Introduction

This article examines tabletop role-playing game (RPG) activities at Gen Con, the original, longest-running gaming convention in the world with 70,000+ annual attendees as of 2023 and a local economic impact near $75 million. Gen Con’s early history and its ties with Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) have been addressed elsewhere, and Gen Con is featured in Shannon Appelcline’s four-volume history of the RPG industry. My approach to the convention differs in that I base my inquiry on the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset of all Gen Con events between 1967 and 2017. I use the dataset to document two key characteristics of Gen Con RPG events over 50 years: 1) a long-term and increasing transmedia presence, and 2) an overlooked educational function as a format to teach and learn about gaming.

As a result, the convention event data helps to achieve a more precise historical understanding of embodied RPG culture and related transmedia. My singular examination of Gen Con can be read alongside scholarship focused primarily on San Diego Comic-Con, wider spatial transmedia and fan convention contexts, and specific fan activities like LARPS or cosplaying that take place at conventions. A challenge, though, is the extent of Gen Con event data. If a linear progression through 160,000+ events is a methodological will-o’-the-wisp for some magic grimoire illuminating all things Gen Con, my Best 50 Years of Gaming dataset analysis instead offers a scholarly playtest via six modular encounters with big data.

Module 1: Formative Years for Gamer Fandom and Transmedia: 1968-1977

The search engine to the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset generates listings of Gen Con events, and the convention’s relatively small, formative 1968-1977 iterations in Lake Geneva, WI make for manageable results. Although RPG experiences at Gen Con did not begin until 1974, the convention’s first seven years set the foundations for event types that would proliferate. The inaugural 1968 convention had two events: “Fight in the Skies” was a World War I aerial combat game while “Naval Gaming” allowed for various games under a thematic label. These two initial event types remain fundamental today: specific game system events—Fight in the Skies is the only game to be played at every single Gen Con—and thematic events like the railroad games later organized by the Train Gamers Association.

Gen Con event types still operative today were added between 1969 and 1974. The 1969 convention included an opening speech, an auction, three wargaming miniatures events, and a Diplomacy game tournament. While these 1969 events did not involve RPGs, they created formats for future Gen Con RPG activities. Today, these event types include both RPGs and a multiplicity of branded game systems and kinds of games (e.g. the auction now contains slots for RPGs, miniatures, board games, card games). The 1971 Gen Con was the first with event types that educated players how to play games, introducing the concept of the tabletop gaming convention as a site for teaching and learning. In this 1971 case, neophytes were introduced to armored vehicle wargames and “likely medeaval [sic] or fantasy [miniatures] for amateurs only.” That same year also saw the first event referencing a gamer organization, the International Federation of Wargaming general meeting. The 1973 Gen Con then became the first to create event types for trophy presentations and open gaming. While these early event types seem unexceptional, consider that gamers over 50 years later still structure their organized play in terms of e.g. open gaming, sanctioned tournaments, and differential player knowledge brackets. As the earliest and still preeminent gathering of game enthusiasts, Gen Con shaped gamer culture in ways completely taken for granted.

In addition to establishing normative gaming event types, Gen Con offered transmedia options. The year D&D debuted, Gen Con’s 1974 schedule included three “Movie” slots. Although the films shown in 1974 were not RPG content, they attest to the centrality of the visual arts at the world’s first and foremost gaming convention in which RPG events came to occupy a prominent place. In 1975, the kickoff gaming event was a Dungeon! tournament spotlighting Dave Megarry’s D&D board game counterpart. This was the first year that Gen Con was run by TSR, Inc., the producers of D&D, and the decision to start the convention with a spinoff to their flagship product set the tone for a nominal RPG industry that leverages transmedia to this day. Meanwhile in 1975, D&D co-creator, Dave Arneson, organized one of the three “Fantasy (Miniatures)” events that moved figurines from wargaming into RPGs, and in so doing charted another transmedia vector for the new industry. There is a critical point about recursion to understand with RPG transmedia; even a glance at Gen Con events shows how the RPG industry built on board game and tabletop miniature antecedents before absorbing them as part of a broader, transmedia business strategy.

Gen Con 1976 event data suggests an expanding RPG trajectory. Expansion occurred via an increase in RPG events and through transmedia hooks to the RPGs. The largest event with 100 maximum players was “D&D Adventures” and that year TSR supplemented their core RPG with a “D&D Miniatures” event and a Dungeon! board game event. Gamers could still attend two “Movies” slots or try something new and learn about the launch of TSR’s Empire of the Petal Throne. Originally a self-published 1974 RPG by University of Minnesota faculty member, M.A.R. Barker, the Tékumel setting’s intricacy resulted in one of the first three seminar events held at Gen Con. The event description highlighted Barker’s academic credentials, while the other inaugural seminars featured award-winning fantasy author, Fritz Leiber, and a D&D seminar by creators Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson, and TSR employee, Rob Kuntz. The seminar with Leiber was the first time a literary inspiration for D&D appeared at Gen Con, and in a further transmedia twist, that year saw TSR demonstrate a board game about his fictional city of Lanhkmar from the “Fahfrd and the Grey Mouser” series.

The tenth anniversary of Gen Con in 1977 was the last to be held in Lake Geneva, WI and the event data reveals further transmedia growth. “Computer Games” are listed as three events—out of approximately 100. Three “Movies” slots remained on the schedule plus 12 D&D events including separate ones geared for novices, a miniatures time slot, and a “Greyhawk D&D Adventure” set in Gary Gygax’s campaign world that became the first de facto brand setting—and template transmedia catalyst—for TSR’s RPG. Instead of one there were two “D&D Seminar” events, plus Fritz Leiber returned to deliver a seminar for a second year. TSR continued to grow its Gen Con RPG programming, supplying three Empire of the Petal Throne events (one seminar and two adventures) and five Metamorphosis Alpha events (one seminar and four adventures) for its new, and the industry’s first, science fiction RPG. The adventures offered the gameplay usually thought of when someone says “gaming,” whereas the seminar event type organized an environment where gamers could variously teach and learn about RPGs. This second type of event has never been the focus of attention by scholars even when they insightfully address the knowledge pursuits of RPG enthusiasts. For example, Evan Torner’s “RPG Theorizing by Designers and Players” mentions Gen Con and other conventions but then instead examines written RPG theorycrafting in the form of web sites, fanzines, blogs, et cetera. As Gen Con prepared to move away from Lake Geneva, WI, its RPG events were already encoded with a transmedia presence and an educational function that would remain constant over time.

Module 2: Gamer Fandom and Transmedia at University of Wisconsin-Parkside: 1978-1984

Gen Con relocated to the University of Wisconsin-Parkside following its tenth anniversary and the number of events plateaued around 155-188 per year between 1978-1980. The stable number of events for this period enables an RPG industry snapshot of TSR’s dominance. Their D&D Basic Set (1977) and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D) (1978) RPGs combined for 18 of the approximately 188 events in 1979, 35 of the 155 events in 1979, and 31 of the 185 events in 1980. Other TSR RPGs like Empire of the Petal Throne, the post-apocalyptic Gamma World (1978), and the spy-themed Top Secret (1980) made for a combined 17, 20, and 13 additional events for those three years. Meanwhile, new RPG companies like Chaosium and their RuneQuest product tallied one event in 1978, eight in 1979, and six in 1980.

The initial three years at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside were significant for the growth in Gen Con seminars that offered teaching and learning about games. While the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset lacks detail, paradigmatic seminar types that still thrive today became apparent starting in 1978. A first type consisted of a game company like “Seminar SPI” presenting a specialist, real-time infomercial with gamers and designers in the same room. A second type covered a gaming-related topic like “Seminar: Napoleonic Armies,” where fans swap perspectives. Such in-group conversation is a hallmark of what Benjamin Woo has labelled the social worlds of geek culture, including fan conventions: “Demonstrating knowledge about the practice in which they engage is one important way that participants assert their right to be included within subcultural spaces.”

A third type of paradigmatic seminar, most prevalent, testified to foundational attributes of gamer culture in terms of player work. On the one hand, Gen Con 1978 attendees could try a “Seminar Dungeon Mastering” [sic] with Gary Gygax, thereby trying to optimize their in-game skill. It takes diligence to be a Dungeon Master and Gen Con began providing instructional material to this effect. On the other hand, Gen Con 1978 attendees could choose events like “Seminar Submitting Game Designs to Publishers” run by TSR’s Mike Carr, or “Seminar Designing/Selling Wargames” with independent company owner, Lou Zocchi. The Zocchi seminar was unprecedented in charging an extra $2 admission and suggests an early instance of another form of player work: gamers as creators, or per Brooke Duffy, “aspirational laborers [that] seek to mark themselves as creative producers who will one day be compensated for their craft.”

From the vantage of 21st-century scholarship on videogames and transmedia fandom, Gen Con events circa 1978-1980 are prophetic but overlooked. Writing on the “new participatory culture,” Henry Jenkins urged scholars in 2002: “Rather than talking about interactive technologies, we should document the interactions that occur among media consumers, between media consumers and media texts, and between media consumers and media producers.” Clearly such exchanges were underway at Gen Con decades before mainstream Internet, along with gamers toiling for the sake of self-improvement and, in some cases, future employment. “Play is no longer a counter to work. Play becomes work; work becomes play,” asserts McKenzie Wark’s about video gamer activity. Thanks to scholarship, video gamer activities are now equated with labors that range from in-game performance (e.g. grinding) to work-intensive activities outside of a game that involve, among other things, helping the overall player base (e.g. walkthroughs), attempting to produce new game variants (i.e. mods), and game-related artifacts like fan fiction, cosplay, machinima and more. The affirmation of video gamer “productive play” is welcome, but scholars would do well to recognize that tabletop gamers were likewise busily engaged years in advance of digital transformative works and cultures.

Gen Con seminars from 1979 and 1980 indicate a robust metagame that predates social media, podcasts, websites, et cetera. While academic definitions of metagame are difficult to pinpoint per Boluk and LeMieux, Elias, Gutschera, and Garfield provide a synopsis:

The metagame is the ‘game outside the game.’ It includes all the activities connected with the game that aren’t part of playing the game itself, such as tournament programs, online forums, magazines about the game, training and preparation players might do before the game, or even daydreaming about the game or staring lovingly at game equipment.

More definitional specificity might be helpful, but nonetheless, an analysis of the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset excavates early metagame behavior during the University of Wisconsin-Parkside era. A 1979 “Civil War Firearms Seminar” was the first to connect games with player interest in authenticity, setting the tone for 1980 RPG seminars like “Realism and Playability in Fantastic Combat.” Also new in 1979, the game industry itself was a topic in “The Future of Fantasy Adventure Gaming” and “Is Bigger Better?” The 1980 Gen Con then became the first to hold miniatures painting seminars (i.e. material culture DIY), historical self-reflection in the form of Gary Gygax’s “D&D—Where It’s Been and Where It’s Going,” and an “informal idea exchange session” entitled, “Computers in Fantasy and SF Gaming Workshop.”

Gen Con events at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside increased from 185 to 662 between 1980 and 1984. The increase makes it difficult to perform a close reading of events, but the convention organizers categorized their program with metadata in 1980, 1981, and 1983. A distant reading analysis is possible as a result. Following the creators of the Best 50 Years in Gaming:

Distant reading is taking a corpus of works, in this case the Gen Con programs, and using technology to ask some broad questions. It’s a great way to start research and identify questions, but close reading is almost always necessary to see what is really going on. Close reading is likely what you already do when working with a text: reading something line by line and interpreting that small section as you take it in.

While metadata varies between years, it is easy to reassign events to a unified category for longitudinal comparison:

| Table 1. Gen Con Event Type Category Frequency: 3-Year Comparison: UW-Parkside | |||

| Category |

1980 |

1981 |

1983 |

| Overall Total |

185 |

248 |

396* |

| RPG |

59 |

115 |

214 |

| Miniatures |

48 |

51 |

56 |

| Board Games |

44 |

46 |

60 |

| Seminars/Panels/Other |

34 |

33 |

58 |

| Computer Games |

0 |

3 |

4 |

| Proto-LARP** |

0 |

0 |

4 |

| Notes. * The search engine registers 397 events for 1983. Downloading the source event data in CSV format indicates that one event is a spreadsheet header row. ** “Proto-LARP” is my term for events categorized as “?” by the 1983 Gen Con organizers. These events required driving a car around the Parkside area with RPG instructions. | |||

Comparison of 1980, 1981, and 1983 suggests trends. Most pronounced, there is a continual increase in the total number and overall percentage of RPG events relative to all Gen Con events in a given year (31.89% in 1980; 46.37% in 1981; 54.04% in 1983). Miniatures events remain somewhat constant in total numbers but decrease in overall percentage (25.94% in 1980; 20.56% in 1981; 14.14% in 1983). Board Games events also remain somewhat constant in total numbers but decrease in overall percentage (23.78% in 1980; 18.54% in 1981; 15.15% in 1983). The total number of Seminars/Panels/Others and overall percentage relative to other event types fluctuates but shows the least variation for the period (18.37% in 1980; 13.30% in 1981; 14.64% in 1983).

Module 3: Licensed RPGs and Gamer Fandom Transmedia Remix: 1976-1980s

The year, 1981, saw new D&D competitors in the form of licensed RPGs published by Chaosium: Strombringer based on Michael Moorcock’s Elric of Melniboné fantasy fiction, Thieves’ World based on the shared-world fantasy series created by Robert Lynn Aspirin, and Call of Cthulhu based on H. P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos. Although Chaosium’s transmedia strategy had been preceded by two licensed RPGs from other companies—Star Trek: Adventure Gaming in the Final Frontier (Heritage, 1978) and Dallas derived from the TV soap opera (SPI, 1980)—these ventures were largely unsupported. Chaosium’s concerted transmedia strategy, on the other hand, presaged RPG product launches throughout the decade. As evidenced in the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset, RPG spinoffs involved different game companies and licensed media. In chronological order for the decade, the RPG licenses were James Bond 007 (Victory, 1983), Star Trek (FASA, 1983) and its bundled, Star Trek Starship Tactical Combat Simulator board game (1986), ElfQuest (Chaosium, 1984), The Adventures of Indiana Jones (TSR, 1984), Marvel Super Heroes (TSR, 1984), Middle-earth Roleplaying (ICE, 1984), Doctor Who (FASA, 1985), Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles & Other Strangeness (Palladium, 1985), Conan (TSR, 1985), DC Heroes (Mayfair, 1985), Ghostbusters (West End, 1986), and Star Wars (West End, 1987).

The licensed RPGs met with mixed success as reflected in Gen Con event frequency. Industry leader TSR experienced failure with Conan and The Adventures of Indiana Jones derivatives whereas its Marvel Super Heroes gained traction. Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu demonstrated staying power, and FASA’s Star Trek increased its Gen Con presence over the decade. None of the licensed RPGs challenged the supremacy of D&D during the 1980s, even so, but in their collective impact the transmedia RPG concept was entrenched by 1989.

| Table 2. Gen Con Event Frequency: Licensed RPGs: 1980s (Includes Seminars) | ||||||||||

| RPG TITLE | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1985 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 |

| Stormbringer | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Thieves’ World | 1 | |||||||||

| Call of Cthulhu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 19 | 18 | |

| James Bond 007 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Star Trek | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 15 | 10 | |||

| ElfQuest | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Indiana Jones | 1 | |||||||||

| Marvel Super Heroes | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Middle-earth…. | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Doctor Who | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||

| Teenage Mutant…. | 2 | 4 | 3 | |||||||

| Conan | 1 | |||||||||

| DC Heroes | 2 | 4 | 5 | |||||||

| Ghostbusters | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| Star Wars | 2 | 7 | 5 | |||||||

| TOTAL | 1 | 3 | 11 | 22 | 22 | 16 | 30 | 67 | 51 | |

It would be misleading to assert the rise of licensed RPGs as unique, however. As stated earlier, there is a key point about recursion to understand with RPG transmedia. The Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset shows how the RPG industry expanded upon licensed board game and tabletop miniature game transmedia antecedents before, in some cases, joining them as part of larger franchises. Prior to the 1981 appearance of any licensed RPG at Gen Con, there were licensed board game events starting with TSR’s Lankhmar based on Fritz Leiber’s “Fahfrd and the Grey Mouser” fiction (1976). Other licensed board games at Gen Con before 1981 were derived from science fiction/fantasy: Sauron (SPI, 1977) based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth, Darkover based on Marion Zimmer Bradley’s fiction (Eon, 1979), Dune (Avalon Hill, 1979), and Star Fleet Battles based on Star Trek (Task Force, 1979). In chronological order for the 1980s, additional board game licenses played at Gen Con were 221B Baker Street based on Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes (Antler, 1975), Doctor Who (Games Workshop, 1980), Federation Space based on Star Trek (Task Force, 1981), Judge Dredd (Games Workshop, 1982), Sanctuary based on Robert Lynn Aspirin’s Thieves’ World series (Mayfair, 1982), The Company War based on C. J. Cherryh’s Downbelow Station novel (Mayfair, 1983), Dragonriders of Pern (Mayfair, 1983), All My Children (TSR, 1985), Federation & Empire based on Star Trek (Task Force, 1986), ElfQuest (Mayfair, 1986), Arkham Horror based on H.P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos (Chaosium, 1987), Star Wars: Assault on Hoth (West End, 1988), Willow (Tor, 1988), Buck Rogers XXVC (TSR, 1988), The Hunt for Red October (TSR, 1988), Red Storm Rising (TSR, 1989), and prototypes of Myth Fortunes based on Robert Lynn Aspirin’s Myth Adventures novels (Mayfair, 1990).

| Table 3. Gen Con Event Frequency: Licensed Board Games: 1976-1989 (Includes Seminars) | ||

| Year | Board Games | Total |

| 1976 | Lankhmar (1) | 1 |

| 1977 | Lankhmar (3) | 3 |

| 1978 | Lankhmar (2), Sauron (2) | 4 |

| 1979 | Lankhmar (1), Darkover (1), Dune (1) | 3 |

| 1980 | Dune (1) | 1 |

| 1981 | Dune (1), Star Fleet Battles (1) | 2 |

| 1982 | Dune (1), Star Fleet Battles (5) | 6 |

| 1983 | Dune (1), Star Fleet Battles (11), Sanctuary (1), The Company War (1), The Forever War (1), Dragonriders of Pern (1), Dr. Who (2), Judge Dredd (1) | 19 |

| 1984 | Star Fleet Battles (8), Dr. Who (1), Federation Space (1) | 10 |

| 1985 | Star Fleet Battles (8), 221B Baker Street (1), All My Children (1) | 10 |

| 1986 | Star Fleet Battles (4), Dr. Who (1) | 5 |

| 1987 | Star Fleet Battles (2), ElfQuest (1), Star Wars (1) | 4 |

| 1988 | Dune (1), Star Fleet Battles (10), Dragonriders of Pern (1), 221B Baker Street (1), ElfQuest (1), Star Wars: Assault on Hoth (1), Arkham Horror (2), Federation & Empire (1), The Hunt for Red October (1), Willow (2), Myth Fortunes (1), Buck Rogers XXVC (1) | 23 |

| 1989 | Star Fleet Battles (10), Dragonriders of Pern (1), ElfQuest (1), Arkham Horror (1), The Hunt for Red October (1), Red Storm Rising (3), Sanctuary (1), Myth Fortunes (1), Buck Rogers XXVC (3) | 22 |

Licensed RPG and board game events at Gen Con during the 1980s often “stacked” to make larger franchises, such that the original, longest-running gaming convention in the world can be more accurately reframed as a transmedia convention. “Gamers” thus enjoyed the option of gameplay in at least two game formats and/or seminars about Buck Rogers, the Cthulhu Mythos, Dr. Who, ElfQuest, Star Trek, Star Wars, the Thieves’ World shared-world fantasy series, and Tolkien’s Middle-earth.

Paralleling the rise of licensed RPGs and board game events, transmedia mashups concocted by gamers were present in the RPG event listings from 1978 onwards. The first evidence of gamer remix events at Gen Con were “D&D on Barsoom” sessions in 1978 and 1979, relocating TSR’s ruleset to Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars fiction. “D&D in Pelludicar” then sourced Burroughs’s prehistoric world fiction in 1981. Bracketing Burroughs, the next recorded instance of a Gen Con gamer remix event is “Monty Python’s Flying Dungeon” in 1980—“An AD&D adventure of unknown origins.” The British comedy troupe’s work was then used with three 1980s RPG events including the “491st Annual Search for the Grail” Gamma World session in 1982 and a 1988 proto-LARP—“It’s Otter Stretching Time!”—that promised silly walks and more. Another British comedy –Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series—was remixed with both the Star Frontiers and Traveller RPGs in 1983 before a 1984 homebrew RPG event and “Rescue on Rendar,” a 1985 AD&D event advising attendees that a knowledge of both Doctor Who and Hitchhiker’s Guide would be helpful. In chronological order for the 1980s, additional transmedia gamer mash-up events with D&D or AD&D remixed Marvel superheroes (1981), Roger Zelazny’s The Chronicles of Amber (1982), Tolkien’s Middle-earth (two events in both 1983 and 1984), Star Trek (1986), and Fred Saberhagen’s Swords novels (1986). Meanwhile, Marvel and DC superhero characters figured in both Champions RPG sessions (two events in 1982, two events in 1983, two events in 1984) and Villains and Vigilantes RPG sessions (two events in 1982, three events in 1983). Keith Laumer’s “Bolo” fiction was used in an unspecified RPG event in 1983, and the Call of Cthulhu RPG remixed Scooby Doo for events in 1986, 1987, and twice in 1989.

Module 4: D&D RPGs Designed as Transmedia: 1984-1990s

1984 marked the last time Gen Con was held at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside and the first time a branded D&D campaign setting arrived at the convention. Acknowledged with hindsight as a “radical new multimedia venture” and an “epic transmedia campaign,” Dragonlance launched in Spring 1984 via a D&D module series. The brainchild of Tracy and Laura Hickman, Dragonlance’s world of Krynn was staffed with a designated studio team and by the end of the year featured as a calendar and as TSR’s first novel, Dragons of Autumn Twilight. Authored by Tracy Hickman and TSR editor, Margaret Weis, Dragons of Autumn Twilight revolutionized the RPG industry by opening a transmedia outlet for D&D novels, selling more than two million Dragonlance copies through 1987. As the decades passed, Dragonlance franchising included eight computer games, a comic book adaptation, and a direct-to-video film.

Against this backdrop, Dragonlance at Gen Con was part of a larger transmedia phenomenon reflected in the events. The 1984 launch comprised two RPG sessions, a seminar with the RPG design team, and “Dragonlance: Tales of Autumn”—“an evening of Drama and Song” offering spoken-word selections from the novel and music from the world of Krynn. Subsequent years through 2017 routinely included seminars about the campaign setting or writing topics with Dragonlance RPG designers and novelists, along with licensed product rollouts like computer games including Heroes of the Lance (1988), War of the Lance (1989), and Champions of Krynn (1990). Over time, Dragonlance events contributed to a performing arts presence at Gen Con. For example, 1996’s “Music of the Dragonlance Saga” event showcased Krynn songs and an audience sing-along. That same year, “The Dragonlance Skit” was impromptu theatre written and directed by Tracy Hickman, with attendees playing the roles aided by costumes and bespoke music. Such stagecraft, often with a Dragonlance theme or content, morphed into the “Killer Breakfast” hybrid RPG/interactive theatre events arranged by Hickman with hundreds of participants to the present day.

Other branded D&D campaign settings followed the Dragonlance transmedia template, and Gen Con events helped to introduce, explain, sell, and perpetuate RPG and other activities about these licensed worlds. Most notable was the Forgotten Realms (1987-present), which spawned numerous New York Times best-selling novels by R.A. Salvatore (1988-present), a DC comic book (1989-1991), dozens of computer games including the first graphical MMORPG (Neverwinter Nights, AOL, 1991-1997), and the groundbreaking hit, Baldur’s Gate (1998), that introduced BioWare’s Infinity Engine software environment to offer a top-down, third-person isomorphic gaming perspective in the form of an overhead diagonal view. The branded D&D campaign settings were envisioned for both RPG use and as media platforms. Major attempts were Spelljammer (1989), Ravenloft (1990), Dark Sun (1991), Planescape (1994), Birthright (1995), Eberron (2004), and the sporadic development of Gary Gygax’s Greyhawk setting (1980). During the 1990s, factoring in Dragonlance and the Forgotten Realms, there were eight branded D&D campaign settings each with their own transmedia.

The Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset enables comparison of the eight branded D&D campaign setting during the 1990s. The campaign settings are arranged as three bundles by release date and abbreviated with their first two letters so that Ravenloft = “Ra”, Spelljammer = “Sp,” etc. (Table 4). The table rows are shaded to indicate which setting bundle had the most impact during a given year. Dark grey shading denotes the “winner” in a year if either a bundle of new or legacy brand settings clearly had more Gen Con events than the other. Light grey shading indicates a year when new and legacy brand bundles had basically the same number of Gen Con events (variance <2). No shading indicates a “loser” in a year relative to a “winner.” The upshot is that no setting gained prominence. Despite all their transmedia product development during the period until the 1997 buyout by Wizards of the Coast, TSR could not maintain a branded D&D campaign setting that rivaled legacy worlds like Greyhawk, Dragonlance, or the Forgotten Realms. By the end of the 1990s, the halcyon D&D settings were once again more prevalent at Gen Con as overall convention attendance hovered in the 20,000s through 2009.

| Table 4. Gen Con Event Frequency: Branded D&D Campaign Settings: 10-Year Comparison: 1990-1999 | |||||

| Year | Events Per Setting 1989-1991 Brands |

Events Per Setting: 1994-1995 Brands |

Total Events: 1989-1995 Brands | Events Per Setting: Legacy Brands |

Total Events: Legacy Brands |

| 1990 | 20 Ra; 12 Sp | 32 | 21 Fo; 6 Dr; 4 Gr | 31 | |

| 1991 | 20 Ra; 15 Sp: Da 3 | 38 | 9 Gr; 7 Fo; 1 Dr | 17 | |

| 1992 | 75 Da; 61 Ra; 54 Sp | 192 | 24 Fo; 21 Dr; 5 Gr | 50 | |

| 1993 | 24 Ra; 4 Sp; 4 Da | 32 | 15 Fo; 13 Gr; 5 Dr | 33 | |

| 1994 | 15 Ra; 8 Da; 1 Sp | Pl 7 | 31 | 7 Gr; 6 Dr; 4 Fo | 17 |

| 1995 | 11 Ra; 7 Da; 0 Sp | Pl 6; Bi 6 | 30 | 5 Dr; 3 Gr; 4 Fo | 12 |

| 1996 | 10 Ra; Da 6; 0 Sp | Bi 7; Pl 4 | 27 | 11 Dr; 9 Fo; 5 Gr | 25 |

| 1997 | 8 Ra; Da 6; 0 Sp | Pl 15; Bi 8 | 37 | 14 Dr; 11 Gr; 5 Fo | 30 |

| 1998 | 9 Ra; 1 Sp; 0 Da | Pl 32; Bi 21 | 63 | 31 Gr; 25 Dr; 14 Fo | 70 |

| 1999 | 8 Ra; 0 Sp; 0 Da | Pl 23; 3 | 34 | 20 Gr; 14 Fo; 9 Dr | 43 |

Module 5: Paizo and Teaching and Learning about Pathfinder: 2009-2017

2009 saw the arrival of a new D&D competitor that altered the RPG landscape. By now, the “Best Four Days in Gaming” was a summer fixture at the Indiana Convention Center in Indianapolis and the venue soon underwent a $275 million expansion to retain Gen Con and its swelling audience. During this time of growth, D&D fourth edition (2008) proved controversial for overhauling the ruleset and the product range soon after D&D 3.5 edition (2003), for its emulation of computer game battle tactics, and for its Game System License that was more restrictive than the Open Game License packaged with 3.5 edition. Under the terms of the previous Open Game License, permission was given to make and distribute new RPGs using core D&D mechanics. Longtime D&D allies and designers at Paizo Inc. enacted the Open Game License to launch the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Core Rulebook for their ambitious 3.5 edition fantasy RPG variant at Gen Con 2009 after a one-year playtest. According to the best available industry estimates published quarterly at the ICv2 website (www.icv2.com), Pathfinder became the first RPG to outsell D&D between Spring 2011-Summer 2014.

Pathfinder’s influence was felt at Gen Con. Table 5 below compares Pathfinder RPG events organized by Paizo—both adventure sessions and seminars—with those run by Baldman Games, the Role Playing Game Association [sic], or Wizards of the Coast on behalf of D&D. Pathfinder’s ascension crested in 2013 before D&D countered with 2014’s fifth edition. Even after the success of D&D fifth edition, though, Pathfinder remained an RPG force as shown through Gen Con event frequency.

| Table 5. Gen Con Sanctioned RPG Event Type Frequency: 9-Year Comparison: Indianapolis | ||

| Year | Pathfinder | D&D |

| 2009 | 41 | 126 |

| 2010 | 87 | 166 |

| 2011 | 173 | 188 |

| 2012 | 201 | 213 |

| 2013 | 378 | 52 |

| 2014 | 224 | 84 |

| 2015 | 306 | 128 |

| 2016 | 233 | 178 |

| 2017 | 369 | 195 |

The Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset allows searching for patterns across Paizo Gen Con events. The majority were Pathfinder adventure sessions, but in any year, 5-10% consisted of seminars that were decidedly pedagogical. Close reading of the listings shows that one seminar type on the 2009 schedule educated gamers about Pathfinder play. For example, the “Pathfinder RPG Conversion & Creation Q&A” matched Paizo staff and volunteers with Gen Con attendees looking to either make a character or convert their existing D&D character to the new, rival product. A second type of seminar on the 2009 schedule educated gamers about the product line. For example, “Paizo’s Pathfinder Adventure Path Q&A” had Editor-in-Chief James Jacobs outlining the company’s campaign wares. A third type of seminar on the 2009 schedule educated gamers looking to freelance, such as “Writing for Paizo.”

The three-pronged pedagogical seminar strategy would be calibrated during the period to fit Paizo’s growth. Gamers keen to learn more about playing could partake of choices like “Pathfinder Roleplaying Game Rules Q&A” (2010-2017), “Pathfinder RPG Rules Design Workshop” (2012-16), and seminars dedicated to the needs of Game Masters beginning in 2012. Gamers interested in the transmedia product range could learn about spinoffs through seminars on Pathfinder fiction (2010-2014), computer games (2012-2017), the Pathfinder Adventure Card Game (2013-2017), and Pathfinder comics (2016). Gamers with gaming career interests could meanwhile attend seminars with titles like “How to Become a Contributing Author for Paizo Publishing” (2010-2011), “Secrets of RPG Editing” (2012), “Getting Started in the Industry: Freelancing and Self-Publishing” (2013), and “Project Management for Game Publishers and Freelancers” (2014).

A fourth, less frequent type of seminar taught gamers that Paizo was not just an ordinary company, but one with a history and a community. For instance, the company commemorated their past through seminars like “10 Years of Paizo Publishing” (2012), “Rise of the Runelords 5th Anniversary Round Table” (2012), and “Retrospective Panel: Open Source D&D” (2017). Similarly, “Auntie Lisa Story Hour” or Auntie Lisa Story Hour(s)” became an annual gathering from 2013 onwards for Pathfinder fans to listen to CEO Lisa Stevens reminisce about her years in the RPG industry, not unlike an older relative holding forth at a family reunion. In a different but related sense, Paizo seminars issued gamers an invitation to participate in the development of shared experiences. “Become a Pathfinder Sage” seminars held in 2013-2016 taught gamers how to join the PathfinderWiki community after 2011-2012 seminars showed gamers how to join the Pathfinder Society Organized Play network. “How to Organize a Convention” was a 2016 Paizo seminar, and ways to make Pathfinder “more inclusive and fun for people of all shapes, genders, sexual preferences, ages, ethnicities, and more” were tackled through “Diversity in Gaming” seminars between 2014-2016. Taken together, these types of seminars foreground the notion of a brand/fan community that has been labeled “brandom” in terms of Italian football supporters and “brandfans” generally in the public relations literature – “They experience an emotional connection to each other as well as the org/producer, and they expect authentic, human connection and feel a sense of ownership in the brand, organization, or product.”

Just as the Paizo seminars at Gen Con were pedagogical, so were a surprising number of the Pathfinder RPG adventure sessions. Every year starting in 2011, Paizo ran Gen Con adventure sessions to teach Pathfinder. “First Steps” Pathfinder adventure sessions in 2011 and 2012 could be played on their own or as part of a sequence that walked new players through archetypal locales. The latter year was the first Gen Con with Pathfinder Beginner Box events offering Paizo’s streamlined RPG product for novices, plus “Kid’s Track” sessions that used the Beginner Box ruleset to introduce Pathfinder to tables of four children, accompanied by their guardians. In 2016-17, the “Kid’s Track” sessions were folded into the “Pathfinder Society Academy” concept together with sessions reserved for families and older youth.

| Table 6. Pathfinder RPG Adventure Session Frequency: 9-Year Comparison: Indianapolis | |||||

| Year | Total Pathfinder Sessions | First Steps

Sessions |

Beginner Box

Sessions |

Kid’s Track

Sessions |

Pathfinder Society Academy Sessions |

| 2011 | 166 | 24 (14.45%) | — | — | — |

| 2012 | 178 | 27 (15.16%) | 9 (5.05%) | 14 (7.86%) | — |

| 2013 | 306 | — | 20 (6.53%) | 40 (13.07%) | — |

| 2014 | 202 | — | 14 (6.93%) | 28 (13.86%) | — |

| 2015 | 279 | — | 13 (4.65%) | 18 (6.45%) | — |

| 2016 | 205 | — | — | — | 28 (13.65%) |

| 2017 | 352 | — | — | — | 50 (14.20%) |

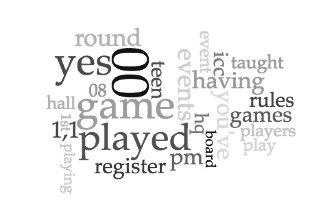

Paizo’s provision of pedagogical events at Gen Con is striking such that it could be mistaken as anomalous, but it actually reflects the corpus of the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset. An eureka moment happens when viewing a Voyant Cirrus word cloud visualizing the top-frequency words in the dataset between 1968-2017, with no attempt made to delete context-specific “stop words” (Figure 1). In the case of five decades of tabletop gaming convention event data, stop words could include locations such as “hall,” the need to “register” for “event/s” with “rules” that often have a “round” format, and ubiquitous words like “game” and “play/es/ed/ing.” A look at the Cirrus word cloud with no stop words is overall as expected: lots of what is essentially meaningless static. This visualization of 50 years of Gen Con event data—17,088,798 total words according to the Voyant Summary tool—could perhaps be used to confirm stereotypes about “teen” gamer night owls via the high-frequency word, “pm,” but the most glaring word by far is “taught.” In fact, the word “taught” leaps out and allows for a new way to think about Gen Con. Using the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset with Voyant Tools, moving between close and more distant readings to examine RPG events, is valuable.

Teaching is shown to be a main Gen Con event characteristic even in the raw data. The Voyant Terms tool detects 65,723 instances of the word, “taught,” and yields another 64,297 instances where “taught” collocates with “rules.” Although it comes as no surprise that rules have been taught for over 50 years at Gen Con, less manifest is the notion that the world’s premier gamer convention can be reframed in terms of teaching and learning. Gamers gather at Gen Con to play and to sample gaming-related transmedia, that seems obvious, but less discernible is that gamers go to Gen Con to learn about games and to teach each other about play. When RPG enthusiasts at Gen Con attend a Paizo upcoming products seminar or sit down for a demonstration of the next D&D edition, they are there to learn and to be taught. Education is likewise part of the mix when RPG fans organize a Gen Con seminar about how to be a better Game Master, or when they sponsor adventure sessions in a homebrew campaign setting built atop an existing game system. Such activities link with RPG companies whose business proposition is to sell instructional material in the form of rulebooks, campaign setting guidebooks, and modular adventures packaged with customizable story hooks and DIY advice. From Lake Geneva, WI in 1968 to the Indianapolis Convention Center today, Gen Con can be situated within a broader United States tradition of self-improvement vacations—“What attracted Eva Moll to Chautauqua was not merely its promise of amusement and relaxation, but also its extensive educational offerings.”

Module 6: Transmedia and Gamers as Teachers Learners: To 2017 and Beyond

Gen Con’s 50th anniversary convention in Indianapolis, August 2017, was a sold-out, four-day extravaganza with 60,000 attendees that generated $73 million after nine consecutive years of growth. Since relocating to the city in 2003, “The Best Four Days in Gaming” more than doubled in terms of attendance and expanded from a tabletop gaming convention per se where transmedia events always frequently took place, to a recognizably transmedia festival for gamers and families. Comparison of a chronological sequence of two-year intervals between 2003 and 2017 suggests two global trends (Table 7). First, there is 647% growth in the number of Gen Con events during the 15-year period (2544 total events in 2003, 19,001 total events in 2017). Second, beginning in 2007 Gen Con broadens its event category scope to encompass other media (Anime Activities, Entertainment Events, Film Fest), wider audiences (Kids Activities, Spouse Activities, Trade Day for educators, librarians, and retailers), and a rapidly-growing miscellaneous category for events that don’t fit elsewhere—“Isle of Misfit” (e.g. escape rooms, social paranoia games like Werewolf, laser tag, the Gen Con games library, the Gen Con collective art project, vow renewal ceremony, wedding ceremony…. This problematic category inflects overall numbers in that some of it is gaming and some of it is not).

| Table 7. Gen Con Event Type Category Frequency: 2-Year Interval Comparisons: Indianapolis | ||||||||

| Category | 2003 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 |

| Overall Total | 2544 | 5382 | 5741 | 6935 | 8706 | 11488 | 14398 | 19001 |

| RPG | 1209 | 2356 | 1788 | 1719 | 2029 | 2582 | 2994 | 4379 |

| Miniatures | 205 | 742 | 834 | 807 | 894 | 1092 | 996 | 1230 |

| Board Games | 823 | 1070 | 1262 | 1291 | 2325 | 2967 | 4254 | 5922 |

| Seminars/Workshops | 29 | 192 | 238 | 328 | 334 | 532 | 587 | 747 |

| Computer Games | – | 13 | 34 | 53 | * | 331 | 1047 | 1942 |

| Card Games | 231 | 919 | 847 | 1579 | 1932 | 1958 | 2355 | 2183 |

| LARPs | 45 | 90 | 92 | 187 | 291 | 278 | 280 | 258 |

| True Dungeon | – | – | 413 | 553 | 620 | 812 | 813 | 825 |

| Isle of Misfit (Misc) | – | – | 28 | 140 | 67 | 258 | 378 | 767 |

| Spouse Activities | – | – | 31 | 88 | 90 | 236 | 266 | 346 |

| Anime Activities | – | – | 109 | 75 | 1 | 100 | 136 | 97 |

| Entertainment Events | – | – | 8 | 24 | 22 | 50 | 72 | 81 |

| Film Fest | – | – | 40 | 49 | 1 | 122 | 81 | 71 |

| Trade Day | – | – | – | 1 | 22 | 43 | 62 | 73 |

| Kids Activities | – | – | 16 | 41 | 79 | 127 | 78 | 81 |

| Notes. * No computer game event type is listed in the 2011 dataset. For information on the particulars of other event categories, see text below. | ||||||||

Although there is across-the-board-growth in the total number of events for all gaming event categories, further analysis shows different growth rates and changes in the relative importance of gaming event categories to the total number of Gen Con events (Table 8).

| Table 8. Gen Con Event Type Frequency Growth and Changes in Relative Importance: Indianapolis | ||||

| Category | 2003-2017 % Event Growth |

2003 Overall % of Events |

2017 Overall % of Events |

2003-2017 Overall % Change |

| RPG | 262% | 47.52% | 23.04% | -24.48% |

| Miniatures | 500% | 8.05 % | 6.47% | -1.58% |

| Board Games | 620% | 32.35% | 31.16% | -1.19% |

| LARPs | 473% | 1.76% | 1.35% | -0.41% |

| Film Fest | 710% | 0% | 0.37% | +0.37% |

| Trade Day | 730% | 0% | 0.38% | +0.38% |

| Entertainment Events | 810% | 0% | 0.42% | +0.42% |

| Kids Activities | 810% | 0% | 0.42% | +0.42% |

| Anime Activities | 970% | 0% | 0.51% | +0.51% |

| Spouse Activities | 3460% | 0% | 1.82% | +1.82% |

| Card Games | 845% | 9.08% | 11.48% | +2.40% |

| Seminars/Workshops | 2475% | 1.13% | 3.93% | +2.80% |

| Isle of Misfit (Misc) | 7670% | 0% | 4.03% | +4.03% |

| True Dungeon | 8250% | 0% | 4.34% | +4.34% |

| Computer Games | 194200% | 0% | 10.22% | +10.22% |

Nuance matters as much as raw numbers derived from the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset. The most striking takeaway from raw numbers for the 15-year period 2003-2017 is that RPG events plummet in relative frequency (-24.48%). At the same time, the numbers show that Computer Games increase their relative event share the most (+10.22%) followed by True Dungeon events (+4.34%) —a hybrid RPG/escape room/LARP/performance art immersive environment based on D&D settings, and more recently, Patrick Rothfuss’s The Kingkiller Chronicle fantasy fiction. As evidenced by the description of True Dungeon events, though, what appears to be a plummeting number of RPG events is better understood as the migration of tabletop RPGs in a transmedia world to other formats. For example, the most popular game systems in the Computer Games event category for 2017 were two Star Trek-inspired simulators—Artemis Bridge Simulator (248 events) and EmptyEpsilon (118 events)—where participants play roles in a cooperative tactical environment. Another roleplay simulator, Starship Horizons, featured in 79 events while other fantasy RPGs in a digital format included Diablo III (52 events) and World of Warcraft (52 events). In total, these five “computer games” are also 549 RPG events. For that matter, they are 549 transmedia events, as is every single True Dungeon event whether it is based on D&D settings or Patrick Rothfuss’s fantasy novels.

Gen Con event categories increasingly collapse into each other in the transmedia genre environment of 2017. For example, the board game with the most 2017 events was Dark Souls (Steamforged, 2017) based on the 2011 PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 RPG of the same name. Similarly, the card game with the most events was Legendary (Upper Deck, 2012) based on Marvel superheroes. To drive home the point, 2017 RPG events included among others Call of Cthulhu, Star Wars, Doctor Who, Star Trek Adventures, Dragon Age based on the computer game RPGs, and The Dresden Files based on the Jim Butcher novels.

Gen Con event categories likewise increasingly collapse boundaries between amusement and relaxation and extensive educational offerings. Accordingly, the historical record of embodied gamer cultures validates theoretical claims like Mia Consalvo’s 2009 notion of “gaming capital.” As summarized by MacCallum-Stewart and Trammell: “Gaming [c]apital is a way to capture the idea that belonging to game culture requires more than just playing games. More broadly, it’s about acquiring, creating, and sharing knowledge about games.” What sounds theoretically plausible can be verified with reference to lived Gen Con events. Thus, the word “taught” occurs 14,874 times in the description of 19,001 events for the year 2017 and the word “learn” occurs 2658 times. A glance at the 2017 miniatures game event category yields 116 out of 1230 events dedicated to teaching and learning about hobby aspects of these games like “Building Up Bases for Your Models” and “Painting Tricky Colors,” while another 787 out of 1114 miniatures game events contain the word “taught.”

Further exploration of the Best 50 Years in Gaming dataset can map additional levels of the lived experiences of gamer cultures inscribed in Gen Con events between 1967-2017. Meanwhile, this initial dataset analysis highlights two key characteristics of Gen Con and perhaps tabletop gaming conventions in general by looking at RPG activities: 1) a long-term and increasing transmedia presence, and 2) an overlooked educational function as a format to teach and learn about gaming. Although my approach using the Gen Con event corpus opens doors, more exploration of its 160,000+ events over 50 years will undoubtedly trace generative, alternative pathways through gamer and tabletop game industry histories. In the wider context of tourism studies, Gen Con can be productively located within a proliferation of recent work that investigates the economic and culture impacts of popular culture fandom.

–

The featured image is by Ben Jacobson (Kranar Drogin), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Cite This Essay: Baker, Neal. “50 Years of Gen Con Events: A Dataset Analysis.” Analog Game Studies 11, no. 2 (2024). https://analoggamestudies.org/2024/06/50-years-of-gen-con-events-a-dataset-analysis/. (PDF)

–

Neal Baker is a business librarian at Purdue University. His publications include scholarly anthology book chapters on tabletop RPG product lines, the LEGO Middle-earth product portfolio, and Star Trek: Voyager, as well as peer-reviewed articles on genre topics like Canadian science fiction, the Marvel Comics Alpha Flight series, and anime.