Trying to get rich in this indie RPG game is kind of a hopeless project anyway. I think we all have “day jobs?”

As part of a continuing series of interviews with independent game designers, Analog Game Studies seeks discussions on how design, communication, aesthetics, and social milieu feed into the games we play.

Ole Peder Ekelund Giæver can be said to be a regular border-crosser in terms of the role-playing medium. Originally from Tromsø, Norway, he spent his formative years in Ytre Enebakk, and moved to Oslo as a teenager. He went on to earn his bachelor’s degrees in history, philosophy and journalism. He currently works as a reporter for the online publication ABC Nyheter, helps run the weekly Norwegian larp podcast Live om laiv and contributes regularly to the Norwegian gaming zine Imagonem. A self-described “apolitical agnostic [with] culturally anarchist leanings,” Giæver has only recently come to the attention of role-playing gamers across the Atlantic as the co-author (with Martin Bull Gudmundsen) of surreal role-playing game Itras By (2012). The game takes place in a bizarre 1920s-era city belonging to the sleeping goddess Itra, whose dreams lurk behind both the city’s creation and its decay.

What marks Giæver’s work is a strong communicative framework for a fairly minuscule set of actual procedures that players must follow. In this respect, he champions the role that careful prose plays in delivering the content of a given role-playing game system and setting. Here we talk about Giæver’s experiences with the development of tabletop and live-action role-playing games in Norway, as well as the design and distribution factors surrounding the cult success of Itras By.

Evan Torner: Tell us a little bit about the evolution of the Nørwegian Style movement in role-playing design and your involvement in it.

Ole Peder Giæver: We had this web forum for Norwegian role-players running between 2003-2012. It’s still there, but no one uses it. We’re all on Facebook and everywhere else. Anyway, a hard core of 13-20 people were interested in game design, such that in 2004 Michael Stensen Sollien initiated a Game Chef-inspired competition that ran for several years. It did not have all the strictures with themes and ingredients, but the games were also supposed to be finished in a week. Over the years, the competition produced sketches and fairly half-assed results—some of which were mine—but also some pretty decent short games. Some were later polished and developed further.

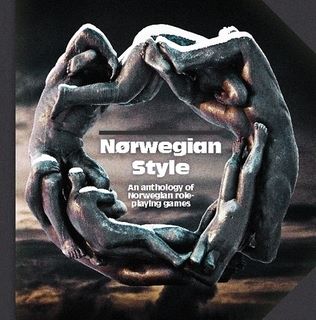

Around 2007, I think, there was an initiative to collect some of them (and games that hadn’t been part of the competition) in an English-language anthology, Nørwegian Style. It was published in 2009, and the blog by the same name was set up. The blog was also in English, and “Norwegian role-playing games in English” is the subtitle. The idea was to showcase some of our stuff to the international community. I’m not sure about sales, but I think it got a bit of buzz.

Matthijs Holter is, for all practical purposes, the main editor and contributor to the blog. But there have been others too over the years. It’s still a fairly eclectic mix of game sketches, blog-style meditations on various RPG-related subjects, some pretty complete games like Archipelago (2007, 2009), “role-playing poems,” playsets, scenarios and more. It is hard to say what is typical of these games. They are usually rules-light, and in communication with each other, “Nordic freeform” and the Anglo-American indie RPGs. Whilst doing their own thing. Whatever that is.

Matthijs had a blog post on this entitled “Stealing Like Ravens,” talking about that time when we basically agreed that we should feel free to use whatever cool concepts we all came up with:

“Back when I was designing Draug, and Ole Peder and Martin were designing Itras By, we were a bit worried for a while that since we were playtesting each others’ games and pitching ideas, we might end up having our brilliant designs stolen by the other party. What if I came up with something great for Draug, and they published my ideas in their game – before I could publish mine? We talked about it, and quickly reached the agreement “fuck it, let’s steal from each other, good luck to whoever publishes first”**. I think that little talk was an important step for our part of the Norwegian design community – we’re very open-source, and share our ideas and games freely. Itras By incorporates elements from many different writers, and continues to do so on the Itras By wiki.”

Not everyone in the scene necessarily agrees 100% with this open source philosophy. But that was our opinion back then. There had been Norwegian game designs prior to the competition, but few and far between. What had happened on the web forum was sort of an explosion, with people of similar interests finding each other and being inspired by each other, some doing various projects together. It was fun. Martin Bull Gudmundsen and I had started work on Itras By in 2001, finally publishing it in Norwegian in 2008. Tomas H.V. Mørkrid was avant-garde before any of us, of course, publishing weird little indie games as far back as 1989 and all through the 1990s, while the rest of us were still thinking Vampire: The Masquerade was ground-breaking stuff.

Some of the most interesting or artsy larp stuff coming out of Norway happened in parallel with this. There is a lot of overlap between the communities. For example, I have attended many larps, but have organized close to zero. Typical for Norway, the tabletop and live-action creators and creations have remained fairly separate. That seems to be different in Denmark, where Bifrost organizes both larpers and pen-and-paper group, and the huge Facebook-group “Danske Rollespillere” covers both formats and has over 4000+ members. These days, events and coordination seem to be coalescing a bit, with people finding each other and talking across borders. Obviously, I am a fan.

But I do not think it’s meaningful to talk about a “Nørwegian Style” movement/brand/scene in the singular. At least not in the sense that “jeepform” is a fairly organized “brand” where you know exactly which creators are in it and which games are canon because they put up a website that tells you that. Norwegian role-playing game designers are a small group— probably no more than 30, tops—who have done many things. Some—like my ever-productive friend Matthijs—still do, some might return to it, some have said their piece.

ET: What are, as you see it, the current trends in Norwegian game design, and how do you keep track of what is happening in the community?

OPG: There seems to be an interest in old school stuff and rules-light fantasy. On the Facebook-forum I help run, there were some recent initiatives to finally finish some games that have been in the works for years. One is Wanderer, a rules-light fantasy game. Some elements from the game were showcased in the Nørwegian Style-book. It’s fairly old school stuff. There’s also a project going on to translate the OSR game Basic Fantasy to Norwegian. I think it is good that people are talking again, creating stuff together, and that is partially thanks to the Facebook group creating a space for people to meet. Interesting, unforeseeable stuff will necessarily come of out of that.

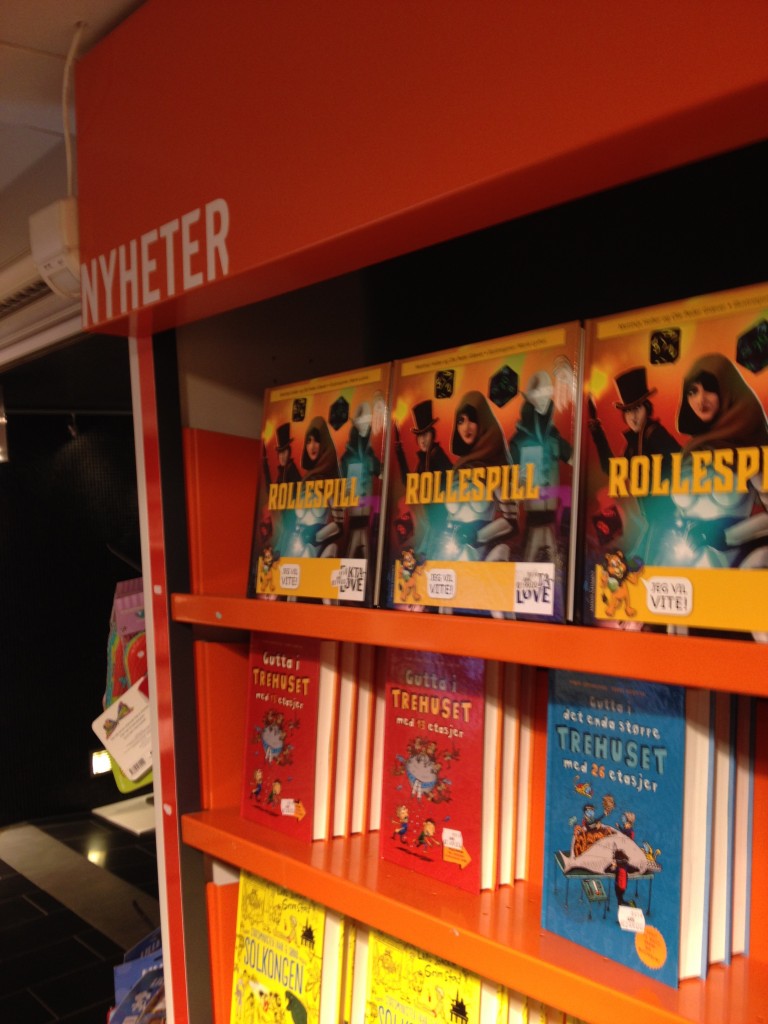

Matthijs still does a game for the blog now and then. I was contacted out of the blue by the National Museum of Arts to write a short collaborative storytelling game for an exposition they’re doing (about Lord of the Rings and Norse Sagas/Mythology). Last year, Matthijs and I published Rollespill, a book for kids about role-playing games, sort of an introductory factbook, via a traditional publishing house. It was purchased by all the libraries in the country. Who knows? Maybe it will recruit some souls.

Tomas has announced he will finish the second edition of Fabula, the fantasy game he initially released in 1999. He has often had interesting approaches to method and techniques, so I will check that out. Since 2013, I have been very interested in Nordic freeform, and especially the Fastaval scene in Denmark. I feel very at home there. It has tabletop roots, but with avant-garde and larpy sentiments. I’m hugely impressed with their scenario tradition, how seriously they take it and their will to experiment. But I don’t buy into it wholesale. I still want to do my own thing.

I plan to do a couple of larps, a long-form with Thomas Tollefsen, some esoteric-pervasive-personal-mindfuckery weirdness with the working title “Carnevale.” And a short larp with Ola Læhren that’s basically just for fun, about regional prejudice in Norway, where you have to play a character with a different dialect than your own and all the characters are regional stereotypes.

ET: Some describe Itras By as a “surreal” role-playing game, others as “urban fantasy.” How would you describe the game and its relationship to various genres and media?

OPG: Well, as Shakespeare said: “An ass by any other name would smell as sweet.”

I was 20 when we started working on Itras By. I’m not an artist, and haven’t studied art history. I read up on Breton’s manifesto, liked the commercial artist Dalí, and enjoyed some of the core ideas of the movement as far as I understood them: the language games, the focus on dreams, madness, and the “subconscious.” We tried to build something that would be sort of “intuitive” role-playing.

We mention several sources you could look into for further inspiration at the back of the book. Some of them are “intellectual ancestors.” Some of it stuff we’ve read and enjoyed. Some of it I haven’t—truth to be told—really seen. I never really got into Pratchett, for instance. I enjoyed Junkie, where Burroughs is writing in a realistic fashion about his experience as a drug addict, but couldn’t really grok Naked Lunch.

There are a lot of pop-cultural references in the game. Some are quite subtle, some are concepts lifted outright from other sources. There’s also a lot of my own and Martin’s subconscious shit and neuroses, I think we could say. Some of the dream-texts in the book—like the clowns staring at you through the restaurant windows or the woman with insects pouring out of her stomach—are actual dreams I’ve had. The core concepts, vibe of the game and the name of the city is from the automatic text in the back of the book that I wrote in Fall 2001.

The blog “Age of Ravens” had a very thorough review of the game where the author looked into how to label it with respect to others. The reviewer knows a whole lot more about the art movement and such terminology than myself. He suggests it could be termed “surrealism-light,” “new weird,” or “magical realism.” I think all of those sound cool, too.

ET: As a journalist, you take acts of communication very seriously. How did you communicate your expectations for player performance in Itras By?

OPG: I like the Forge maxim “System does matter,” but I’ve also always cared deeply for what is sometimes condescendingly referred to as “fluff text.” Player advice, setting descriptions, those kinds of things. There’s a lot of that in Itras By, and it takes up most of the text. We tried to be fairly pedagogic in explaining how to run the game, to make it approachable both for newbies and veterans who are used to other types of games. Some of it is in the form of “rules,” but most is framed as suggestions:

“Here are some ideas and effects you can try out (…)”

“Let the players add and describe elements from the popular culture of the city.”

“Give the players limited authority over chance (“we happen to meet on the street”).”

“Give the players whose characters are not present in the scene control over secondary characters who are.”

Of course, the game’s cards themselves actively distribute authorship in various specific ways. They help players get into the mindset of the game, gradually liberating them a bit from the structure of more traditional games. That was a big element to many of the earlier games from The Forge scene as well, redistributing GM-power through various formal rules and procedures. We’re doing some of the same, but in a less formalized fashion.

Martin came up with those small boxes admonishing the reader to “make the city her own” by making actual physical changes to the book: crossing out paragraphs you dislike, stapling in your own passages, taking notes in the book and things like that. Everyone seems to like those boxes, because they have this punk-rock kind of ethos. But I’ve rarely, if ever, heard of anyone who actually did it to their book. It’s too darn pretty.

When GMing, I usually try to follow our own advice in the book, I hope. But we all develop our idiosyncratic style over the years. I’ll point at players, instructing them to play secondary characters (NPC) so-and-so for the duration of the scene, cut scenes abruptly, leave them to talk amongst themselves if they’re in a good groove, try to ”say yes,” and give most player initiatives a chance. All of that good improv stuff. Letting loose, y’know? Trying to get away from that awful luggage of “the GM as God” who is somehow supposed to have planned everything about the background or even plotline in advance. Just accept it’s impossible, and try to work with the players instead of competing with them in some weird way. That’s how I like to play, anyway.

ET: Itras By has become something of a cult favorite on the global convention circuit. Once the game was ready for a national and international release, what did you do to keep it in the public eye?

OPG: Nationally: The book release was covered by around 15 different media outlets, everything from student radio to a big commercial radio station, anarchist rag to one of the largest online tabloids. The trick is to a) consider what kind of pitch will give meaning to the media given their profile and target audience, b) approach the right person, like journalists who’ve been friendly to this kind of material previously, or at least go to the culture section and not the news section. I also asked colleagues in various media for tips on to whom I should pitch it.

In the press release, I sold newsworthy elements such as Martin being kind of a reality documentary TV star at the time, Thore Hansen being a well-known illustrator—Martin and I grew up with fantasy and children’s books he’d illustrated—our receiving a fair amount of public and private grant money for the project, it being the first such release in a few years, etc.

Håken Lid helped us to set up a pretty decent Norwegian website, with some scenarios, a gallery, a section with press clippings, a wiki etc. A local gaming festival in Oslo agreed to feature the game as their “main theme” the year of the release (2008). We had some posters and flyers at hipster joints around town, there was a release at a bar frequented by bohemians. I toured all the three biggest conventions in the country that year to promote the game…

I wouldn’t really say all that publicity translated very directly to sales, though. At the time of writing, I think there are 425 copies of the physical Norwegian book in circulation (in 7 years). But that’s actually quite fair for being a sort of niche, Norwegian, self-published RPG. By comparison, the fact book Matthijs and I published professionally last year has sold at least 2,000 copies in just a year, but that’s mostly due to the library-thing I mentioned earlier.

Internationally speaking, I contacted a list of blogs and a few podcasts asking whether they wanted to review the game, sent out the PDFs or even bought them a physical copy of the book if they demanded that. It got a fair amount of reviews, article mentions and play reports, something like a dozen which I’m aware of.

But what has really boosted sales, more than doubled it, was the recent Indie RPG bundle. Prior to that, we’d sold 399 English books (print+PDF) since the English release in December 2012. With the bundle, we sold an additional 416 PDFs! It won’t make you rich, but such bundle deals are a great way of getting your book out there. Trying to get rich in this indie RPG game is kind of a hopeless project anyway. I think we all have “day jobs?”

I don’t speak Finnish (it’s a different language group altogether), so I haven’t done anything with promotion over there. I do believe it got a positive review in Helsingin Sanomat, which is one of the biggest newspapers. And an extremely negative review of the Finnish book, but in English on a blog.

It will soon be out in French with some additional material and new illustrations, German and Catalan(!). I think that’s pretty neat, that someone likes it enough to translate it. I was responsible for most of the English tradition, stupid errors, wordiness and all.

It’s also very cool that it actually gets played, as you mention. I Google it now and then, and I’m happy to see it’s still alive and kicking. That was a big part of the point of doing the project in the first place. To have people play it, hopefully have fun with it, and maybe even teach them about how role-playing can be done.

–

Feature Image by Thore Hansen.

–

Co-Editor-in-Chief of Analog Game Studies, Evan Torner, PhD (University of Massachusetts Amherst), is Assistant Professor of German Studies at the University of Cincinnati. His dissertation “The Race-Time Continuum: Race Projection in DEFA Genre Cinema” explores East German westerns, musicals and science fiction in terms of their representation of the Global South and its place in Marxist-Leninist historiography. This research has been supported by Fulbright and DEFA Foundation grants, as well as an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellowship at Grinnell College from 2013-14. His fields of expertise include East German genre cinema, German film history, critical race theory, and science fiction. His secondary fields of expertise include role-playing game studies, Nordic larp, cultural criticism, electronic music and second-language pedagogy. Torner has contributed to the field of game studies by way of his co-edited volume (with William J. White) entitled Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Role-Playing and Participatory Media (McFarland, 2012). He is also the co-organizer (with David Simkins) of the RPG Summit at DiGRA 2015 in Lüneburg, Germany. He can be reached at evan.torner <at> gmail.com.