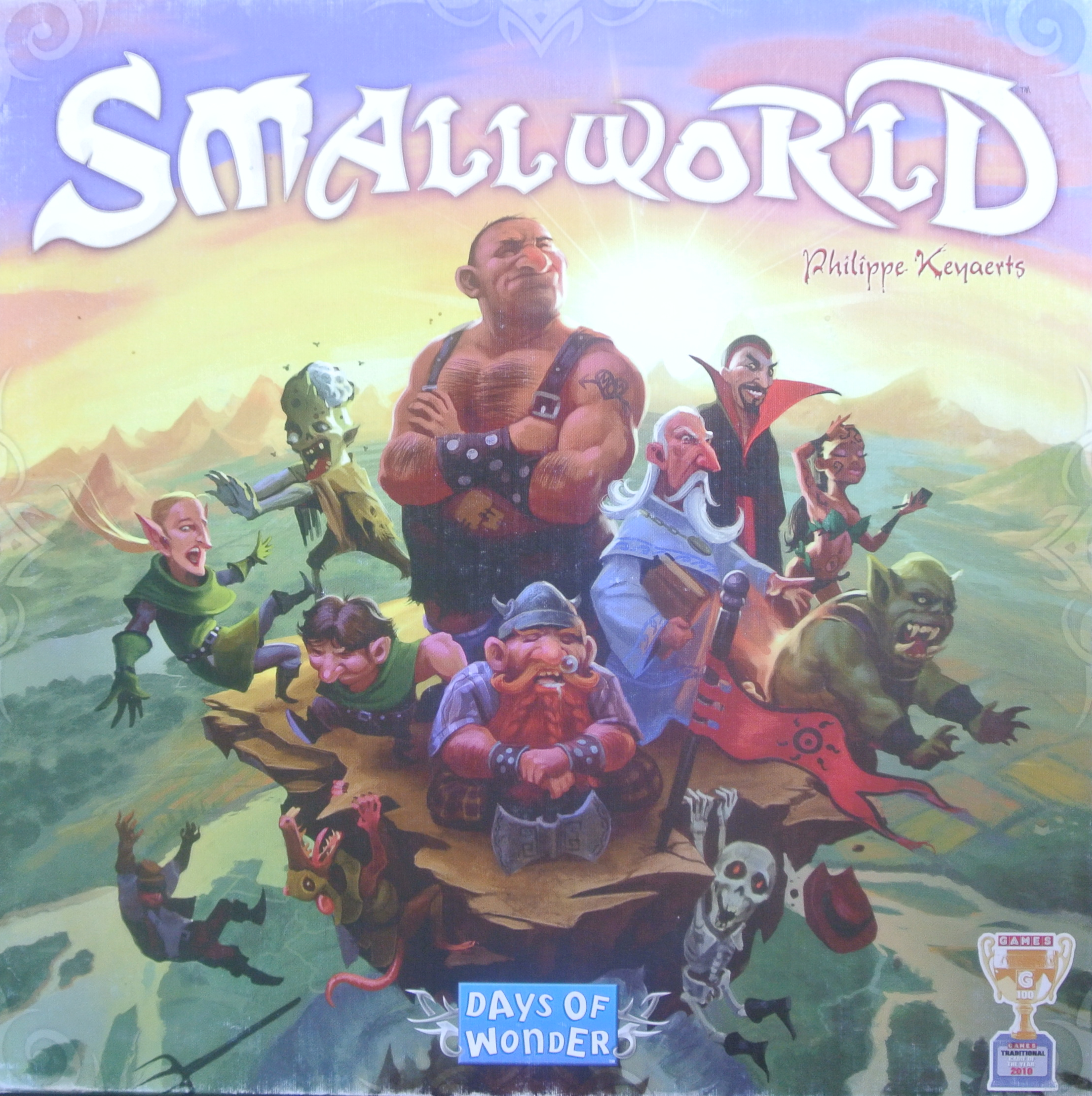

In 2009, Days of Wonder published Philippe Keyaerts’ Small World, the highly anticipated follow-up to Vinci (1999). Small World is an area control game like its predecessor, but what sets it apart is the combination of its positive reception among designers and players,11 its eye-catching and award-winning artwork,12 its adoption of a fantasy theme (departing from the more common settler-colonial or civilization themes), and its resistance to easy categorization among hobbyists. Although bearing many similarities to Eurogames, such as indirect conflict, Small World’s mechanics favor direct conflict in a manner typically associated with Ameritrash games, as evidenced by the language displayed on the box: “It’s a World of (S)laughter, After All!” Small World embraces and emphasizes a cut-throat battle of races, in which players “use their troops to occupy territory and conquer adjacent lands in order to push the other races off the face of the earth . . . players rush to expand their empires—often at the expense of weaker neighbors.”13 Such militarized language—“troops,” “occupy territory,” “conquer,” “expand their empires,” and “expense of weaker neighbors”—is juxtaposed with vibrant, colorful, cartoon-like designs that ultimately overshadow the darkness of the text. The appearance of fantasy races (Amazons, Dwarves, Elves, Ghouls, Giants, Halflings, Orcs, Ratmen, Skeletons, Sorcerors, Tritons, Trolls, and Wizards), along with the game’s artwork, lightens the overall tone of the game. Ultimately, the design signals to players that the game is not real, that the game is fantasy, and that by engaging with the game, one is pretending to be something they are not.

While the text and artwork of Small World is a rich area for further analysis, this article focuses on how the game’s rules—specifically concerning the Lost Tribes—positions its players in social relations that exist both in and outside of the game itself. As a Filipino-American, cisgender woman, I am socially, culturally, and economically positioned (and read) differently than many of the people with whom I often play games. Therefore, although we may be playing the same game and following the same rules, each of us experiences the gameplay in different ways. These experiences are particularly complicated for players whose realities are not represented and/or are contradicted by elements of the game.

In Small World, players begin their first turn by selecting from a randomized set of face-up race tokens. Using the race they have selected, they spend each turn strategically conquering territory on the board. Each region occupied by a player’s race at the end of their turn earns them a victory point. Play continues with their selected race until players use a turn to place the race into decline, at which point they remove most of those tokens from the board and use the following turn to choose a new race. The player with the most victory points at the end of the game wins. Prior to Small World, I had played a number of games in which territory expansion is the primary means of winning. So, this gave me little pause. Part of this process sometimes involved overcoming obstacles, such as lairs, mountains, encampments or other physical obstacles that would generally make taking the land more challenging. Still, this made sense to me. Of course it would take more people—and more loss—to conquer a region with unfamiliar terrain. The same is true of taking land from other races in the game. If Trolls want to take land from the Orcs, there will be a battle and some will be lost. However, one aspect of the game halted me: the Lost Tribes.

The game rules describe the Lost Tribes as “remnants of long-forgotten civilizations that have fallen into decline but still populate some regions at game start.”14 Their function is similar to lairs, fortresses, or mountains: to take a region occupied by the Lost Tribes, a player must pay an additional race token. Mechanically, this seems similar to taking land from an opponent, but the Lost Tribes are impacted differently. Despite its resemblance in size and shape, the Lost Tribes are not considered a race token. While race tokens can be redeployed, the Lost Tribes cannot. Instead, they are removed from the board and returned to the box, a point that can have a significant effect on individual player experiences. Furthermore, the artwork on the token offers relatively few details compared to race tokens: a white outline envelops a blend of reds, browns, and blacks to create shadowy profile known only as the Lost Tribes. Regardless of whether they are intended to be humans or humanoid creatures, they occupy a dehumanized position in relationship to game’s race tokens. Literally faceless, the Lost Tribes are thus represented more abstractly than race tokens, which are illustrated with richer, more detailed visuals including facial features. Even in name, their fate is predetermined. They are to be forgotten, to disappear from the world as their land is taken. Their only function is to be eliminated; they exist for eradication at the hands of others.

Not until I was confronted with the choice of taking their land was I confronted with my own positionality as a player of color. To play the game to win was to take their land, returning the token to the box, and earning victory points for doing so. Yet, I found myself choking on my conflict. I wanted to win, but I didn’t want to participate in this kind of narrative. The game-world began to collapse; the magic circle began to look a lot more like everyday life. With clarity, I saw the way my choice would symbolically constitute myself, and how, as sociologist Dennis Waskul argues, “neat distinctions between person, player, and persona become messy . . . erod[ing] into utterly permeable interlocking moments of experience.”15 Something stirring crawled inside me, pushing and pulling in different directions at once, and this thing, having been there for only a moment, turned these seemingly separate pieces of me into a viscous, malleable muck, making clear the muddiness of the self, the messiness of my positionality. In games, Waskul explains, players must take on “a marginal and hyphenated role that is situated in the liminal boundaries of more than one frame of reality.”16 I knew I was removing a token from a board, but I also knew that having to physically do this—replace the Lost Tribes with my own token and physically eliminate them from the game—felt like a socially symbolic gesture of approval. I felt I both was and wasn’t participating in the eradication of Lost Tribes. This was a moment of what critical cultural theorist José Esteban Muñoz calls disidentification:

To disidentify is to read oneself and one’s own life narrative in a moment, object, or subject that is not culturally coded to “connect” with the disidentifying subject. It is not to pick and choose what one takes out of an identification. It is not to willfully evacuate the politically dubious and shameful . . . It is an acceptance of the necessary interjection that has occurred in such situations.17

As a player of color, I recognize in this moment of tension that Small World was not designed for me, and yet, it also was. I live in a reality where most texts and activities I consume are not made for me, and yet, I consume them—voraciously, and with a pleasure of questionable authenticity. As a gamer with a particular appreciation of Eurogames, a gamer who enjoys winning, and often at games that require me to engage in activities I would never condone otherwise, I am, in many moments, the kind of person for whom Small World is created. Thus, while I am overtly critical of this game’s inclusion and treatment of the Lost Tribes, I also recognize that it is productive. It produced, in me, the need to vocalize my disapproval, to re-read the game through the eyes it was not meant for, to “to hold on to this object and invest it with new life,” by performing in this essay, the decoding of a “cultural field from the perspective of a minority subject who is disempowered in such a representational hierarchy.”18 While I cannot account for the experiences of other players, I hope that in seeing me publicly begin the work of theorizing my own experience as a tabletop game player and researcher will open up the space for others to consider the significance of moments when gameplay unfolds unpredictably, reaching beyond the magic circle, and into lived realities of everyday life.

Conclusion

As game scholar Mia Consalvo argues, an overly rigid concept of the magic circle erases the very real ways in which our lives and identities both touch and are touched by the game space.19 I suggest that we look to these moments of tension as productive moments of negotiation. The Lost Tribes in Small World should neither be overlooked as an unimportant element of fun, nor wholly condemned as overtly complicit with racist and imperialist ideologies. Rather, examples such as this serve as important nodes of tension that can lead to productive conversations.

As critical game studies show, and my work here illustrates, games often require that players negotiate multiple positions: some oppressive, others imperialistic, still others racist (though none are mutually exclusive). When navigating social terrain requires movement along paths that are not for us, our movement becomes one of reconciliation, fraught with the contradictions among sense of self, expectations, and performances. And when these moments of tension present themselves, when they are recognized and felt, they become moments of performance—opportunities that are never wholly good nor wholly bad, but that must instead be seen as presenting players with a chance to (re)negotiate meaning. These are productive moments, creating needs, feelings, and (re)actions among players, scholars, and designers. For instance, others who have struggled with this element of Small World have turned to modifying how the Lost Tribes function within the game, reaching for a critical modification not unlike that proposed by Loring-Albright.20

When I encountered the Lost Tribes in Small World, I was confronted by the simultaneous pleasure and displeasure of my disidentification with the player position constructed by the game’s language, artwork, and mechanics. This is evidenced in my own symbolical contribution to a narrative of erasure entrenched with values I would not typically call my own, feeling uneasy with this choice, and coming to the realization that perhaps they are my own and I am merely being called upon to recognize them. Both are true and neither is always the case. When the condition of playing the game by the rules necessitates performing or acting out what we recognize as a contradiction of who we believe we are, or who we want to be and want others to see us as, there is both possibility and limitation. They are not separate, but bound together, existing in uneasy tension that can lead to productive conversations and new ways of gaming.

–

Featured image used with permission of the author and reproduced for purposes of critique.

–

Antonnet Johnson is a PhD candidate in Rhetoric, Composition, and the Teaching of English at the University of Arizona (UA). Her research and teaching interests include game studies, rhetoric in popular culture, fan studies, play, and professional and technical writing. She is also Co-founder and Director of the UA Usability and Play Testing Lab, which specializes in research and testing on the design and usability of technological, instructional, and artistic prototypes.