Steal Away Jordan is a game that asks players to take on the role of an African-American slave. When it was first released, it generated strong reactions, both positive and negative.Because it deals so explicitly with slavery in America, one reviewer wrote that Steal Away Jordan “received some attention for tackling a serious subject in a medium usually used for lighter entertainment.” While some praised it for tackling this issue, or for putting slaves (rather than white abolitionists) at the center of the narrative, the game also received critiques that it wasn’t a game at all. Even those who had not played the game expressed their opinions that a game about slavery could not be “fun.” Because not all games receive this caliber of critical attention, I interviewed its designer, Julia Bond Ellingboe, to see how she wrestled with America’s fraught relationship with racial politics as a designer.

For those readers who have not yet played the game, Steal Away Jordan: Stories from America’s Peculiar Institution is a tabletop role-playing game in which players tell the collective stories of enslaved people. Written in the spirit of neo-slave narratives like Margaret Walker’s Jubilee, Toni Morrison’s Beloved, and Octavia Butler’s Kindred, the game is set during the United States’ antebellum period. Each session focuses on the struggles of a group of slaves to achieve their secret goals. These range from large goals like killing the overseer, to smaller goals, such as keeping a family member from being sold away, learning to read in secret, or getting a pair of shoes. Players have to work together to achieve their goals, but the game also forces characters to make hard decisions about when to prioritize their own goals over the needs of other characters. Does one make a break for it during a moment of conflict or stand up for another slave as they are interrogated about missing goods?

As a frequent collaborator with Ellingboe in game design, I have always been curious about her reaction to Steal Away Jordan’s reception. In this interview she shares with me how her experience differs from that of other white, male game designers. She incisively relativizes debates about whether Steal Away Jordan is a game or an educational tool. This discussion helps to reveal several important boundaries in the RPG community including who can be a game designer, what kinds of role-playing games are acceptable, and what counts as a “fun” experience. This type of borderwork allows for policing without overt expressions of racism or sexism. It lets designers from marginalized groups know that they are only allowed into the community if they follow certain rules. As has become clear from discussions around diversifying games, there is a worry by the dominant majority (often white males) that new, diverse players, designers, or critics will “ruin” games. By policing the boundaries of “fun,” role-playing games, and game designers, the majority group also attempts to protect their hobby from the intrusion of new folks who want to open these boundaries.

As Julia’s first game, Steal Away Jordan shaped her future as a game designer in fundamental ways. At the same time, however, her experience serves to illuminate some important points about tokenism, marginalization, and intersectionality in the gaming community.

Katherine Castiello Jones: So tell us a little bit about your game Steal Away Jordan.

Julia Bond Ellingboe: Well, it was the first game I ever wrote. When I wrote it I hadn’t been role-playing for very long. Looking back on it now, I would say it is a very naive game.

When I was writing it, I was asking myself: “Who are the heroes?” As a new role-player, the fantasy stuff wasn’t that interesting for me. I wanted to try my hand at something different. And so it is a game about that. Discussions of slave life were very common in my family because my mother is a history professor and used to teach high-school history. My parents were also around during the Civil Rights era and so they cultivated an awareness of our roots. The game is a celebration of what kind of people are important enough to have games written about them.

KCJ: Can you give some more details about the game for people who may not have played it?

JBE: So one thing about how the game is played: you roll a lot of dice. If you stripped away the antebellum setting and the theme, the mechanics would be easy to use for some other thing. One thing I want to emphasize is that it’s a game. When Steal Away Jordan first came out, many people wanted to define it as a historical exercise. But it’s a game. It is a role-playing game. It is designed to be fun. It is full of epic, embellished stories. A lot of fantasy stories have these same elements. One thing I wanted to show in this game is that slaves had a lot more agency than is commonly recognized. In this sense, it is really a game about the triumph of the human spirit. The characters in it are working to achieve something against all odds, much like in other role-playing games.

You’re there to tell your story. It’s not meant to make people feel bad. So when people told me they would feel guilty if they played the game I have to say: maybe that’s what you’re bringing to the game, because that’s not what the game brings.

It is really interesting how the game works out statistically. The more dice you roll, the better the chance that you will fail. There are times in the game when you’re facing someone with many more dice than you, but there is still a potential to succeed. The Master can still fail.

KCJ: So when the game first game out how to you react to some of the initial responses?

JBE: It was my first game. So the positive responses made me really happy. I never expected the game to be perfect. I was honestly just glad people tried it.

As for the negative responses, at the time I was very defensive and hurt by them. The negative responses seemed to fall into two camps. First, there was a lot of critique of its production values. And yes, the production values of the game weren’t very good. It was basically an Ashcan. I did all of the design and layout work myself. I wasn’t familiar with the design software either, so I was learning as I did it. That being said, many other games with similarly bad production values are published without aesthetic critique. In hindsight, critiquing the production quality of games seems like a way to criticize the game without being a jerk.

The second camp of critiques were about how Steal Away Jordan wasn’t a game. People would say things like, “It’s more of an educational exercise.” And then they would say, “It’s just not my thing.” There was a really defensive quality to it. Like, the game is not your thing, that’s fine. But it was almost like they were saying: “Why couldn’t you make it my thing?”

Some people even said, “I’m afraid to play this game.” Those were the ones that really bothered me, because there are other games with difficult content that weren’t treated in the same way. Like, why are you trying to be so nice? Why do you have to prove it’s not your thing? Jason Morningstar’s game about child resistance fighters, Grey Ranks, came out around the same time. People said the same kinds of things, but not with the same tone of apology.

Some people said to me: “I’m afraid of getting it wrong.” There are a lot of assumptions that go into that statement. First, it assumes people are going to play a stereotype. It assumes that black people are so vastly different that you can’t understand their experience—these are the same people who can play an elf for days. I personally don’t know any slaves. I also don’t know any elves. But I can pretend. You’re always bringing yourself into the game, into your character. If you’ve ever wanted to accomplish something and the odds were against you, you can understand the experience of these characters. You may not know what it’s like to be whipped, but we play people inflicting violence on each other all the time in fantasy games. I’ve never heard someone say, “Well I can’t play this paladin, because I don’t really have an experience as a paladin, and I’m afraid of getting it wrong.” But there are actual black people out there, so it raises the question what do you think black people are? Aren’t they human beings?

KCJ: Can you talk a little bit about how your identity as an African American woman game designer influenced the response to Steal Away Jordan?

JBE: Well, at the time there were certainly other women and other African-American game designers. But there were a lot less of them in the “indie” scene. I think people responded to who I was when making the critiques. They would say things in their reviews like “but she’s a really nice person,” which you wouldn’t say about a male game designer. I started to prefer people that just canned the game, because that felt a lot more honest.

There’s this idea that in places like the South if you’re confronted with racism or sexism you know what it sounds like, but at other times and places racism and sexism are much more subtle. It is disguised with politeness.

At times I felt like this weird unicorn. Some people defended me by saying, she’s qualified to write this game because she’s African American. But, can women and African Americans only write their own experiences? I find that this same standard isn’t applied to white men.

KCJ: Where do you think some of the critiques that Steal Away Jordan is “not a game” came from? Why this boundary policing?

JBE: I think a lot of it comes from the subject matter. There is often an idea among gamers that a game has to be “fun.” The definition of “fun” is something that gets policed. There is an idea that games have to be fantastical. That a game shouldn’t make you think beyond what pleases your character.

People talk about pushing boundaries and going outside their comfort zones, but it is clear there are some boundaries people are not prepared to push. Some of these boundaries are good, like when someone doesn’t want to play a game that deals with rape. Unfortunately, some people claimed that Steal Away Jordan had a subject matter that could only appeal to certain people. I think that attitude has changed a lot in the last five years. You have a lot more games that address social themes finding a solid audience.

KCJ: How did has your experience with the response to Steal Away Jordan shaped your current and future game design?

JBE: When it comes to the games I’m designing now I’m much more interested in games that play with gender. I don’t really feel like talking about race any more. The reception of both me and the game was so racialized, I don’t want to go back to it.

I recently heard a piece on NPR about the first African-American woman in the National Wildlife Service. She said that people consider her a pioneer. Although I’m not a pioneer, I was one of the first and only in my circle of game designers. She said: “Being a pioneer is a really lonely place.”

Now that people of color and women game designers are better appreciated, but at the time I was in too much of a lonely place. . I still want to push buttons and push boundaries, but I want to do it in different ways. I want to write about things that are less visible when you meet me.

I write games that come from my heart and my psyche. And I would like to continue to do that, but for things that are not necessarily obvious. Like sexuality and gender.

When talking about womanhood one of the questions I ask is who do you include and who do you exclude? The idea of “ladyhood” wasn’t really available, and in many ways still isn’t available to African American women. Just look at the way that people talk about Serena Williams, in terms of her appearance and playing style. She is constantly being compared to a man, or described as masculine, both in positive and negative ways. As a tall African-American woman with a deep voice, that says something to me about how black women are perceived. There is still a different way people have of speaking to my womanness. And this is something I have also found with friends and family who are trans*, this denial of womanness.

KCJ: So why have you moved away from games that deal with race, but still feel comfortable writing games that explore themes of sexuality and gender?

JBE: Although I can find other women game designers in the scene, I see a scant few black designers. It’s hard to be the unicorn. In my day-to-day life I’m one of the only African Americans in my workplace. I unpack that in different ways, I don’t want to unpack that in my game design.

Right now, I am the only African American woman executive that my company has ever had. I deal with “only-ness” every single day. I don’t want to play it!

I also think there are other people who are more interested in pushing for racial inclusiveness in games. More power to them. I don’t want to be typecast. There’s more to me than my race. I don’t only want to write games about black people. I also like bicycles. I knit. I love Irish and English folk music and I’m really interested in writing games that incorporate these folk ballads.

–

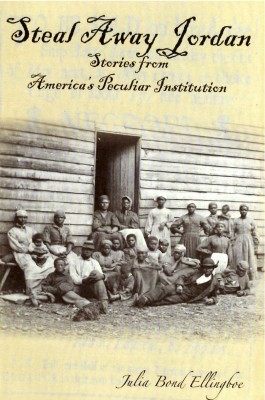

Featured Image is a public domain sketch of house slaves, featured in Steal Away Jordan.

–

Katherine Castiello Jones is a Ph.D. candidate in the Sociology department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she has also completed a graduate certificate in Advanced Feminist Studies. Her interest in role-playing started in college with a game of Call of Cthulhu. Moving from player to game master and designer, Jones has been active in organizing Games on Demand as well as JiffyCon. She has also written and co-authored several live-action scenarios including All Hail the Pirate Queen!, Revived: A Support Group for the Partially Deceased, Cady Stanton’s Candyland with Julia Ellingboe, and Uwe Boll’s X-Mas Special with Evan Torner. Jones is also interested in how sociology can aid the study of analog games. She’s written for RPG = Role Playing Girl and her piece “Gary Alan Fine Revisited: RPG Research in the 21st Century” was published in Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Role-Playing Games and the Media.