It’s inevitable. In Dungeons & Dragons or Pathfinder players will go to war over the rules. Can our wizard hit that orc party with a fireball spell? He was groggy from waking up and his aim might be off. In tabletop role playing games, which produce dozens of rulebooks, players have innumerable opportunities to get into the weeds when interpreting the rules. At the game table, all players treat one another equally, but this courtesy tends to privilege the loudest voices in the room as opposed to the smartest. I want to discuss one of these voices, the rules lawyer. A rules lawyer is a player who argues and interprets the rules of the game during play. There are two dominant characterizations of this archetype. On the one hand, we see a vociferous commentator who acts as a slog on the game. On the other, a crusader challenging breezy rules interpretations with canon, providing stability and more enjoyment. The common thread between these archetypes is that being a rules lawyer provides players with symbolic and linguistic capital. Furthermore, the proclivity of the rules lawyer toward masculine forms of discourse (such as argument) exemplifies the ubiquity of hegemonic masculinity in tabletop role-playing.

“Rules lawyering” is one of those terms that has been around for about as long as there have been people playing tabletop role playing games. The rules lawyer has commonly been seen as the invested intellectual, the Brainy Smurf of the role playing game who means well but comes off sounding haughty, preachy, and arrogant. In my group, we liken rules lawyering to the curse of lycanthropy – the worst thing in the world is for someone to become so invested in the game’s rules that they are “turned” into another rules lawyer. To be a rules lawyer, or to be referred to as one, is a pejorative in the roleplaying world.

Given the stigma that comes along with rules lawyering, why do people still engage in the behavior? What prompts players to feel like it is necessary to engage in rules lawyering behavior? Rules lawyering is a case study in hegemonic masculinity for game studies scholars. I posit that rules lawyering (like other terms in the feminist lexicon like mansplaining and cultural appropriation) has grown beyond its original meaning into something that is interpreted differently by the individuals who use it. My sense is, like these terms, rules lawyering is governed by the famous line from Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart in his analysis of obscenity: “I know it when I see it.” This implies that you don’t need a hard and fast definition for a rules lawyer; players know the behavior when it’s presented to them. Examples of interpretations of the rules lawyer are varied. Gary Fine defines the term as “a participant in a rules-based environment who attempts to use the letter of the law without reference to the spirit, usually in order to gain an advantage within that environment“. Slavicsek and Baker say in Dungeon Master for Dummies it is “a player who argues against a DM’s verdict or adjudication by making references to the rules”. I define the rules lawyer as a player who explicitly and fervently offers a different interpretation of the rules than the Game Master during gameplay. This definition acknowledges how conflict with the Game Master, impact on the overall group, and the agency of the rules lawyer all become important as social currency.

Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu believed that practices (like rules lawyering) can be analyzed as a system that explains the shared relationship between the individual (or actor) and the social world. By looking at the component actions of an individual, especially those habitual actions that allow the actor to conform to the system (habitus), one can get a better sense of what is valued by the actor and the system (capital), and physical and conceptual realms where valued knowledges, artifacts, and procedures are engaged (field). In terms of capital, while Bourdieu originally came up with three types (social, cultural, and economic), he later expanded with concepts of various other types, such as symbolic capital and linguistic capital. Symbolic capital involves the interplay between having a specific item of value and being able to appreciate it and convey its value. Linguistic capital concerns itself with the power of one’s discursive ability: the knowledge of languages and the “correct way” to speak them (such as dialect) and how that could transmit knowledge about one’s status.

Using practice theory as a model, there’s value in seeing the symbolic and linguistic capital of rules lawyering. Symbolic capital explains why such behavior is tolerated, but why the term can defy definition. To practice rules lawyering represents the ultimate expression of symbolic capital. A player understands the rules so deeply, so without error, that they are willing to argue with anyone (including the Game Master) about a meaning. Given that many rules lawyers engage in their initial challenge from a perspective of memory (meaning they aren’t reading a rule book when they levy their challenge), this reinforces the position of their symbolic capital by establishing these people as subject matter experts.

Rules lawyers must be able to not only understand the game mechanics enough to correct someone, but use the in-game language well enough to demonstrate mastery. Therefore linguistic capital is important in order for one to be an effective rules lawyer. If a player does not use the correct name for a spell, they come across as uninformed. After all, there is a difference between the spells Teleport and Greater Teleport; they cannot be used interchangeably! Therefore, it is important for the rules lawyer to not only know what they are talking about, but also to convincingly sound like they know what they are talking about. This balance of symbolic and linguistic capital is vital to be an effective (and successful) rules lawyer.

A great deal of the language that we talk about that characterizes rules lawyering has been discussed by sociolinguists who study gender. Linguistic patterns are gendered. Corrective and dominating discussion, for example, are linguistic features that the study of language tends to attribute to men. The interruptive nature of rules lawyering lends itself better to what sociolinguist Scott Kiesling refers to as “masculine discourse.” Linguists Deborah James and Sandra Clark demonstrate how culture perceives men to interrupt more than women when in fact there is no difference among genders in the behavior. Evidence suggests this “man talk” – a term popularized by linguist and gender studies scholar Jennifer Coates – isn’t inherent or biological, but a method of speaking that is cultivated in men through socialization. Citing works of past gender theorists, Peter Knussman notes that language is used to assert dominance among men, and interruptions are the key linguistic feature to convey this. He writes, “[Interruption use] is generally explained by the relative power of the participants which derives from their social status. The higher incidence of interruptions, thus, is seen in the relatively high social and economic status of men”.

The performance of rules lawyering can reinforce hegemonic masculinity in other ways. Kiesling theorizes that men’s friendships are heavily based on indirectness in conversation, and that interaction types like rules lawyering, while combative and at times overbearing, lead to a level of respect and can increase homosociality and affection between men. The performance is, however, disruptive and while it might lead two people closer, akin to tenets of hegemonic masculinity, it is destabilizing for the game – the social act suffers for the benefit of a small few. This connection between the arguing men, however, might be at the cost of others who share the table space. Indirectness is a common tactic of dominant groups, meaning those in other categories (racial ethnic minorities, sexual minorities, women, etc.) might interpret the interaction as arguing and find it disruptive, obnoxious, and diverting. Without experience in dealing with rules lawyering, the entire experience could seem off-putting to a table not used to the performance

While there are positive expressions of symbolic and linguistic capital, it could be argued that social capital is hampered. Unfettered rules lawyering potentially represents a drag on any game system. Few players not involved in the debate would want to engage in a lengthy discussion of whether the phrase “others touched” meant a person could be touching someone with their toe rather than their finger to get a spell effect! The discussion generally is between the rules lawyer, the GM, and the affected player, leaving others to either watch the production or wait out the experience. Given that tabletop role-playing games tend to be lengthy experiences in their own right, this adds to the duration but not to the experience for many players. As Walden points out, “participants are drawn to D&D because it is entertaining and enjoyable. The game is engrossing; participants identify with their character and suspend ‘reality’ in favour of fantasy.” Rules lawyering “suspends the suspension” in a way. Players are thrust back into a real world where their imagined characters again become words on paper governed by mechanics in a book. In the moment, it is understandable that no one likes a rules lawyer. Like Huizinga’s spoilsport, the rules lawyer can be seen as “shatter[ing] the play world itself. He robs play of illusion.”

Rules lawyering can have a much more direct effect on the social organism that is the gaming group. The nature of gaming, specifically role-playing games, emphasizes the shared experience and communal nature, and the power of imagination. Aubrey Adams states, “players fulfill social needs through group communication; because it was shown that players fulfilled needs related democracy, friendship, extraordinary experiences, and ethics, it can be extrapolated that meeting these needs serves as motivation for the game-play itself.” Rules lawyering, conversely, pushes the game structure and rules to the fore, calcifying the power of the social structure. In cultural capital Bourdieu notes three forms: institutional, embodied, and objectified. The rules lawyer, through his agency, proves his superior capital by displaying all three forms of cultural capital: institutional through superior specialized knowledge, embodied through a dominant, arguing demeanor, and objectified through the supply of books directly quoted to prove a point. The rules lawyer serves to police behavior, similar to the explicit gender policing Rapheala Best suggests occurs in elementary school. The rules lawyer is a vocal monitor, whose agency is guaranteed by authority granted him by cultural capital.

The explanatory nature of rules lawyering often takes an authoritarian tone, providing status to those who use it. Women and minorities, often outnumbered at the gaming table, might demur from rules lawyering behavior because of their internalized marginalization coupled with a sense of what capital they might lose if proven wrong. This only serves to reify the sense of expressive geekdom being White and male. For all the diversity we see around the table, the world of games is arguably a male preserve; the persistence of the rules lawyer only drives that fact. Thus, another way to view rules lawyering is as a means of reinforcing masculine power, thriving at the game table, a field of practice where one’s years of experience codes as a badge of honor. For many, the threat of the diverse table might not be consciously realized, but as the composition and configuration of groups grow, varied concerns of sexism, racism, cultural appropriation and the like may serve to sideline an assumption of tabletop games as a masculine refuge, or “man cave.” In these spaces, men representing the dominant group may feel they have no voice. Yet, as a rules lawyer myself, these conversations must take a back seat to game culture’s new, more inclusive, habit. “Sorry – that’s not covered by the rules.”

–

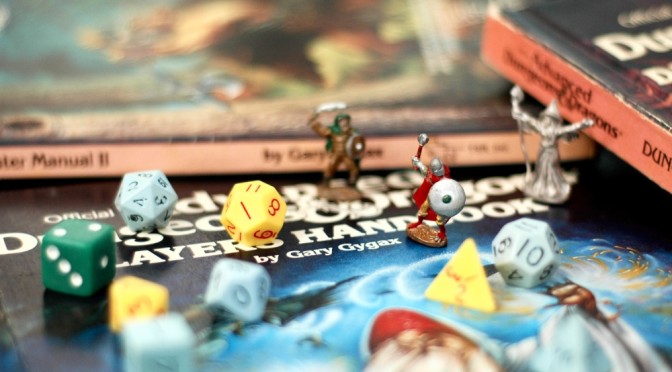

Featured image “Gary Gygax” by John Watson @Flickr CC BY-NC .

–

Steven Dashiell is a PhD candidate/ABD at the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC) in the Language, Literacy, and Culture department. His dissertation research investigates masculinity constructs and cultural identity of male students who were in the military. His research interests involve the sociology of masculinity, popular culture, narrative analysis, and linguistic anthropology. He has presented his work at several conferences, including the Popular Culture Association, the American Men’s Studies Association conference, Eastern Sociological Society meeting, and the American Sociological Association. In addition to his doctoral studies, Steven works for Johns Hopkins University as a Research Coordinator. Beyond the military, Steven has done research on Bronies, tabletop, computer, and card gamers. He can be reached at steven.dashiell@umbc.edu.