[This is the third and final part of a series on uncertainty in role-playing games. Reading earlier essays may be helpful in defining some of the terminology, but it is not required. Part 1 can be read here, and Part 2 can be read here.]

Epistemology – n. the investigation of what distinguishes what we know to be true from what we believe to be true.

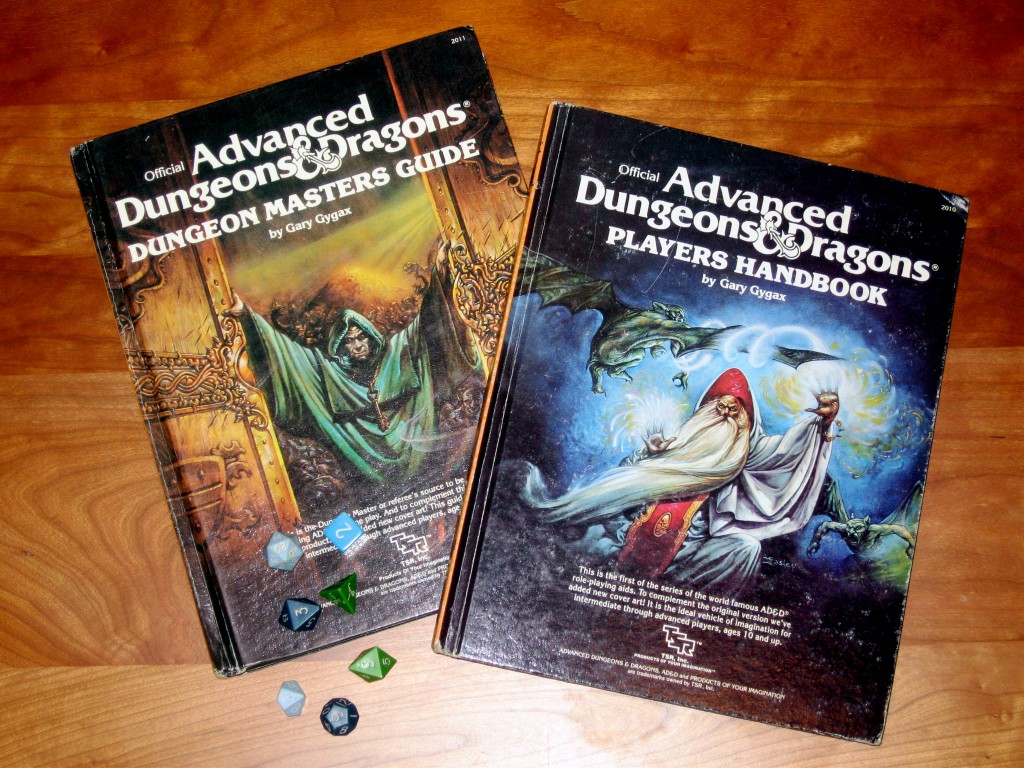

How do tabletop role-playing games (RPGs) test the boundaries of our knowledge? Or, to consult the epigraph, how do they suggest their own epistemology? We can address this fundamental uncertainty about our own capacity to know with the elements of uncertainty we find in the role-playing systems we play and design. This essay explains how the implementation of uncertainty in a variety of RPGs – Dungeons & Dragons (1974, 2014), Amber: Diceless Role-playing (1991), Dread (2006), Fiasco (2008), Montsegur 1244 (2009) – reflects the cultural and political milieu of the periods that produced them.

RPGs help player groups agree upon specific, suggested fictions that then generate pleasurable – and painful – emotion and cognition.1 Though the role-player her/himself will ultimately experience the medium as “first-person audience,”2 the role-playing group will nevertheless consent to certain rules and norms that will guide their behavior and their shared, negotiated fiction. If we’re all playing Dungeons and Dragons, for example, chances are that, before we even have entered the fiction of the game, we have already (tacitly) consented to the game’s races and their modifiers, to the idea that a character with a Strength stat of 13 has a certain probability of being able to lift 200 lbs, and that the dungeonmaster will get to frame the opening scene, which will likely be in a town or tavern. Of course, all players possess the capacity to say “no.” Within the significant arbitrating power of the listeners’ consent lies the real game or, as Apocalypse World (2010) designer Vincent Baker once put it, “all role-playing systems apportion [credibility,] and that’s all they do.”3

Role-playing game systems are thus caught up in some of the same paradoxes that plague the concept of certainty itself. As philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein asserts,4 to be certain you know is actually to doubt if a proposition is true and to verify its veracity anew. Yet our current language and culture surrounding the concept of “intelligence” proscribes our ability to admit ignorance. In other words, we frequently have to express certainty about a fact before we have verified it, or before we even have the language to accurately describe what the situation is. To be certain means to have doubted – with the necessary precursor statement “I thought I knew, but…” – and then sought out the “truth” for oneself.5 But certainty is a scarce resource within modern society,6 such that we often cannot even find a viable test for our own knowledge.7 If we look at Wikipedia for truth, for example, we find only crowdsourced knowledge to which many previous people have consented. We accept its propositions not because we are ignorant or uncritical, but because it takes too much time and energy to verify their veracity beyond a point.8

In essence, the search for even a provisional truth relies on a healthy sense of skepticism combined with a – perhaps falsely optimistic – general consensus on which to stand, a “presupposed certainty” that lets us explore the borders of the uncertain. In his work Uncertainty in Games, Greg Costikyan argues that we have culturally fashioned “a series of elaborate constructs that subject us to uncertainty – but in a fictive and nonthreatening way” which we call “games.”9 We craft artificial systems to experience emergent effects; we want to know what to expect, but not what will necessarily happen to us. Games themselves play with certainty, which means they tinker with the very mechanisms we use to form knowledge, and they even assist us with the transmission of cultural knowledge within a group.10 Role-playing games offer a somewhat narrower set of tools to nevertheless toy with our construction of knowledge, with their potential in this respect only beginning to be explored within the last two decades of RPG development. And with the absence of a solid win-condition,11 the satisfying outcome of an RPG hinges on a group of players adequately exploring – and being affected by – the uncertainty inherent in the game.

But by no means, as Ian Bogost argues,12 are games value-neutral in the kinds of uncertainty and fictions they generate. All games mediate the values and cultures that produced them. They can also be used for structuring and spinning information toward certain desires and interests. As a film, Triumph of the Will (1936) aesthetically persuaded its audience that the National Socialists in Germany constituted a unified political and military entity, as opposed to a number of bitterly divided power factions. As television programming, MTV music videos in the 1980s-1990s successfully convinced a generation of young people that a television network understood their style and interests better than they did. As portable video footage, the plethora of home-video documents of the Twin Towers attacks on September 11, 2001 helped instantiate a sense of overwhelming subjective, personal loss on the international level. So too can the medium of role-playing games, with their primacy of the fictive, reflect distinct cultural forces.

The rise of Dungeons & Dragons and its grid-based dungeon maps mirrors the early proliferation of computing and the hyper-quantification of society beginning in the 1970s. To succeed in Dungeons & Dragons is to conquer the algorithm, to arrest the forces of randomness. The urban settings of the White Wolf World of Darkness (1991-) games or R. Talsorian’s Cyberpunk 2020 (1990) highlight early 1990s fears about gang violence in post-industrial America and the disillusionment surrounding Baby Boomers selling out to corrupt finance capital. Success in these RPGs requires mastery over player uncertainty (by way of manipulating your peers) as well as the analytic complexity of the streets and their various dangers. Affect-laden knowledges from certain cultures and moments structure what kinds of games we create, and vice versa.

Drawing on previous analyses,13 we can see how epistemology plays a role in various games across the variegated 40-year history of the role-playing hobby. Dungeons & Dragons, produced by logics of the Cold War,14 projects the unknown into subterranean spaces, which we then begin to “know” by mathematically mapping them, killing enemies within them, and processing these enemies’ resources (i.e., their loot). Even character experience – supposedly their knowledge acquired from acting in the world – is derived from loot obtained in the early versions of Dungeons & Dragons. The game’s contours reflect a Vietnam War-era desire for Manichean good-vs.-evil categories, while also encouraging all the cold instrumentality of modern warfare: fighters will only use their highest-damaging weapon in conflicts, player-characters are encouraged to specialize in their specific dungeon-crawling capabilities, and enemies/traps ambush them like in the bush, giving no quarter. D&D player-characters are both heroes and vicious killers. Uncertainty centers not on who is being killed or how it feels, but how to kill it and what re-saleable treasures it might leave behind. That’s just the nature of the game and the way it structures knowledge.

Meanwhile, Erick Wujcik’s Amber Diceless Roleplaying was developed in the late 1980s, a period in which the savings-and-loan collapse in the States resonated with the general economic dissolution of the Soviet Union and the concurrent rise of China. As a game with no randomizers such as dice or cards, Amber centers knowledge on player uncertainty and the tricky political exigencies of a game world comprised of literally infinite worlds. If we even remotely accept the notion that there were such things as First, Second and Third Worlds (which is debatable, of course), then a game about scheming artistocrats with massive powers perhaps reflects the uncertainty about which “World” would wind up on top, whose vision for society was more viable, and what new enemies would their superpower tactics produce. The removal of randomizers beyond gamemaster fiat forces player-character responsibility for their actions, meaning that all consequences will likely hurt on a personal level. Characters act as global powers, but their pain is all local.

Speaking of “the local,” Jason Morningstar’s Fiasco from 2009 prompts player-characters to pursue petty, painfully local goals (e.g., “To get even with the scum who are dealing drugs in your town”) and then act on impulse, cognitively dissociating the player’s persona from the character’s. In an environment of performative online identities and a general collapse of generational optimism about the future, Fiasco permits players to troll each other in the fiction without much retribution, and leaves them the option of seeing any meaning in the game or just throw up their hands and echo the CIA Superior (J.K. Simmons) at the end of Burn After Reading (2008): “I’m f***ed if I know what we did.” Player knowledge is used to drive dramatic irony, as character ignorance produces the greatest sense of narrative anticipation.

Epidiah Ravachol’s Dread, that rare RPG that relies on performative uncertainty to determine narrative outcomes, treats knowledge the way many films noirs do: as directly correlating with danger and death. To know is to pull blocks successfully from the Jenga tower, and to pull blocks from the Jenga tower is to push one unlucky character toward death. The further one seeks to know what is going on and how to stop the imminent threat, the closer imminent death (in the Jenga tower’s collapse) appears. The Enlightenment project (“Sapere aude/Dare to know!”) becomes a liability as one seeks to escape the killer’s knife-blade or the horde of encroaching zombies. Narration itself gets mapped onto the characters’ bodies: it doesn’t matter where they happen to be (as opposed to D&D), or what political games they are playing with each other (as opposed to Amber, Cyberpunk 2020, or the White Wolf RPGs) – the next decision could get them killed. Whereas Morningstar’s game demands irony, Ravachol’s game demands intensity, a physiological response to ephemera mentioned. So just as media consumers in the 2000s increased their savvy-ness about genre convention and appreciation of narrative failure (Fiasco), they also sought virtual, immersive systems that would refuse to trivialize the fictional secondary worlds at stake (Dread).

Another concurrent example, Frederik Jensen’s Montsegur 1244 hybridizes the two affective modes of uncertainty: ironic and immersive. The game takes place at the time of the Cathar Rebellion in 1244 AD, during which numerous Cathar heretics were given the choice of renouncing their faith or burning at the stake. The story itself remains largely foreclosed: your characters will lose their collective struggle and take their individual fates into their own hands. One cannot become too attached to one’s character (even involuntarily) because of the remote setting and forced decision trees at the end. Nevertheless, the characters’ background stories and the actual scenes of the game compel players to emotionally commit to the outcome, with the full knowledge of the events and their moral weight applying pressure to the situation. The uncertainties, as with Fiasco, take place at the site of the player making meaning of their experience. In addition, gameplay itself focuses on small details like “a metallic taste of blood” or “a choking smoke brings forth tears” that allow players to interrupt other players’ narration, forming the basis of player uncertainty that rewards inter-player cohesion (so that you do not get your right to fictional positioning suddenly taken away from you.) The gestalt is a game that illustrates both our society’s exacting historical knowledge, as well as its contested narration and interpretation. We cannot “know” the Cathars; only experience (as a first-person audience) their emotions during their fateful decisions. We are prompted to experience human empathy at the level of 6 billion people, a massive scale never previously required. If we can use our cognitive knowledge of the Cathars to produce emotional “knowledge” in ourselves, then the system is (again) a process responding to an era’s concerns.

This essay promotes role-players to take a philosophical view of the systems they use to create certain fictions, given that these systems are fundamentally playing with the building blocks of knowledge construction itself. Co-creation of imaginary worlds is not an equivocal process, but intensely negotiated between different parties and subjectivities, all against a backdrop of social anxieties and cultural norms. The language of uncertainty gives us an opportunity to compare the different unknowns each role-playing game generates with the kinds of player-character knowledge required to resolve these unknowns in play. Role-playing games rarely have win conditions, but they do provide us with a platform to study how we arrive at the truth, and which truths interest us in the first place.

–

Featured image “Au détour du chemin, Bosdarros, Béarn, Pyrénées Atlantiques, Aquitaine, France” by Bernard Blanc @Flickr CC BY-NC

–

Co-Editor-in-Chief of Analog Game Studies, Evan Torner, PhD (University of Massachusetts Amherst), is Assistant Professor of German Studies at the University of Cincinnati. His dissertation “The Race-Time Continuum: Race Projection in DEFA Genre Cinema” explores East German westerns, musicals and science fiction in terms of their representation of the Global South and its place in Marxist-Leninist historiography. This research has been supported by Fulbright and DEFA Foundation grants, as well as an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship at Grinnell College from 2013-14. His fields of expertise include East German genre cinema, German film history, critical race theory, and science fiction. His secondary fields of expertise include role-playing game studies, Nordic larp, cultural criticism, electronic music and second-language pedagogy. Torner has contributed to the field of game studies by way of his co-edited volume (with William J. White) entitled Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Role-Playing and Participatory Media (McFarland, 2012). He is also the co-organizer (with David Simkins) of the RPG Summit at DiGRA 2015 in Lüneburg, Germany. He can be reached at evan.torner <at> gmail.com.