“Brasil, 1971. A seleção é tri, a ditadura está pior do que nunca e Roberto Carlos continua fazendo. Além de perseguir terroristas, a polícia está a caça da Quadrilha do Bicho, chefiada pelo homem conhecido como Tarzan, que vem roubando bicheiros nas principais capitais do país.”

“Brazil, 1971. Brazil is a third-time champion in the World Cup, the dictatorship is worse than ever, and the singer Roberto Carlos continues to be very successful. Besides pursuing terrorists, the police are also hunting the Animal Gang, led by a man known as Tarzan, who has been robbing bookies in the major capitals of the country.”

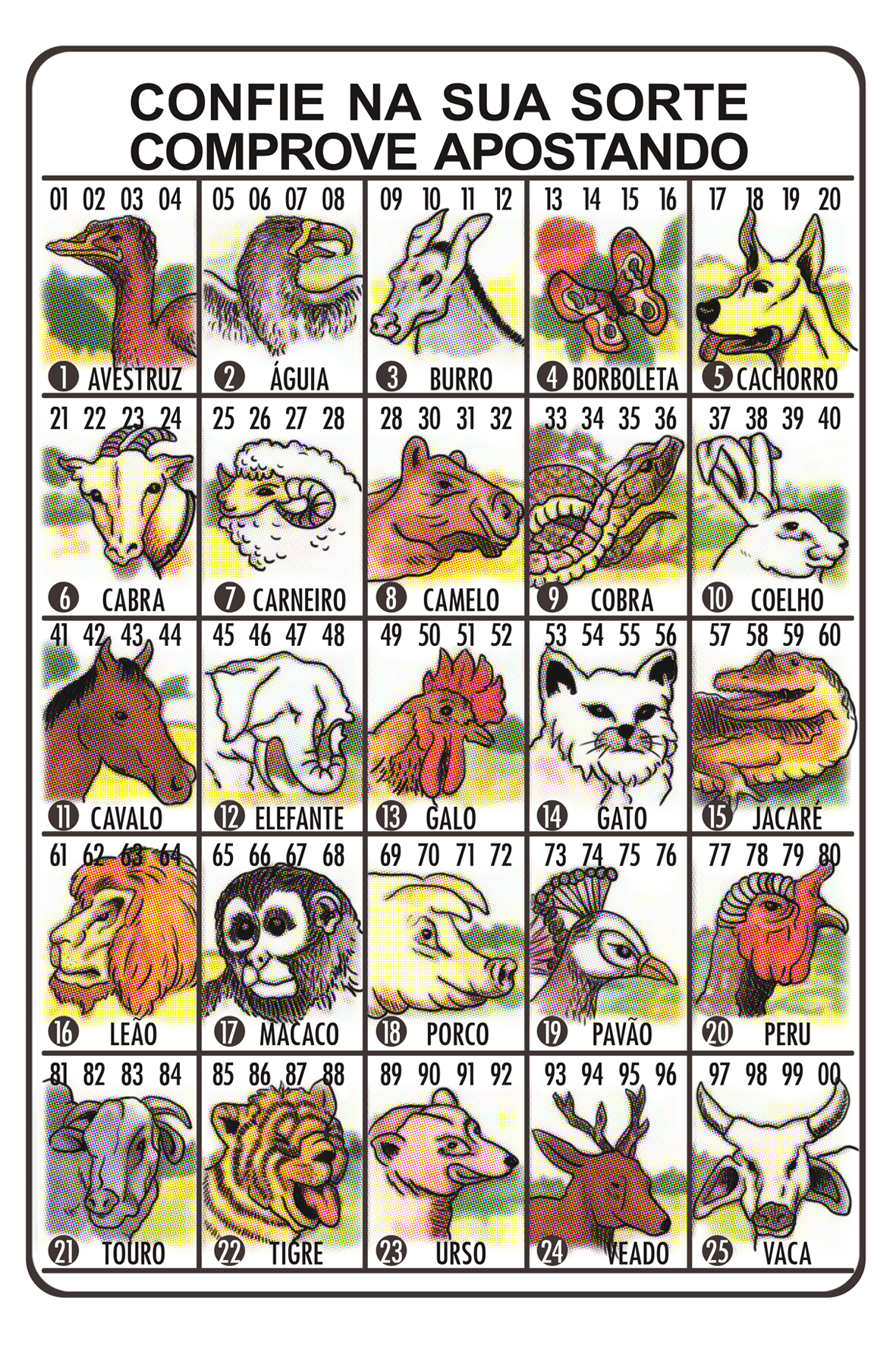

O Jogo do Bicho (The Animal Game), created by Luiz Falcão and Luiz Prado, is a two-hour chamber larp for eight people about (bad) luck, uncanny experiences, and what people do together when there is nothing to do. Influenced by Jeepform, Nordic Larp, and and other blackbox traditions, the game makes heavy use of metatechniques and is one of the first Brazilian larps (that we know of) in this style. We wanted to document this larp because we believe that it is a unique and interesting game, it is relevant to the regional and international larp communities, and it epitomizes Brazilian flavors. O Jogo do Bicho takes its name from the infamous folkloric and illegal betting game. The larp is set in Brazil in 1971, during our military dictatorship. At our first run, the setting was a bar, represented with tables and chairs, and 1970s music played on the radio in the background. Guns (represented by bananas), beer and “Cachaça”, and decks of playing cards and thematic betting cards completed the scene.

O Jogo do Bicho was first run in Belo Horizonte in April, 2014 at a festival called Laboratório de Jogos (Game Lab), aimed at a community of indie analog game developers, especially indie RPGs. Our larp attracted a wide variety of participants including roleplayers, game designers, larpwrights, an academic researcher on roleplaying, and a psychodramatist. We also had a diverse array of players from various states, such as Minas Gerais (where the event was hosted), São Paulo (580km/360 miles away), Rio de Janeiro (430km/267miles away), and Rio Grande do Sul (1.708km/1061miles away). There was even an international representative from Portugal (4406km / 2738 miles away, counting from Lisbon). It is interesting to note that all players in this run were men, which was not typical of the other activities we sponsored at the event.

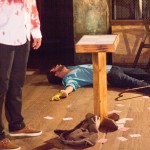

In O Jogo do Bicho, players represent freelance criminals (some of them in their first involvement with organized crime), hired by the bookie known as Tarzan. They commit a crime against another bookie, but the plan goes wrong and they find themselves, after the failed attempt, in a previously agreed-upon meeting place. The action of the larp takes place here, during the meeting of the characters as they await the arrival of their employer, which is meant to occur two hours after their arrival – the event that concludes the larp. The setting of the 1970s – with no cellphones – prevents players from communicating with this character and contributes to a sense of isolation for the group. The game is characterized by a sense of waiting and anxiety, as Tarzan never does actually appear (there may be some of Waiting for Godot in O Jogo do Bicho).

The aesthetic inspiration for this game came from the films of American directors Quentin Tarantino (especially the movie Reservoir Dogs) and David Lynch. Our research around the second director eventually fully absorbed us and inspired us to reframe the use of “key scenes” in larp (which is discussed in more detail later on).

After the first playtest, which was more in the style of Tarantino, we decided to dial back the use of referentiality to American cinema. In the search for new aesthetics to spice the game, we came across a recent news story about the bookie mafia. This theme seemed to fit like a glove and made the most sense with the mechanics and outline of our larp, even with the Lynchian influence. The Animal Game + David Lynch + 1970s: there was something a little Hotline Miami about that mix and we knew we were on the right track.

The setting of the1970s, the time of the bustling underworld of the illegal gambling game known as O Jogo do Bicho (The Animal Game), nurtured an aesthetic and thematic framework without equal. It was a time in which our generation did not live, but one that we approach with intense nostalgia: for good or for evil. A military dictatorship in one of its most oppressive forms, the national euphoria of a third-time win in the World Cup, colorful media saturated with tropical imagery, the political movements, the music, the fashion, the stereotypes of the time… We attempted to represent this rich aesthetic in our larp through the soundtrack, the costumes of the characters, and the familiar betting cards. The bar setting of O Jogo do Bicho is a familiar environment, but with a time shift that takes us out of the commonplace, the territory of comfort, and contributes to an experience of the uncanny, the strange/familiar, which helps build the atmosphere proposed for the game.

And why represent firearms with bananas? Representing guns in larps is always tricky. Nerf guns work well in adventure games. But realistic replicas are very difficult to be authorized in Brazil, and can bring some problems too. We wanted something more than a simple marker of a gun. We wanted something that would symbolize something in our larp. So Luiz Prado suggested bananas, which happened to be a national symbol when Brazil was under dictatorship. And the shape allows it to be held like a gun. Issue resolved.

For us, O Jogo do Bicho was an opportunity to push the boundaries of Brazilian larp. We based our creation of O Jogo do Bicho on some very simple assumptions. It should be a flashy larp, with an attractive theme in Brazil: the mafia. Such a “necessary zombie” should attract players to an unconventional experience. We also wanted the details of the plot to be determined at random from a deck of options that could be recombined freely. Finally, the “key scenes”, a common element in other Brazilian larps, would not be controlled by the organizers, but rather by the players.

Larp first took hold in Brazil in the early 1990s, alongside the popularity of Vampire: The Masquerade. The practice quickly consolidated itself, spreading through the country and incentivizing a well-diversified freeform scene. Some groups developed autonomy, tradition (like Graal and the Confraria das Ideias), and their own style. Today, most Brazilian larps are Vampire larps and other Mind’s Eye Theatre games, or other boffer larps. But freeform larps are growing in popularity, becoming at each turn a more relevant larp practice, both experimental and artistic.

In 2011, the group Boi Voador (Flying Ox) was the first Brazilian larp group to notably defend larp as an art form, influenced by the traditions of Nordic Larp and other nations outside of the Americas, such as in France and the Czech Republic. This instigated an explosion of more and more unique larps, new authors, and a decentralized community of enthusiastic players. In a context where the predominant larps were very traditional, with conventional units of time, space, and character, and predominantly influenced by commercial tabletop RPGs, Boi Voador started to experiment with the possibilities of the medium. The Brazilian run of Tango for Two (a Nordic larp), the discovery of the Norwegian Role Play Poems, and the original larps Caleidoscópolis (Kaleidoscopolis) and A Clínica: Projeto Memento (The Clinic: Memento Project) marked the first phase of research. In those attempts, the group experimented with breaking from the traditions of mimetic representation and the unities of character, duration, and form. A Clínica aimed to take larp seriously as an art form and push the production values to a more professional level than had previously been the norm in Brazilian larp. The game took an immersive approach influenced by the manifesto Dogma 99, with no violence in its plot, no simulation mechanics, and no permission for the players to go out of character during the experience. O Jogo do Bicho is the next step of this research process. While A Clínica (2011) searched for deepening of immersion and drama, the newest Boi Voador games are epic and non-illusionistic, in the tradition of Brechtian theatre.

We therefore adopted some specific criteria for the design of this larp:

- No secrecy: there are no secrets in the game, and the events of the game are not based on secrets. All participants may have access to all materials of the game.

- No distinction between organizers and players: the organizers also play, and the control and pacing of the game – usually responsibilities of the organizers – is divided equally among all participants.

- Narrative and structural control given to the players: the Confraria das Ideias, one of the most traditional larp groups in São Paulo, structures many of their larps with what they call key scenes, or narrative events, triggered by the larp organizers, to confer rhythm and movement. In O Jogo do Bicho, we removed this power from the hands of the organizers and instead, placed it at the disposal of any player. With the influence of our readings on the metatechniques of Jeepform and Nordic larp black box, these “key scenes” were strengthened and took on absolutely new functions in our game. In our game, a list of nine metatechniques was on a blackboard on the wall. At any time, a player could pick one from the list to initiate a new key scene. Some of these techniques interrupt the narrative flow and pull players out of characters (such as “pausing the game”), others add a dramatic event (such as a firefight or a round of betting), some temporarily change the mode of representation (such as having the players close their eyes and tell a collective dream one by one, or having the players temporarily represent animals), and some instigate a shift in narrative (such as having a player/character performs a monologue, or having two players/characters dance a waltz).

- Randomness: situation, plot, nicknames, characters… to eliminate the necessity of secrets built for the plot, to eliminate predictability, and to allow for a higher replay value, the majority of the plot elements in the larp are determined randomly, by drawing cards at random from a deck, a design element that allows for many variations of the game to be played. This includes the crime that was committed by the group (such as a kidnapping, the burglary of a suitcase filled with cash, finding a body at the meeting place), and for the creation of characters. The theme of chance is also evinced through the subject and title of the larp.

- Dislocation of the narrative / dramatic focus: The players do not enact the climactic and adventurous moments of the crime their characters commit. Instead, the action of the game is the waiting for the arrival of their employer to provide further instructions. But that event, too, does not occur in-game, as the larp ends at precisely the moment when Tarzan arrives. In this manner, the larp is set in an interstitial moment, between one happening and another. The focus is not, then, the development of an elaborate narrative about crime, but what happens between these characters during these two hours of waiting.

All these elements differ from the typical larps made in Brazil, which usually vary between narrative-centric and mechanics-light games, or RPG-like games where the story is occasionally interrupted in order to resolve conflict with character statistics (which is often mediated by an organizer). Our choices to randomize character generation and to combine the roles and responsibilities of players and organizers were somewhat innovative, as the use of metatechniques that disrupt narrative flow had not, to our knowledge, been used before in the Brazilian larp scene1.

For some of the participants in our run of O Jogo do Bicho at Laboratório de Jogos last April2, this was their first experience larping. Others had tried more traditional forms, especially Vampire. We were pleasantly surprised by the implementation of these new techniques, byt the commitment of the players, and by the successful functioning of the key scenes and metatechniques. The game we proposed, albeit quite different from the norm, was engaging to and assimilated by both veterans and first-time players. Even the most unorthodox metatechniques like “back in time” (where all characters go back to an earlier point in the game, regardless of what just happened, and move forward playing it differently this time) and “all players exchange characters” were performed freely and spontaneously by the participants, although there was, inevitably, some degree of confusion. Nonetheless, the response from the players was very positive, including inspiring João Mariano – our Portuguese guest – to run another Brazilian larp (Listen at the Maximum Volume) a few months later in Lisbon.

In retrospect, the setup of the game – that is, the lotteries that determine the characters and the crime they committed – seemed to us very lengthy. We feel the game could have benefitted from a more elaborate preparation with warm-ups and pre-game workshops designed to better guide the experience. We would also fine-tune the techniques to more smoothly transition all the players into the desired mood of the game. Some key scenes fulfilled this function exceptionally well (such as the collective dream and the five minutes of silence), but there were some variations that evoked over-excitement and squabbling (which have little to do with the desired mood for the game).

In O Jogo do Bicho, we experienced various possibilities within the medium of larp which broke from the main traditions of Brazilian larp. We were influenced by characteristics of larp in other countries, but most importantly, we found our own identity in this research. We will be running O Jogo do Bicho again on October 18th in São Paulo, where we plan to implement some simplifications in the setup and add warm-ups and pre-game workshops (as influenced by our experience with the Nordic larp White Death and some Brazilian larps by Luiz Prado). Thus, Boi Voador continues to push the boundaries of larp in Brazil and establish it on the map of the international contemporary larp community.

–

Featured image courtesy of the author.

All photos courtesy of the photographer, Luiz Lurugon.

Thanks to Telmo Luis Correa, Jr. for assistance with translation.

–

Luiz Falcão lives in São Paulo, Brazil, and is a visual artist, graphic designer, and multimedia instructor. Since 2007 he has been working with the creation and promotion of larps for Confraria das Ideias and since 2011 for the Boi Voador group. He coordinates the NpLarp – Research Group on Larp along with Luiz Prado in São Paulo and is the author of the book LIVE! Guia Prático para Larp (LIVE! A Practical Guide to Larp). In 2014, he published the article “New Tastes in Brazilian Larp”, about the history of larp in Brazil, in the book The Cutting Edge of Nordic Larp from Knutpunkt 2014.

You can follow him at http://nplarp.blogspot.com or contact him at luizpires.mesmo [at] gmail.com.

Good read!