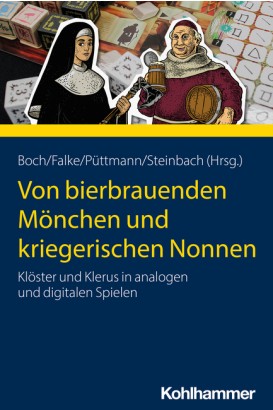

Lukas Boch, Anna Klara Falke, Yvonne Püttmann, Sebastian Steinbach, eds. Von bierbrauenden Mönchen und kriegerischen Nonnen: Klöster und Klerus in analogen und digitalen Spielen. Stuttgart: Kohlmann Verlag, 2023. 257 pages, Paperback w/ color illustrations. ISBN 978-3-17-042666-5

I admit that I attended graduate school after the collapse of postmodernism and “big theory” in the humanities. This meant that, rather than focus on sweeping questions like “What is language?” or “How do words have meaning?”, I was instead encouraged to (a) have a specific object or corpus to analyze, which I would (b) apply a specific method and (c) use evidence to arrive at a coherent, persuasive conclusion. Research focus was prized over sweeping arguments and theoretical sophistication, especially in communicating with all the possible stakeholders who might read a work. Personally, this has made me a fan of specific, topical research in humanities studies. In Film Studies, for example, we welcome highly focused studies such as an examination of mass-crime perpetrators in film or women’s hysteria in early cinema. We can absolutely hone in on a specific topic and then ask how that narrow field is treated by games as a medium, just like a movie or a comic book.

This all leads to the rhetorical question: Why can’t there be a book that pays close attention to how monks and nuns are represented in analog and digital games? The advantage of such studies is that subject-area experts can participate in Game Studies without needing to know the breadth and depth of all games relevant to their subfield, yet those who know both the subfield and a broader range of games are granted superpowers. Humanities knowledge dignifies the games, and the games re-enchant the humanities knowledge. Monks and nuns still exist in great numbers across a variety of different religious cultures, and the structures of game logic alongside the rules-based structures of organized religion cannot be denied. Games are thus another useful tool in a humanities scholar’s toolbox to apprehend underlying systems to be found in history, philosophy, language, and, yes, world religions.

The book in question here, whose title I translated as Of Beer-Brewing Monks and War-Like Nuns: Cloisters and Clergy in Analog and Digital Games, emerged from a 2022 museum exhibition staged at the Liesborn Abbey Museum in the small town of Wadersloh, Germany. A Game In Lab grant to the “Boardgame Historian” project created a space outside of any particular religious institution to have this conversation. Boch et al.’s scholarly independence is important, because the mostly former spaces of monks and nuns such as abbeys now become sites of their cultural interrogation. “Religiosity,” Yvonne Püttmann writes in her chapter in the book, “is increasingly vanishing from public spaces and becoming a private affair.” Analog games, themselves an expressive medium of the private sphere, now take on the mixed role of conveying public religious history through the messiness of play. While the book is undeniably, first and foremost, a conference proceedings for the sake of its funders, it also addresses what the journal of European Historical Game Studies and authors such as Jeremiah McCall explore in their publications: History as a “problem space,” in which players entertain various possible courses of action by historical agents. Re-framing history toward a “gamic mode” of understanding allows us to move from debating how accurate a game’s portrayal of historical material toward debating a game’s representational and system-mechanical strategies inherent in that portrayal. Games no longer have to exist under the suspicion of childish frivolity, but can take their rightful place as media objects in their own right.

Because of the museum studies context, the book is clear-eyed about the fact that analog games are material cultural products, themselves interventions into contemporary debates in physical form to be read, displayed, and/or played. Chapters by Norbert Köster and Anna Klara Falke reflect this very fact, with the former interrogating the site of the Wadersloh conference, Liesborn Abbey, with respect to the cultural practice of transforming former abbeys into museums, and the latter reflecting on issues with exhibiting games as artifacts, especially as the gameplay itself is usually the object of interest (and is, in turn, most destructive to the object itself). How do we put a game like Nuns on the Run (2018) on display as if it were an anthropological curiosity, when the gameplay reveals it as a deduction and chase game similar to 221B Baker St. (1975), something that those of us in analog game studies may be able to further discuss? Yvonne Püttmann’s contribution takes a look at pedagogical board games for religious education, eventually settling on Uwe Rosenberg’s Ora et Labora (2011) as an example of a board game that directly teaches Benedictine monastic regulations by way of example. Püttmann notes that historians have to take underlying rules systems seriously in their analyses, as a superficial description of a game’s visual representation is insufficient for an interpretation of the actual game dynamics. The game simulates rules that real monks follow, which also may be used to illuminate those rules to others.

Lukas Boch and Jonas Renz meanwhile use their respective chapters to offer substantive overviews as to how to assess monastic representation in board games and tabletop role-playing games. Boch’s chapter contains full-color illustrations of The King’s Abbey, a game which he contends “draws a picture of abbeys as blooming centers of economic activity that, at the same time, also form a bulwark against the dark, backwards external world.” Using monks as an example, Boch demonstrates for the reader just how one uses historical context and knowledge of game rules to mount a clear argument about game representation. Renz’s chapter meanwhile performs a similar trick for the German role-playing game The Dark Eye (Das Schwarze Auge). He points out the fact that the “medieval” world of such fantasy role-playing games seems to always bracket out the Christian-theological practices of those referenced times, de-coupling swords and sorcery from the epistemic foundations that make such fiction possible. This has the effect of a kind of double disavowal, in that western fantasy can neither shed its Christian assumptions nor fully engage with the specific doctrines of the medieval Catholic church.

Dungeons and Dragons, Magic: the Gathering, La Abadía del Crimen, Saga: Ära der Kreuzzüge, Ora et Labora, Dies Irae 795: the rest of the book leaps between gaming media, seemingly with glee. Video games, collectible card games, miniatures, established role-playing games, and others all receive treatment, as if to leave no stone unturned in seeking representations of medieval monks and nuns in games. The comprehensive media selection appears deliberate, a way of flexing the topic’s range and depth. Von bierbrauenden Mönchen und kriegerischen Nonnen accomplishes the main objective of any solid co-edited volume, which is to bring together different perspectives and objects of study so that the sum result is more than its parts. Monks and nuns emerge from these 250 pages as complex figures navigating economic uncertainty and religious doubt, somehow both on the cusp of mystery and adventure while also pursuing day-to-day routines that steadily improve their relationship with the divine. The editors seem genuinely enthusiastic about this material, an energy that propels both book and reader alike.

In an era after not only literary theory’s dominance but also the general funding of the humanities themselves, this quiet, co-edited volume maintains a resolute, humanistic position. From Uwe Rosenberg’s effusive comments about the math underlying his games to Eugen Pfister and Tobias Winnerling’s observation that Magic: the Gathering doesn’t care much for a game-mechanics profile for monk cards, this book simply asks its reader to delve into the realm of game design, agnostic of digital or analog, accurate or wildly fantastical. The field can be advanced through interdisciplinary, intermedial exploration, and here in full color. This German-language book may not end up in many hands among our English-speaking readership, but I assure you that it’s very much a scholarly accomplishment: an exploration of a topic so narrow, that it broadens our horizons to everything.

–––

Feature image of Cathedral of Monreale. Photo by Suzanne Plumette.

–––

Evan Torner, PhD (he/him) is an Associate Professor of German Studies and Niehoff Professor of Film & Media Studies at the University of Cincinnati, where he also serves as Undergraduate Director of German Studies and Director of the UC Game Lab. He is co-founder and an Editor of the journal Analog Game Studies and coordinating editor at the International Journal of Role-Playing. His fields of expertise include East German genre cinema, German film history, critical race theory, science fiction. role-playing game studies, Nordic larp, cultural criticism, and second-language pedagogy.