Tabletop role-playing gamers tend to have an affinity for their dice. From purchasing unique colors, fancy dice towers, and specialty dice bags, dice are a key material object in a genre whose vast majority of published systems require random number generators. Many a gamer has mentally tabulated probable outcomes of their rolls while playing or participated in theorycrafting. And good game designers have implemented appropriate mathematics into their system mechanics to support their theme. However, there is a lack of scholarship that provides an academic grounding on the subject. How do dice impact games statistically? Our goal is to fill this scholarly gap combining probability and tabletop role-playing games. To this end, our article conducts a comparative analysis of the combat effectiveness of beginning characters in a variety of tabletop role-playing games against enemies they typically fight in order to provide a mathematical basis for system comparison. Many players may not be familiar with the basics of probability making likely outcomes within TTRPGs seemingly unpredictable. Yet, as our comparison shows, the underlying mathematical system showcased via probabilities can fundamentally alter the play experience and its narrative possibilities, particularly in combat.

Our article constructs reasonably well-balanced starting characters across several TTRPG systems and analyzes their relative ability to succeed at attacking in combat in order to show the mathematical impact of different rules across game systems. But before getting into this aspect, we bridge the gap between mechanics and storytelling via critical successes to showcase this interesting duality within TTRPGs. We first orient the reader with the mathematical probability of critical successes and critical failures in several different tabletop game systems. For critical rolls, we examine D&D 5th Edition, Cyberpunk, Deadlands, and Shadowrun. Then we compare the likelihood of a low-level, combat-oriented character successfully striking their opponent across different systems. Our in-depth analysis includes D&D, Deadlands, and Sword Chronicle. This analysis can help designers and players be more aware of their to-hit probabilities and how these percentages change based on the gaming system that they are running. Games are rule bound systems and the random number generators selected for a TTRPG system and the parameters placed around those generators have a significant impact on the player experience. As useful as this information can be, it is surprising that probability in TTRPG systems has not been more critically studied and published. We roll out our research to highlight the dice on the table and the game system mechanics governing those dice.

Literature Review

Before we begin our review of the scholarly literature, we want to acknowledge all of the fans who have spent time crunching numbers. We agree with Evan Torner that role-playing game theorizing is all inclusive and “can be and is done by anyone: critics and scholars but also players, game masters, and designers.” Many label this “theorycrafting,” which is the analysis of game systems for optimization and emerged from massively multiplayer online RPG (MMORPG) players. We see this RPG theorizing in online forums, blogs, and fan zines. As academics, we also understand the need for peer-reviewed publications to provide foundational research in a field. While most theorycraft focuses on one game or one system, a key contribution we make with our article is to illustrate how systems compare based on their mathematical model of dice usage.

As a specialty field in mathematics, probability is extensively covered in terms of dice games, card games, sports, and puzzles, which all provide ready-made and easily accessible examples. In The Mathematics of Games, John D. Beasley writes, “if the playing of games is a natural instinct of all humans, the analysis of games is just as natural an instinct of mathematicians,” but this instinct seems to largely exclude TTRPGs in favor of traditional games, like chess and poker, and even sports, like golf and baseball. On the flip side, for a subsection of general tabletop games only formalized in the mid-1970s, TTRPGs have been discussed from a myriad of perspectives, but this has not included extensive mathematical analysis in the academic realm.

In TTRPG history texts, such as the bibliographic Heroic Worlds by Lawrence Schick and the historiographic series by Shannon Appelcline, it is not surprising that mathematical probability would not be included in the scope of their work. Similar assumptions apply with the impressive range of RPG books that focus on rhetoric and narrative, cultural influences of the genre, performance art, mediated or actual play, and social aspects of community and identity.

Outside of the history of the genre, the majority of published TTRPG texts analyze the genre or the culture surrounding a specific game from a humanities or social science lens, primarily within the academic disciplines of English, sociology, psychology, communications, or theatre, or from an educational stance with a focus on pedagogy. In the seminal edited collection Role-playing Game Studies, a myriad of perspectives are brought together in one text described as the “Disciplines of RPG Studies,” including: Science and Technology Studies, Designer and fan theorizing, Game design, Literary Studies, Economics, Communication, Sociology, Performance Studies, Education, and Psychology. The editors write that “Any additional number of disciplines could have been brought to bear upon RPGs — art history or moral philosophy come readily to mind. But we highlight those disciplines that have already produced significant work on RPGs.” It is for this reason that we assume mathematics is not included since there is not significant scholarly work in the field, and we want to be a player in rectifying that dearth.

Some sources briefly mention mathematics, mostly in passing. In an early ethnographic study, sociologist Gary Alan Fine has a detailed section on dice in fantasy role-playing games, but other than one mention that “the dice reflect the laws of probability” he spends most of his discussion dealing with players’ superstitions regarding their dice and dice rolling skills, a topic most of us that play can easily relate to. Mathematician Marcus du Sautoy includes a D&D chapter in his recent monograph that is subtitled “A Mathematician Unlocks the Secrets of the World’s Greatest Games,” but he does not discuss probability in that chapter. He references the polyhedral dice set as Platonic solids that he recognizes from studying Greek mathematics but spends more time on psychology and moral dilemmas that can manifest viz-a-viz the social nature of storytelling in a campaign in D&D, a game he acknowledges to only playing once. Similarly, in the edited collection The Bones: Us and Our Dice, their marketing blurb clearly indicates that this it not “about percentiles and probabilities,” but rather the emotional connection players feel when a narrative outcome is triggered because of a dice roll. However, one chapter by game designer Jason L. Blair does give rudimentary probabilities in his argument for why game designers should use six-sided dice as opposed to other die types such as the d4 or d10.

Even in books dedicated to introducing players, and specifically future GMs, to the industry with practical advice, mathematical probability is largely absent. In his very accessible introduction to TTRPGs in The Fantasy Roleplaying Gamer’s Bible, industry veteran Sean Patrick Fannon only discusses math in TTRPGs in an appendix where he includes the term “number-crunching.” He defines it as a “quirky term that refers to the mathematical elements of the game. The process of figuring stats and die rolls against one another…”

Sometimes players who are attuned to numbers are said to be roll-playing. In his non-mathematical analysis on the role of dice in TTRPGs, Joris Dormans defines this term to mean, “If the rules become too complicated, too cumbersome or if dice rolling becomes a goal in itself the game might change from a role-playing game into a ‘roll-playing’ game.” However Fannon acknowledges that this is a “derogatory term.” The next closest mention to probability in Fannon’s Bible comes in a discussion of dice, specifically d6, when he states that “Simply put, they generate a random number between ‘1’ and ‘6’.” He provides practical advice to new GMs and people wanting to get into the hobby, as well as a great review of the published games available, but the mathematics in TTRPGs is not included. In fact, he also downplays this portion of the gaming experience: “There are times when the game and the story are better served by just going with the flow and not bogging down in mechanics and numbers.” Based on our own gaming experience, this is sometimes true, but it does not account for the general lack of mathematical analysis in the larger critical discussion of TTRPGs.

The combination of math and games with the specific intersection of probability within the genre of tabletop role-playing games has not received critical attention except in a few rare cases. One mention is as a single example in a larger argument on game mechanics supporting the genre and setting of a tabletop role-playing game. In Primer for Gamemasters, game designer, publisher, and passionate GM Alexander Macris includes one example of the probability of certain roles. He states:

For instance, Cyberpunk 2020’s Interlock System offers a 10% chance for any given roll to be a critical success and a 10% chance for it to be a critical failure. Cyberpunk 2020 therefore implies a world where any punk can get lucky, and even the best of the best are eventually going to bite it due to bad luck.

Macris’ focus is on rule-sets in general, not just dice mechanics. For instance he uses Classic Traveller and its “fascinating character generation system” as another example of how the rules reinforce the structure of the world. We completely agree that a game system should align and support the genre and setting, but how do we know that it does if a key mechanic in TTRPGs, the probability of certain dice rolls within the system, has not been more thoroughly analyzed?

A book chapter in Mathematics in Popular Culture focuses on mathematical modeling as it applies to TTRPGs. Mathematician Kris Green acknowledges the use of probability, including cards and the bell curve generated by rolling multiple dice, but does not focus extensively on the actual mathematics within a particular game system. He states: “The outcome of each action has a different likelihood, or probability of occurrence; relevant abilities… influence the probability of a character being successful in a particular attempted action.” His focus goes beyond character creation and combat outcomes to laying out towns and designing economies, and his larger argument is a call to action to combine mathematics and TTRPGs for their pedagogical value via mathematical modeling.

We want to build off of the rare cases of proper mathematical discussion within the published literature that Macris and Green provide and develop it further with comparative analysis of modern game systems.

Methodology and Scope

For the first comparative analysis section, we examine the best and worst rolls possible for various systems, including: Dungeons & Dragons, Cyberpunk, Deadlands, and Shadowrun. We chose these well-known games because critical hits, fumbles, etc., are all strictly determined by the results of the dice being rolled, and are completely independent of any kind of actual target numbers. This means that they may come about from any attack roll. Worth mentioning now is that critical failures (missing a target number by 5 or more) do exist in Sword Chronicle, a text we address later, but we opted not to include it in this section because critical failures may not always have a chance to occur. For instance, it is impossible to roll a 3 when finding the sum of 4d6.

The second section will go into more depth and analyze attack results of beginning characters across multiple TTRPG systems against what we consider appropriate opponents. This comparison will be achieved through statistical modeling of attack roll probabilities generated with dice and will involve a variety of mathematical models based on the systems being considered. For this, we compare Dungeons & Dragons, Deadlands, and Sword Chronicle. We chose these games based on their systems’ relative distinctiveness to illustrate the fascinating mathematics behind their respective mechanics.

In this article we will focus specifically on probabilities of various outcomes. For example: If a combination of dice results yields 48 total distinct outcomes and 20 of those represent outcomes that achieve a goal, we will state this as a probability of 20/48. We deliberately avoid reducing fractions so that it is apparent where the results come from. We may also go on to simplify the above fraction by rounding to a probability of .417, which is 41.7 percent. Care must be taken when using the terms probabilities, odds, and percentages, since they are not mathematically interchangeable. And, mathematical probability is different from the theoretical concept of uncertainty.

Section One: Critical Hits and Misses

For an introductory exercise, before delving into more specific comparisons, let’s take a look at a gamer’s ultimate positive and negative roll — a critical success or critical failure. These rolls usually come in the form of rolling the highest or lowest possible number on some or all of the system’s random number generators and have various names like critical hit for a positive result or automatic miss, botch, or fumble for a negative result. This is why in D&D you will hear euphoric exclamations of “I rolled a nat 20!” and looks of despair while playing Deadlands when snake eyes are rolled. In some systems, these rolls are easier to achieve than in others. For critical rolls, we examine D&D 5th Edition, Cyberpunk, Deadlands, and Shadowrun.

The first game we will analyze is Dungeons & Dragons, 5th Edition, whose mechanics are similar to previous editions. When a 20 is rolled on a d20 attack roll in D&D, a critical hit is scored. Usually this means extra damage or some other beneficial effect. Since D&D uses a d20 for attacks, that means that the chances of rolling a critical hit on a standard roll is 1/20 (5 percent). Of particular note is that this percentage chance stays the same regardless of any modifiers due to experience level or equipment, as indicated by the rules. There are a few instances in which a player may score a critical hit on less than a 20, but these are very rare.

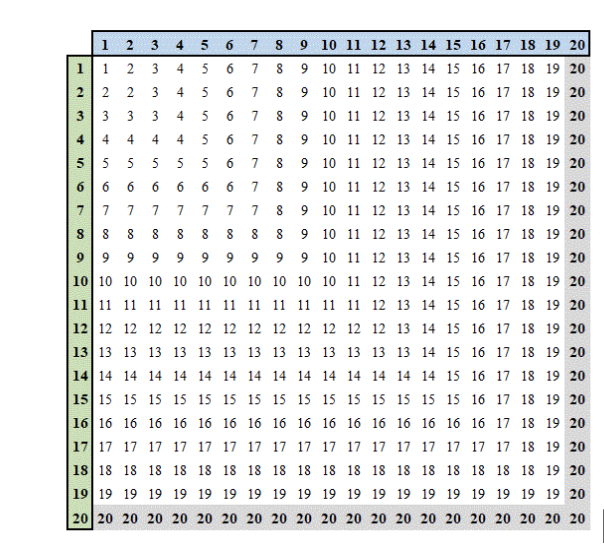

One of the exceptions to the 5 percent chance of rolling a critical hit is when a player attacks with advantage, a benefit that can be bestowed by anything from a spell to a racial feature. When attacking with advantage, a player rolls 2d20 and takes the higher of the two numbers. Figure 1 shows the potential outcomes when attacking with advantage in D&D.

Figure 1. The green and blue boxes represent the rolls on the 20-sided dice when attacking with advantage, while the gray boxes represent critical hits.

Tallying these results shows that attacking with advantage gives a 39/400 (or 9.75 percent) chance of a critical success. So players take note— attacking with advantage almost doubles your chances of a critical hit from 5 percent to 9.75 percent. (Also, watch out for kobolds!)

Although D&D does not use the terminology ‘critical failure’ when rolling a 1, it still provides rules for an epic whiff: “If the d20 roll for an attack is a 1, the attack misses regardless of any modifiers or the target’s [armor class] AC.” When performing a normal attack roll, the probability of an automatic miss is the same as for a critical success, or 1/20 (5 percent) for each. When rolling at disadvantage (rolling 2d20 and taking the lower of the 2 results), the probability of rolling a 1 is identical to the probability of rolling a 20 when rolling at advantage, that is 39/400 (9.75 percent).

The next game we will detail in this section is Cyberpunk (commonly called Cyberpunk 2020 for the edition we are referencing). Cyberpunk uses a standard d10 to make rolls. According to the game, “On a natural roll of 10, you have had a critical success. Roll an additional 1D10 and add it to your original roll.” In Cyberpunk, that means that a player has a 1/10 (10 percent) chance of rolling a critical success. On the other hand, “On a natural die roll of 1, you have fumbled. You must roll an additional 1D10 and check the result against the Fumble Table… to see what happens.” Therefore, the chance of rolling a fumble is also 1/10 (10 percent). Just as with D&D, these probabilities remain constant, and are independent of experience gained.

The third game we will discuss is Deadlands, based on the Savage Worlds Adventure Edition. When making a trait roll in Deadlands, a player character (called a Wild Card) rolls 2 dice and takes the higher of the 2 numbers. (There are additional mechanics involved, but these will be described later.) One of these dice is a trait die that is generally a d4, d6, d8, d10, or d12; while the other is a Wild Die that is almost always a d6. In the Savage Worlds system, “A Critical Failure occurs when a Wild Card rolls a 1 on both the skill die and Wild Die of a Trait roll. The attempt automatically fails and something bad happens” That means that the probability of rolling a critical failure is 1 over the product of the numbers of sides on the 2 dice being rolled. For example, rolling a d4 trait die with the d6 Wild Die has a 1/24 (or 4.2 percent) chance of resulting in a Critical Failure. When rolling a d12 trait die together with the d6 Wild Die, a player only has a 1/72 (or 1.4 percent) chance of a Critical Failure. An extremely consequential result of this system is that unlike the chances of rolling a critical hit in D&D or Cyberpunk, a character’s chances of rolling a Critical Failure in Deadlands change as they improve. Extraordinary successful attack rolls in Deadlands are called hits with raises. Raises are based on target numbers and not automatically determined by the numbers shown on the dice, and they will be addressed later in this article.

The last game in this section is Shadowrun, Sixth World Edition. Players in Shadowrun roll a collection of 6-sided dice and evaluate each die individually. These dice pools can sometimes be quite large. In Shadowrun, “If more than half of the dice that you roll on a test are 1s, you have rolled a glitch. If you rolled a glitch without a single hit [a 5 or 6] on the test, you have rolled a critical glitch” Interestingly, a glitch does not necessarily mean failure, though a critical glitch obviously does. It may then seem like the more experienced you are, and therefore the more dice you generally roll, the less likely you are to roll a glitch or critical glitch. However, the mathematics behind this can be counter-intuitive. For instance, a player has a 1/6 (16.7 percent) chance of not just glitching, but critically glitching, when rolling 1d6. When rolling 2d6, there is only a 1/36 (2.8 percent) chance of glitching since both dice must land on 1s. A glitch on a 2d6 also implies a critical glitch. Rolling 3d6 is where things get interesting. Even though more dice are involved, rolling two 1s still results in a glitch. The chances of this occurring are 16/216 (7.4 percent). Ten of those 16 glitches will be critical glitches (4.6 percent). Looking at it another way, since four 1s are required to glitch on 6d6 and 7d6, rolling more dice gives you a better chance of rolling those 1s. This will always be true for any even number of dice and the odd number immediately after it. Although glitches and critical glitches exist in this edition of Shadowrun, there are no rules for critical successes.

The previous three games all have prescribed effects or tables that the Dungeon Master, Marshall, etc., should consult when these rolls occur. Shadowrun, on the other hand, has an entire page dedicated to recommended results of glitches and critical glitches, and encourages the Gamemaster to choose an appropriate outcome. The suggestions for glitches range from “Turn your ankle wrong” to “brain fart” Critical glitches may have much more serious implications, including “Gun explodes! A flying piece takes out your eye.”

One of the reasons we decided to briefly discuss criticals, fumbles, and glitches is to not only introduce how we will analyze the mathematics behind various systems, but to show that achieving these types of rolls can have both a dramatic narrative and mechanical impact when playing these games. Rolling a critical hit in D&D can have a range of effects including extra damage, potentially severing a limb, or even decapitation from a vorpal sword. While using an infernal item, a critical failure in Deadlands might result in a rocket pack exploding or armor catching fire. A critical failure for a mad scientist in Deadlands can even assist them on the railroad track to insanity. Rolling a fumble in Cyberpunk prompts another roll and consultation with the fumble table. This may have no additional effect, cause a character to accidentally wound another party member, or even shoot themself. This narrative effect is in fact why we chose to include this version of Cyberpunk, because in the most recent edition, commonly called Cyberpunk Red to distinguish it, fumbles instead impose a purely numerical penalty that simply renders a lower test result. Figure 2 shows a comparative snapshot of the critical rolls for each system.

|

Percentage chance of getting the… |

||

|

System |

worst roll possible: |

best roll possible: |

|

Dungeons & Dragons (normal attack) |

5% (automatic miss) |

5% (critical hit) |

|

Dungeons & Dragons (attack with advantage) |

.25% (automatic miss) |

9.75% (critical hit) |

|

Dungeons & Dragons (attack with disadvantage) |

9.75% (automatic miss) |

.25% (critical hit) |

|

Cyberpunk |

10% (fumble) |

10% (critical success) |

|

Deadlands |

1.4% to 4.2% (critical failure) |

varies by target number (hit with a raise) |

|

Shadowrun |

varies by dice pool (glitch/critical glitch) |

N/A |

Figure 2. A summary of the percentage chances of achieving an outstanding success or failure based on the game system.

Section Two: Comparing Characters Across Systems

We will now compare starting characters across three TTRPGs—Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition, Deadlands, and Sword Chronicle—and analyze the probability that they will hit what is considered an appropriate opponent in that system. For each game system, we briefly cover character generation and essential elements of combat. Although we fully understand that characters for these games can be built in a number of ways, we built relatively balanced characters, even though they are designed as fighters. We acknowledge that a min-maxed character will statistically perform better. This is where online fans have often excelled in crunching numbers for gaming systems. Dedicated players have spent countless hours coming up with the most optimal build for a character. But we want to pull back the curtain and show several systems for a comparison to illustrate the most basic role of mathematical probability in the TTRPG game design.

Attack Rolls in Dungeons & Dragons

D&D has been around in one form or another for 50 years. Not enough can be said about how it has both influenced and dominated the tabletop role-playing game industry over this period of time. It is therefore fitting that we begin our analysis of attack rolls with the 5th edition of D&D. Before delving too much into the probabilities of success when attacking, we will first provide a brief overview of character generation and how combat works.

Character design in the 5th edition of D&D provides a number of options that players must navigate through. Three of the most important decisions that are made during character generation involve selecting a race, choosing a class, and assigning attribute points. Possible choices for race include humans, elves, dwarves, and many more. There are several classes including fighter, cleric, and warlock, among others, from which to choose. Players must also select a subclass and background. As characters earn experience, they gain levels, class features, and better equipment. High level parties in D&D are forces to be reckoned with.

To build what we consider a typical 1st level combat focused character, we first assign our attribute scores. Attribute points can be assigned via a few methods, including point buy. Assigned attribute scores generally range from 8 to 15 at character generation and have an associated modifier that adds +1 for every 2 full points above 10. An attribute score of 8 or 9 provides a -1 modifier to relevant rolls. Races also normally provide a bonus of 1 or 2 to some attributes. Standard humans receive a +1 modifier to every attribute. We consider a 16 or 17 Strength or Dexterity score fairly typical for a beginning combat-focused character’s most important attribute. Either of these scores provide a +3 bonus to the associated attack and damage rolls. Melee attacks that use brute force would add the +3 Strength modifier to both attack and damage rolls, while finesse or ranged attacks are normally adjusted by Dexterity.

In terms of class, this is actually not as important in our discussion as it may seem. At first level, all characters receive a +2 proficiency bonus to attack rolls, assuming that the player’s class provides training for their chosen weapon. Fighters, Barbarians, Paladins, and Rangers all receive weapon proficiencies in a wide variety of martial weapons, so any of these classes provides an equal basis for our discussion on attack rolls. While not proficient in as many weapons, Rogues will usually have a 16 or 17 Dexterity after character generation, so we can include them as well. We will therefore consider characters that have a total modifier to their attack rolls of +5.

One last thing to mention is the chance that a character will benefit from advantage on their attack rolls. Rogues may gain advantage on attack rolls due to being hidden. Certain racial features, like a kobold’s Pack Tactics ability, may also grant advantage. Barbarians gain rage at level two, potentially granting them advantage on attacks. We will thus include attacking at advantage in our discussion as a point of interest, to illustrate how utterly powerful it can be at virtually any level.

When attacking in D&D, players typically roll a d20 and add an attribute modifier and proficiency bonus to the roll. There may be additional numbers added to the attack roll if a Bless spell is in effect on the character, if a magic weapon is being used, or in a number of other situations. Since the latter situations are usually less applicable at 1st level, we will assume that a typical 1st level character rolls a 1d20+5 for attack rolls. We will briefly address the mathematical implications of a Bless spell, however.

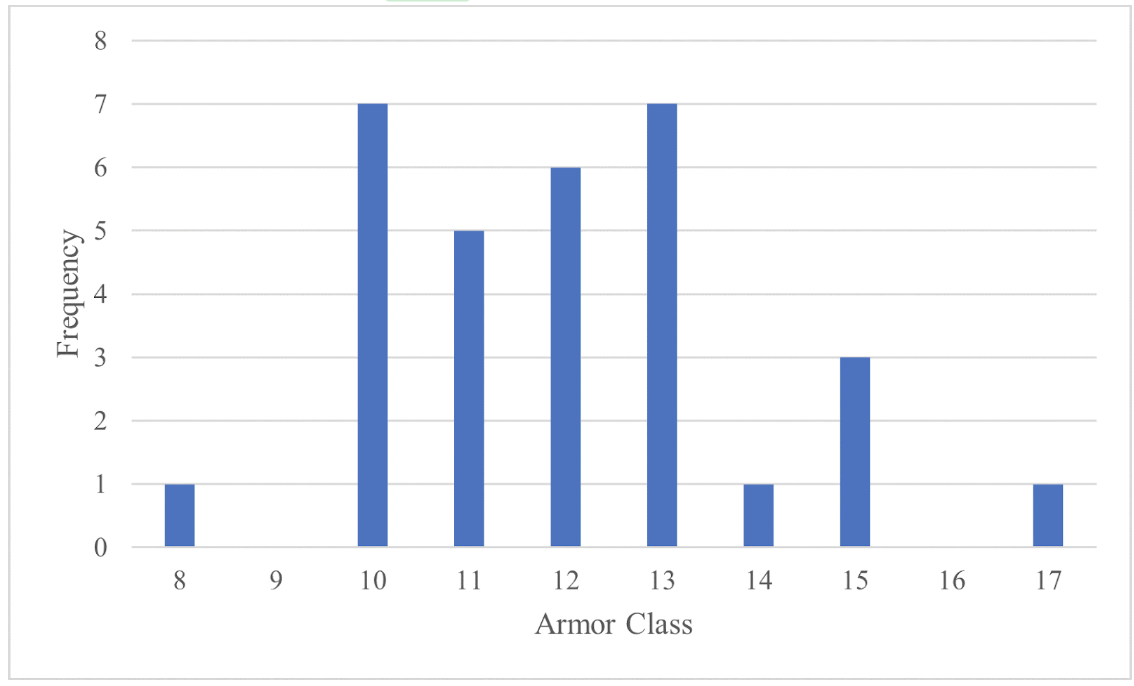

Once this roll is made, the sum is compared to the enemy’s Armor Class (AC). If the attack roll equals or exceeds the AC, then the attack hits. As noted previously, a d20 roll of 20 is a critical hit and automatically hits no matter what the target number. To keep our comparison across gaming systems as consistent as possible, we will assume that a character is attacking a relatively weak opponent. A suitable challenge for a single 1st level character is an enemy with a Challenge Rating (CR) of 1/4. Using CRs is a simple method of calculating an appropriate challenge for player characters. To arrive at a typical AC, we looked at 32 different CR 1/4 creatures from a variety of source material. The corresponding ACs for these creatures ranged from 8 to 17, with a mean of 11.8, a median of 12, and modes of 10 and 13. The distribution of these AC values can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Frequencies of Armor Classes of a sampling of CR 1/4 creatures in D&D.

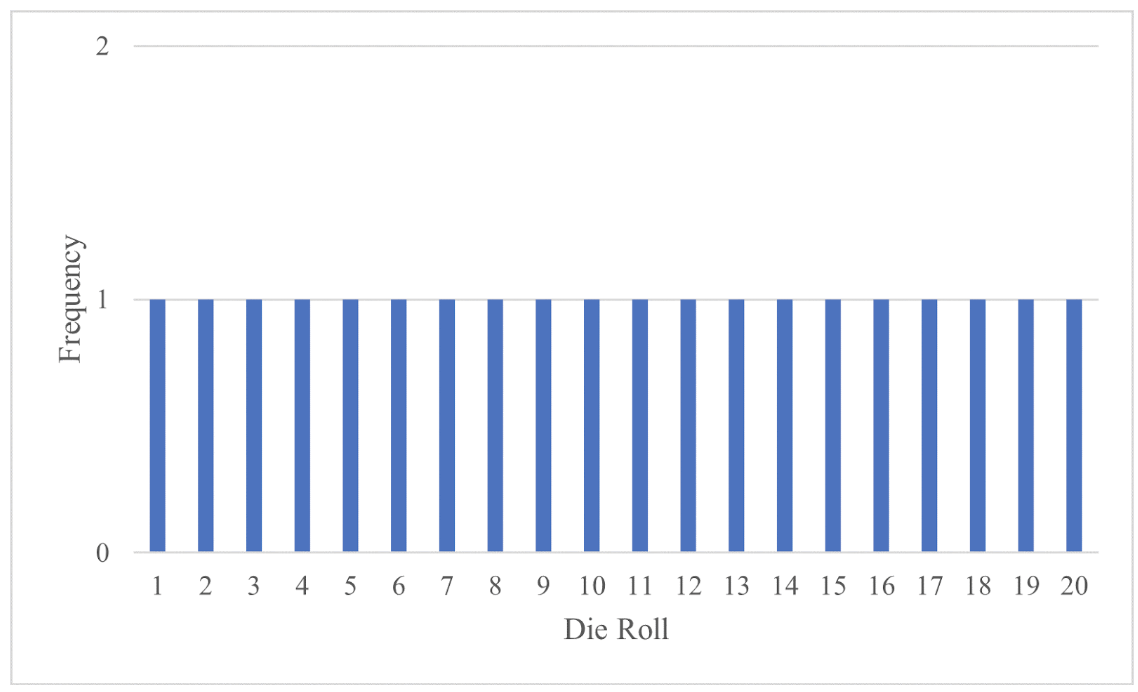

Based on this set of data, we will use 12 as our initial target number for attack rolls. With a modifier of +5, that means that a player must roll at least a 7 on the d20 to hit. When rolling a d20, each outcome from 1 to 20 is equally likely, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The distribution of outcomes when rolling 1d20.

While simple, this graph is included to visually show the stark contrast with Figure 5, below. We include these charts to illustrate the various types of distributions that dice can have. We want to clearly show this fundamental math because in our research the few game focused articles or books that did include probabilities frequently had errors such as confusing permutations with combinations or that odds and probability are interchangeable terms.

In summary, a 1st level character will have a 14/20 (70 percent) chance to hit an AC of 12. A roll of 1 to 6 will miss, so there is a 6/20 probability (30 percent) of failure. Although we used 12 as our target AC, for each point below 12, the percent chance to hit increases by 5 percent. The same character would have an 80 percent chance to hit an AC of 10. Likewise, a Bless spell that adds a d4 to the attack roll would increase the chances of hitting by 5 percent times the result on the d4.

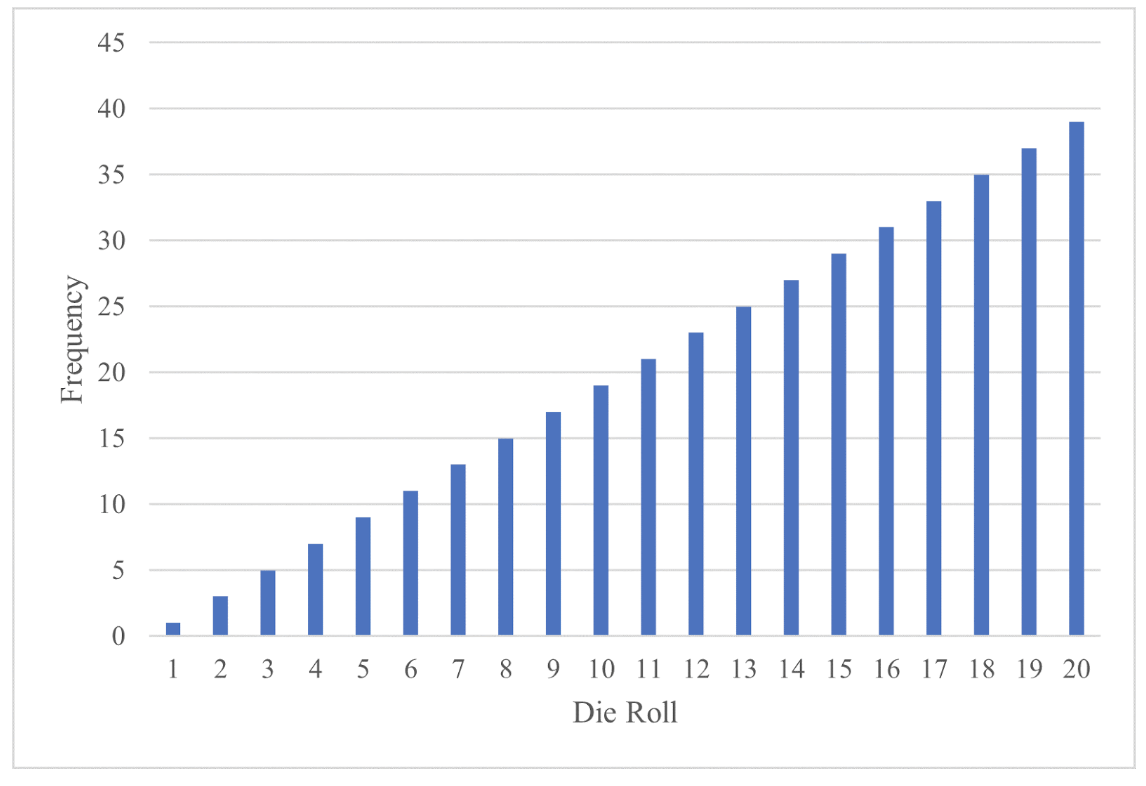

Now we will consider the same calculation but give the player character the benefit of attacking with advantage. Rolling 2d20, taking the higher of the 2 rolls, and adding the same +5 modifier generates a 364/400 probability (91 percent) of hitting an Armor Class of 12. Lowering the target’s AC to 10 gives a 384/400 probability (96 percent) of hitting. Since attacking with advantage uses a very different distribution, adding or subtracting 5 percent per point of AC does not work as it did when only rolling 1d20 to attack. For comparison, the distribution of the 400 outcomes when attacking with advantage can be seen on Figure 5.

Figure 5. The distribution of outcomes when rolling at advantage.

Before moving on to Deadlands, we conclude our results for D&D in Figure 6. This summarizes the percent chance of hitting a creature based on their AC, attacking normally or with advantage, with a +5 modifier.

|

Opponent’s Armor Class |

|||||||||

|

8 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

|

|

Attack |

90% |

80% |

75% |

70% |

65% |

60% |

55% |

50% |

45% |

|

Attack with Advantage |

99% |

96% |

93.8% |

91% |

87.8% |

84% |

79.8% |

75% |

69.8% |

|

Percent Increase with Advantage |

9% |

16% |

18.8% |

21% |

22.8% |

24% |

24.8% |

25% |

24.8% |

Figure 6. Typical percent chance to hit at 1st level, based on the target’s AC.

The largest difference between rolling with and without advantage (25 percent) occurs with a target number of 11 (AC 16 on Table 3). After AC 17, the percent increase in attacking with advantage continues to decline and resembles the pattern in Chart 4.

Even though he does not specifically address probability in his chapter dedicated to TTRPGs, Michael Tresca generically acknowledges it as good design: “Dungeons & Dragons [sic], with its levels and challenge ratings, is explicitly structured to provide the characters with a fighting chance.” For designers looking to emulate D&D, providing a mechanic similar to attacking with advantage (that is based on a sliding scale) can certainly make things more interesting and provide a benefit to players when they truly need it.

Attack Rolls in Deadlands

The second game we will discuss is Deadlands, a steampunk fantasy western set in the latter half of the 19th century. From Hucksters masking their spells with the use of playing cards to Mad Scientists designing otherworldly influenced devices, Deadlands has something for everyone. Deadlands has been around for roughly a quarter of a century. The mechanics have changed significantly over several iterations, but the use of playing cards and poker chips, in addition to dice, are hallmarks of the game. The most recent version of Deadlands is based on the Savage Worlds Adventurer’s Edition. Savage Worlds is a generic system, much like GURPS, that establishes a set of core rules on which to base a setting.

Characters in Deadlands have five attributes—Agility, Strength, Spirit, Smarts, and Vigor—all of which start at d4. There are also a number of skills, which collectively with attributes, are called traits. When creating a character, players have five additional points with which to raise attributes. Improving a trait that is at d4 will raise it to d6. After that, there are d8, d10, and d12 rankings. Higher level traits are attainable, but usually only by supernatural means or extreme levels of character experience. For skills, players receive a d4 for free in a few core skills, like Persuasion and Athletics, and then have twelve more points to distribute as they wish. Unlike attributes, skills start at nothing, so putting one point into a skill starts it at d4. A character may attempt a skill roll if they are untrained, but the default for this roll is 1d4-2. After deciding on their traits, players may also buy edges and hindrances for their characters. These run the gamut and include Loyal, Arcane Background, Addiction, Ambidextrous, Veteran of the Weird West, and even Grim Servant o’ Death. There are no class-based levels in the Savage Worlds system. If a character wants to be able to do something or do it well, they simply buy the relevant edge or raise the appropriate trait.

For our primary comparison, we will assume that a character built as a gunslinger or soldier will have a d8 in Shooting. A d8 Shooting skill means that a character will roll a d8 when shooting at someone. Raising Shooting to this level can be done without unbalancing the character significantly. It is possible to have a d10 or a d12 Shooting initially, but this may result in a character that is barely able to function in any other capacity. Two additional features of the Savage Worlds system are the Wild Die and exploding dice. Player Characters in Savage Worlds are called Wild Cards. Very important NPCs may also be Wild Cards. One of the benefits of a Wild Card is that when making a trait roll, players roll an additional Wild Die that is almost always a d6. They then take the higher of the two rolls between their trait die and the Wild Die. Additionally, when a die roll results in the maximum number possible, that die is re-rolled and the subsequent roll is added to the first. This is called Acing, or exploding. If the subsequent roll is also the maximum, the process is repeated. That means that it is theoretically possible, however statistically unlikely, to hit any target number with any trait level in Deadlands. This mechanic also appears in Dark Heresy and The Witcher TTRPGs, among others.

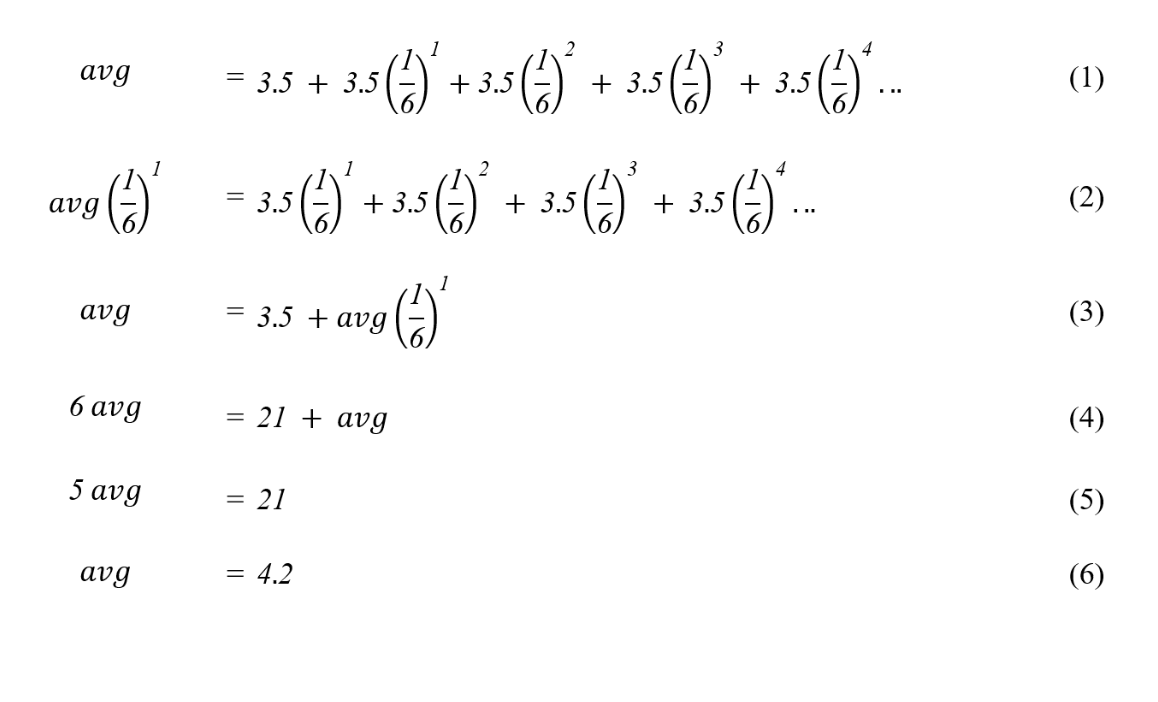

Before proceeding, we will address the implications of exploding dice and how to calculate the average (mean) result for these dice rolls. For most of the other systems addressed in this article, including D&D and Sword Chronicle, calculating an average die roll is fairly simple. To do so, add together all the numbers on the die and divide by the number of sides. Alternatively, add 1 to the maximum number and then divide by 2. For a d6 the mean is 3.5, a d8 has a mean of 4.5, and a d20 has a mean of 10.5. Exploding dice, on the other hand, are much more complicated to deal with. Calculating the mean for a d6 that can Ace actually generates a geometric series, as seen in Figure 7, also known as equation (1) below:

Figure 7. Deriving the mean for an exploding d6

Looking at the right-hand side of equation (1), the 3.5 is the mean result for a single d6. That same d6 has a 1/6 probability of Acing and adding another value with a mean of 3.5 to it; hence, the second term on the right side. The next roll would have an additional 1/6 chance of Acing, and so on. To derive equation (2) we multiply both sides of equation (1) by 1/6. To arrive at equation (3), we substitute all but the first term of the right side of equation (1) with the left side of equation (2). After that, simple algebra gives us a mean roll of 4.2 for our exploding d6. A similar calculation produces a mean roll of 5.14 for a d8 that can explode and 11.05 for an exploding d20.

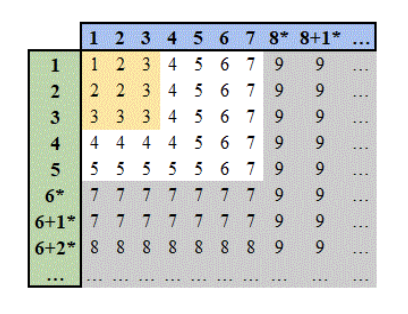

Moving on to the basics of combat in Deadlands, we will again base our calculations on a Wild Card with a Shooting skill of d8. There are a handful of modifiers that may impact this roll, such as the Trademark Weapon edge, the Dodge edge, size, range, or cover, but we will assume that none of these come into play here. In Deadlands, players draw from a deck of standard playing cards to determine their character’s initiative. If a player then takes the shooting action, they roll their Shooting skill die along with the Wild Die and take the higher of the two rolls. The standard target number when shooting someone is 4. Melee rolls have a target number of 2 plus half the opposing character’s Fighting die type.

Figure 8 shows the results of rolling a d6 Wild Die along with a d8 skill die. Numbers with an * are dice results that would Ace and produce results in the gray areas. Note that when rolling a d8, it is impossible to actually roll an 8, unless there are additional modifiers at play, since the die would explode.

Figure 8. The outcomes of rolling a (green) d6 and a (blue) d8, both of which can Ace, and taking the higher result. Values marked with an * indicate an Ace and re-roll.

Looking at the possible results for rolling these two dice, only the 1s, 2s, and 3s (indicated by the yellow boxes) would miss. Therefore, our shooter would have a 39/48 probability (81.25%) of hitting their target. Having discussed attacking in Savage Worlds, we will briefly mention the system’s equivalent of critical hits: raises. If an attack roll exceeds the target number by at least 4, the character hits with a raise and causes an extra d6 damage. In our example, the person shooting would have a 24.7 percent chance of hitting with a raise (rolling at least an 8) and causing extra damage. And who doesn’t want to cause more mayhem in the weird west?

Attack Rolls in Sword Chronicle

The last game we will detail in our system comparison is Sword Chronicle: Feudal Fantasy Roleplaying by Green Ronin Publishing. This game is meant to serve as a foundation for a fairly generic fantasy world with specific setting details left up to the players. What sets Sword Chronicle apart are the rules for kingdom building, in which players manage the house and lands of their characters. The most famous setting that utilized the Sword Chronicle rules was A Song of Ice and Fire.

Characters in Sword Chronicle have nineteen abilities—Agility, Athletics, Awareness, Cunning and Fighting, among others. The ranks for these normally range from 1 to about 7. Characters receive a certain number of Experience points (XP), determined by their age, at character generation. All abilities have a default starting score of 2. Players may then spend xp to raise them. With the permission of the Narrator, players may also lower a single ability to 1 to regain 50xp. Specific specialties for abilities may also be taken, such as the Long Blades focus under the Fighting ability. After that, characters receive a certain number of Destiny Points, some of which they may spend to buy benefits (extremely similar to edges in Deadlands). Players may also take drawbacks in exchange for extra Destiny Points. The amount of xp a character receives during character creation is inversely proportional to the number of Destiny Points they start with. As with Deadlands, there are no level-based classes in Sword Chronicle.

For the purposes of designing what we consider a typical fighter, we will assume a starting weapon skill of 4 with one specialization rank in their weapon of choice, for instance Long Blades. The character would then have Fighting 4D (Long Blades 1B). This combination is in fact identical to the Fighting and specialization rank of the Landless Knight, Assassin, and Guard in the Sample Narrator Characters section of the Sword Chronicle book. It is possible to have a higher score, but doing so would result in an unbalanced character, similar to starting with a d12 Shooting in Deadlands.

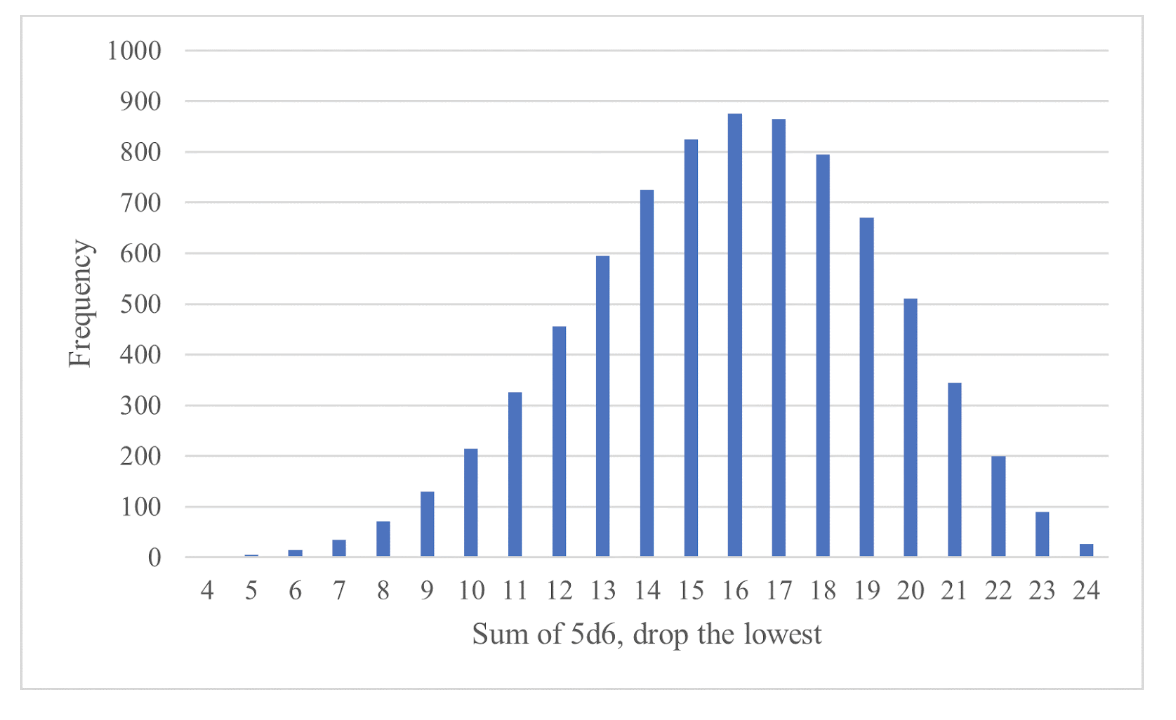

When making an attack roll in Sword Chronicle, a player rolls a number of 6-sided dice equal to the ability rank plus specialization dice, drops a number of the lowest dice equal to the specialization score, then finds the sum of the remaining dice. In our example, the player would roll 5 dice, drop the lowest die, and then find the sum of the remaining 4 dice. A player with 6 ranks in Fighting and 2 bonus dice in Axes would roll 8 dice, take away the 2 lowest, and then find the sum of the remaining 6 dice. The target number to hit in Sword Chronicle is equal to the target’s Agility + Athletics + Awareness + Defensive Bonus. The first three of these numbers are ability scores while the last is typically granted by a shield. Unlike D&D, armor in Sword Chronicle reduces damage after being hit; it does not make a character harder to hit. In analyzing the combat in this game, we will assume a target Combat Defense of 8. This is the same as the Combat Defense of a standard Bandit and Guard, 1 higher than the Landless Knight, and 1 lower than the Veteran Knight; again, all of which are found in the NPC section of the book. We will analyze the probability for rolling this target number as well as consider what would happen if the target was wielding a shield that grants a +4 Defensive Bonus. Figure 9 shows the distribution of this attack roll. If the character did not have a bonus die, this would in fact be a perfectly symmetric normal distribution.

Figure 9. The distribution for rolling 5d6, dropping the lowest die, and finding the sum of the remaining 4 dice.

Rolling against a Combat Defense of 8, a character will have a 7,720/7,776 probability (99.3 percent) of hitting their target with a Fighting of 4 and 1 bonus die. If the target was using a shield, raising its Combat Defense to 12, the same character would have a 6,979/7,776 probability (89.8 percent) of hitting. While these probabilities do seem extremely high, just because a character hits in Sword Chronicle does not mean they are guaranteed to cause any damage since armor reduces damage according to its rating. It is entirely possible that a weapon will only do 3 or 4 base damage against a character wearing chainmail with an Armor Rating of 5 or someone donning full plate that has a 10 Armor Rating. To compensate for this, damage is multiplied by an additional factor for every 5 full points by which the associated attack roll beats the target’s Combat Defense. In our example of an attack against someone with a Combat Defense of 8, rolling at least a 13 (83.9 percent chance) would double the damage, an 18 (33.9 percent chance) would triple the damage, and a 23 (1.5 percent chance) would cause quadruple damage. Indeed, if an enemy is wearing heavier armor, these rolls may be entirely necessary to inflict any harm at all.

Although Sword Chronicle is perhaps not as well known as D&D and Deadlands, we thought it an interesting comparison based on its dice pool mechanics. Though the previous two games use a different mechanic for attack rolls, they do use d6 dice pools (with distributions similar to Figure 9, but symmetric) to calculate damage effects from fireballs, firearms, dynamite, etc.

Conclusion

So, are you statistically more likely to be a better fighter in one role-playing game solely because of the mathematical system? Yes, you are! Here is a summary of our results based on what we consider a typical starting combat-oriented character:

|

Game System |

‘Critical Miss’ |

Chance to Hit |

‘Critical Hit’ |

||||

|

Dungeons & Dragons |

Target Armor Class |

||||||

|

type of attack: |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

|||

|

normal |

5% |

80% |

75% |

70% |

65% |

5% |

|

|

with advantage |

.25% |

96% |

93.8% |

91% |

87.8% |

9.75% |

|

|

Deadlands |

2.1% |

81.25% |

24.7% |

||||

|

Sword Chronicle |

opponent: |

(missing TN by at least 5) |

hit |

double damage |

triple damage |

quadruple damage |

|

|

no shield |

0% |

99.3% |

83.9% |

33.9% |

1.5% |

||

|

shield |

.7% |

89.8% |

45% |

4.1% |

0% |

||

Figure 10. An overall comparison of the three primary games discussed.

Based on this analysis, designers of these game systems in general have the same objective that a good GM does — they want their players to succeed overall but still sweat a little bit knowing that there is a chance they may not. As award winning game designer Jennell Jaquays writes, “Foes should seem unbeatable. The foes that the heroes must overcome should look overwhelming and the odds should seem impossible” One possible reason that probability has not been analyzed more critically is to keep the illusion of the game intact; maybe it is assumed one should not scrutinize the numbers too closely or a player might risk feeling a little less heroic. But for players, this data has clear implications: in D&D, get advantage and use the Bless spell; in Sword Chronicle, use a shield. But more importantly for both players and designers, understand that TTRPGs that use dice have an underlying mathematical system that plays into uncertainty but still maintain a probabilistically likely outcome. Hopefully this has lifted a designer’s metaphorical DM screen and revealed a little about the mathematical systems underlining some of our favorite game systems.

Cover image “dice” by Amy the Nurse CC-BY @ Flickr

Cathlena Martin, PhD, is Professor of Game Studies and Design at the University of Montevallo. Publication highlights include a co-authored book chapter in The Role-Playing Society on the influence of table-top role-playing games on board and card games, an article in the American Journal of Play on children’s literature’s role in the early history of role-playing games, and two games with critical essays in OneShot: A Journal of Critical Games and Play.

Benton Tyler, PhD, is a Professor of Mathematics at the University of Montevallo in Montevallo, Alabama. He

received his Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of Mississippi. His research interests and publications lie

primarily in the fields of combinatorics and game theory.