“We were each willing to play. We were each willing to play that particular game. We were each willing to play with each other. We arrived at a well-played game because of the way we combined with the game.”

-Bernard DeKoven, The Well-Played Game (1978)

Bodies at Play

In Milton Bradley’s Twister (1966), players are contorted at the beck of a spinning dial. Arms and legs knot together as uncomfortable glances are exchanged. Without prejudice or modesty, the bodies of its players are compromised. When the game first appeared, it caused a sensation. Competitors accused Milton Bradley of selling “sex in a box” and Sears Roebuck refused to sell the game. These days the game has traded such controversy for awkward giggles in church basements. The tyranny of the game’s dial—overlaid with two circles for both appendage and position—seems almost quaint. The physical bodies so easily manipulated in Twister have given way to more elaborate social contortions.

In games one can readily find all manner of physical and intellectual pretzels. Indeed, the uncomfortable entanglements found in Twister have become—if now metaphorically—a hallmark of contemporary game design. While there are many ways to understand the complex social spaces that games facilitate, I believe there is much to be gained from understanding games as networks of feeling. Here I mean to invoke Raymond Williams’s paradigmatic “structures of feeling” which describe the murky space between articulated ideologies and emotive response. Though evocative in the abstract, Williams’s term contains a basic flaw. As literary scholar Mitchum Huelhs has noted, “The problem with [Williams’s] term, and with deploying it critically, is that by definition it names an ambiguous configuration of the social that has not yet fully emerged.” While this may be true of the social experiences and configurations towards which Williams directed his analysis, games provide a far more tractable subject. Games have rules that inform the affective responses of their players. They are sites of what sociologist Evan W. Lauteria has called “affective structuring.” That is, a game’s affective responses are informed both by the other players and, critically, the game itself, which organizes the relationships between the players and the way that they are able to interface with the game-state.

Here the abstract and the embodied come into contact. For, if a player position is an abstraction (that is, a subject position created by a system of rules), it is one anchored by our affect and rooted in our flesh. Whatever their digital or analog footprints, games are bodily experiences. We inhabit the games we play. Our bodies interface with their components. Eyes search those of our opponents. Hands grip controllers until the tensed muscles seize with exhaustion. It is this embodied quality that makes the language of affect so useful when it comes to understanding games. So often games, especially multiplayer games, are understood merely as systems of rules. Although this proceduralist lens provides many insights into the nature of games, it tends to obscure the experiences of players and the emotional dimensions of play. Games allow us to occupy new and strange positions of affective entanglement. They offer an exceptional space of unlikely dependencies and interrelations. Indeed, such entanglements have become a hallmark of what a game is.

As has been noted in recent years, the world of non-digital games has experienced a renaissance both in terms of popularity of specific titles and the creation of new titles. However, critics have been less vocal about the specific dimensions of this renaissance. What kinds of games is it producing? What kinds of interactions are being generated? I would like to suggest that the chief design innovation revolves around the way the decision space of a game seeks to organize the feelings of its players. Not only has this engagement with feeling helped foster the revolution in game design, but it also continues to generate ever more sophisticated and reflective designs that continue to investigate the tangled feelings of players and the shared activity that continues to bring them back into the space of the game.

In this article, I want to consider the affective possibilities and consequences of contemporary board games. I begin with a discussion of Klaus Teuber’s Die Siedler von Catan (1995). Teuber’s design is something of a foundational text of the contemporary board game design. Using Catan as a lodestone, I want to draw on the vocabulary of affect studies in order to reorient how we talk about games, in hopes of better understanding why Catan proved to be such a phenomenon. From there, I will consider a recent trend in the subfield of historic wargames, where convention has been upended by the COIN (COunter INsurgency) game system by Volko Ruhnke. Rather than focus solely on military affairs, Ruhnke’s games reproduce the political tensions surrounding armed conflict and ask the players to inhabit positions of moral compromise in the interest of historical simulation. I end with brief discussion of Avery Mcdaldno’s storytelling game The Quiet Year. The Quiet Year pushes on the limits of the game as an engine of affect and asks hard questions about the power of affect and the formal limits of games to understand our knotty feelings.

Colonization and Community

By now, Klaus Tueber’s Die Settlers Von Catan requires little introduction. As of 2014, the game had sold more than 18 million copies. These figures dwarf those of any other similar design published in the past thirty years and are growing so quickly that, according to Mayfair, the game’s US publisher, the franchise is poised to become the biggest game brand in the world. For gamers who have come of age since its publication, Catan served as a gateway into the broader world of contemporary board games. And, in an industry often defined by innovation and novelty, Catan continues to be played and to inspire new titles.

Catan’s popularity is a consequence of the way the game structures the feelings of its players, but this affective focus is not readily apparent from the game’s setting. The fictional island of Catan is an abstract location. There is little backstory, and the game’s art, while evocative, is inspecific. The game offers its players only the spare outline of a story: there is an island and you are its settlers. Given the game’s generic setting, its popularity speaks to the strength of its design. For, as unremarkable as that little island of Catan might seem at first glance, the game that takes place on its shores is a riveting exercise in the management of dependency and the affective possibilities of game design.

Before looking at some specific elements of Catan’s design, I want to consider some formal qualities of games themselves. In the critical discourse around games, there is some considerable debate as to what a game is. In anthropology, a game is often defined as a form of structured play. This general definition allows for considerable wiggle room as the systems that structure play may take many forms. For instance, in game designer and scholar Bernard deKoven’s view, a game is an emergent artifact of play, negotiated by its participants in the interest of cultivating a shared experience. Under these rubrics, it becomes rather easy to think of a game as only a mathematical abstraction that exists virtually in the minds of its players. However, we should remember that games are also defined by their particular manifestations in digital and non-digital spaces. All games have an aesthetic footprint. Their aesthetics, like the rules that structure their play, are essentially political in that they organize the relationship between the players. This management carries with it an affective charge. For, if games structure play, so too do they structure feeling.

Catan’s interest in the structuration of feeling is built into the core of its design. The game’s demands seem simple enough: Catan tosses its players on an island and asks them to build a network of roads and settlements in a race to domesticate their surroundings. At first view, the game would seem to be an exercise in Randian objectivism, complete with terra nullius. However, in Catan players need one another, especially in the early stages of the game. The primary currency of the game is found in its five resources: wood, bricks, ore, wheat, and sheep. These resources are drawn from the island based on the location of the players’ settlements and cities. Here players encounter important complications. First, players begin the game with only two settlements, which are placed on the vertices of the map’s hexes. This gives them a maximum initial footprint of six hexes out of the island’s nineteen. Because of the random distribution of the map tiles, it is unlikely that a player has access to all five resources at the start of the game. Moreover, players tend to specialize in a particular good as the construction of far-flung settlements with access to new goods is often resource intensive. This specialization is complicated by the lack of a common medium of exchange. Unlike Monopoly (1903), there is no single currency. Players are forced to barter, and, from the first turn of the game, networks of dependence take shape.

Dependency is an important engine of affect. As infants, we enter the world in a total state of dependence and much of our emotional range is cultivated under its influence. Evolutionary psychologists have emphasized the ways that this early relationship informs our emotive range and provides the groundwork for later, more complicated networks of feeling. Games replicate these networks. The quarterback on a football team leads their players just as a manager might be responsible for their employees. These structures provide a frame for affective response. In other words, feelings are muted or amplified depending upon a subject’s position within a broader structure of dependence. Though a subject may simultaneously participate in several networks, the various structures of each network are largely fixed. For instance, in the student-teacher relationship, the student occupies the position of vulnerability and dependence. Of course, this structuration doesn’t preclude transgression. A teacher could certainly forfeit the affective safety of their position or undermine it. Still, even in such a scenario, the roles could still be reinstated in some fashion. In this way, the various networks of dependence that exist in society provide both positions of strength and vulnerability: we can lord over our own children, and yet still retreat into our mother’s arms.

Catan never allows such networks to ossify. Instead, the interpersonal relationships in Catan are always mutating. Their constant flux is built upon two specific elements of the game’s design. First, the players are always oriented towards the victory condition. The game ends the moment a player secures ten points. A player’s score is totally transparent, and therefore looms large in any negotiation. Secondly, the system of interaction in the game is highly regulated. Only the active player can initiate trades and there must always be at least one good exchanged by the two trading parties. This stops gift giving and creates a constant circulation of goods. Furthermore, the game also routinely (and randomly) culls player stockpiles, forcing players to do as much as possible with what they have at that moment. These pressures brutalize the players. Friendly relationships between players rarely survive more than a few rounds. Good play is opportunistic and cutthroat. Players will sometimes need to collude to stop another player from winning, but will soon find their alliance disintegrate.

In practice, this gives the game a tremendous range of feelings. Traditional games such as chess, Risk (1957), or Monopoly are purely adversarial. Though teamwork is possible, the game’s rules afford little opportunity for direct collaboration. This limits their affective scope. Catan, in contrast, forces players to navigate a much broader range of feelings. If Catan paved the way for the renaissance in game playing in the 21st century, it was a path paved with the charged feelings the game creates.

Affect goes to War

Catan is not the only game that has attracted recent attention in the mainstream press. In early 2014, The Washington Post published a feature length piece on a new type of series of wargames. These games traded set-piece battles for meditations of political will and counter-insurgency. The purely adversarial positions of classic wargame design were exchanged for complicated relationships and shifting alliances. What’s more, the games made no attempt hide their subjects. Unlike the sanitized colonial narrative of Catan, these games were upfront about the violence they sought to represent and made no apologies about the uncomfortable directions in which they pushed their players.

The COIN Series games are the brainchild of Volko Ruhnke, a CIA national security analysis. Ruhnke began designing games in the 1990s as an extension of the simulations he ran for his coworkers. His first widely-released design, Wilderness War (2001), covered the Seven Years War in North America and paid particular attention to unconventional warfare. The game was published by GMT Games, the largest wargame publisher in the US, and was met with immediate critical acclaim. Several years later Ruhnke pitched an idea for a new project to GMT: he wanted to make a series of games on modern counter insurgency. It would begin with a title on early 90s Columbia that would cover the interplay of the Colombian government, the drug cartels, the FARC, and right wing paramilitaries. The topic produced some anxiety, but eventually GMT agreed to pursue the project. It proved to be a shrewd decision. The resulting design, Andean Abyss (2012), was so successful that it spawned three sequels covering Afghanistan (A Distant Plain, 2013), Cuba (Cuba Libre, 2013), and Vietnam (Fire in the Lake, 2014). So far every COIN game has sold out and several new titles are planned in order to meet demand, as indicated by preorder information on the GMT website.

Surprisingly, the horrifying subject material of these games, which can include kidnappings and suicide bombings, is a novelty in wargaming. Though all wargames concern violence, many find ways of burying the gruesome details of war. As military historian Philip A. G. Sabin notes, “war games deliberately downplay the dark side of war. Casualties or destroyed units are usually removed cleanly from the board, with no simulation of the grisly aftermath in terms of the dead and wounded.” This tactical ignorance reflects the focus of the game. Wargames are not so much about war as they are about a specific part of war. The concerns of wargames tend to revolve around issues of supply, command and control, morale, and battlefield tactics. Anything outside of these interests is either abstracted or ignored outright, including the bodily violence and the more complicated elements of a conflict’s political context.

Ruhnke’s COIN games take a different approach. Though their scale doesn’t allow for an extended focus on individual acts of violence, the games make no attempt to hide the ugliness in war. Indeed, players must confront it directly. This confrontation is staged mechanically. The COIN games are card-driven games (CDGs). In CDGs, a player’s possible moves are informed by the play of cards. This dramatically expands the representational possibilities of a game design. For instance, the various moves in chess are limited by the fact that there are only six different types of pieces. In contrast, there are 72 unique cards in Andean Abyss. By housing the complexity of the game’s rules in a deck of cards, the general course of play is free to move smoothly. On a turn a player will be confronted with a card. They may choose to ignore the effect of the card and do one of a handful of actions, or they can capitalize on the event. In practice, this keeps all players focused on their various interactions and the possibilities that the present card offers. The turn’s current card will always be the central object of attention. This has a way of unifying the game. Though it is a CDG, players do not maintain separate hands. All eyes are on a single card, and, it is through those cards that the story of the game is told.

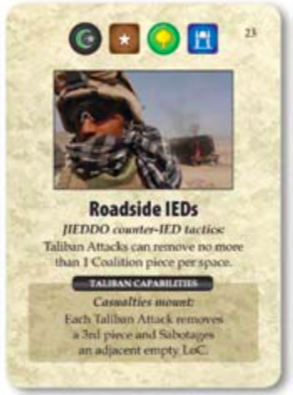

The cards themselves seem sensitive to this attention. Consider a card from A Distant Plain (pictured above). The card concerns the use of roadside IEDs. However, rather than reproduce a photograph of the device itself or a technical schematic, the card’s illustration is immediate and raw, picturing a close-up of a soldier’s face in the aftermath of an attack. Furthermore, the photographs chosen for the cards in A Distant Plain are usually morally ambiguous, opting for a journalistic ethos that seems invested in capturing the truth of a moment over one that might glorify the action depicted. This immediacy is significantly different from the classic wargaming aesthetic that privileged clarity and simplicity over immersion. The landmine piece from Milton Bradley’s Stratego (1960) offers essentially the same effect. However, its design encourages players to think in the abstract about the conflict. The violence it represents is cartoonish, playful, and, above all, unthreatening to its players.

Ruhnke’s games are both serious and threatening. They want to pull players into their dark and complicated decision spaces. In his piece in the Washington Post on Ruhnke, writer Jason Albert noted how, during play, “[t]he palpable discomfort among [players] brings [Ruhnke] joy. It means he has done his job.” This discomfort extends not only from the events depicted on the cards but also how the game structures the relationships between the players. With some exception, the COIN games are designed to be four-player experiences. Every player has a specific set of relationships with every other player, and these relationships are never simple. The tensions of A Distant Plain revolve around two uneasy alliances: the Coalition and Afghan government on one side and the warlords and the Taliban on other. Though the relationships are more rigid than in a game like Catan, they are designed to maximize the players’ vulnerabilities to one another. Players, even those with a clear advantage, feel exposed. This vulnerability heightens the their sense of immersion and the affective responses that follow it. Albert pays particular attention to these responses in his article, noting how “A subtle movement—pieces slid from Nuristan province to Kabul—is met with tensed shoulders and exhaled expletives.” These observations appear to be somewhat common. A quick perusal of the critical reception of Ruhnke’s games yields dozens of instances of affective entanglements like Albert describes. Judging by this reaction, it seems that the COIN series was successful in torqueing the affective networks that make people play in the first place. Though the restaging of counter insurgencies in the developing world is undoubtedly a political project, Ruhnke seems far more interested in a dialectic between the players and the game itself. In this sense the game is not meant to be prescriptive but instead provide a set of systems for exploration. Ruhnke appears to be asking players to never forget the context of their experience. The game seeks to pull its players in, but also to allow them to see beyond that immersion. Players are competitors and also fellow actors, able to view a situation holistically while working within it.

Of course, in order for this fraught experience to be generated in the first place, the game demands that players push against one another. Like Catan, the game’s victory conditions provide the central tension of play, and the game’s design needs those tensions in order to generate its narrative. Without them, the design sits like a boat in irons. The “game” as an affective form, can only manifest through play. Like stage-acting, this demands players put themselves in a position of vulnerability. But the rules of the game are not a script. Players are at once then both actors and writers, working within a designed space to produce something larger than the space itself.

Post-Player Affect

We return where we began. Games structure our interaction, and many new designs seem intent on heightening the affective component of our play. Yet, as innovative as these modern games are, certain formal constraints seem to remain. In order to play a game, the players must divide themselves. They may have arrived at the table as a group, but the game splits them.

This is not necessary. I want to end this piece by turning to Avery Mcdaldno’s The Quiet Year (2013). The Quiet Year has no peers in the contemporary tabletop gaming landscape. The design offers only gentle guidelines as to the limits of the game’s decision space. Over a variable number of turns—determined at random by an end-game card shuffled into a deck so that the ultimate length of the game is unknown to players as they play—players attempt to collectively build a community after some unspecified disaster. Significantly, players are not even given a chance to react to this peculiar setup, as unlike the majority of board games, table talk is expressly forbidden in The Quiet Year. Instead, players can only communicate in very limited remarks and only by drawing on a shared map. Conversation is impossible.

Yet, The Quiet Year is a game that directs its attention wholly on the question of feeling. Here the game makes two related interventions. First, it decouples players from the specific characters that may emerge through play. The rulebook is explicit on this point:

“We don’t embody specific characters nor act out scenes. Instead, we represent currents of thought within the community. When we speak or take action, we might be representing a single person or a great many. If we allow ourselves to care about the fate of these people, The Quiet Year becomes a richer experience and serves as a lens for understanding communities in conflict.”

Here The Quiet Year appears to be disrupting one of the most sacred elements of game design: the player-position relationship. Games usually provide players with somewhat stable thematic anchors through which they can understand their own position within the game. In Catan a player is a particular group of colonists. In a COIN game, a player might be a set of insurgents. In either case, the player is tethered to that position—their fortunes rise and fall with the single avatar or group to which they have been assigned. But The Quiet Year doesn’t allow for this bound to form. Players instead are encouraged to flow through different subject positions or “currents of thought.”

This decoupling leads directly to The Quiet Year’s second intervention. The game lacks victory conditions. Players can achieve neither victory nor defeat. The game simply ends. A victory condition is usually an essential component of game design. It is the death-drive that pushes the game towards its conclusion. It gives the players their motivation and the game’s narrative its dynamism. A victory condition also fosters a sense of investment in its players that, in turn, can cultivate their affective responses. Players rejoice precisely because the course of play enabled them to meet a goal outlined by a victory condition. These conditions are engines of feeling.

The Quiet Year contains no such benchmarks. This may at first seem to make the game a strange, affect-less space. But, in practice, the opposite is true. Without explicitly stated guidelines as to who the players might embody and what their goals are, players are encouraged to explore a broader affective space. Yet, this open space is rigorously curated by the game’s rules and its severe communication limits. This means that the central tension of The Quiet Year comes not from the attempt to win, but instead, the desire to be understood. It is this desire which structures the player relationships and generates feeling.

In considering three very different games over the course of this article, the management of affect is clearly a central element to the design. But, while the relationships between the players and the affective possibilities of those relationships are largely informed by the rules of the game, often it is the victory condition which determines which affective networks will dominate play. Games can make us feel, but, so too can they numb us to each other’s feelings. In this sense then, the victory conditions in a specific game serve to mute other (and potentially richer) player relationships. Without this drive to win, players are left to explore what remains, a complex knot of desires and hopes and fears, a network of affect in which to play.

—

Featured image “Networking” by jairoagua on Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA.

—

Cole Wehrle is a PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin where he has taught courses on subjects as varied as video games, film, and romantic poetry. Most of his research focuses on the relationship between the British Empire and the Victorian novel and how narratives were able to make the world seem like a smaller and more knowable place. He served as a design specialist for the Digital Writing and Research Lab (http://www.dwrl.utexas.edu/) at UT and is the co-editor of Culture Bytes Back (http://www.culturesbytesback.