Design matters. Few doubt it does. A game’s design is an immanent force that acts on its players, so that their play might produce emergent effects. “When we design [role-playing games],” says Eirik Fatland, “we are playing basically with the building blocks of culture. Not just our fictional cultures; real cultures as well … [directing] human creativity toward a shared purpose.” Game mechanics incentivize, constrain and afford certain specific behaviors so that the objective of the game is fulfilled. Prompts for player action, the incorporation of previously hidden information, and introduction of statistical probabilities preoccupy most designers of tabletop role-playing games (RPGs).1 In role-playing game studies, however, much of the conversation focuses on the “role” aspect of the activity: a player’s identity in relation to the character, the lines between reality and fiction, and the rationale for engaging in certain kinds of play.2 If designers are working with the “building blocks of culture,” then why aren’t we looking at how those building blocks produce certain types of play, as opposed to other types of play? This three-part essay on uncertainty in analog RPGs examines core variables of RPG design that produce the very diverse sorts of play experiences one finds in the medium today.

Some context is in order. I recently wrote a short piece about transparency in RPGs to highlight it as an active design element. In that article, I drew the distinction between transparency of expectation – or what the player can and cannot expect from a game, which lets players make informed decisions about play – and transparency of information – or what specific plot and game elements are revealed to the players over time. I concluded that increasing both transparencies confers increased agency on the player, but also increased responsibility over a game’s final outcome. The more you know, the more you must act sensibly on what you know. If I already know that Fiasco is a neo-noir game about ordinary criminals who create terrible trouble for themselves, then I’m not to going to play my character to “win” against the scenario. If I already know that Fiona’s character is a traitor, then I can use this information to play up my character’s loyalty to hers. This argument was made under the assumption that there should be more transparency in our designs, opening up lines of communication and making play much more egalitarian. As we know from Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We (1920), however, transparency in the form of glass walls to spy on one’s neighbors and absolute state surveillance could be seen as too much of a good thing. Surveillance activates our capacity to act, as well as stifles us. This got me thinking: what should players of a game know already in advance, and what elements cannot (and/or should not) be knowable? The border between what can be considered known and what cannot is certainly a “building block of culture,” as Fatland put it, and how we play with it can crucially influence the outcome of any game design.

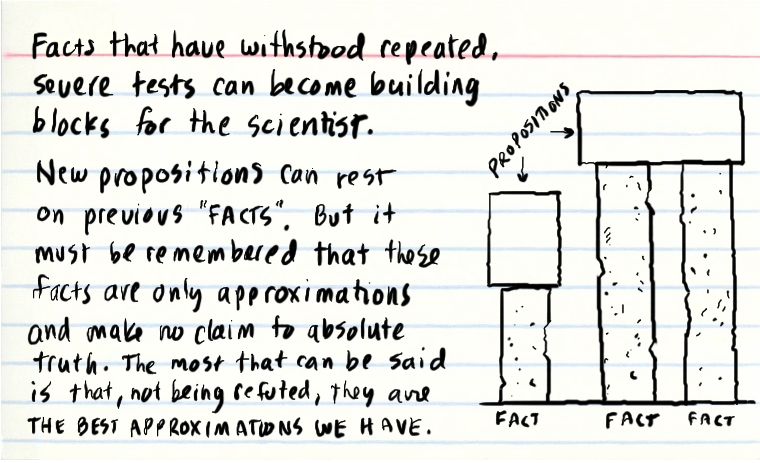

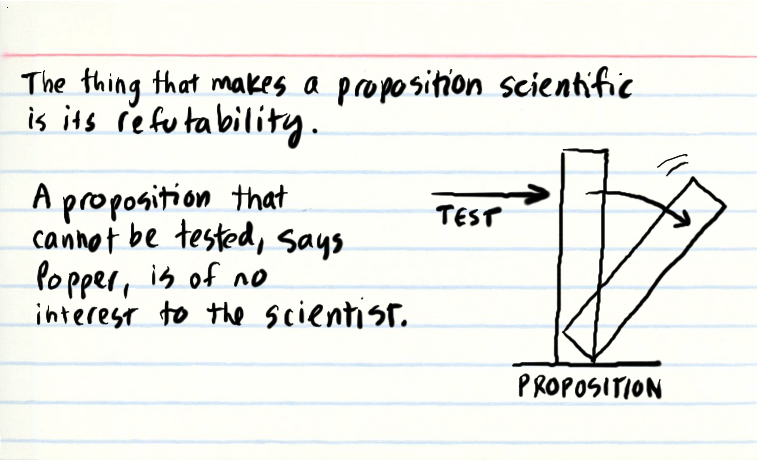

RPG design may, in fact, be creating different epistemologies that outline what knowledge is. An epistemology theorizes what can be considered a fact, belief, or opinion. RPG designers aspire to assist the fluid communication of facts, ideas and expectations during play, but must in turn abandon the notion that they can “control” the actual playing of the game in any given way. Countless RPGs still contain language such as “the rules are not the final word – you are,”3 or “never let the rules get in the way of what makes narrative sense.”4 Whereas other epistemologies in, say, scientific inquiry or legal studies hypothesize, verify, codify laws, and interrogate previous laws, RPG design presumes up front that every aspect of play – including rules – is relational to the group who plays the game. Hypotheses become impossible without sufficient fixed variables, and even the laws/rules themselves become entirely relative to the group in question. Playtesting is an attempt at paring down variables to see a game in action, but this presents an always-compromised view of a game’s general arc. If design matters so much, why do designers often disavow the design itself? Perhaps it is to acknowledge that the simple and relational delineation of diegetic truths – what some call “fictional positioning” – remains the most powerful tool in the RPG medium. Most of what a designer does is determine the aspects that are to be known and transparent in a given game, and how the unknown or hidden aspects reveal themselves to the players. The rest is up to the improvisational skills of a given group.

Talk of transparency and knowledge begs the broader question of the use of uncertainty in RPGs. If what we call “culture” is based on knowledge, ignorance, and practices that delineate the known from the unknown, then a designer’s deliberate use of uncertainty becomes a decisively cultural act. What varieties of uncertainty are required in different types of role-playing experiences, and how does RPG design attend to the different levels of uncertainty at work? If you think about it, analog RPGs in which “anything may be attempted”5 contain such variegated and nuanced levels of uncertainty that maybe Werner Karl Heisenberg would have considered them worthy of study. At a gaming convention, for example, organizers often have no idea who will be sitting with them at a given role-playing game table. When rolling dice, players don’t know if their character will succeed or fail. Costumes in live-action RPGs may tear or fall apart. Sick players may find themselves in moods that affect their actions in the story. If after 2 hours of fiddling about, the players (and characters) still can’t solve the Riddle of the Sphinx, and the end of the session looms near, how should the situation be handled? Uncertainty is baked into the role-playing medium. In some instances, we savor it – in others, we despise it.

It should come as no surprise that Greg Costikyan, a former RPG designer (Paranoia, Star Wars: The Role-Playing Game), has written a book-length essay entitled Uncertainty in Games (MIT, 2013).6 The book helps us to address questions about uncertainty, drawing on a set of perspectives which span the field of game design. See, we currently have a movement in game studies called “platform studies,” which isolates and examines how different platforms directly impact the aesthetic experiences created via their “software” (the games themselves). The movement has been able to use differentiation among platforms to draw wider conclusions about the possibilities of human cultural expression in an age of media saturation. On the other hand, Costikyan succeeds at performing a classic cross-platform analysis of the games he cites, focusing on universally shared characteristics across all games. Uncertainty in Games presents a concise argument about game design with numerous examples drawn from a host of different games: board, tabletop RPG, mobile app, console, etc. So maybe it is a Procrustean act to re-assert platform specificity using his elegant model but, heck, I want to take a closer look at analog role-playing games: tabletop, live-action and freeform.

Costikyan assigns uncertainty in games to eleven different sources, under the assumption that most games have multiple sources of uncertainty, and that the best-designed games are those that channel these uncertainties toward the fulfillment of the game’s objectives. This point is important, in that adjustment of given uncertainties in games affect what both the designers and players can expect from play, and how knowledge of and about the game might be co-constructed. If “fun is the desired exploration of uncertainty,” as Alexandre Mandryka recently posited, then new forms of knowledge – and new epistemologies – await us in these explorations as well. In the next post in this series, I will analyze several analog RPGs in detail according to these sources of uncertainty in an attempt to show just how useful this design-immanent approach to RPG theory is.

–

Featured image CC BY Mark Lorch @Flickr.

–

Experimentation and Design editor, Evan Torner, PhD (University of Massachusetts Amherst), is Assistant Professor of German Studies at the University of Cincinnati. His dissertation “The Race-Time Continuum: Race Projection in DEFA Genre Cinema” explores East German westerns, musicals and science fiction in terms of their representation of the Global South and its place in Marxist-Leninist historiography. This research has been supported by Fulbright and DEFA Foundation grants, as well as an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship at Grinnell College from 2013-14. His fields of expertise include East German genre cinema, German film history, critical race theory, and science fiction. His secondary fields of expertise include role-playing game studies, Nordic larp, cultural criticism, electronic music and second-language pedagogy. Torner has contributed to the field of game studies by way of his co-edited volume (with William J. White) entitled Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Role-Playing and Participatory Media (McFarland, 2012). He organized the Pioneer Valley Game Studies Colloquium in 2012, and helps organize JiffyCon, Origins Games on Demand, and Western Massachusetts Interactive Literature Society (WMILS) events. His freeform scenario “Metropolis” was nominated for “Best Game Devices” at Fastaval 2012 in Hobro, Denmark, and several other scenarios have been selected for the program. These scenarios constitute part of a larger book project that teaches German cinema through the medium of live-action games. He has also written prose for the Knutepunkt books as well as Playground magazine. He can be reached at evan.torner <at> gmail.com.

>> If design matters so much, why do designers often disavow the design itself?

There’s not a lot of difference between a “hobbyist” and a “professional” in TTRPG, even today, and the boundary between “GM” and “designer” is equally vague. There are TTRPG designers who consider the GM as an autonomous artist who will modify the rules as befits the application, and there are TTRPG designers who consider the GM as an idiot who needs to have everything spelled out mechanically. And then there’s everything in between.

Good point! I posed the question as rhetorical, but it stands to reason that the social positioning of TTRPG designers definitely has an impact here.

People today are so bad at giving praise, so here is one stranger saying “Great essay”.

Thanks, Rickard!

I hope you enjoy parts 2 and 3 as well.

FYI, the link to the WyrdCon piece on Transparency seems to be dead. (http://www.wyrdcon.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/WCCB13.pdf)