Introduction

Historical simulation and games-based learning have demonstrated over the last two decades that they are mediums that support learning about the peoples of the past. In ways, they are pedagogical tools that are relatively more effective in cognitive and affective gains in students when compared to traditional and more passive mediums such as books, film and TV.

But there is a dearth of simulations and games that deal with recent and harrowing periods of history such as the Troubles of Northern Ireland. Often it is the negative and less serious connotations attached to the term ‘game’ that suggests that this medium is inappropriate for serious and sympathetic study. Furthermore, the field of conflict studies often demonstrates a reluctance to engage with controversial periods of history—particularly those in which violence was directed at civilian populations rather than confined to conventional battlefields.

However, The Troubles (2026) is a card-driven (CDG) tabletop simulation that deals with one of the 20th century’s “previously overlooked histories”—Northern Ireland. All research, design and development were undertaken by the author of this paper and it is intended for commercial publication and international distribution by Compass Games LLC in the U.S.

Boardgames “are by their nature communal and collaborative in nature, with all participants sitting around a table together on an equal footing.” Through realistic collaborative and competitive play, where player decisions, actions, and outcomes that closely mirror the logic, constraints, and consequences of real-world events or behavior that are historically grounded, The Troubles immerses each player as one of six key factions in the “personal feelings and emotions connected with a complex understanding of history.” It provides many emergent historical and ahistorical narratives as players participate politically, militarily, or paramilitarily in the national and international affairs of Northern Ireland between 1964 and 1998. In this way, The Troubles is an essential pedagogical tool in Historical Memory Education, which is used to study recent, contested and competing histories.

Furthermore, simulations—or the recently introduced concept historically-structured boardgames—like The Troubles are like museums in that these powerful and affective narratives are produced by artefacts within a specific historical context. This paper examines how the physical elements of informal learning sources like games and museums contribute to empathetic simulations of violent conflict. It focuses on the components of The Troubles and how they interact with players to represent the experiences of those affected by the Northern Ireland conflict.

Historical Context: Ireland’s Conflicted Past and Present

Ireland had been under English rule since 1604. The Protestant British and Catholic Irish divide fueled centuries of conflict, worsened by land seizures from Catholics to Protestant landowners. British efforts to control Ireland saw greater success in the Protestant-majority north (Ulster), while rebellion persisted in the south. The Great Famine (1845–1852) was a catastrophic period of mass starvation, disease, and emigration in Ireland, caused primarily by potato crop failures due to blight and exacerbated by British government policies. This event only drove greater demands for Irish self-rule.

The Home Rule movement sought Irish independence, but Northern Protestants opposed it, identifying as British. Failed Home Rule Bills (1886, 1893, and 1912) escalated tensions, leading to the formation of paramilitary groups: the pro-Union Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the nationalist Irish Volunteers. The Easter Rising, a 1916 armed insurrection in Dublin by Irish republicans aiming to end British rule and establish an independent Irish Republic failed, but the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) and electoral success for Sinn Fein, an Irish political party that advocates for Irish reunification and traditionally supports a nationalist and republican perspective, led to the partition of Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act (1920). The Irish Free State was created in 1921, while Northern Ireland remained in the UK, with contemporaneous governmental reports such as The Cameron Report (1969) and The Scarman Report (1972) acknowledging a system of gerrymandering that favored Protestants. Catholics in Northern Ireland faced socio-economic discrimination from the majority Unionist government.

Civil rights efforts in the 1960s sought reforms, but Unionist resistance and paramilitary violence reignited tensions. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) re-emerged, leading to the Troubles (1964–1998), a violent sectarian conflict that claimed 3,500 lives and caused widespread structural harm: trauma-inducing violence that would limit the population’s quality of life and therefore decreasing their life expectancy.

Educational Context: Teaching the Troubles

In 1998 the Good Friday Agreement was a political deal that established a power-sharing government drawn from both the Nationalist and Unionist political parties. Acknowledging both British and Irish identities, it aimed to end decades of conflict known as the Troubles, and since this historic year there have been formal and informal educational attempts at reconciling the competing narratives associated with the Troubles. Opening up old wounds and perpetuating the division and hatred of the other community is a key concern of societies which are transitioning from historical violence.

Education is only one facet in strategies aimed at continued engagement and discourse about ongoing “sectarian tensions and possible reconciliation.” Teaching the Troubles presents a unique challenge for educators as they must navigate deeply personal and polarized perspectives. Already with the demands of curriculum and educational policy, they have to ensure that student’s well-being is met and that community relations are not imperiled by undertaking sensitive and discomforting pedagogical practices. Teachers must be cognizant of their own biases whilst attempting to maintain neutrality and sensitivity.

Personal and collective memory plays a crucial role in how individuals understand and engage with the history of the Troubles. This history is recent, with many families still dealing with the loss or injuries of the Troubles. Personal memory is constituted and deeply ingrained through the combination of familial testimony and community allegiances. Educators must synthesize this with personal, collective and accepted history.

Incorporating diverse storytelling methods—literature, film, oral history, and digital media—allows students to explore multiple memories and perspectives and develop both cognitive and affective empathy. No single approach should be used: it should be interdisciplinary and diverse. Moreover, the power of narrative—telling or writing stories—is certainly a recurring theme at the heart of previous research into the Troubles and used as a way of allowing participants to accommodate or even consider alternative perspectives.

An effective approach to teaching the Troubles requires balancing emotional engagement with critical thinking, fostering an understanding of both historical complexity and the shared human cost of conflict. History teaching of such topics must engage feeling and thinking, inviting us “to care with, and about, people in the past, to be concerned with what happened to them and how they experienced their lives” and the use of narrative as a medium to do so focuses on the “common humanity” that exists across the divide. Educators and students alike must explore the realities of what was done, and what the true human cost was.

What these authors agree on is the polarization of opinions on the historical period between 1969 and 1998. However, critical engagement is essential in order that the nuances that exist between these stratified opinions may be revealed as they are often deeply personal stories of actual lived experiences that must be valued and that we “make space for the messiness of people’s lived experience.”

Theoretical Framework

Historical Memory Education (HME)

The latter half of the 20th Century is replete with conflicts spanning the globe: the Middle East, Asia, Latin America, Europe, and Asia—it seems that no continent has been untouched, each attempting to heal its scars through citizenship education. Many remain unknown, forgotten or even excluded through what is called the ‘null curriculum’, referring to knowledge and perspectives systematically omitted from formal education.

Regardless of where human rights abuses, war crimes, or civilian killings have occurred—whether by terrorists or state actors—certain common approaches emerge. At the same time, there are numerous barriers to effectively teaching or simulating these events. Research has identified a need for approaching what are often bitterly divisive, polarizing, and abhorrent histories.

Historical Memory Education (HME) is a branch of peace education. Peace education promotes knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that help people prevent conflict, resolve disputes non-violently, and build a culture of peace. HME focuses on designing and reviewing educational experiences related to healing the wounds of recent violent conflicts and authoritarian regimes. It aims to support victims’ rights to truth and to ensure that such violence is not repeated. Education plays a key role in achieving these goals. It emphasizes the importance of domain knowledge and the narratives from personal and collective engagement with the historical focus of study.

Furthermore, more recent conflicts are considered pertinent areas of study, as is the focus on the human cost to historical expediency—the way that players make decisions based on what would have been practical, strategic, or necessary in a specific historical context, even if those choices conflict with our values or ethics. This foregrounds the tension between doing what is morally right and what is historically realistic or advantageous. This aids players to understand the difficult compromises faced by people in the past.

Participants are not simply learning historical facts: they are afforded the opportunity to interrogate and undertake an interpretative approach to history: key characteristics are participant agency and the ability to react and reflect, collectively, on the consequences and results of an event. From this agency comes an increased sense of historical identity, the participants’ adoption (temporarily) or understanding of the beliefs, values, perspectives, and social roles of people from the past, helping players connect cognitively and affectively with events, encouraging deeper empathy and insight into the complexities of the past.

Controversial historical events and accounts are difficult, often taboo: they cause others to relive the trauma. There are many competing narrative perspectives, which may be maintained by some parties to manipulate what was done in the name of some ideology as “glorious deeds of the past.” But there is a need for honesty and reciprocity in sharing responsibility, whilst relaxing intellectual control that stifles agency and meritocracy.

There are important personal and societal benefits to active political participation and dialogue supported by the socially constructed and often conflicting discourse found in social education programs. Narrative-based simulations and games, where players take on roles within stories involving consequences and dilemmas, contribute to this process. These experiences highlight the human cost of conflict, allowing participants to “visualize the tragedy…the numbers of people affected, the different points of view…the complexity of these [particular] kinds of historical events.”

It is our duty that the horrors are not forgotten or diminished and that the perpetrators are brought to account, morally and legally: “irrespective of where the victimization originated the function of the victim who educates is to share their experience and the injustice that they suffered.” The key aim is that by critically engaging with historical conflict “if we all remember, it will not happen again”; and that “to confront imaginatively the harsh reality of suffering and death, political differences are perceived as being very secondary indeed.”

HME outlines the educational and human benefits derived from engaging with “all parties to the past conflict,” no matter how undesirable and distasteful this may seem to the various participants involved in what are often profoundly violent conflicts, as their “goals and circumstances” act as moral agents in the journey of fostering moral agency; diverse narratives do not, as previously believed, exist in mutual exclusivity.

Historical Empathy

This work considers the use of history in simulation and play. Historical knowledge is gained from a study of people and events from the past with an understanding of the context in which events occurred, so that such an undertaking informs those embarking on such inquiries develops as individuals and as part of society—“it changes what [students] see in the world and how they see it.” The study of history should be rigorous and critical, adding to the knowledge of the individual studying it. History aspires to an evidence-informed account of the past where learning immerses students in “a collective inquiry into knowledge, and coming to a deeper understanding through interactive questioning, dialogue, and continuing improvement of ideas.”

If it allows students of its discipline to inhabit the world in which they are placed, then simulated histories allow players to be better informed in challenging, probing and understanding the characters that they meet, and assume the identity of. To do so, we must develop historical empathy by inhabiting the individuals and their perspectives of the socio-cultural structures that formed their opinions and shaped their actions within invariably complex historical situations.

Historical empathy is important because it gives us a richer understanding of history then and its consequential impact on others as well as our own lives. We achieve a dual perspective through empathy with historical actors because we do not bring our present-day understandings into their world. We recreate the social-economic structures of their time of action, and using play allows students of history to be analyzed as “geopolitical texts” which constitute part of a society’s “everyday life.” This creates a “heuristic cycle” between the cognitive and affective domains of the individual imaginatively and critically exploring the past.

Cognitively, the more knowledge of the subject area, the more coherent and grounded the participant shall be as their imaginative constructions require as much knowledge and detail for them to be realistic and sustainable. Therefore, this scaffolded knowledge allows participants to connect affectively with the social world that they are attempting to inhabit. Ways of acting within this period of history are derived from the knowledge and context of this world and affording wider player agency in the pursuit of authenticity. This knowledge of the imagined world depends also on the degree of familiarity in the varied personal histories of the players themselves and is augmented by the associated historical supplement that is included with The Troubles.

In the development of board games on recent and contested histories like the Troubles in Northern Ireland, it is essential to consider the ethical implications of representing sensitive historical events in a game format. Ethical considerations should encompass issues of accuracy, respect for the lived experiences of those involved, potential biases, and the impact on players’ perceptions of historical events. Balancing historical accuracy with sensitivity and inclusivity is crucial in creating a game that fosters understanding and empathy without trivializing or sensationalizing the complexities of the conflict.

Historical Simulations, Games & Study

One approach to studying history is through analog board games and digital simulations and games. Pedagogical in goal, historical simulations model real-world systems of the past and provide an opportunity to examine the behaviors of processes and people involved. Similarly, games attempt to provide an immersive representation of a period from the past, enabling participants to ‘play’ in that re-constructed world. Both terms are used often used interchangeably, but the label ‘game’ carries connotations of fun, enjoyment and that it treats its subject matter in a light and fanciful manner, often at a higher level of abstraction than a simulation. Often the phrases “serious game” or “historically structured board game” are used in acknowledgement of this contention and wish to highlight that there is a serious pedagogical aim.

There is a plethora of historical wargames and other genres of games that allow players to immerse themselves in historical moments and play within their historical ‘surroundings’, for example, Paths of Glory (1999), We the People (1993), This War of Mine (2014). Many historical games do not just impart historical facts, they encourage critical reimagining and interpretations of the past. But history itself is a constructed and often contested discourse, shaped by power, perspective, and selective memory. Historical perspective is therefore inherently contentious, polyvocal, and frequently deemed controversial, with studies revealing “deeply hegemonic interpretations of and perspectives on the past.” Rodino et al refer to this as the development, through commission or omission, of a “null curriculum” while Ondek and Laurence call it a “rhetoric of silence.” Ostensibly the existence of such a curriculum may be a sign that a society or nation is wishing to leave behind a violent past as a sign of progress and therefore its education system does not include these important events and topics. However, omitting the truths and memories of the past fails to provide the necessary justice for its victims, and it also risks preventing future generations of a society from making critically informed decisions about its past.

This dearth of instructional implementation of curricula in education that approaches and challenges difficult histories is matched by the reluctance to design and publish games or simulations centered on controversial periods or aspects of history.

Narrative-Based Simulations

As a response to this scarcity, narrative-based simulations emerge as a compelling approach, offering a means to navigate sensitive histories by structuring complex content through the accessible and humanizing lens of storytelling.

Our lives depend upon communication, narratives are imperative to how we see the world. It is through narrative that we access history: events “are the basic building blocks of narrative.” Historically, narratives are one method with which we “humanize complex information.”

Schell argues that “there are four fundamental elements that constitute a game namely: aesthetics, mechanics, story, and technology—the ‘elemental tetrad’ game design framework.” The first three are of priority with traditional physical table-top games and simulations. The idea of aesthetics is extended beyond the physical attributes of dimensions and color associated with the map boards and components of many simulations, as Hunicke et al. look at the affective effects upon the player(s): color and symbology continue to define the ingrained identities of the historical actors, cultures, and ideologies, and other parties involved in the game’s narrative. In effective game and simulation design, story is deemed “the Golden Rule,” and mechanics—the rules, the actions of each player and their interactions—will lead to a more immersive, compelling and realistic narrative experience if they match the theme or historical period being represented.

The story relates to the real-world events that provide both the accepted (and contested) narratives that are being simulated; the emergent discourse that develops as players compete and collaborate to succeed augment or provide alternatives to existing stories.

The narrative design and the mechanics deliver the “historical context” that is then juxtaposed with the “historical action” and collective narrative experience of the players. Both the presence and the agency afforded any factions are integral to the verisimilitude of the narrative, the authentic characterization of the story being modelled, generating more immersion, engagement, and motivation; pedagogically, the inclusion of controversial viewpoints and actions “supports the comprehension of other people’s goals and circumstances as moral agents” which are integral to our development of “moral agency.”

Using the lens of HME, The Troubles tabletop simulation provides the “expert knowledge” of the authored narrative present in the game’s design, alongside the co-constructed, emergent personal and collective narratives of players in “a societal context…cultural, sub-cultural, political, economic, historical.” This adoption of an empathetic perspective of the historical actor “when people narrate morally relevant experiences, they engage in constructing an account of actions and consequences that also includes beliefs, desires and emotions”they are narrating through the faction and themselves.

Museums and Simulations

Museums are important and contextualized places of informal learning about the past. They provide opportunities for visitors to create “emotion-laden memories” from accounts relating to their visits, which are self-motivated and are supported from non-linear approaches to exhibits.

It is widely evidenced that narratives are powerful tools in knowledge learning, and retention especially when such learning is situated and given a context. Moreover, as with all communication, museum learning is socially mediated at both individual and group levels with meaning-making being shared and providing a myriad of viewpoints. Museums provide human beings with opportunities to co-create distributed narratives during and after their visit: the language of discourse is a powerful function of memory and knowledge as visitors reflect individually or mediate with others on what they saw, touched, smelled; the captions and labels that they read; the audio descriptions or ‘tours’ that were personally presented to them or delivered via a headset.

Since museums can move people and evoke strong emotional responses, so should tabletop games and simulations that deal with controversial historical events, developing both the cognitive and empathetic traits of its human players. To conflict studies and Historical Memory Education (HME), museums can therefore offer opportunities for formal and informal learning about past atrocities and violations of human rights. In this way, The Troubles acts in a similar way as a museum experience.

Museums offer their visitors the opportunity to view, touch, and even manipulate objects. The tactile nature of these elements allows players to engage more deeply with the game world, fostering a sense of presence and connection. This cognitive engagement is further enhanced by the need to mentally map the game’s physical space and anticipate the consequences of each move.

Whereas traditional narratives—textbooks, documentaries, films—are linear in their exposition, visitors to museums and participants in a game often choose their own path(s); the overall narrative may appear fractured and episodic, but these visitors have a greater sense of control and agency in their participation in an “ever-changing social, cultural and physical world” to mentally organize and collate their visits as stories. The physical act of placing a cube or moving a counter can serve as a focal point for conversation and shared decision-making.

However, museums are subject to financing their operations within the non-profit sector as they compete against other institutions in garnering public interest and their valuable time. There are also limitations to how much public expenditure is awarded to museums due to the predilections of changing governments.

Museums are increasingly challenged by the spread of virtual experiences, virtual collections which are often privately funded, situated, and bound to a geographical location with constraints on volume of visitors, opening times, and other restrictions to the access of its valuable resources. Within this static location, a singular pathway and thus ‘narrative route’ may be all that is accessible once and once only. The use of games and simulations are an alternative path to introduce patrons of this genre to other aspects of history, which may be appealing because of the growth in both the analog and digital mediums, which in recent decades have led to:

developments within the historical profession and the emergence of a new set of representational possibilities [that] are countless and the opportunities for obsessively detailed gaming scenarios and speculative intervention endless.

Such historical ‘exhibitions’ are brought to them; historical games and simulations are not a physical (and perhaps time-limited) event to which they must travel.

Case Study: The Troubles

Overview

The Northern Ireland conflict, known as the Troubles, spanned the years from 1969 to 1998 and remains a deeply complex and contentious historical event. The Troubles board game is the first tabletop simulation to engage with this recent conflict. And some may say too recent, as many of those who were affected by it are still alive, and the necessary time for a proper objectivity of perspective has not elapsed. The game explores themes of historical oppression and the representation of marginalized identities against a backdrop of four decades of violence that resulted in the direct loss of over three thousand lives.

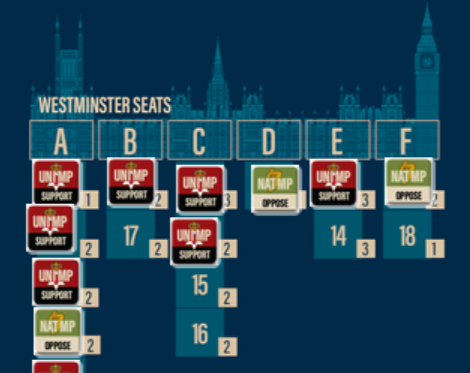

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

At the time of writing, it has been assigned an age rating of 16+ on Board Game Geek, which concurs with discussions with Compass Games LLC. This decision has been made with a view to it being used in higher educational contexts (i.e. beyond school) based on its complexity and the events it depicts.

Designed as a historically structured board game, The Troubles conveys its narrative, including its mechanics, through a design informed by historical sources. The game features a chronologically adaptive map, period-appropriate faction actions, and a 260-card historical Narrative Deck, which can be played either chronologically or in an alternative order. This deck provides key events from the conflict, offering both historical and counterfactual play.

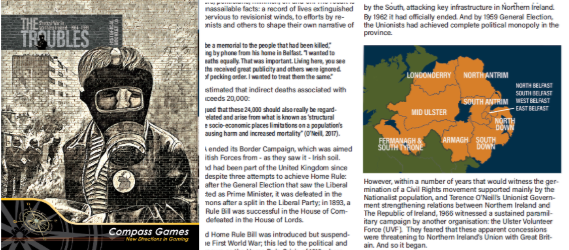

Additionally, there is a 72-page rulebook as well as a 52-page historical supplement that gives players historical context about the conflict, background information on each of the six factions, and design notes and narrative summaries for each of the 260 narrative cards.

Source: The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

Both the rulebook and supplement provide extensive bibliographies that list the source materials and other educational media that was used in the formation of the entire design and which may be used by players and pedagogists to support further study. To this domain knowledge players bring their prior knowledge, presuppositions, and biases to the game, engaging in historical meaning-making through immersion in the conflict’s social complexity—a process required in Historical Model Empathy (HME).

Game Overview: The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland 1964-1998

The Troubles is a two-to-six player, asymmetric card-driven game (CDG) designed to simulate the political and military struggles of Northern Ireland.

The main playing area depicts a map of Northern Ireland as well as other status tables:

- the score track, which holds status markers for victory conditions;

- the situation area, which tracks things such as the UK Terror Threat, IRA/LOY and NAT/LOY support;

- the Dublin track, which models the Republic of Ireland’s stance towards the IRA;

- the turn sequence area;

- the Peace Sequence of Play area (an in-game mechanic for simulating the machinations of the LOY or IRA factions embarking on a road to peace;

- place holders for the narrative cards—current card and remaining deck;

- the international area, where arms deals are facilitated;

- the Westminster area that displays an overview of the 12 (increasing to 18 by 1997) county seats;

- the funds and resources area to track each faction’s currency that facilitates actions.

There is also smaller separate map depicts the city of Belfast (see Figure 2). The main map is bordered by six smaller player boards, one for each faction; each board contains a mix of cardboard counters and either cubes or octagons of a variety of colors. For example (see Figure 3) the LOY faction has 40 volunteers and 10 bases available for deployment. It has the ability to undertake use the car bomb mechanic and relocate volunteers and bases in Great Britain (indicated by the Carbomb and Mainland development counters). It has established 2 Arms Deals and accrued 3 Arms Dumps.

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

Factions and Objectives

Each player assumes the role of one of six factions attempting to influence Northern Irish affairs through political, military, and paramilitary means. The game blends area control with resource management, as players contest control over Westminster parliamentary seats in Northern Ireland, the presence of British Troops on Irish soil, and preservation of the union between Northern Ireland and Great Britain.

The six playable factions are:

- British Forces (BF)—Includes the British Army and the Ulster Defense Regiment (UDR)

- Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC)—The Northern Irish security force and the Ulster Special Constabulary (“B Specials”)

- Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA)—Irish republican paramilitary organization

- Loyalist Paramilitaries (LOY)—Various loyalist militant groups

- Nationalist (NAT) Political Parties—Representing the political wing of the nationalist movement

- Unionist (UNI) Political Parties—Representing the unionist political agenda

Game Mechanics and Components

Each faction has access to a distinct set of resources, funds, and abilities that influence both their strategic and tactical decisions.

Core Components

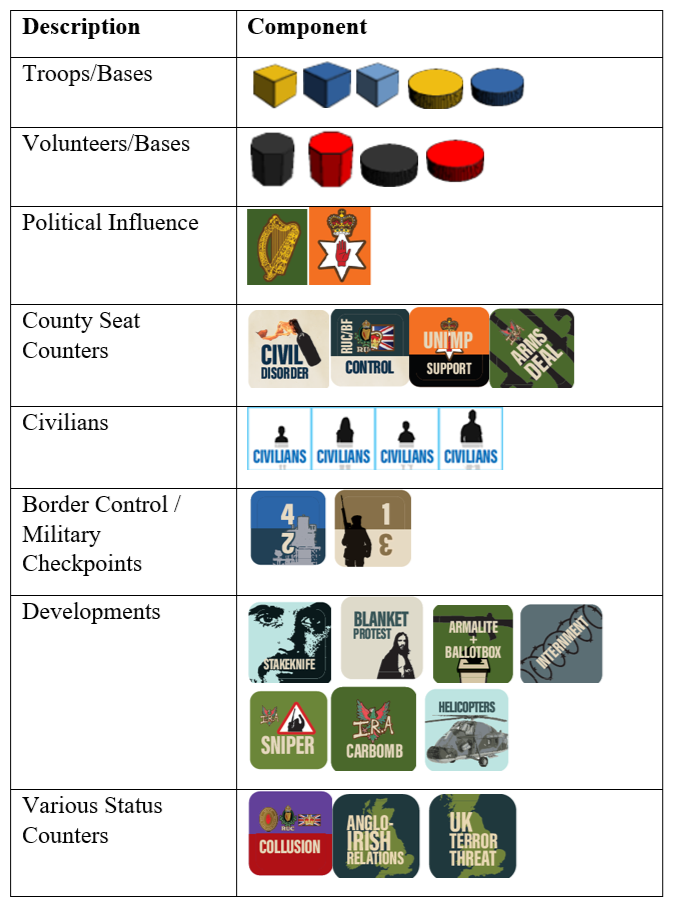

The game includes:

- Military/paramilitary units (troops, volunteers, bases, special units)

- Political Influence counters (representation of each faction’s sway over Northern Irish politics)

- County Seat counters (used to determine political and martial control over electoral regions)

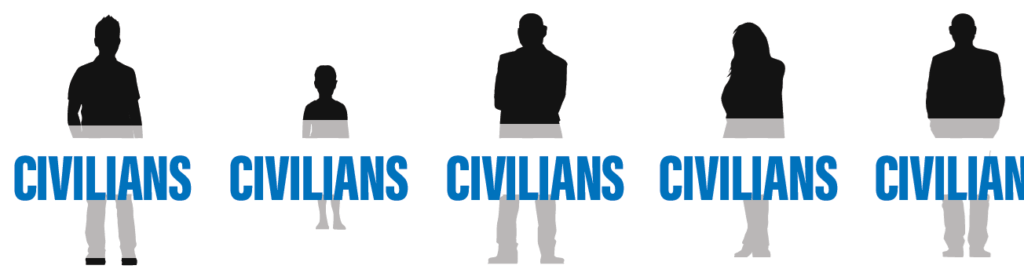

- Civilians & Status counters (tracking civilian imprisonments, and county and faction states)

- Border Control & Military Checkpoints counters (representing key security measures within Northern Ireland, and the border between the Republic of Ireland)

- Development counters (technological and intelligence advancements that evolve over time)

- Narrative cards (a deck of 260 detailed historical cards representing key events)

Source: The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

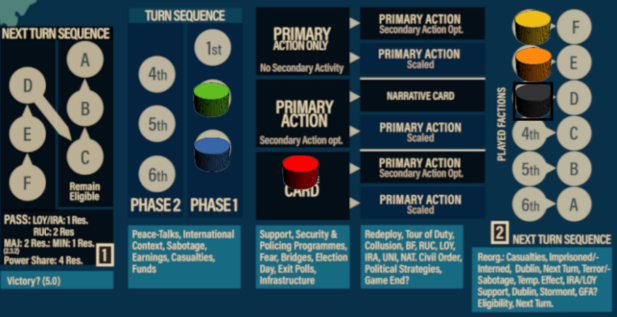

Turn Structure and Actions

Play is executed across two phases. In each phase, three factions assume a turn position that not only grants them a turn but also facilitates their ability to affect the preceding faction’s opportunities.

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

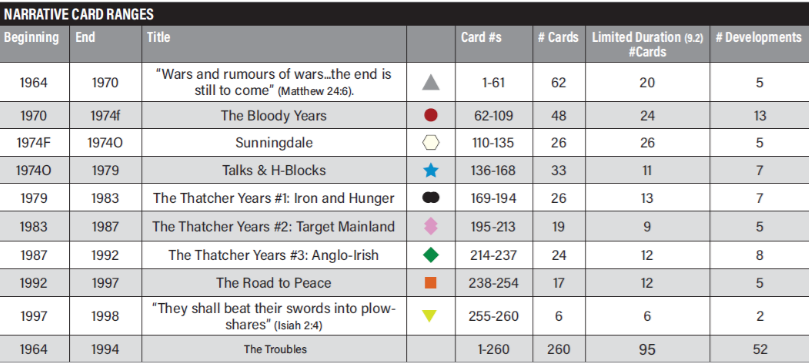

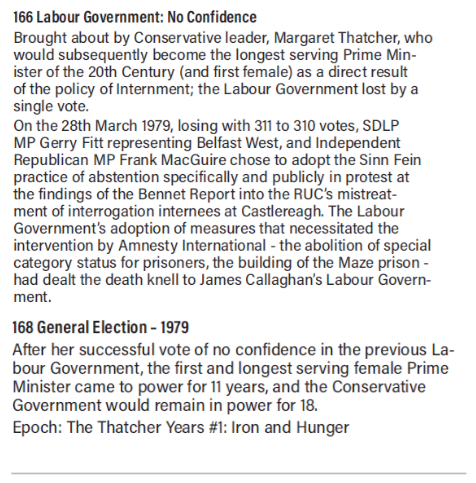

Each faction may use their Primary and Secondary Actions, abilities analogous to its real-world counterpart (e.g. Arrest, Attack (Bomb), Canvass, Relocate). Or they may choose to play one of the narrative cards for that particular Scenario (see Figure 5): the 260 narrative cards are divided into nine key epochs in Northern Ireland’s recent history (see also Table 2):

- 1964 – 1970: “Wars and rumours of wars…the end is still to come” (Matthew24:6)

- 1970 – 1974(F): The Bloody Years

- 1974 (F) – 1974 (O): Sunningdale

- 1974 (O) – 1979: Talks & H-Blocks

- 1979 – 1983: The Thatcher Years #1: Iron and Hunger

- 1983 – 1987: The Thatcher Years #2: Target Mainland

- 1987 – 1992: The Thatcher Years #3: Iron and Hunger

- 1992 – 1997: The Road to Peace

- 1997 – 1998: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares” (Isiah, 2:4)

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

International & Political Dimensions

The game’s mechanics encompass the international dimensions of this recent conflict, foregrounding the USA, Great Britain and European’s role in supporting the terrorists’ arms networks. It also depicts the complex relationship that existed between the Republic of Ireland, Britain, and Northern Ireland.

Developments, a feature that mirrors the increasing technological and intelligence-led advancements on both sides, are also featured and, like the Victory Conditions for factions, they evolve as play progresses. Victory Conditions encompass shifting strands of collaboration and competition. For example, when the Power Sharing Development is enabled, the opposing political factions, the UNI and NAT, may then opt to share governance of Northern Ireland and therefore work together, assisted by the security forces of the BF and RUC, to remove the paramilitary threats posed by the IRA and LOY, whilst simultaneously reducing the number of deployed BF troops. Alternatively, when the Collusion Development is enabled, the BF and RUC forces may enlist the help of the Loyalist paramilitary faction (LOY) in targeting the IRA, maintaining the majority rule of the UNI political faction. Both situations actually occurred during the time of the Troubles, with the British Government still facing a growing body of evidence that indicates that throughout the decades-long conflict in Northern Ireland, various British military, police, and security agencies conducted a covert ‘dirty war,’ often disregarding human rights and legal standards in the pursuit of counter-insurgency operations.

Narrativizing Tabletop Simulations as Museum Experiences

As spaces of exploration contextualized by the objects, texts, and iconography they contain, historical simulations and games resemble museums. A ruleset and a manifest of components dictate the initial setup of a play session of many simulations and games. They then become living storied histories as players interact and curate the components during sessions of play. Using the lens of HME, The Troubles provides the “expert knowledge” of the authored narrative present in the game’s design, alongside the co-constructed, emergent personal and collective narratives of players in “a societal context…cultural, sub-cultural, political, economic, historical.” This adoption of an empathetic perspective toward the historical actor enables players to “reinforce their understanding of the complexity of individuals, situations, and judgments” while narrating through both the faction and themselves.

Leinhardt and Crowley propose four characteristics that make museum objects suitable narrative “nodes” for connoting cognitive and affective responses in people, as well as acting as anchors in the emergent narrative webs that are formed during and after a visit:

- Resolution and density of information;

- Scale;

- Authenticity;

- Value.

Each of these attributes are evident in The Troubles.

Resolution and Density of Information

As play progresses, general elections, arms deals, murders, negotiations, arrests, and peace deals are fresh in the memories of those affected, as concrete as the towns, highways, and ferry routes that still exist on this map, and upon which cardboard and wooden components are placed, moved, and removed.

Resolution and density of information relates to the physicality, and the visceral cognitive and emotional response that the museum object imparts to the viewer or beholder. Objects have “a fixed form and a definite factual history”, which are the ‘realistic constraints’ that a viewer must have when attempting to view and interpret it.

Transferring this first feature of museum to simulations such as The Troubles relates to the literal information as well as the connotative effects that the wooden and cardboard components, colors, symbols, place names, and historical events construct from the period known as the Troubles in the imagination of the players, emphasizing individual experience and daily life over traditional historical events and structures.

Already well-established in the games industry for political and wargame-themed titles such as 1960: The Making of a President (2007), Labyrinth (2010), and Red Flag Over Paris (2021), Domhnall Hegarty produced all artwork for The Troubles, stating:

I went with a color scheme that most reflects my memories of the troubles. Late Seventies through mid-Eighties, the time when I was least consciously aware that there was anything out of the norm with the state of things.

During play, there is something visceral, veridical, in holding between one’s finger and thumb a black, 15mm by 8mm hexagon, embossed on one end with a golden phoenix and knowing that this represents an Active Service Unit (ASU) of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA); the sound it makes contact with the paper playing board and slides slowly across one of the major roadways, perhaps at midnight. The hexagon, standing tall at 15mm literally and metaphorically casts a shadow on the town at which it stops, the black representative of the berets often seen in propaganda footage as a handful of Republicans practice maneuvers in front of the VHS camera, amongst the heather and scrub of County Armagh; the phoenix, an important symbol of rebirth, that of the formation of the Provisional IRA from the ashes of the existing IRA. The non-embossed black end connoting that this ‘sleeper cell’ carries potential, an innumerable number of (mainly) young men bound together through the Armalite. The act of flipping it indicating the power afforded the player: to carry out an attack on the foreign boots of the British Army; to avenge recent Loyalist atrocities; to facilitate an arms deal; or to deposit an incendiary device in the name of freedom from British imperialism.

A white-backed counter displaying a single word, ‘Civilians,’ and silhouettes of heterogeneous human beings rests in the ‘Casualties’ area at the top of the map (see Figure 8). The lost lives. Innumerable Civilian prisoners and fatalities backgrounded by this atrocity and ignored in the desperation for vengeance or collateral; each side blaming the other.

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

A small tan cube is deployed to Londonderry (highlighted in Figure 9). This 8mm x 8mm tan-colored wooden component represents British Army troops: some seasoned veterans conducting another ‘tour of duty’; among them are some fresh recruits, not yet twenty years-old inside an armored troop carrier. It joins two dark blue Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and 1 light blue Ulster Defense Regiment (UDR) unit; this area is in Civil Disorder due to the Active Service Units (ASUs) of the IRA and LOY, depicted as black and red hexagons.

It comes to rest beside a small, red cylinder—embossed with the Red Hand of Ulster—which denotes that it is a Loyalist (UVF) base. It may represent men in balaclavas in a dusty upper room in West Belfast, tables arrayed with a cache of weapons including hand grenades and small arms (note the Arms Dump counter); it may represent footsteps upon rain-soaked cobblestones of an alleyway, pistols drawn.

Simultaneous to the play between the Security Forces and the paramilitary factions, orange and green counters bearing golden harps and red hand of Ulster images representing the political factions, the Nationalists (NAT) and Unionists (UNI), are added or removed, representing volunteers carrying out canvassing activities, harangued by housewives on doorsteps, vying for political equity amidst the bullets and the bombs, trying to make gains in this marginal seat. Trying to find a political solution to the Troubles, vying for parliamentary representation at Westminster (see Figure 10).

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

This sample scenario is demonstrative of one of the four qualities exemplified by artefacts of tabletop simulations, which are analogous to the ‘reading’ of museum exhibitions; the constellation of nodes is traversed by invisible threads of relation and meaning, which help to create the episodic “basic building blocks of historical narrative.”

Scale

The second characteristic, scale, relates to the physical size of the object in relation to other elements in the ‘exhibit’ or the viewer(s). The size of an object is not only important in conveying its innate function, but also its relationship with other objects and people: how it is interpreted by its literal size and in relation to others.

The maps and components of The Troubles are merely representative of the objects, people or places that they represent; one must mentally transform small pieces of wood and cardboard into human beings, beliefs and material. Looking at these objects collectively there is a real responsibility, real sense of agency and control, as well as choice and consequence. Almost full gnosis is given to the players; a few exceptions facilitate the randomness and chaos of the setting.

Utilizing the terrain—urban and rural—as well as the Nationalist and Unionist communities, the IRA and Loyalist octagons are of a similar scale to the British Forces (BF); this helps to illustrate the power balance this, and many other, insurgency-based conflicts shared. An Active Service Unit (ASU) may lack the intelligence or technological sophistication of the force represented by the small tan cube, yet on the map they are of equitable threat to the British Armed Forces (see Figure 11) when one considers that the power of the Republican and Loyalist paramilitaries was often supported by foreign governments and international organizations.

The smallness of an ASU is paralleled by the physical characteristics, mentally transforming them to realize that they have the power to wreck a Peace Agreement, cause the fall of a government, and wreck so many lives. The vulnerability and powerlessness of civilians forced to provide a ‘safe house’, suffer loss or imprisonment, be extorted financially and emotionally, and failed by a state currently accused of facilitating and colluding.

The entire ‘world’ inhabited by the six factions is confined within a 22” by 34” playing space that depicts the Six Counties of Northern Ireland. It represents 14 thousand square kilometers of urban, open and rural land upon which thousands of lives were lost. It depicts the border between the North and the South of Ireland, which for some represents a scar remnant of hundreds of years of wrestling; for others a fragile, porous division between Home Rule and Unionism. The names on the map: Londonderry (Derry), Belfast, Westminster, Dublin, Enniskillen, Omagh. Small pinpricks on the map; huge reservoirs of hurt, once peaceful communities now forever grieving.

This relatively small footprint of land demonstrates how internationally relevant the United Kingdom and Ireland were and continue to be post-Brexit. Much of the terror was domestic, but there was international culpability, too. The long reach of the invisible tendrils of the illegal arms networks spanned Europe, the Middle East and the USA, and through which funds and materiel pulsed. And so too would the Peace Agreement require European and International co-operation and resolution.

Authenticity

Authenticity refers to the object’s uniqueness to the historical event(s), its provenance, creating a bridge in time between recipient and producer or original owner. The authenticity of museum pieces relates to their specificity as individual cultural entities.

In The Troubles, play begins in accordance with a setup Scenario that commences immediately following the resolution of a U.K. General Election. Players are directed in the positioning of all playing pieces, trackers, and the complement of cards to be used as the narrative card deck. The location and volume of British Forces and Royal Ulster Constabulary bases, position of military checkpoints, border crossings, the political temperature between Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland, electoral ratios and Westminster Seat distribution are all replicated using military records and electoral data. It is perhaps unsurprising that paramilitary base locations and related information regarding paramilitary forces are less specific.

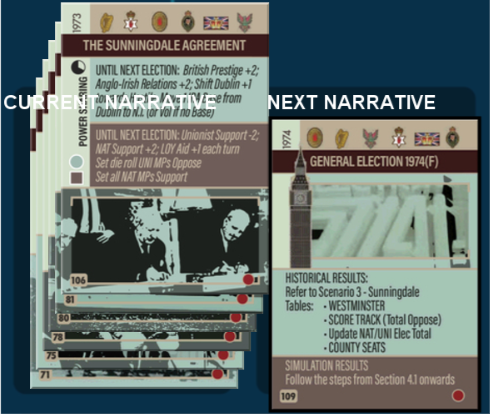

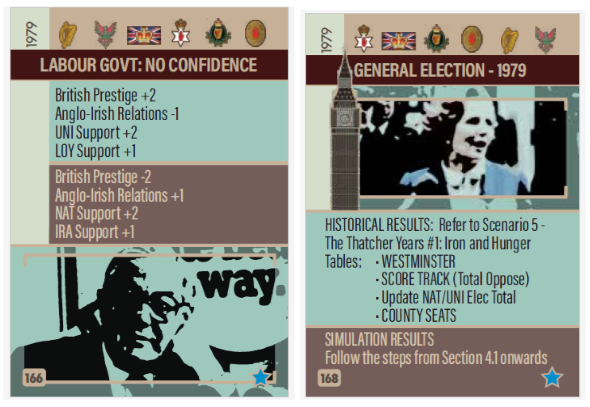

Each Scenario (named an ‘Epoch’) contains a specific series of narrative cards, each of which represents an actual event from the Troubles. Mainly episodic in nature, these artefacts depict a day or a succession of days in the historical timeline of Northern Ireland between 1964 and 1998, and each card has an accompanying summary of the actual event in the accompanying documentation. The symbology (see Figure 5) and colors are authentic and continue to evoke emotional responses.

1966 witnessed the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, a commemoration of the IRA’s failed attempt in Dublin to secure Home Rule. Republican celebrations led to one specific incident contravening Northern Ireland’s Flags and Emblems Act of 1954, which saw an Irish Tricolour (the flag of the South, Republic of Ireland) being displayed in the window of a Sinn Fein office in the west of Belfast. Rioting ensued after Rev Ian Paisley threatened to march and remove the offending article, with the Royal Ulster Constabulary deploying 350 police officers to restore order—after two attempts to remove the flag: non-Union flags were disallowed if they were deemed to threaten the peace. Nationalists deemed that this law primarily discriminated against them.

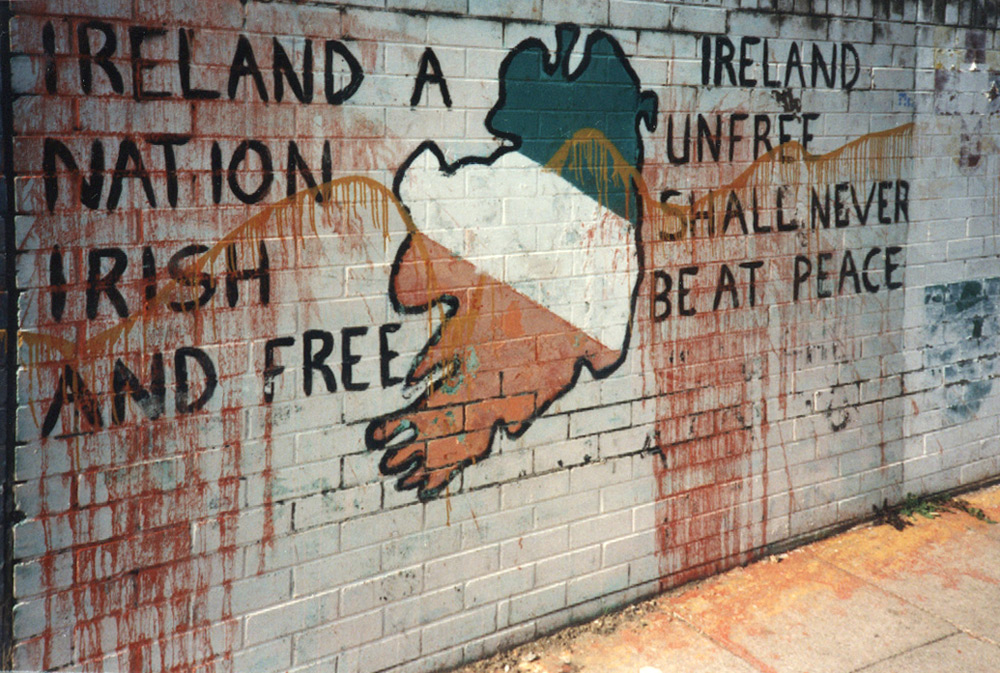

Protestants and Unionists in Northern Ireland cling to the Red Hand of Ulster and the Union Jack; the color orange, the ‘sash’ collarette, King William of Orange, “No Surrender”, and marching flute bands. On the other side of the divide, the Harp is a Catholic, Nationalist symbol connoting the entirety of Ireland and therefore island’s separateness from Great Britain; the color green defines their affiliation to the Republic of Ireland, slogans such as “Brits Out”, and the image of a phoenix rising from the flames—the transformation of the IRA becoming the Provisional IRA.

These are no mere shibboleths. Fiercely guarded, these images and sounds and cultural acts are integral to each community’s identity and belonging, used to forge identity in the face of threat or division in a land that is physically, socially, and politically divided. These are commonplace items—the cubes, hexagons, and cardboard counters; but their ‘contents’ are semiotically invaluable—a matter of life and death.

Placing a Political Influence counter in a County Seat area on the map that is defined as Unionist should instill in the faction player the tension that would have been present at that time, canvassers with loud hailers and leaflets—often identified as undemocratic since they were ostensibly the public face of the terrorist organizations with which they were affiliated (rightly or wrongly)—exhorting the need for peace, a time to vote for change, or to maintain the status quo.

Hegarty elucidates on the authenticity of each of the 260 unique narrative cards present in The Troubles, many of which feature a still image derived from the medium of the time (see Figure 12):

The images are meant to evoke the main media of news in my youth—newspapers, with TV style and color coming later in the cards. They are meant to be rough and a bit fragmentary like many of my memories of the Troubles. I remember mistaking an image of bombed out Beirut for Belfast when I was still in primary school…Hard black/white contrast like the narratives of the sides.

Source: VASSAL, from The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

As with the other components in The Troubles, each narrative card provides an episodic narrative element, which is drawn from an actual historical event. Most cards also provide the executing faction with an ahistorical alternative.

To the designer and those that lived this terrible period, there is obviously cultural import to each aspect of the design of this simulation drawn from many dimensions of personal experience, domestic, scholastic:

the color scheme was the colors of my youth—not just in print design but school wall, public spaces etc…it’s a palette of what I remember from the late 70s and early eighties rather than anything else. The pic treatment is again how I remember newsprint and early photocopies and spirit prints run off by the teacher. coarse and dark and hard to read.

From the narrative card imagery and the paratextual elements—the rulebook and historical supplement (see Figure 13)—players are under no illusion that they are dealing with anything other than actual events, many of which involved atrocities and the fatalities of approximately two thousand innocent human beings.

Source: The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland. Reprinted with permission from Compass Games LLC.

Value

The fourth and final characteristic defined in Leinhardt and Crowley is the value of an object: its physical uniqueness, and both its monetary and emotional cost.

Each playable Faction in The Troubles has a limited number of physical components and abstract Resources with which to carry out actions that facilitate their manipulation. A single Resource value or wooden component holds the power to control a map location by the barrel of a gun or generate income through extortion of local business owners; to decimate or degrade the opposition using Semtex or bullets; or to change the course of elections and affect the overall power balance for a community that feels second class or forgotten. A player may use a counter or wooden component to declare a Ceasefire and embark upon the Peace process. The inherent value of each individual piece mimics the currency of terror; they are also the currency of peace.

The inherent value of an object in a simulation—its functional and symbolic value—is a powerful motivator in strengthening the realism and therefore the sense of agency afforded play. However, thematically, the civilian counters are representative of lives lost, fatalities indirectly affected by operations undertaken by all sides. They represent the wrongly imprisoned and tortured; for being in the wrong place at the wrong time; or being in the right place at the wrong time. They represent those people who still live with these past events even to this day, and to this stark realism the value of a component should also afford sensitivity.

Neitze defines narrative structure as a “double temporal sequence…the time of the thing told and the time of the telling.” This “Story Time and Narrative Time” allows players to discuss a powerful story that has become abstract over time but now appears ‘on the table’ in very concrete terms, the objects—cube, hexagon, counter, narrative card—anchoring it in historical detail.

Each individual narrative card is historically significant, affecting the course of the narrative—or not, enhancing or limiting the activities of a faction—permanently or temporarily. Behind each card are real people, places, and events; each card—each life—unique.

The “semantic nets” of meaning that develop across the various simulation artefacts during play are grounded in historical detail.

Many objects represent the actual victims, combatants, and materiel. And in this way the object “enlivens” discussion through the appropriation of the object, whereby new concepts and impressions of a historical event can evolve, and in discussion of these ideas they can be applied to the physical space in front of the players in concrete terms, generating the possibility that generalizations and abstractions may be applied to current and future conflict situations.

Museums and simulations of difficult and often controversial periods of history both “curate difficult knowledge”. But it is how to “transform the game experience into learning” that is key to experiences involving both museums and tabletop simulations, and an ethical imperative as the following section discusses.

Discussion: Curating History Learning

Historical Narrative

The objects of The Troubles are less unique than pieces in an exhibition; however, they are finite in number and do represent a limited number of actual lives and multifarious materiel.

When placed, an object in The Troubles can have both their inherent status change as well as be changed depending on physical positioning from what has been created by the game designer and authored by the players.

A counter or an object may carry one connotative impression in a specific area of the map, generating a completely different set of connotations in another. Objects themselves may have an inherent mechanic—a status, whereby it may adopt a dual-identity. Furthermore, this oscillation of meaning attached to an object may also be affected by the presence (or absence) and proximity of another object(s): objects may be complementary, supplementary, or providing an oppositional force between each other.

This interplay of each faction’s forces and counters, each conveying different meaning depending on their inherent status and their physical location on the map and the meta-mechanics of the story arc, their proximity to other ‘nodes’ in the emergent constellations of meaning, creates a dynamism. Each sparking connotative ideas and facilitating these constellations of narrative threads and thematic tensions.

Historical Identities

Players ‘visiting’ The Troubles are invited to assume one of the six identities that have been implemented, where the mechanics model the historical structures and constraints that allow players to internalize the perspectives of their faction, not just the historically grounded agency of making strategic decisions. Further complicated as play progresses and the narrative context adapts to activity from the players and thus altering co-operation and competition considering changes to goals or victory conditions. Players can, collectively, create exhibit narratives for others to consider acting as both curator and visitor; they experience and interact with their own and the nodes of others.

It is hoped that new knowledge about the conflict in Northern Ireland will be gained as well as allowing those who experience The Troubles to apply the theme to other contexts and locations in time, taking the abstract from the concrete game play around the table. Players, like visitors, may forge a variety of routes through the exhibition that is The Troubles; each time they ‘visit’ will differ depending on which faction they have chosen as their particular vehicle, as well as those with them. In this way the players themselves are actors in the narrative, the story that has been weaved together from the object nodes; the players are narrating from experience, not from didactic memory.

Unlike museum participants, players are identified with/immersed within/anchored to a particular faction in game; a more concrete presence in the space on the table as opposed to a museum. When they discuss during and after a session, they are making sense of, questioning, and critiquing a narrative that is historically bound but also co-created and emerging by themselves and those with whom the table is shared. This makes the simulation experience similar and different in relation to identity.

How and When Learning Takes Place

Visibility

Unlike patrons and visitors to a museum, players have an almost omniscient view of the components and the simultaneous narratives; there are some gnoseological elements of design in order that the daily (and almost hourly) randomness of events may be simulated: there are random event chits (RECs) which allow players to play—or cancel—a prescribed action immediately; the narrative card deck displays only the current and next card in the sequence, leaving the other cards hidden.

However, a key feature of simulations is that all players are in close physical proximity and can witness every action and articulated, verbal and non-verbal, decision.

Curation in Simulations

Unlike museum artefacts, which are fixed in situ even if they may be manipulated, objects of a simulation are bound by the “environmental response rule” and are therefore relocatable but within rules that limit or facilitate this movement. Players of simulations have more control in the curation of what components are in front of them. Their repositioning is often expedient and motivated by achieving victory.

Differing from a museum, the participants themselves act as the curators, with the nodes appearing and shifting more frequently than objects in an art gallery or museum. What is present, what is absent; how each object relates to the other depends on the players themselves. This invisible tension exists, an invisible thread of dynamism, the players forging or blocking the routes through which the session shall run.

Narrative Routes

As with visibility of components, players may see all the possible routes available to them: they are afforded more choice, more options. The physical space and organization of routes through a museum exhibition is relatively static: visitors may choose to look at and examine any number of objects which have been curated, selected, and placed in a particular area and next to other objects for practical or thematic reasons. This is the authorship referred to as being performed by an “implied author.”

There are similarities with The Troubles and similar simulations, the story is chosen, rules derived or applied to the idea. However, through the mechanics of play and the ‘environmental response rule,’ the co-construction and co-authorship of the game’s story introduces a state of flux, creating—deliberately or unconsciously—these pathways, limiting or even disabling route to and from particular geographic or political areas. In this way, the players create episodic sub-narratives, all within an overarching meta-narrative as items are variably placed, creating relocatable nodes that can have binary or non-binary weightings of meaning.

Debriefing: Listening and Talking

Learning in tabletop simulations occurs dynamically during gameplay and is further enriched through discussions and debriefing sessions, making both aspects essential for a comprehensive learning experience. According to Crookall, the discourse that occurs during and after engagement in any simulated activity is just as important as the design of the physical components and the mechanics:

game design should start with the place where the participants are going to learn, that is, with the debriefing. At the very least, the debriefing should be a design consideration right from the start.

Similarly for museums, the key message is that “conversation is a primary mechanism of knowledge construction and distributed meaning-making,” and this should underpin the understanding as to the metacognitive efficacy of any museum learning experience.

Engaging in discussion about controversial issues helps in the development of four key skills in any citizenry: to make judgements that are critically-based; the use of evidence from a variety of sources; recognizing the polyvocal and conflicting nature of the points of view of others; the democratic necessitude for compromise. Talking and Listening are integral to the ‘Four Capacities’ of Literacy: to “explain, instruct, question, analyze, speculate, imagine, discuss…” is essential to both learning and the development of empathy.

The very nature of games-based learning and simulations such as The Troubles are non-repetitive and offer a unique experience in each game session. In this way, such simulations offer a multitude of experiences and situations upon which players can engage critically and discursively.

Each object is important in itself—the map, the narrative cards and each wooden component that encapsulates four aspects particular to ‘exhibits’ and which are symbolic and operate within the authentic social and cultural boundaries that have been authored by the designer and emergently co-authored by the players themselves.

This paper highlights that both designers and players can gain emotionally and cognitively from the experience, akin to the engagement with physical artifacts in a museum. This suggests that learning is not confined to the act of playing but is significantly enhanced through reflective discussions afterward. In more formal educational contexts, the teacher plays a crucial role as a facilitator. They may guide discussions during and after gameplay, helping students reflect on their experiences and the historical context of the game. Educators may also integrate use of The Troubles within a curriculum that already draws incorporates documentaries, other primary sources, and other educational media alongside gameplay. The Troubles accommodates being used to study specific periods, even allowing the focus to be on specific months or even days of this conflict.

Bias

The domain knowledge used to construct the narratives within The Troubles game is based on historical events, providing players with a mix of both historical and counterfactual play options. The game designer aimed to present a balanced view by incorporating multiple perspectives and allowing players to engage critically with the complexities of the conflict. As with museums, any curation is based on omission and commission. To mitigate such potentialities, considerations of objectivity and potential bias were addressed by:

- collaborating with historians, political scientists, ex-military personnel;

- providing a historical context through supplementary materials, extensive bibliographies;

- including ahistorical alternatives in the narrative cards, enabling players to explore different outcomes and perspectives while maintaining historical accuracy;

- including diverse perspectives, moving from an oversimplification of what were tragic events;

- sensitive visual representation that took cognisance that many events focused on individual, familial or community suffering.

Future Research

The author intends to investigate the longitudinal impact of The Troubles on empathy development in diverse educational settings, focusing on how different demographics respond to its historical narratives.

Mixed methods approaches could explore the effectiveness of the various game mechanics and their efficacy in enhancing emotional engagement and understanding of the Troubles, assessing which elements resonate most with players, and in particular the linguistic features that constituted the emerging oral narratives. This may present opportunities to analyze the portrayal of historical events and characters to identify potential biases and their effects on players’ understanding and empathy towards different perspective. Alternatively, the simulation may not adequately address the emotional impact of certain historical narratives, which presents the potential for The Troubles to develop and grow, shaped through the reflexivity of play and feedback from players.

And with or without the presence of a teacher, lecturer or other learning facilitator to mediate and support a deeper understanding of the curriculum presented, there are opportunities to conduct comparative studies between existing and more traditional educational methods of teaching the conflict of Northern Ireland, and simulation- and game-based learning approaches to determine the relative effectiveness in fostering empathy and critical thinking about historical conflicts.

Conclusion

The Troubles provides the potential of serving as an appropriate medium through which to support the teaching of the Northern Ireland conflict known as the Troubles. Viewed through the lens of Historical Memory Education (HME), we should encourage participants to obtain and develop skills and knowledge as they think critically and reflexively about the complex socio-economic and historical contexts in which they find themselves.

From an ethical and pedagogical standpoint, narrative-based simulations such as The Troubles are designed to provide an immersive and authentic medium that provides the necessary social context to support a safe and sensitive exploration of a controversial and harrowing period in history. Participants are given free agency to engage with their own and that of others’ “political and ideological positionings…related not only to knowledge, but also to action”. Players—students—of The Troubles should be active author-readers in this history; from an ethical and pedagogical standpoint, simulations like it provide unique opportunities that other, more traditional forms and modes of instruction often do not or cannot, particularly agency.

Just as museum visitors can choose to navigate through exhibits in different ways, players of The Troubles have the agency to approach the game from various perspectives. Unlike traditional mediums, The Troubles provides an innumerable constellation of objects and cards constantly creating a multitude of narrative nodes and nets of possibility for the student of history.

By drawing parallels between museums and tabletop games in facilitating engaging learning experiences, designers and players of controversial simulations like The Troubles co-author powerful and polyvocal narratives of the past. Through this collaborative process, players gain historical knowledge while engaging in the cycle of historical empathy, critically and morally participating in some of the most complex and harrowing historical contexts.

Acknowledgements

This research is dedicated to those who were directly and indirectly affected by the Troubles in Northern Ireland. I acknowledge the immense suffering and trauma experienced by individuals, families, and communities during this challenging period. I extend my deepest sympathy and respect to those who lost loved ones, endured hardship, or were impacted by the violence, conflict, and division.

I am grateful to the survivors, witnesses, and individuals who shared their stories and experiences, often under difficult circumstances, for the purpose of this research. Their courage and resilience in the face of adversity have profoundly shaped this work.

This research aims to contribute to the ongoing efforts of understanding and healing, and I hope it offers a small part in the broader dialogue of reconciliation and peace.

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Liz Boyle and Murray Leith for their invaluable guidance, support, and encouragement throughout the course of this research. I also wish to thank Thomas Ambrosio for his assistance and for his invaluable work on historically-structured boardgames (HSBGs).

Special thanks to my colleagues and friends, Hamish MacLeod, for their insightful feedback and moral support.

Lastly, I would like to acknowledge my family for their unwavering support and encouragement, which provided me with the strength to complete this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author of this paper was involved in designing The Troubles: Shadow War in Northern Ireland 1964-1998. The author has received no funding for the production of this paper.

Games

Hugh O’Donnell. The Troubles. Compass Games LLC, 2026.

Jason Matthews and Christian Leonhard. 1960: The Making of a President. GMT Games, 2007.

Frédéric Serval. Red Flag Over Paris. GMT Games, 2021.

Volko Ruhnke. Labyrinth. GMT Games, 2010.

–

Featured image provided by author. Used with permission.

–

Abstract

There are a multitude of digital and analogue games and simulations that place players in historical situations. However, there is a dearth of such mediums that foreground the human cost to both the historical actors being studied and players themselves. This paper suggests that approaches to recent controversial conflicts should be undertaken through the medium of narrative-based games and simulations. It focuses on how game design can lead both designers and players to gain emotionally and cognitively in the same way that visitors do when they visit a museum and engage with the physical artefacts on display.

Keywords

game design, narrative games, game-based learning, tabletop simulations, museums, history, conflict, Northern Ireland, the Troubles

–

Hugh O’Donnell has been interested in narrative-based game-based learning for the past 15 years, which resulted in successful Masters-level study at Edinburgh University in 2014. Since 2015, Mr O’Donnell has been researching and designing ‘The Troubles’, a narrative-based simulation of the Troubles of Northern Ireland, which is scheduled for publication in 2026 by Compass Games LLC.