“Try to play with people outside your usual circles and pay attention to when the game is pushing them to do things that are “in-genre” whether they knew about it beforehand or not.”

Indie role-playing game design, or the self-publication of RPGs by creators who retain rights to their own work, has become an integral part of the contemporary role-playing landscape. Games such as Breaking the Ice (2005), Fate (2003, 2013), and Dungeon World (2012) are now regular staples at conventions and around the dinner table. And whereas the indie board game community has gathered around sites such as BoardGameGeek and Board Game Jam, the indie RPG design community has congregated on platforms including Story Games, Gaming as Women, Google+, and the now-dormant Forge website.

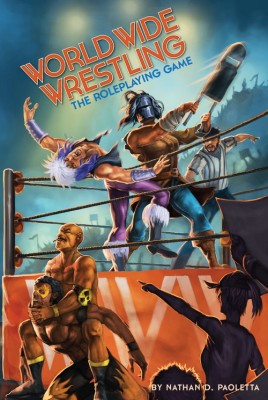

A self-proclaimed Forge alumnus and “game, graphics and objects designer and fabricator,” Nathan D. Paoletta has been resolutely pushing the boundaries of indie RPG design into barely charted territory for the last nine years. Hailing from New Mexico and currently based out of Chicago, Paoletta creates artisanal RPGs that, on an aesthetic level, are remarkably in tune with the feel of the original source material. His work stands out in an increasingly well-populated field of RPG designs, including his recent release World Wide Wrestling (2015).

Here I wanted to talk a little bit more about the different forms of fiction and design that inspire him, and how that affects RPG design. Given a post-Forge environment, I actually wish to preserve some of the jargon from that forum that still structures the conversation around RPG design, for which we have provided links, references and definitions.

Evan Torner: In recent years, tabletop RPGs have become increasingly diverse tools of expression, with sources of inspiration that reach beyond standard fantasy, horror and science-fiction tropes. Your games in particular draw on fairly unconventional subject material: Vietnam war narratives in carry (2006), Gothic horror novels in Annalise (2008), art nouveau in The Death of the Gilded Age (2014), to name a few. Tell us a little more about your sources of creative inspiration and that moment when you say: “This could be a role-playing game!”

Nathan D. Paoletta: Designing games is my medium, so I don’t think there’s a specific switch in my head for “this could be a role-playing game” as opposed to some other kind of artistic output I could be doing. That said, my sources of inspiration are pretty banal, and are often in service to constraints of some kind. I see a movie or read a book or something and have some thoughts about how that might turn into a game, and then sometimes it’s a sufficiently grabby idea and I try it out, or it ends up matching another project I’m working on better than what I already had in mind. For example, carry was originally a game design contest entry, with the constraints of something “historical,” and I wasn’t aware of any good Vietnam games. I actually literally flipped a coin between Vietnam and delving into the little I knew of Aztec history. The Death of the Gilded Age, on the other hand, was a theme that I then applied to a long-standing design idea I’d had that had never gelled. The final product was actually designed almost from a “graphics-out” as opposed to “mechanics-out” perspective.1

All of my games have a story like that behind them. I think there is this idea that when someone designs a game in a genre, it’s because they are in some way obsessed with or an expert in that genre, and in my case it’s almost the opposite. I feel like I become more expert in a genre by designing a game. Annalise is probably the only exception, in that I’ve always been fascinated by vampire stories and gothic horror, but I definitely read more during and after that process than I had before.

ET: Your latest game – World Wide Wrestling – manipulates the constraints of the pro wrestling world. The game’s subtitle is, interestingly enough: “The Professional Wrestling RPG of Narrative Action.” After having read it, I am under the impression that it is one of the most self-reflexive RPGs – that is, a role-playing about the act of role-playing – since Meguey Baker’s 1,001 Nights (2006, 2012). How is narrative treated in the RPG, and how does that correspond with narrative conventions of pro wrestling?

NDP: This is a bit of a long answer, but there’s a lot here to talk about! One key insight for me was that both pro wrestling and role-playing are “live” media: watching a wrestling match in a vacuum is like listening to a recording of someone else play. You can see what’s going on, but you don’t feel it unless you’re part of it. For pro wrestling, it’s the relationship between the performers, the audience and the backstage storyline decisions (the “booking”) that makes it its own art form. I try to reflect that in the game by keeping those three stakeholders distinct and mapping them to the role-playing group.

First, one of the key conceits in the game is the “Imaginary Viewing Audience,” the idea that the SIS2 is being performed in front of a fictional crowd, and that the feedback from that fictional crowd – governed by some of the games mechanics – has an impact on the ongoing narrative. Of course, the Imaginary Viewing Audience is in fact the group itself, at the table, playing the game. In the same way that a player is simultaneously themselves as an actual person and their performative role, the actual group itself is assigned a performative role as the audience to their own play.

Second, players play professional wrestlers as professionals, in that the player’s characters are the ones who take on fictional wrestling characters to perform in front of the Imaginary Viewing Audience, and those characters can change, be abandoned or evolve over time just as the player’s character gets new stats and mechanical choices and improves their ability to perform through extended play. You play a character playing a character, essentially.

Finally, the GM role (called the “Creative” in this game) is much like the one in 1,001 Nights in that it’s a largely fiat-based3 position that takes some classic GM duties that have historically opened the door into socially abusive or toxic behaviors and moves them front and center where they can be part of the game, and not hover over it unspoken. In particular, the Creative basically plans out each session in advance, down to who’s going to win what match. In a way, this is a classic railroad4 or “let’s play through my story” mode, but the game uses wrestling tropes in order to hand in-play power to the individual players to choose to go with, or try and change (“swerve”) what the Creative has planned during play itself. One of Creative’s primary duties is to take these swerves and “make it look like it was planned that way all along” to the Imaginary Viewing Audience, which is both an key aspect of pro wrestling (i.e., not letting the real changes break the audience’s suspension of disbelief), and also of improv-heavy GM and facilitation styles that are part of my personal play culture.

All of this meta-ness is (I hope) mostly embedded in the game itself. When you play it, you can just play, and if you want to pay attention to the meta factors you can, but – unlike, say, Paranoia (1984, 2009) or The Extraordinary Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1998) – the meta-ness of what you’re doing is key to the play experience.

ET: Indeed, your RPGs do well at accommodating multiple play agendas: I can play to win, play to lose, or play for some other reason, and the game still responds to my needs. In many ways, the designs respond to older debates about what the players apparently want from the fiction at the table and how that fiction is produced. How does adapting material from other media contribute to our theories about how role-playing works?

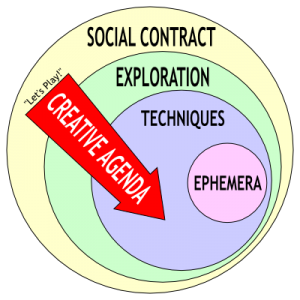

NDP: I subscribe to a pretty conservative version of the Big

NDP: I subscribe to a pretty conservative version of the Big

Model5 in terms of my theory background and how I think about games as I construct them. So, in that context, the inspiration I draw from another media tends to start with Color6 (and sometimes Setting), and I try to build systems that will reliably generate the Color that I’m aiming for. This may sound weird because many of my games (especially my older work, like carry and Annalise) have a dimension of emotional engagement, which tends to be cast as the opposite of “mere” Color. To me, though, color (in the colloquial sense) is the entry point into the narrative style or into the emotional engagement: when I play a game I usually need something very obvious around which to build my experience , either on the character level or something out there in the game world.

Again, in the pursuit of reliably generating Color, I usually end up

having to deconstruct the moving parts of the genre in which I’m working, or at least the ones that are important to me for the purposes of the game. World Wide Wrestling is the clearest example of that, as it literally maps “things you see wrestlers do in real life” to “things your characters do in the game” on a pretty granular level. However, since my goal is to give the players tools to build their own worlds – essentially – inside these genres, I’m not interested in replicating those parts so that they are manipulated in play. I think that’s how many of the proto-games I see (like contest entries) tend to work, where the designer has made some observations about how the genre they’re interested works, and so they turn those things into what the players do in the game. In carry, there’s no rules for fighting enemies, just rules for how much damage your unit takes in engagements and who’s to blame. Vietnam narratives have lots of firefights but they’re (to me) about taking or missing opportunities and the guilt and blame that goes with those decisions.

To bring this back to how role-playing works: I think role-playing

works best when you co-create something new together. I think it’s the creation of a fiction that you would have never imagined by yourself that makes role-playing so unique, and slavishly aping genre tropes gets you… those genre tropes. Using game mechanics to

direct a game towards the feelings that you get when you experience the inspirational genre is what interests me the most.

ET: So what you’re saying, if I understand correctly, is that intuiting emotional effects of genre tropes is more important than simply citing those tropes through mechanics. What advice do you have for RPG designers for reading their own emotional state while they experience other media, and then putting game mechanics on those emotions?

NDP: Well, it’s more important to me. I think there are plenty of

folks who want to replicate genre tropes in their games, and that’s

fine. There are some very well-designed games that deliver that, as

well. In terms of giving advice to people who want to design similar

games to mine, however, I think there’s a certain moment or sequence of moments in the fiction as you experience it that’s “the thing” you want to have come out of the game. It’s not always conscious, but if you’re having trouble with your design on paper or your playtests falling flat, it’s probably because you’re not hitting “the thing” yet.

So it may not be a specific emotion, but you have a certain emotional response to “the thing,” and it’s that response that’s important. When I watch Platoon (1986), what stands out to me is the iconic moment where Willem Dafoe rises to his knees for the last time before he finally dies, and the chopper with his fellow soldiers flies overhead. That moment encapsulates all the futility and tragedy of war, but casts it as a human drama, a result of decisions made by the men around him, not abstracted out to the level of political or military strategy. It is sad, but also deeply understandable at the same time. When I play carry, I do not want to necessarily replicate that moment in the fiction we create , but that mix of emotions and responses is what I want to get out of the game.

I do a lot of my design reflexively: by trying out an idea and then deciding if it works or not, so that internal yes/no measure one builds up by experience and paying attention to what you want out of the game on the emotional level. But identifying “the thing” targeted by your game design and analyzing, as an audience member, the source media for how it was delivered may be a useful strategy to try out. I wish I was methodical enough to do it myself – maybe I’d get more done!

Also, it’s worth pointing out that people who are already enthusiastic fans of the genre in question tend to more naturally or automatically”get it” than those who aren’t, and that can paper over some flaws in your design if you aren’t paying close attention. One of my goals isto share my love of a genre with other people. With World Wide Wrestling, I did my best to playtest with folks who were not active wrestling fans, and that was really helpful in giving me feedback about my assumptions and what worked to build wrestling stories and was did not. So, in terms of actionable advice, try to play with people outside your usual circles and pay attention to when the game is pushing them to do things that are “in-genre” whether they knew about it beforehand or not. That’s the good stuff right there.

–

Co-Editor-in-Chief of Analog Game Studies, Evan Torner, PhD (University of Massachusetts Amherst), is Assistant Professor of German Studies at the University of Cincinnati. His dissertation “The Race-Time Continuum: Race Projection in DEFA Genre Cinema” explores East German westerns, musicals and science fiction in terms of their representation of the Global South and its place in Marxist-Leninist historiography. This research has been supported by Fulbright and DEFA Foundation grants, as well as an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship at Grinnell College from 2013-14. His fields of expertise include East German genre cinema, German film history, critical race theory, and science fiction. His secondary fields of expertise include role-playing game studies, Nordic larp, cultural criticism, electronic music and second-language pedagogy. Torner has contributed to the field of game studies by way of his co-edited volume (with William J. White) entitled Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Role-Playing and Participatory Media (McFarland, 2012). He is also the co-organizer (with David Simkins) of the RPG Summit at DiGRA 2015 in Lüneburg, Germany. He can be reached at evan.torner <at> gmail.com.

One thought on “Inspiration and RPG Design: An Interview with Nathan D. Paoletta”

Comments are closed.