The year is 1994: Bikini Kill is wailing “Rebel girl / When she walks, the revolution’s coming” while business women in shoulder-padded power suits purr about “having it all” In a basement in rural Canada, an intense argument unfolds:

“You have to put another zit sticker on! You didn’t call a boy and tell him something gross!”

“Cuz the phone is cut off! And we’re running out of zit stickers!”

“Still counts! Draw one on!”

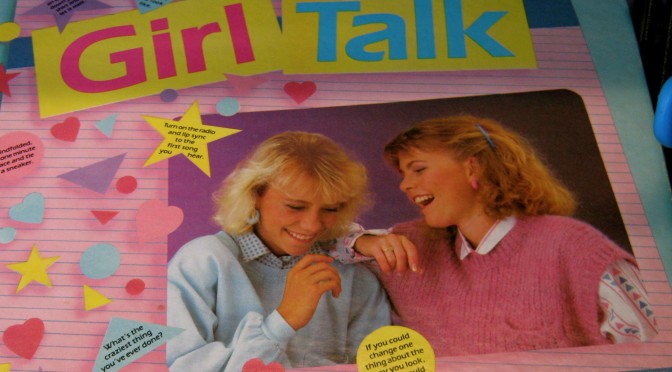

My brother and I, similarly clad in his shabby hand-me-downs, are playing Girl Talk while our single-mother works the graveyard shift at a local truck stop. Girl Talk, first published by Golden in 1988 and then later by Hasbro in 1995, is one of many board games made and marketed at teenage girls in the 80s and 90s. Similar to truth or dare, the game encourages conversations about sleep-overs, boys, shopping, and female bonding. When played by two poor, rural, prepubescent kids, however, it queers the game’s focus on urban, emphasized femininity and requisite conspicuous consumption that accompanies it. This paper argues that although Girl Talk is characteristic of a neoliberal shift in social consciousness that took a new interest in the formation of female subjectivities and the propagation of a exclusive, ideal version of girlhood, it can also be used to subvert these tropes through the queering act of radical play.

First, how do games cultivate and inculcate gender difference? For a board game to cultivate gender difference between its players, it must differentiate and typify the characteristics of masculinity and femininity as opposite yet complementary. These practices focus on natural differences between men and women, “weaving a structure of symbol and interpretation around them, and often vastly exaggerating or distorting them.” The emphasis in this symbolic structure on femininity relies on the subordination of women to men and their compliance to patriarchal standards of beauty and domesticity. Heterosexuality is paramount to the maintenance of these practices.

In Girl Talk, heterosexuality underscores the entire game. Possible truth/dare challenges include “name a boy you’d like to date,” “describe the perfect boy,” and “if a boy you didn’t like asked you out, what would you do?” The explicit addressee of these challenges is female as the game’s instructions show: “Let the girl with the longest hair start first. Or, the most beautiful, the smartest, the youngest.” The importance of physical appearance is constantly reinforced throughout the game. In fact, as the anecdotal introduction revealed, the penalty for failure to complete one of the challenges is to wear a zit sticker for the duration of the game. The accompanying materials read “Put that on my face?! Yuck!” What could be worse than this visible imperfection?

While the game depends on heterosexual motivation, it also involves deep homosocial bonding. Players are challenged to braid each other’s hair, reveal best and worst characteristics of their friends, and tickle each other. While some of these tasks blur the line between the homosocial and the homoerotic, the normalization of this contact as natural feminine behavior continually offsets the threat of homosexual attraction. The discourse of emphasized femininity renders queerness impossible for young females.

Player values are also adjusted to the typical values of patriarchal, heteronormative sociality. By completing the truth-or-dare challenges, for example, players receive points. When a player reaches 15 points, she is allowed to choose a Fortune Card from one of four categories: Marriage, Children, Career, and Special Moments. These cards are intended to be a fun reward for the winning player. Whoever manages to first collect four cards, one from each category, is allowed to read her future in the cards. In fact, the winning girl is encouraged to add to this fantasy by filling in blanks that are left in the Fortune Cards. For example, one card reveals “a pushover for athletes, you fall for (school jock) who will propose 10 years from now.” There is not a single Fortune Card from the “Marriage” category that does not reveal that the winner will marry a man. Similarly, every single card in the “Children” category predicts that the winner will become a mother. While some cards speculate at the number of children the lucky winner will be responsible for, other cards specifically discuss physical traits and gender “after three sons you eventually succeed in having a girl you will name (girl’s name).” Given the limited categories of the cards and narrow range of possibilities within each category, it is clear that the ideal future is constituted be a few key aspects, namely the establishment of a nuclear family and maintenance of hetero-patriarchy. This alleged choice between marriage, children, career, and special moments reflects the rhetoric of neoliberal empowerment, which invariably conflates identity with the ability to choose between products, people, and corporations.

Girl Talk is the socio-political product of a discourse around female empowerment that characterized the mid-1980s. Following the perceived relative success of feminism’s second wave, women entered the workforce in record numbers. The resulting challenge of reconciling career with familial obligations became a pressing and topical issue. Girl Talk reconciled this problematic by promising a natural balance between hetero-domesticity and the workplace through its “career” cards. In fact, a career is ostensibly a good place to find a husband. One card reads, “after three weeks on your first job as a (profession), you’ll meet the man that you will eventually marry.” Yet family does not necessitate the abandonment of career aspirations. One card reassures the winner “you will have children early in life followed by a successful career in (state).” In Girl Talk, girls are reassured that they will have simultaneous access to both the workplace and the domestic space. The career paths available in the game reflect the importance of physical beauty. Over half of the “Career” cards involve acting, modeling, or both. Careers for the players of Girl Talk are simply an extension of their prized feminine attributes: beauty, a malleable personality, and cheerful subservience.

The “Special Moments” cards are skewed to privilege heterosexual romance and the class advantages of conspicuous consumption. In truth, many of these “Special Moments” are so remarkably inane that they only serve as markers of future wealth and the accompanying privilege to indulge in trivial pursuits. Examples include: “You will decorate your future home using your school colors.” and “You will build your dream house in (city).” The casual way in which these grand dreams are offered up as potential futures assumes players of this game are already on this economic track of upward mobility. In Girl Talk, it is only a matter of time before you are picking out drapes and debating a pastel or earth-tone color palette. At first this socio-economic coding seems benign enough, given that this lifestyle is being branded within the context of a light-hearted, children’s game. But some of the game’s implications appear far more sinister when considered in a critical context. One “Special Moments” card promises that “A tall, dark, and handsome policeman will stop you for speeding and give you a ticket, but will make up for it by asking you for a date.” For those in poor, black, and otherwise marginalized communities with an ongoing history of police violence and disproportionate incarceration rates, the prospect that an agent of the state ever offering compensation (especially in the form of consensual romance) is beyond the auspices of fantasy. But Girl Talk is not meant for these girls. This is neither the reality that the game reflects, nor the reality it is selling. Instead, Girl Talk is meant for the unmarked, socially secure bastion of white, middle-class girlhood.

The emergence of Girl Talk in the midst of the feminist ebb of the 80s is symptomatic of the loss of a sense of unity within the feminist movement. Acknowledging the complexity and difference of the female experience meant the reevaluation of the universalizing efforts towards solidarity (key to the moments of the 60s and 70s). Despite the efforts of feminists of colour (such as Audre Lorde and Gloria Anzaldúa) who offered alternative theoretical visions for the moment, the loss of momentum brought about by Reagan era neoliberalism resulted in political stagnation and a return to the status quo of gender inequality. Invisible structures of hetero-patriarachy went unchallenged as commodity capitalism was equated by politicians and business leaders to social progress. Susan Douglas describes this phenomenon as the dual working of embedded feminism and enlightened sexism. Embedded feminism is the mistaken understanding that we are now post-feminist because all the goals of the movement have been met. “Because women are now ‘equal’ and the battle is over and won, we are now free to embrace things we used to see as sexist, including hyper-girliness.” In addition, enlightened sexism “is meant to make patriarchy pleasurable for women.” This modicum of pleasure is achieved through consumptive practices that replace fulfillment with accumulation. Girl Talk typifies both of these ideas. It brands girlhood as both fluffy, pink-hued fun, and also as the launching point for a life of heterosexual submission. By offering players choices between hetero-normative avenues of consumption, the game trains young girls to enjoy this narrow path of possibilities. “The fantasies laid before us, in their various forms, school us in how to forge a perfect and allegedly empowering compromise between feminism and femininity.”

If, then, this game can be seen as a not-so-subtle attempt to instill hetero-patriachal values and reproduce emphasized femininity in a generation of upper-middle class girls, what value remains in critically reflecting on it? The answer is found in experience. While Girl Talk is a product that is branded as a having a very narrow applicable market, its very nature as a game relies on play and meaning-making that exists within the ephemeral confines of the interactive experience. Girl Talk is performed in the moment of its playing and the game is equally constituted by the game’s mechanics/structure and the players. In investigating the subject of this interplay in role-playing games, Arne Schröder stresses that “it is important to take both the narrative and ludological aspects of games into account.” Any understanding of games must approach them as “both cultural products and systems of rules.” People are powerful variables within any system. This perceptive is at the heart of #INeedDiverseGames, an online community of gamers dedicated to promoting games that reflect the diverse demographics and interests of players in lieu of rehashing tired narratives of white, male heroics. Although the hashtag was only created in 2014, the incongruity between player identities and the limited availability of game instituted roles is not a new phenomenon. Queer adaptations are as multiplicitous as the diverse array of people who play games.

The context of play matters. In the case of Girl Talk, the trappings of emphasized femininity were queered when innocently appropriated and re-imagined by a 10 year-old boy, heterosexual boy. While Girl Talk appears to exclude and limit the range of acceptable girlhood, in practice, the game format gives permission to play with gendered practice and symbolically “try on” otherwise prohibited behaviours. The intended subject of a game geared towards inspiring in young girls an inclination to define themselves through consumption does not account for all discontinuities that other player positionalities may provide. In parallel research, it has been revealed that although some games have sought to produce the hegemonically masculine subject, they have failed to account for difference. In their analysis of militaristic video games as technology for preparing civilians for war, Dyer-Witheford and de Peuter remark that “Media audiences are comprised of subjectivities that are multiplicitous, assembled in manifold and contradictory social formations. Positions inscribed in games…are not necessarily replicated by players.” Interpretation is dependent on context and the mischievous and otherwise ideologically truant players can alter the message.

As children, my brother and I did not play this game ironically, nor were we intending to make a subversive statement about the indoctrination of gender in children. We were not protesting against the economic exclusivity of the narratives of success, nor the normalization of the nuclear family. Despite this, we did shape the game to fit our resources and desires. We did re-word dares, expand the rules, and blur the limits of gendered behaviour. He braided my hair and I called female friends to confess crushes. In the context of a game, all things became permissible and possible. While a normative and exclusive version of femininity is packaged within Girl Talk, the free play offered by its platform as a game allowed players to queer the bounds of gender and sexuality that form the unspoken basis of the game. While other radical gamers (like those affiliated with #INeedDiverseGames) are now improvising with the parameters of classic games and creating new games which challenge the limits of normativity, I believe that the manner in which my playing experience anecdotally queers the neoliberal project of Girl Talk is relevant because it challenges the notion that radical play is a newly emergent concept. In fact, the very nature of a board game’s materiality begs for players to bend, break, and blur the rules. Although the game’s packaging states that this is “a game designed just for you”, for two wayward, country kids, Girl Talk was a game re-designed just by us.

–

Featured image “like, omg” by Cristina @Flickr CC BY-NC-SA.

–

Amber Muller is a wayward Canuck. After graduating from the University of Alberta with a BA (Honors) in Drama she played at theatre making before moving to Europe to pursue a double Masters in International Performance Research at the University of Amsterdam and the University of Warwick. Currently engaged in PhD in Performance Studies, Amber is also working towards designated emphases in Feminist Theory and Research and Critical Theory. Her research focus lies at the intersection of performance and sexuality with a special interest in sexual economies, erotic capital, collisions of praxis in pop culture feminism, gender politics, creative protest, and embodied resistance. She enjoys popular media, mixing “high” theory with “low” culture, troubling currents of power, and being a feminist killjoy.