One of the most common questions that people ask with regard to the role-playing phenomenon is “How is role-playing like theatre acting?” Indeed, many role-players use the corollary of improvisational theatre in order to explain the concept to outsiders.

My goal is to investigate this correlation in depth, as the two psychological and performative states are clearly similar, if not identical. In what ways can we connect the role-playing experience with that of stage acting and improv? Where are the points of departure between these forms?

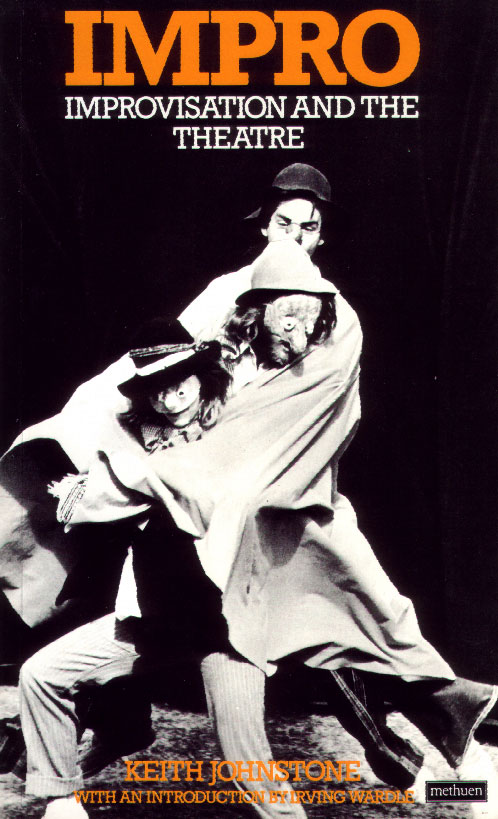

To explore this topic, I compare theories and thick descriptions from both role-players and actors. This essay focuses on connecting Keith Johnstone’s Impro1 connecting his experiments with mask work and other forms of improv with role-playing theory concepts such as immersion, dual consciousness, bleed, alibi, and possession. My analysis looks at how character immersion is conceived by role-playing theorists, and then turns to discussion of dissociation and the theory of mind, both of which may illuminate the phenomenon of character enactment.

The goal of this work is to bridge the gap between these performative activities, which have emerged as Western cultural forms in isolation from one another. As performativity and creative expression are essential aspects of the human experience, exploring the phenomenological states involved in acting, improv, and role-playing can help us understand the overall psychology behind the enactment impulse.

Distinctions

In many ways, the activity of immersing into a role-playing character is quite similar to both stage acting and improv. Yet the distinctions between these modes of enactment, however superficial, make a dramatic impact on the degree of creativity and agency of the performer.

Stage and screen acting often involve performing based upon a script and adhering to the physical and emotive instructions of a director. Improvisational acting forgoes the need for a script, as actors spontaneously perform creative roles in simple, usually short scenarios. Both of these forms of acting are usually performed for an external, presumably passive audience.

Role-playing is most similar to improv in that players enact spontaneous, unscripted roles, but for longer periods of time in a persistent fictional world. Additionally, role-playing involves a first-person audience rather than external viewership, meaning that the other role-players are the only audience members and are also immersed in their roles.2 Ultimately, we can consider these forms as cousins. Daniel MacKay suggests that scholars view role-playing games as a new, unique form of performance art, offering a detailed description of their aesthetics within this framework.3 Similarly, Jaakko Stenros and Jamie MacDonald have developed an aesthetics of action in order to describe the formal elements of the role-playing experience from the perspective of art and performance theory.4 Regardless of these distinctions, many similarities exist between these phenomenological states, as explored in the following sections.

Atrophy, Transgression, and Constraints

All adult creative activities require constraints of some sort. While childhood pretend play is more freeform in nature with little, if any, imposed rules, adults require structure and boundaries in order to engage in creative behavior. Keith Johnstone believes that one of the goals of society – and, specifically, of education – is to impose limits on the creative impulse of human beings.5 Mainstream society encourages its subjects to leave behind pretend play during adolescence. Indeed, Brian Bates explains how Western society once marginalized actors in the same way that role-players have been stigmatized in recent years. Because they enact alternate roles, actors were assumed to be untrustworthy, dangerous, and even criminal.6

Describing the demoralizing process of his own educational experience as a student and a teacher, Johnstone asserts,

“Most people lose their talent at puberty. I lost mine in my early twenties. I began to think of children not as immature adults, but of adults as atrophied children.”7

Indeed, many adults may think they have no creative impulse left at all when, in reality, their abilities may be simply lying dormant waiting for the opportunity to emerge.

In short, the adoption and performance of new identities and narratives is considered transgressive against society, which otherwise sorts individuals into specific roles and understandings of reality.8 Stage and screen actors transgress through their ability to effectively convey entirely new identities, performing narratives that may critique or interrogate socio-political norms. Improv actors transgress in their expression of chaotic, impulsive creativity, which often reveals taboo material from the unconscious and even expressions of deep spirituality and vulnerability.9 Drag performers transgress by temporarily shifting their assigned gender, often in provocative and outrageous ways.10

Role-players transgress in a way that mainstream society may find most alarming: they adopt persistent roles in a fictional reality for long periods of time. Outsiders often view this behavior as a rejection of the normative reality to which they all adhere, whereas role-players consider their enactments relatively safe and consequence-free. In the future, like acting, filmmaking, and novel writing, role-playing may become more acceptable as an understood creative form as it gains more positive exposure in media and academia.

All of these performative activities involve what Erving Goffman calls frame switching: when an individual shifts from one social role and performative “stage” to another.11 In each of these cases, the switching of frames is conscious and methodical, unlike when we change roles in daily life, e.g., from work to home, etc. Performers understand and play with the notion of switching social stages, behaving in a deliberate and sometimes provocative fashion. In order for these frame switching behaviors to remain possible in our society and for our previously established roles to become reinstated, we must ritualize these experiences by providing a clear beginning, middle, and end to the liminality of the performance.12

Other rules of engagement are also necessary for entrance into what game studies theorists call the magic circle of play.13 In stage and screen acting, performers must adhere to a set script written by someone else, the physical blocking and vocal elocution required by the director, and the time constraints of the format. These limits are imposed in order to convey the character and story as effectively as possible to an external audience. These limits are so exacting that Johnstone believes that they stifle the creative impulse of the actor almost completely. Instead, he advocates improvisation as the key to an actor’s self-expression.

However, even improvisation (improv) has certain constraints. Most improv performances are short, particularly in terms of how long a person immerses into a role or scenario. Although Johnstone often advocates for a serious tone, particularly in his Mask work, most people experience improvisational theatre as comedic, especially with the popularity of groups like ComedySportz, Second City, and the television shows Whose Line is It Anyway? The comedic elements allow for the breaking of taboos, emergence of repressed content and its joking dismissal as inconsequential or entertaining.

Role-playing games vary in terms of constraints by genre and form. Tabletop RPGs are bounded by play around a table and often include paper, dice, and other forms of abstract representation. Larps are bounded by time and space constraints. In addition to these physical boundaries, role-playing games also impose limitations on imagination and enactment through rules, norms of the play culture, and genre considerations. These limitations are imposed by the game design, the organizers, and to a certain degree, fellow players.

However, role-playing games offer a far greater degree of personal agency than either stage acting or improv. Because the constraint of an audience is no longer a factor, role-players enact their characters mainly for their own edification and in order to engage with one another. While some role-players prefer a dramatic style of play – often called dramatism or narrativism14 – with grand gestures and vocalizations intended to enhance immersion of other players, the audience still consists of fellow participants, not of passive viewers who expect to be entertained for their money. Therefore the expectations of performativity are different in role-playing, and the experience could be said to be more subjective and personal than grandiose and evocative.15 As Jamie MacDonald explains, theatrical performance is “beautiful to watch,” whereas role-playing is “beautiful to do.”16

Immersion and Method Acting

One intriguing connection between theatrical and RPG enactment emerges when comparing method acting to the “immersionism” style of role-playing. While method acting is most commonly used in stage and screen acting, which adheres to the above-mentioned limitations of pre-scripted and heavily directed characterizations, the “method” involves embodying lifelike performances by creating in the self the feelings and thoughts of the character. Pioneer Sanford Meisner described method as “living truthfully under imaginary circumstances.”17

This style of acting corresponds with the immersionist school of role-playing championed by theorists such as Mike Pohjola. Pohjola defines immersion as a form of role-playing in which the player assumes “the identity of the character by pretending to believe her identity only consists of the diegetic roles.”18 Petter Bøckman further explains that immersionism “values living the role’s life, feeling what the role would feel. Immersionists insist on resolving in-game events based solely on game-world considerations.”19 In this way, both method acting and immersionism require adhering to the external constraints of the aesthetic form while connecting as deeply as possible to the character. In future work, I will compare the specific processes and techniques involved in method acting with those commonly used by immersionists to explore further connections.

Dual Consciousness, Possession, Bleed, Mask Work, and Alibi

Examining Johnstone’s Impro in more detail, strong parallels exist between the ways in which improv actors and role-players describe their psychological states while engaged in play. While some role-play theorists such as Stenros, Pohjola, and MacDonald have certainly drawn upon acting theories to illuminate the role-playing experience, fascinating patterns emerge when comparing the language used to describe the phenomenon of transforming into character, especially when considering ethnographic research from role-players who are likely unaware of acting literature. This section looks at several concepts highlighted by Johnstone with reference to role-playing: dual consciousness, mask work, alibi, possession, and dissociation. These cursory summaries serve as an outline for future detailed research on these concepts.

Both role-players and actors speak of inhabiting a dual consciousness when performing a role in which the player passively observes the actions of the character to greater and lesser degrees. Jaakko Stenros describes it thus: “You have a sort of dual consciousness as you consider the playing both as real – within the fiction – and as not real, as playing.”20 The degree of consciousness on the part of the observational player can vary throughout the experience. Some players always have a strong sense of distance and control, whereas others seek to abandon their own identity to that of the role. Consider these two quotes from an improv actor and a role-player respectively:

There is a part of me sitting in a distant corner of my mind that watches and notices changed body sensations, etc. But it’s very passive, this watcher – does nothing that criticizes or interferes – and sometimes it’s not there at all. Then, it’s like the ‘I’ blanks out and ‘something else’ steps in and experiences. (Ingrid)21

My ideal, which I achieve occasionally, is to “become” the character fully—I’m just a little background process watching out for OOC [out-of-character] safety concerns and interpreting OOC elements of the scene for [the characters]. They are in the driver’s seat; I feel their emotions, have their trains of thought and subconscious impulses, and they have direct control of what I am doing, subject only to veto. (Anonymized role-player)22

In both of these cases, the player becomes a background observer to the character’s actions. In the second case, however, the player sometimes intervenes to maintain safety and “veto” the actions of the character if necessary.

In Ingrid’s description above, the “I” blanks out for a time, a form of amnesia in which the character takes control of the body. This process is called possession in some of the literature for both acting and role-playing theory.23 Johnstone asserts that such possession is difficult for many to achieve in his Mask work exercises, as their ego instinctively wants to retain control: “You feel that the Mask is about to take over. It is in this moment of crisis that the Mask teacher will urge you to continue. In most social situations, you are expected to maintain a consistent personality. In a Mask class, you are encouraged to ‘let go’ and allow yourself to become possessed.”24 Interestingly, a Mask class likely has a first-person audience rather than the static onlookers of traditional theatre or even improv performance, which makes it more similar to a role-playing exercise in terms of the flexibility of expression.

Brian Bates explains possession in a different fashion: “The traditional actor has a double consciousness; one part is possessed, the other observes and controls.”25 This definition indicates that the actor may still have some degree of control in a possessed state. Similarly, one of Nathan Hook’s participants in a phenomenological study of role-playing immersion explains: “I just let them borrow my body occasionally… [I let my character] take over almost entirely, with just a small background safety thread.”26 Ultimately, the degree to which a character during conscious enactment can completely take over a person is subject to debate, as is the length of time that such a possession can happen.

In other cases, the personalities of the player and character temporarily merge rather than one superseding the other. This experience may connect to a phenomenon that role-players call bleed, where the character’s emotions and thoughts spillover to the player and vice versa.27 Patrick Stewart, who immersed in the Star Trek character of Jean Luc Picard for seven consistent years with little time off, explains:

“It came to a point where I had no idea where Picard began and I ended. We completely overlapped. His voice became my voice, and there were other elements of him that became me.”28

In this extreme example of prolonged immersion, Stewart was likely experiencing what Whitney “Strix” Beltrán terms ego-bleed, where personality contents of the character bleed-out into the player and vice versa.29 In this example, Picard was not “possessing” Stewart, but rather the frame between the two personalities became weaker and less distinct over time.

Another role-playing concept regarding the distinction between player and character is alibi: the idea that the player is neither “present” nor performing the actions in game, but rather, the character is. Yet alibi is not necessarily equivalent to possession. Rather, alibi is a psychological mechanism that permits role-players to transgress normative social rules by playing a new identity in a fictional space without “real world” repercussions. In this sense, alibi is more of a defense mechanism than a dramatic shift in one’s psychological state, unlike dual consciousness or possession. Certain ritualized activities consciously facilitate alibi, e.g., carnivals, concerts, festivals like Burning Man, Halloween parties, acting exercises, and role-playing games.

Although not termed alibi in Impro, Johnstone describes giving improv actors permission to transgress their normal identities, thereby unlocking their creativity. Mask work encourages actors to dissolve their personality and wear a mask to elicit spontaneous, improvised behaviors. This process requires imposing alibi on the exercise: “I have to establish that they will not be held responsible for their actions while in the Mask.”30

In Johnstone’s experience, many of these mask behaviors resemble regressing into a child state, an animalistic state, or some other pre-verbal state that does not adhere to a fixed social identity.31 He explains:

“Once you understand that you’re no longer held responsible for your actions, then there’s no need to maintain a ‘personality.’”32

Interestingly, Johnstone believes that this absolution of responsibility is a “trick” and that the final step of the process after this “misdirect[ion]” is for actors to “become strong enough to resume the responsibility themselves. By that time, they have a more truthful concept of what they are.”33 In this way, alibi is a tool for granting acting students greater access to their own creative selves, which they should learn to accept and reintegrate into their self-concept.

Interestingly enough, Johnstone acolytes such as Alex Fradera have run mask exercises for larpers in minimalistic theatre settings, fusing the role-playing experience with the theatrical. Other experimental role-playing games such as the Nordic larp Totem and the blackbox larps White Death and A Beginning employ techniques similar to masking by limiting the verbal and physical expressions of actors. Through alibi and the magic circle, these experiences encourage role-players to explore interaction outside of the context of our normal social conventions such as speech and contemporary etiquette.

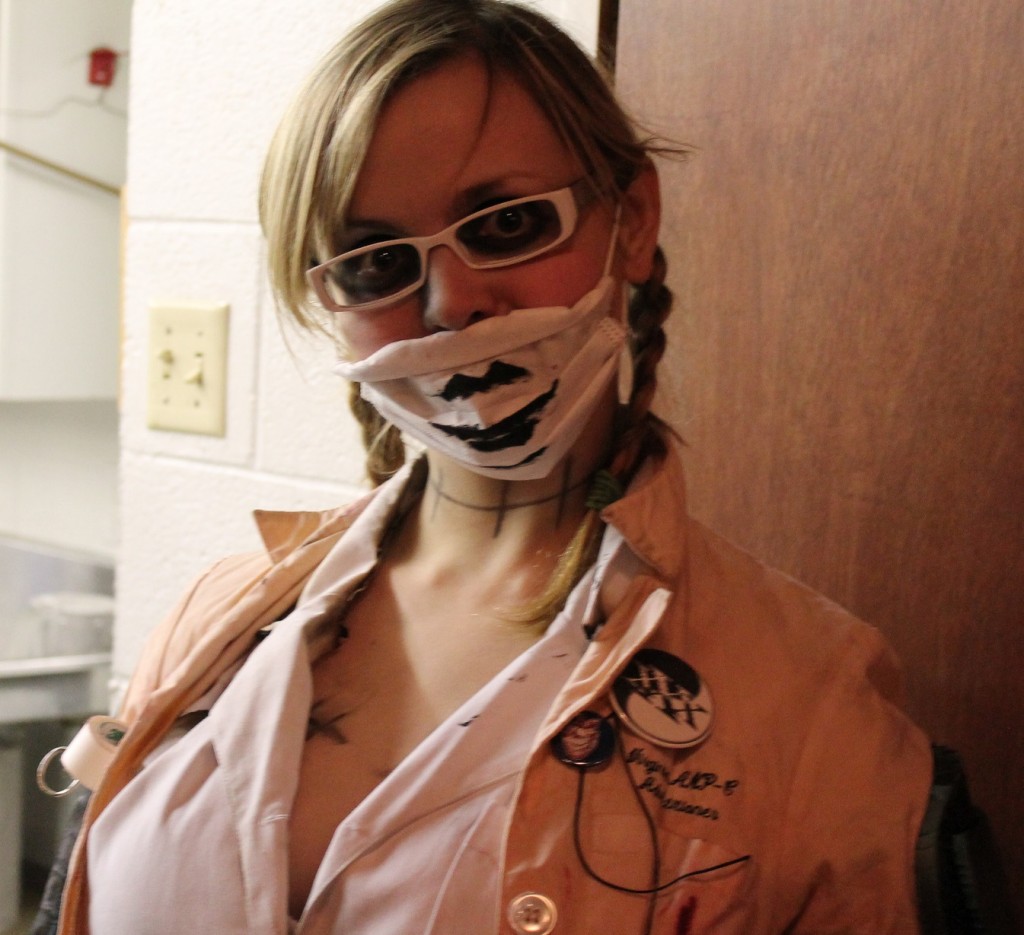

However, the concept of “masking” is more generalizable than these experiments in regression. To a degree, any form of makeup or costuming provides both alibi and mask for the player, allowing them to more freely inhabit the character. Both actors and role-players describe how the process of donning a costume and applying makeup is transformative in nature, an observation also made by drag queens when becoming their larger-than-life female alteregos.34

Furthermore, costumes, makeup, and masks can denote socio-political significance in the context of a persistent world. To use a filmmaking example, if a character is wearing the pope’s hat and garb in a movie about the Vatican, he evokes the social meaning ascribed to that station. Similarly, costuming, makeup, and masks “code” characters in larps in particular socially significant ways according to that fictional universe. In this sense, the mask often imposes a new social identity upon role-players while in game, one that may be as fixed and constrained as their existing mundane persona. In a persistent fictional world, characters are often expected to perform a consistent, realistic “self,” one that may be similar or different from their normative roles in society. Therefore, role-playing games are not entirely freeform spaces for creative expression; rather, they often adhere to some of the social conventions modeled from traditional society.

Finally, Moyra Turkington offers a role-playing theory that serves as an excellent bridge between each of these concepts. Turkington describes four degrees of immersion with relationship to the relative distance between the primary ego and the character: marionette, puppet, mask, and possessing force. The marionette refers to the player having the greatest distance and control over the character, whereas in the possessing force, “the player abandons a personal identity and surrenders to the character object as a goal of play in order to directly experience the full subjective reality of the character.”35 Not only does this description correspond strongly with the immersionism ideal, her choice of terms is particularly useful in the context of theatrical applications; marionettes, puppets, masks, and possession are all forms of theatrical enactment as well. These four categories offer a strong visual representation of how enveloped the player is by the character in terms of personal identification and ego control. Steering theory36 in role-playing offers another analogy, this time involving driving a car: is the player in the trunk, the back seat, the passenger seat, or behind the wheel?

Dissociation and Theory of Mind

While studying acting and role-playing theory is fascinating, we can also learn much from the field of psychology. Ultimately, I believe that these shifts from one mental frame to the next are forms of dissociation,37 as psychologist Lauri Lukka has also explained at length.38 Dissociation can take many forms, including feeling disconnected from one’s body (depersonalization), from reality (derealization) or experiencing amnesia, identity confusion, or identity alteration.39 In the latter case of identity alteration, the individual’s normative sense of ego identity shifts to another developed personality. Although identity alteration is a taboo subject due to its association with Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), this ability to shift identities appears to be a normal part of human consciousness, character enactment, and the creative impulse.

Indeed, Johnstone asserts that our personalities are far less stable than we would like to believe. The process of improv involves letting the ego dissolve and allowing other creative manifestations to emerge. These manifestations range from small pieces of imaginative ephemera to fully formed personality structures who can act autonomously from the original ego. For Johnstone, our presented, performed ego is one of many possibilities. He quotes actress Edith Evans, who states, “I seem to have an awful lot of people inside of me.”40 Shifting between these multiple “people” inside a performer is a conscious form of identity alteration, perfected by comedians such as Robin Williams, whose standup routine involved rapid-fire transitioning from personality to personality in an improvisational manner.

Johnstone further explains, “Many actors report ‘split’ states of consciousness, or amnesias; they speak of their body acting automatically, or as being inhabited by the character they are playing.”41 This reference to amnesia connects to the “blanking out” described by the actor Ingrid above, where the primary consciousness no longer remembers what occurred in character. The degree to which actors and role-players experience full amnesia while immersed in character requires further research, though the enactment experience is often described as ephemeral and confusing, as most liminal moments are.

Along with dissociation, Lukka invokes Piaget’s theory of mind to describe how such psychological constructs can develop. Most humans have the capacity to conceptualize the consciousness of another person, whether real or imagined. For example, at a certain stage of youth, we learn to imagine what our caretakers might think about a messy room and the consequences that might entail; we internalize a model of that authority figure’s consciousness within our own to predict behavior and act accordingly.

Fictional characters are no different in this regard. Stage and screen actors must create a theory of mind for their character in order to interpret the way that personality would authentically react to situations. Some actors invest a great deal of time writing backstories for their characters in order to flesh out elements not present in the script, a technique also employed by role-players. Johnstone describes the “interview” improv technique, in which actors interview one another in character, a process also performed in some role-playing workshops.42 These techniques not only expand the performer’s theory of mind for the character, but add a greater degree of personal investment in the creative process of enactment.

Summary

This article provide a cursory examination of ways in which scholars can compare the psychological states of acting and role-playing. Ultimately, the two states seem to closely resemble each other phenomenologically and probably involve identical psychological mechanisms, such as the theory of mind and dissociation. As Stenros and MacDonald have explained, the main distinction between the two forms is that stage acting generally involves performing for an external audience, which requires a certain degree of training, technical precision, structured movement, and scripted lines. Improv performed for an audience faces similar constraints.

Role-playing involves a first-person audience, meaning that the onlookers are the other performers, who are also immersed in their roles. Unlike most improv, role-playing involves immersing into a spontaneous role for an extended amount of time in a persistent fictional world. Players have a strong degree of agency within this framework, less constrained by an audience or director, but are rather limited by the format itself and the rules of engagement. Regardless of these distinctions, the connections between these two forms and the very act of frame shifting into different social roles can offer us fascinating insights into the nature of the psyche and its creative potential.

–

Featured Image: A Lascarian character in the larp Dystopia Rising: Lone Star. In this larp, Lascarians must wear costuming to cover their skin during the day, as their cave-dwelling race is vulnerable to the sun. This larper also chooses to use makeup as a form of mask to help immerse into the character. Photo by Sarah Lynne Bowman.

–

Sarah Lynne Bowman, PhD teaches as adjunct faculty in English and Communication for several institutions including The University of Texas at Dallas. She received her B.S. from the University of Texas at Austin in Radio-TV-Film in 1998 and her MA from the same department in 2003. She graduated with her PhD in Arts and Humanities from the University of Texas at Dallas in 2008. McFarland Press published her dissertation in 2010 as The Functions of Role-playing Games: How Participants Create Community, Solve Problems, and Explore Identity. Bowman edits The Wyrd Con Companion, a collection of essays on larp and related phenomena. Her current research interests include applying Jungian theory to role-playing studies, investigating social conflict in role-playing communities, studying the benefits of edu-larp, and comparing the enactment of role-playing characters with other creative phenomena such as drag performance.

This is something I wanted to do for a long time but never had the interest. Thank you for writing this article.

Yes, please.

Very much this!

You wrote: “… acting and role-playing. Ultimately, the two states seem to closely resemble each other phenomenologically …”

I claim the differences go still deeper. Larping can be considered as theatre (film, literature) turned inside out. Traditional forms of expression search for the form that best expounds the content – “here’s a story, how shall we tell it” – are Rowling’s novels the best way to convey the Potter story? (Which also explains why adapting books to other media often must change the story – outside of pandering to public, that is.) Meanwhile larps use the story (e.g. about a Wizardry school), as vehicle for the real content which is the participation, the interaction between players. Ofc we want interesting settings, for various reasons, but larping _as_such_ actually is about is the meeting of characters/players. The story (regardless of interest) is just an excuse for creating the meeting place. That’s also the reason why larps don’t need closure, the fun part is doing it, not finding out whodunnit.

I have a question about the theatrical role playing game do you buy the game so that the person is able to get the money for game

Although Sanford Meisner did say ‘acting is living truthfully in imaginary circumstances’, his approach was not the ‘Method’.

The Method is Lee Strasberg’s work