In the early fall of 2018, I embarked on a study that analyzed the gender and racial representation of game designers and illustrators in the Top 200 board games as ranked by BoardGameGeek (BGG), a table-top gaming community discussion board and online listing of 100,426 table-top games (as published on Aug. 14, 2018). My study also looked at the representation of gender and racial identities depicted on the cover art of the Top 100 BGG-ranked games. I found that the overwhelming majority of game designers and illustrators were white males, while white female or non-white designers and illustrators (defined as those of Asian, African, Hispanic and/or First Peoples descent) were under-represented compared to U.S. and Canadian population demography. My analysis uncovered that there was only slightly more diversity in the illustration and art design personnel responsible for creating the Top 200 BGG-ranked games. The cover art of the Top 100 BGG-ranked games was also found to over-represent white male imagery over that of female or non-white identities. Based on the analysis of a database of findings, this article discusses the debate around the lack of representation and diversity in the board game hobby.

Now, like any good film noir, since you know the ending, let’s start with how this study began. On May 2016, Asmadi Games launched the small box, card-based dungeon crawl One Deck Dungeon on Kickstarter.1 The game would go on to raise $122,632 U.S. dollars, punching past its initial modest $20,000 goal.2This solo or two player co-operative game was a pocket-sized dungeon crawler with a twist. The twist? All of the playable characters, and the box art were based on strong, diverse, female images. Designed by Chris Cieslik, with artwork by Alanna Cervenak and Will Pitzer, the game’s launch was yet another flashpoint in an ongoing board game community discussion around diversity and inclusion. A small collection of 1-star Amazon.com reviews cropped up around the game’s release. One reviewer called the game “One sex dungeon” and another called it simply, “sexist.”3 Reviewer Zach C on Amazon.com complained, “…only women characters. I guess they don’t want me… Misandry noted. If they make a version for me, or for both sexes, I may buy that.”4 Still other reviews were positive. redditor Hreha wrote, ‘Please forgive my gushing, but I love this game”; another redditor posted Nekokeki, “I absolutely love it too… so does my girlfriend! One of the few games I’ve been able to get her to play consistently”5 redditor LateToTheTable wrote: “The ONLY “issue” I’ve seen people complain about that game is that it has an all female cast. If that’s the worse thing I’ve heard people say about a game, then it must be pretty solid and you can continue to ignore those idiots.”6 Despite the game’s defenders, the apparent negativity of many reviews was notable.

The BGG discussion forums offer some insight into how the board game community regards the politics of representation. BGG is home to an active and mostly unmoderated network of threads under a category called, “Everything Else » Religion, Sex, and Politics.” According to a search of the forum, discussions of “whiteness”, racial and sexual representation and harassment appear in recent 2018 forum threads about topics such as “Sexual Harassment at Origins”, “The White Power Symbol”, “Confederate flags in the North”, “Treatment of conservatives” and “If You Could Change One Thing About The Hobby: What Would It Be?” In the latter thread about improving the hobby, one BGG forum poster replied, “Be more inclusive. I’d like to see more diverse designers, developers and artists of games and personalities such as reviewers and bloggers”; another poster wrote, “Better representation of women. Better representation of people who are not white people. Better representation of people who do not follow the social norms that straight Puritans have decided is the standard….”7A post responding to the criticisms that the hobby is sexist in a June 2018 forum entitled “Gencon” targeted pop culture critic, independent games scholar, and Gencon speaker, Anita Sarkeesian: “Sarkeesian is a hypocrit (sic) and a liar. She is completely blind to any other opinions then (sic) her own, and everything aside from her own is wrong, racist, sexist etc. As opposed to many of the people who has (sic) criticised her over the years, who have openly admitted to agreeing with her on occasion. Whatever she is gonna puke out on GenCon I can only imagine but It (sic) will most likely alienate 90% of the community from the discussion, so the remaining 10% can come together and feel good about themselves”8 It is clear that matters of representation, diversity and inclusion simmer, and occasionally boil, within the forums and across the hobby.

I am an avid, long-time gamer who identifies as a woman. I am also a member of various online board game forums such as r/boardgameson reddit, The Dice Tower Facebook page and of course, Twitter. There too, I have observed ongoing, highly combustive debates around board games, representation and inclusion. Without hard evidence, these debates can trend toward the speculative, and so I draw on the tools used by the film and television industries to perform an analysis of representation in the board game community.

The “Inclusion & Invisibility: Comprehensive Annenberg Report on Diversity in Entertainment” (CARD) was an ideal starting point for looking at inclusivity in board games.9 CARD illuminates the way for representation analysis. CARD acts as an exemplar for what close study and analysis can do to identify the issues around representation and ultimately, effect industry change. The study looked at those in front of the camera and behind the camera during a snapshot in time from September 2014 to August 2015. The leadership of the production companies and the speaking characters on TV, film and web series were painstakingly logged and analyzed (these CARD findings are discussed in more depth later). The CARD study laid bare imbalance and inequity, revealing once again that film, television and web series have a diversity problem. Studies conducted in the PC and console gaming world generated similar snapshots of an unbalanced media landscape and an absence of representation.10

Taking a page from CARD, I decided to look at the people behind the game box, the designers and illustrators, and the representation on the box itself. The goal was to uncover an accurate snapshot of representation, provide a picture of systematic patterns and even, help the industry improve. I embarked on this painstaking process knowing full well the limitations of quantitative analysis. This study would be strictly focused on “just the facts, ma’am” (apologies to Stan Freberg’s parody of Dragnet’s Joe Friday), to deal in the point salad of raw counts of representation11

This research study was designed to answer the question: To what extent are female and non-white designers and artists present in the production of the Top 200 BGG-ranked games? My second question looked diversity of representation: How frequently do the images of women and non-white identities appear on the cover art of the Top 100 BGG List? To answer these questions, I conducted a quantitative content analysis of the board game credits in the BGG listings of the Top 200 BGG-ranked games, and Top 100 BGG-ranked listings respectively as published on Aug. 14, 2018. The CARD study and the seminal Williams, Martins, Consalvo and Ivory study of gender and racial representation in video games provided foundational and theoretical frameworks for the analysis of the quantitative results gathered during this study. Using cultivation theory and the vitality framework, I will discuss the impacts of under-representation of certain demographic communities in the production and game imagery on the board game hobby as a whole.12

Background

Board games sales topped $1.5 billion (U.S) in the U.S. and Canada for the first time in 2017.13 Fueled in part by the growth in the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, North American sales represent a third of the total aggregate global games and puzzles sales at US$3.2 billion, with growing interest in games spanning multiple generations of consumers, young and old.14 The compound annual growth rate of board games is expected to approach 23 percent, with analysts suggesting that it might taper off after 2022.15 Board games have cracked the billion-dollar mark, and with this success, the number of available titles is increasing. There are 16,817 table-top game projects on the Kickstarter platform alone.16 As such, the board game hobby has been experiencing a renaissance in both sales and new titles. Scholars have suggested that board game enthusiasts enjoy the face-to-face interactions afforded them by table-top play. “Hobby board game participants may experience the joy of socialization, the game being little more than an alibi for people to get together to enjoy each other’s company.”17Whatever the manifold socioeconomic reasons behind the growth in sales and the broadening social interest in analog gaming, there is little question this hobby is an important cultural practice, on par with film, television and video games, and eminently worthy of close critical study, analyses and commentary. Using CARD as a model, this study is designed to subject the board game industry to rigorous scrutiny. This analytic labor will help the hobby to evolve, and hopefully even flourish. With raw numbers, we can look to what representation means to the economy of board games on a whole, both in terms of games production labor and wider sales of games.

Pinning down the demographic composition of board game players is a very tricky enterprise. Demographic studies for digital game players abound, while recent surveys of board game players are often informal and conducted by games publishers, or enthusiasts online. A relatively recent demographic survey that elicited 3,427 responses among a publisher’s subscribers that found 91.7 percent of respondents were male and 8.1 percent were female.18 Another 2016 table-top gamer demographic survey of 2,397 respondents that found 24 percent of board gamers were women, 1.1 percent non binary and 0.6 percent were trans, while the remainder—74.3 percent—identify as male.19 The overwhelming majority of survey respondents were also white, with survey reporting that 2.1 percent were Chinese, 2.7 percent were Latin American, 0.6 percent were Aboriginal and 0.7 percent were Filipino.20Recent digital gamer studies tell us that video gaming is increasingly pervasive and mainstream in the U.S. with 64 percent of U.S. households containing a device used to play video games. Adult women players represent 33 percent of all U.S. gamers and in fact, outnumber males under 18 years of age.21

Film and television, and digital game scholars have engaged in robust analysis around representation. Overall, studies of gender and racial representation on television, film and increasingly, digital gaming have revealed systemic under-representation of female and non-white identities.22 In television shows, movies and web series analyzed from September 1, 2014 to August 31, 2015, research found that there were only one female to every two males on screen, and female characters comprised 28.7 percent of all speaking roles in films.23 The CARD study revealed that 71.7 percent of on screen characters in films, television series were white, 12.2 percent were Black, and 5.8 and 5.1 percent were Hispanic and Asian respectively. In 150 video games analyzed in a large-scale content analysis, male characters were found to represent 85.23 percent of all video game characters with only 14.77 percent of characters representing female identities; these researchers also found that 41 percent of the games surveyed did not include any female characters at all.24In another analysis of 200 randomly-chosen casual games, only six percent or eight games out of a sample of 130 games with human characters had non-white primary characters, and an analysis of 54 of the most-downloaded digital casual games, 92 percent of the human characters were found to be white.25

Whither representation? What impact does a lack of representation in media have on culture and identity? According to cultivation theory, absent or negative representation in media can impact the perceptions of social realities in day-to-day life.26 Other theorists suggest that the invisibility of demographic groups can lead to those communities experiencing feelings of disempowerment and irrelevance.27 Cultivation theory posits that, over time, exposure to media that selectively limits or presents stereotypical depictions of certain demographic segments can shift social perception and drive real-world decision making. It is argued that television in its mass market reach and enjoys high rates of consumption, it is a primary persuasive and socializing force in society.28 When we consume film and television programming, or in this case, engage in gameplay, our perspectives on our reality is shaped. Critics of cultivation theory suggest that there can be a level of imprecision and missing nuance in the way in which cultivation theory is utilized in the categorization of the messages purportedly being cultivated, or that the audience doesn’t always receive the messages exactly in the way they were intended by the authors of those same messages.29This study offers a counterpoint to cultivation theory detractors, those who argue against any systemic patterns in media messaging. This study provides quantitative data to demonstrate a pervasive pattern through this selected sample.

Cultivation theory can be used to explain pervasive toxicity in gaming life online. Research has identified that online gaming tends to be a masculine space with limited female representation.30 Girls reported playing ostensibly male-dominated games only when they were able to play with another male friend/ally.31 A study of multiplayer online games found that harassment of female players, who are often a minority in many game platforms, resulted in online female gamers adopting an assortment of coping strategies.32 These coping strategies included gender masking, or disguising their gender identities, denial of the issue or telling themselves that harassment wasn’t an issue, blaming themselves and ultimately, complete avoidance of the game environments themselves, or simply quitting the game or leaving the multiplayer platform entirely.33

Research into representation in contemporary board gaming is still nascent and emerging. My contribution here expands and builds upon work conducted in the table-top community itself.34 One study found that only five percent of games analyzed featured only women on the cover, 5.8 percent featured a group of people made up of primarily women and 62.6% had a cover that featured only men.35 The same study identified slight improvements in covers featuring women or primarily women on the cover art from 2009 to 2015 and slight decreases in men or primarily men on the covers, a large gulf between male and female representation, in favor of male imagery, was still observed.36

In an analysis of representation and inclusion of women in hobby gaming, Gil Hova noted that “…while not overtly hostile to women, still has a bunch of invisible ropes that keep many women from enjoying the hobby.”37 The lack of representation on cover art has been identified as one of the barriers blocking women from feeling included or wanting to participate in the hobby. Another study uncovered similar findings.38Interviews with woman gamers found that interviewees desired more diversity and inclusion in board gaming, wishing that the community would include more opportunities for women, racial minorities and families to participate. Those interviewed also pointed to a lack of representation of women in board game artwork and playable characters as a barrier to more women feeling included in and engaging with the hobby.39

A Geek & Sundry commentator notes: “(w)omen, people of color, and other groups still find some friction feeling accepted in the gaming community.”40 The Dice Tower board game review channel contributor Suzanne Sheldon spoke with fellow contributor Mandi Hutchinson about experiences as a woman of color in board gaming. Sheldon noted games such as The Dead of Winter (2014) by Plaid Hat Games and Capital Lux (2016) by Aporta Games, incorporate diversity in the games’ production teams, cover art and playable characters, and have made critical strides to reflect real-world diversity. In a reflection on diversity and inclusion, Sheldon noted:

“Whether you think it is pandering or a step in the right direction, when I look at a game, and I think ‘oh, my gosh, I’ve been acknowledged’, it is very powerful for me. I really value publishers and designers who are doing that.”41

Drawing from contemporary media representation studies conducted in film, television, and video games, I crafted the following research questions: To what extent are female and non-white designers and artists present in the production of the Top 200 BGG-ranked games? How frequently do the images of women and non-white identities appear on the cover art of the Top 100 BGG list? A content analysis on the Top 200 BGG-rated games for designers and illustrators and a visual content analysis of the cover art of the Top 100 BGG-ranked games was undertaken to answer the research questions.

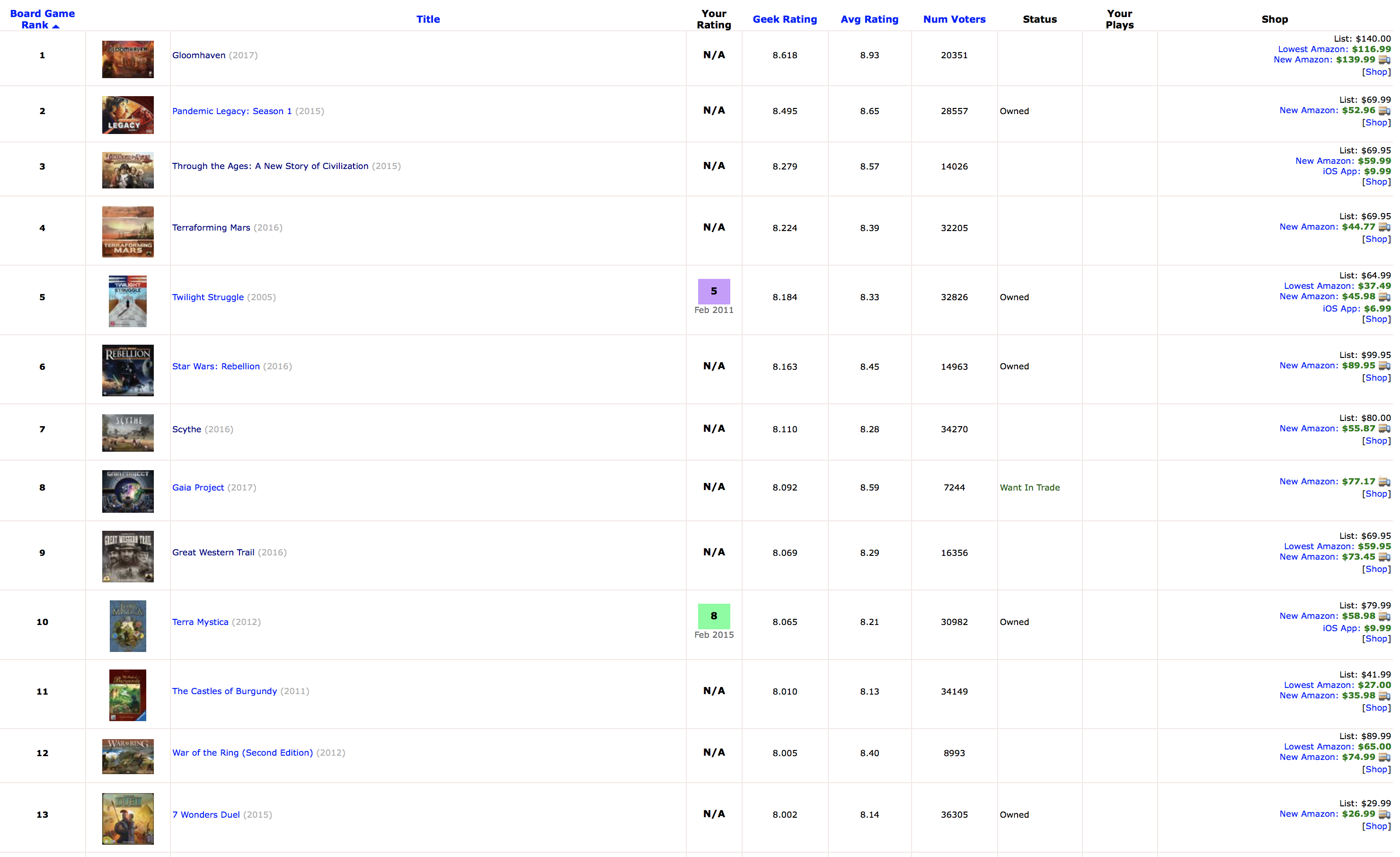

Based on the popularity of the BoardGameGeek, I made a decision to select my sample with a focus on designers and illustrators from the BGG-ranked Top 200 list. BGG is one of the premier board game ranking sites with 1,493,012 registered users as of Feb. 4, 2017 and reporting a 25 percent growth in unique visitors from 2016 to 2017 to 5 million unique page views.42 The Top 200 list represents the ratings of 1.9 million registered users, as such the BGG community is actively used and has a well-established community. Founded in January 2000 by Scott Alden and Derk Solko, games on BGG are ranked by registered users the community through user ratings.43 Based upon this data, a sample from Top 200 and Top 100 would allow me to select popular games that are being actively played by board gamers, thus linking the resultant findings to current cultural practice in the hobby.

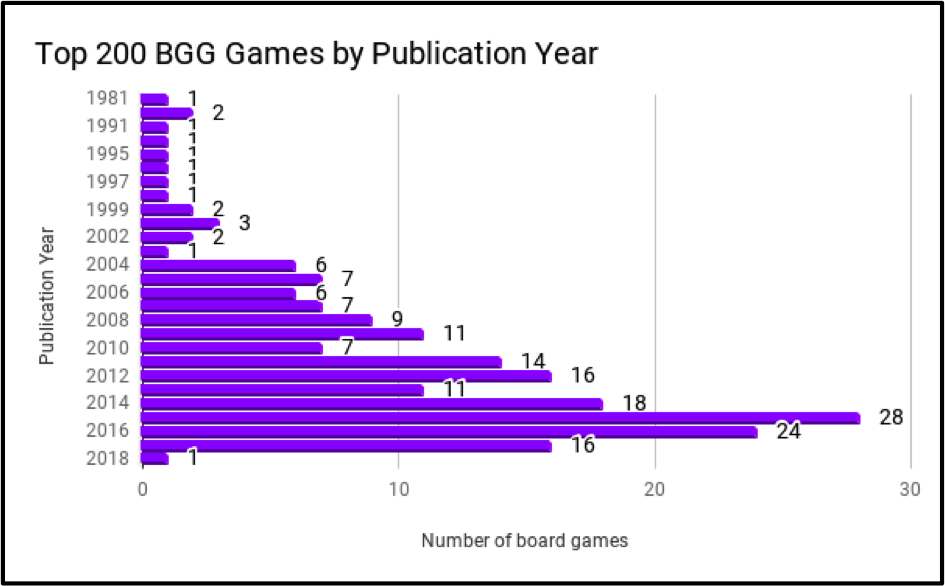

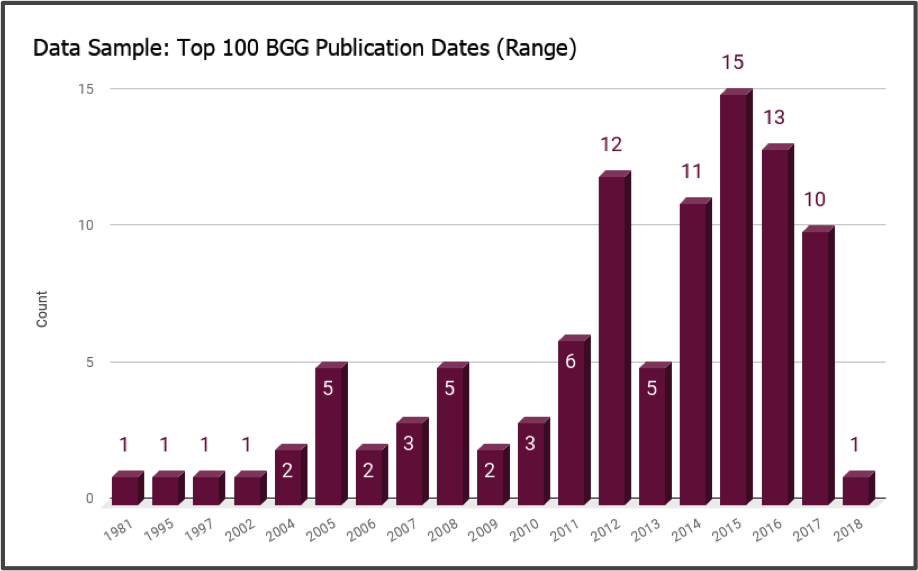

Looking at the Top BGG-Ranked 200 by publication year, I found that the oldest games in the analyzed sample were the classic abstract strategy games Go dated at 2200 (Before Common Era) BCE on the site (but estimated to have been created around 2357-2255 BC) and Crokinole dated at 1876.44 Excluding those games from the Top 200, the average publication date of the games are 2012, with the earliest being 1981 and the latest, 2018. The majority of the list are games from the last decade, 2008 or older, at 155 games. Games from the last five years represent nearly half of the analyzed list at 98 games representing 2013 or later (See Figure 1).

An anticipated objection arises at this point: Given the continued popularity of older games, does this list still reflect the hobby community’s values? To answer this, I looked at the Top 100 BGG-ranked games. The majority of the games in the Top 100 BGG-ranked list, at 56 games, were published between 2013 and 2018 or within the last five years of this article’s publication (See Figure 2). Board game enthusiasts are often accused of being a ‘cult of the new’ and the fact that the top positions of the BGG rankings are occupied by relatively recent additions would seem to lend some credence to this claim.

Data Collection

I coded the Top 200 BGG designers and illustrators against the following four categories: white male, white female, non-white female and non-white male. Total counts for each of the four categories were tallied in a spreadsheet. The process for coding included field notes, frequent rechecks and double checks of data counts. All of the coding was conducted from August first to September fifteenth,2018. The information on designer and illustrators of each board game started with the BGG profiles of the identified individuals. When I could find no BGG profile or BGG-recommended external links, I sought out designer and illustrator social media profiles (Instagram, LinkedIn, Facebook, etc.) and, wherever possible, looked at online portfolios and/or corporate profiles. In many cases, this process also involved reading interviews with the designers and illustrators to find additional information. This process was highly time-consuming, taking over ten hours each week, in the course of my five week data collection phase. There were two cases in which data on the illustrators was not possible to accurately catalogue. Magic: The Gathering (1993) has had more than 500 artists since its release, and Legendary Encounters: An Alien Deck Building Game (2014) has listed an unnamed production staff as contributing to the production of the cover art work and more than 600 cards contained within the game. As such, these two games were excluded from this study.

A key consideration during the coding process for both designers and illustrators, as well as for the cover art, was carefully defining whiteness. I used the definition of “white” as used by the U.S. Census Bureau as those “having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.”45 “Non-white”as a coding construct was defined as anyone of South Asian, Chinese, Black, Filipino, Latin American, Southeast Asian, West Asian, Korean and Japanese, linking to the Census categories for both U.S. and Canada’s definition of visible minority.46 I recognize that the concept of whiteness and non-whiteness are themselves problematic categories in that they assume an authentic origin to a group, which is itself culturally and politically fluid.47

In the Top 100 BGG cover art coding process, I opted to catalogue the representation of all of the visible surfaces of the Top 100 game’s cover art. The decision to limit to the Top 100 BGG-ranked games was done for reasons of time, and access to the games themselves to facilitate the process of accurate data collection. The cataloguing process included the front, back, top, bottom and sides of all of the Top 100 BGG-ranked games. The logic behind this decision was that someone evaluating a game in a board game store or online might view the full cover art in making a purchase or play decision. In this process, I looked for any representative images including images of the game board, simulated game setups on the back of the box, miniatures (tokens/pawns/pieces/standees), photographs of the designers and card faces. The only exceptions to this rule were the publisher logos and legends for number of players; these elements were excluded. The coding included the painstaking process of counting tiny images in large crowds of soldiers, horses, birds, figures in the distance, even shadowy humanoid figures. This detail was captured in six coding categories: white male, white female, non-white female, non-white male, gender indeterminant, and animals or aliens, which was defined as otherworldly, extraterrestrial beings. Total counts for each of the six categories were tallied in a spreadsheet. Based on new discoveries made throughout the process, coding required many rechecks and updates throughout the data collection process. I decided to do a total count of all figures rather than assessing the relative prominence of images which might be viewed as a subjective exercise. A raw total count would allow me to uncover the representation on a relative scale, whether certain gender or racial identities were prominent or not. I did, however, take field notes on my impressions and relevance prominence of female and non-white identities on the cover art.

Findings

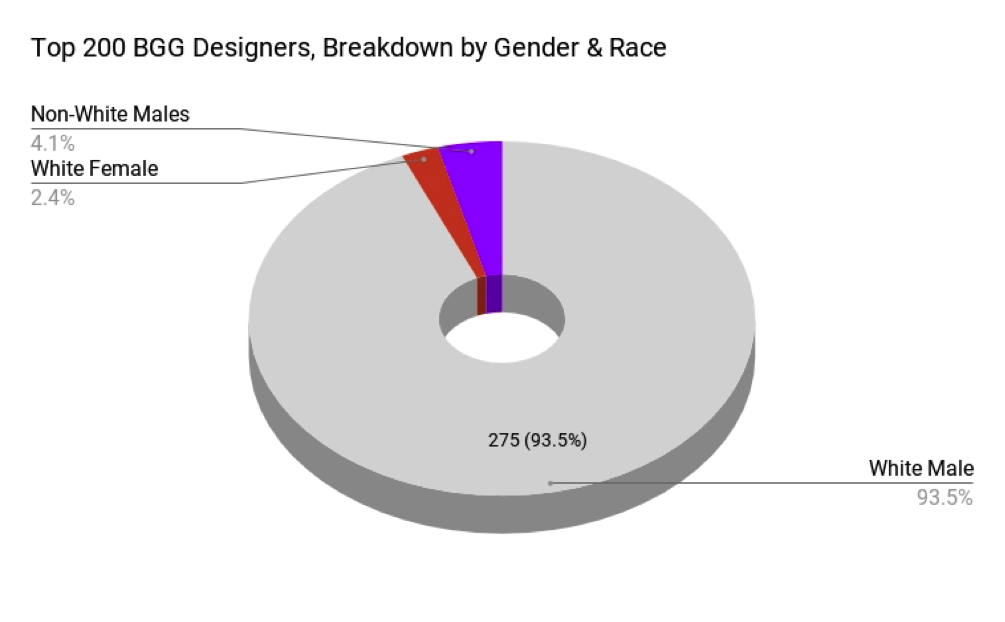

White male designers were over-represented compared to the population demographics of the U.S. and Canada in the design of the Top 200 BGG-ranked games with 275 white male designers, representing 93.5 percent of the total. White women and non-white men represented only 2.4 percent and 4.1 percent respectively, and there were no women of color designers in this sample (See Figure 3). Only 7 games within the Top 200 BGG games had a white female designer solely or jointly responsible for the game design. Game designer Nikki Valens was the sole non-male designer for the 22nd-ranked game, Mansions of Madness: Second Edition (2016). Valens was a co-designer for the number 47th-ranked game, Eldritch Horror (2013) .Peggy Chassenet was co-designer for the legacy game T.I.M.E Stories (2015), Suzanne Goldberg was a co-designer for the Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective: The Thames Murders & Other Cases (1981), number 65 on the BGG top 200. The 179-ranked Exit: The Game — The Abandoned Cabin (2016) and the 113-ranked Village (2011) were both jointly designed by Inka Brand. Flaminia Brasini was jointly responsible for the design of the 142-ranked Lorenzo il Magnifico (2016).

Only 12 games in the Top 200 BGG list were solely or jointly designed by a man of color. Prolific Canadian designer Eric M. Lang was solely responsible for the 23th-ranked Blood Rage (2015), 52nd-ranked Rising Sun (2018), and a co-designer for the 88th-ranked Arcadia Quest (2014) and 93rd-ranked Chaos in the Old World (2009). U.S designer Isaac Vega was a co-designer for 66th-ranked Dead of Winter: A Crossroads Game (2014), Prashant Saraswat is a co-designer for 25th-ranked Mechs vs. Minions (2016), Jonathan Ying co-designed 28th-ranked Star Wars: Imperial Assault (2014), Wei-Hwa Huang co-designed 60th-ranked Roll for the Galaxy (2014), Ananda Gupta was a co-designer 5th-ranked Twilight Struggle (2005) and Jesús Torres Castro was a co-designer of the 81th-ranked Pandemic: Iberia (2016). Hisashi Hayashi solely designed 98th-ranked Yokohama (2016) and Shimpei Sato solely designed 180th-ranked Onitama (2014).

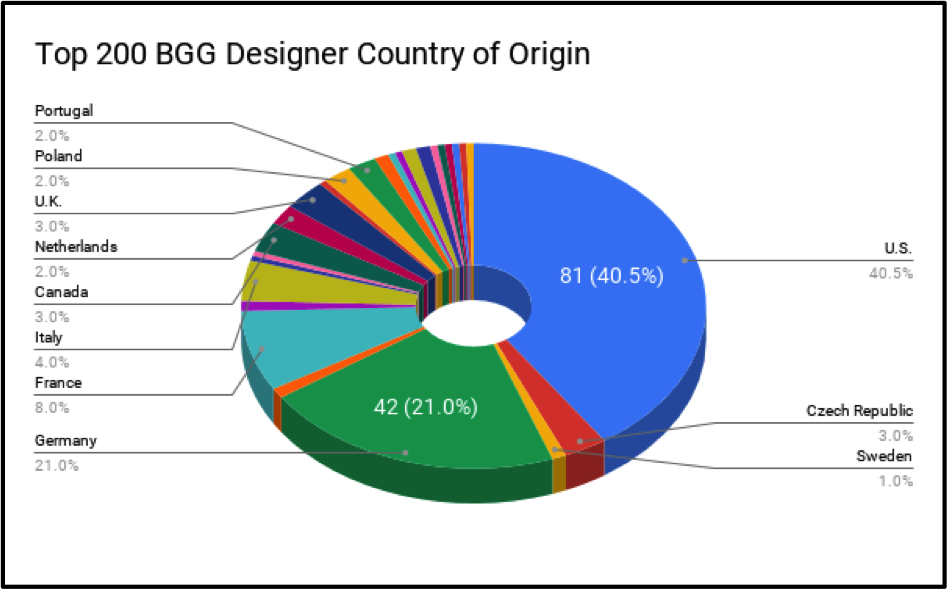

While board games are played around the world, this sample of the Top 200 BGG-ranked games were designed by predominantly European and North American creators. U.S. designers were represented at 40.5 percent, followed by designers from Germany at 21 percent, France at eight percent, Italy at four percent, and Canadian, Czech Republic and UK designers at three percent, Netherlands, Poland and Portugal each respectively represented two percent, Switzerland, Belgium and Japan at one percent. Ukraine, China and Slovakia each represented a half of a percentage point respectively (See Figure 4). To gather this data, I pinpointed where each designer was born based on biographical information online. In the case of Crokinole and Go, where the designer information was not listed on the BGG forum, box copy or third-party game website, or otherwise subject to debate, I traced these games origins to historical accounts. Both were said to have been created in Canada and China respectively.48

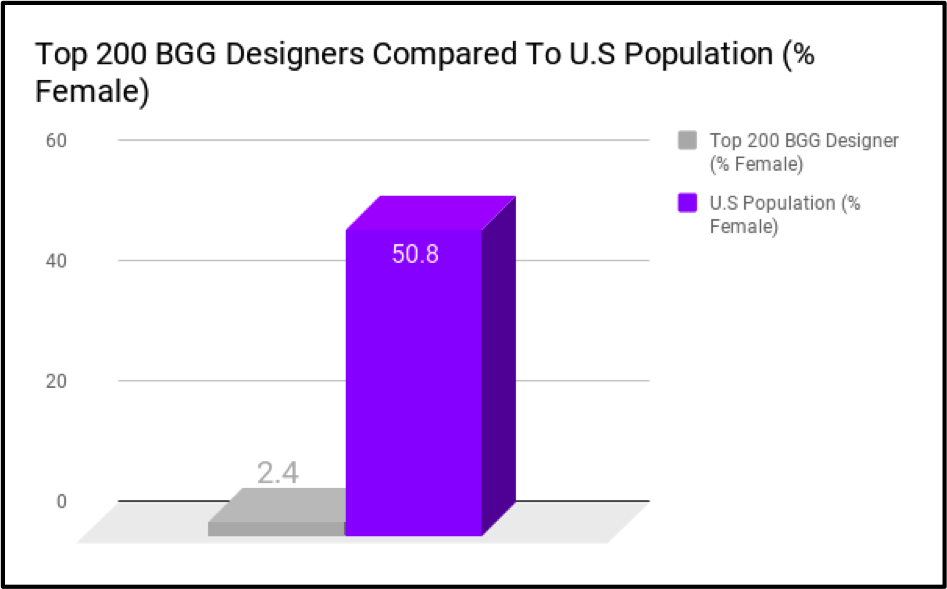

Looking at the Top 200 BGG’s representation compared to population, I discovered women and non-white designers are under-represented in the sample when compared to North American population demographics. Females made up 50.4 percent and 50.8 percent of the total population of Canada and U.S. respectively. Figure 5 demonstrates the under-representation in designers when compared to current U.S. demography. Similarly, persons of color are under-represented in the findings for designers. One out of every 5 people in Canada is a visible minority, non-white or person of color; U.S.residents identified as white at 72.4 percent and 27.6 as a person of color.

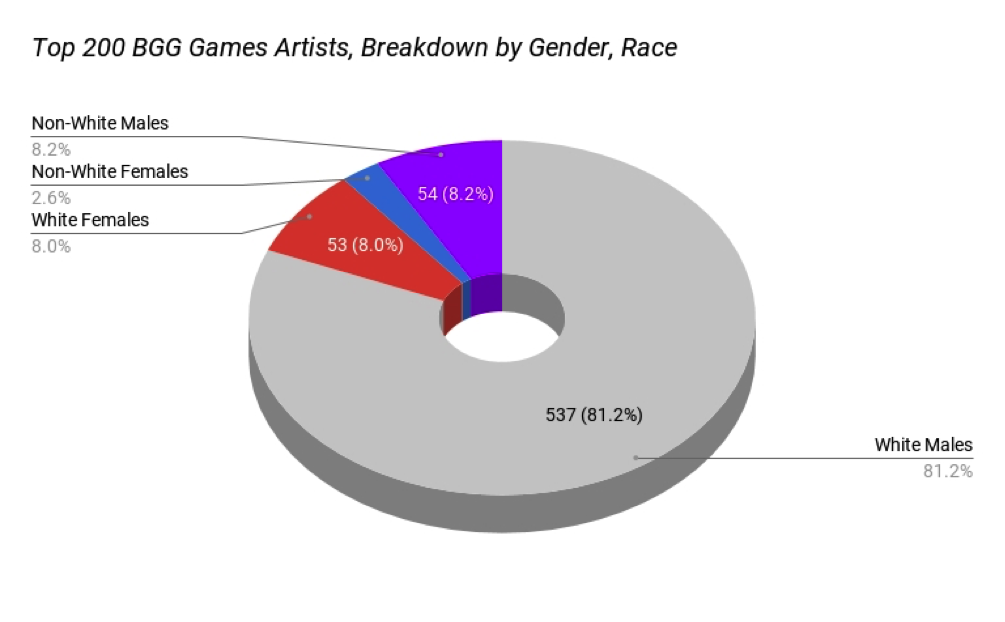

There was only slightly more diversity in the illustration and art design personnel responsible for creating the Top 200 BGG-ranked games. White males represented 81.2 percent or 537 in total, white females numbered 53 or eight percent, there were 54 men of color or 8.2 percent of the total and 17 non-white women or 2.6 percent (See Figure 6). This finding is interesting as it represents a small but measurably larger amount of representation and diversity in the ranks of illustrators. While one side of the production divide, the designers, are predominantly men, this side, representing the creative artistic component of game production, has better–albeit (still very small) percentages of diversity.

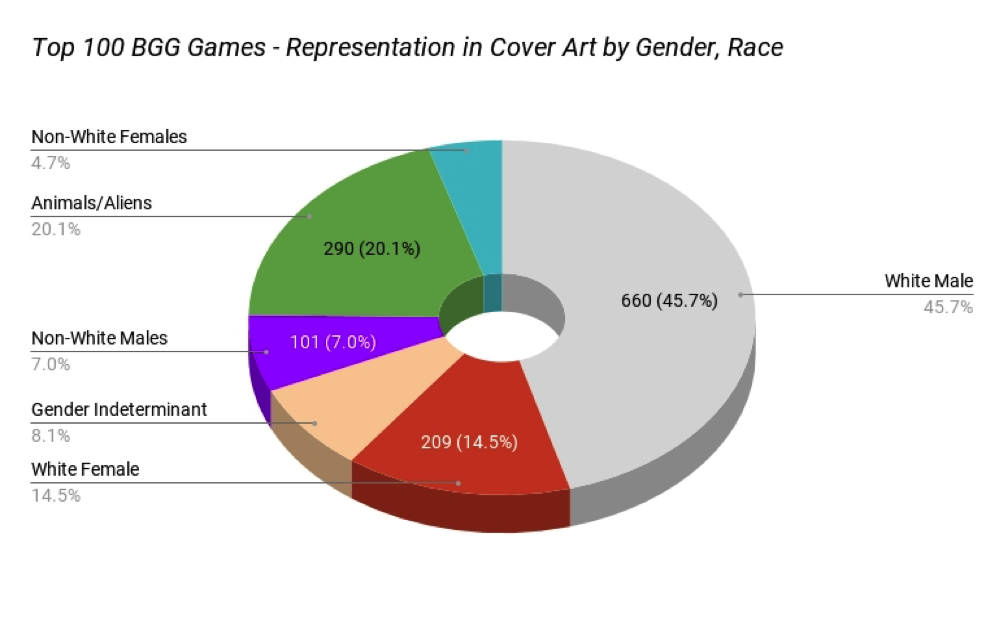

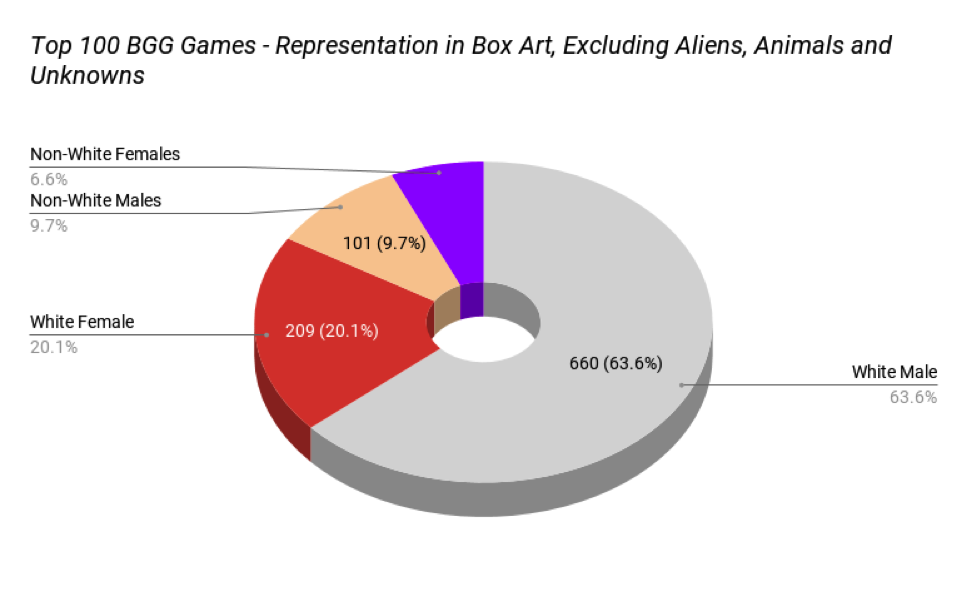

Overall, there were 869 white characters depicted on the cover art compared to 169 representations of non-white or people of color in the Top 100 -ranked games. White characters formed the significant majority at 83.7 percent, while representations of persons of color were 16.3 percent. Males were represented 761 times or 73.3 percent versus 26.7 percent or 277 times. A little more than eight in 10 representations were of white persons, and slightly more than seven in 10 representations were male. Only nine games of the 200 games featured no representation of any kind, neither humans, nor alien or animals, and were completely abstract in design. Star Realms (2014), for example, featured only space ships. Other abstract games included classic games such Go and Crokinole, and more recent games Azul (2017) and Patchwork (2014). Excluding these abstract games, white males made up 45.7 percent or 660 figures across all 100 games. Animals and aliens formed the second-highest percentage at 20.1 percent or 290 representations. White females comprised 14.5 percent of the representation on the Top 100 BGG-ranked games or 209 figures, women of color were at 4.7 percent. Representations that reflected a non gender binary or gender fluidity could not be ascertained in this analysis. Genders could not be assessed in 8.1 percent of the cases, this was often due to capturing figures in silhouette, shadow or blurry figures in the far distance of an image. Men of color were only represented at seven percent of the total, or 101 representations (See Figure 7).

Excluding aliens and animals and instances where gender couldn’t be determined, white males were portrayed in game cover art at 63.6 percent of the time, white females were represented at 20.1 percent, men of color and women of color were represented on covers 9.7 percent and 6.6 percent respectively (See Figure 8). Agricola (2007), Star Wars: Imperial Assault (2014), Android: Netrunner (2012), Pandemic (2008), Ticket to Ride: Europe (2005), The Resistance: Avalon (2012)all feature prominent women on the front cover. Queen Elizabeth I makes a prominent appearance on both Through the Ages: A Story of Civilization (2006) and Nations (2013).

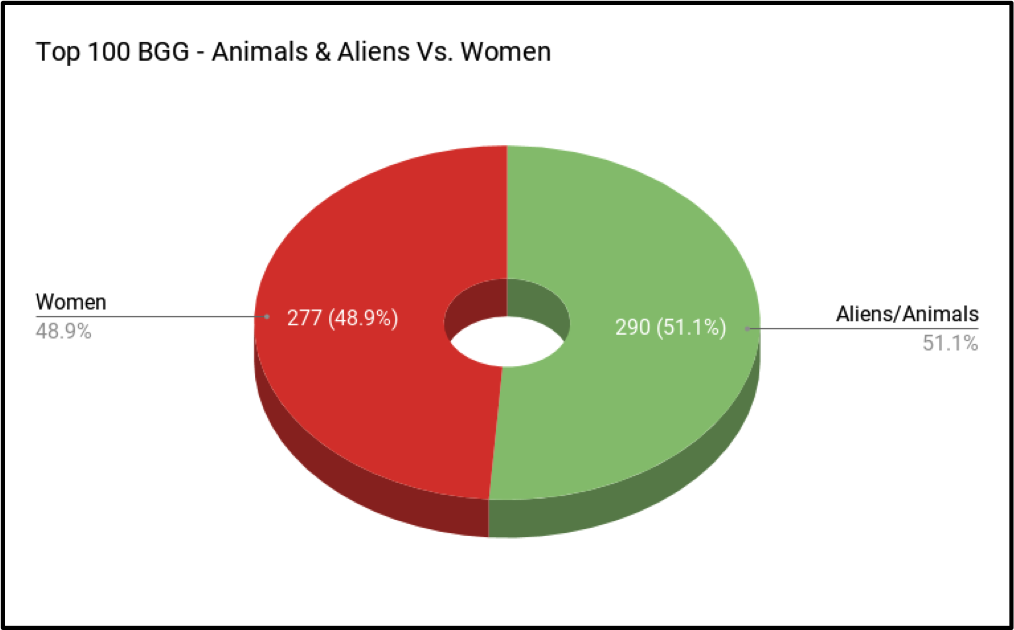

There is a disheartening study which points out that consumers are more likely to find a sheep on the cover of a board game than a woman. Erin Ryan’s analysis of Top 20 BGG-ranked games from 2009-2016, found there were more games with sheep on the cover than women.49 This study verifies this finding. I determined that, today, as a consumer of the Top 100 BGG games, one would be slightly more likely to see an image of an alien or barnyard animal (horses, sheep, birds, dogs) than one would be likely to see board game cover art with a woman (See Figure 9). As noted earlier, my analysis was based on total counts rather than Ryan’s focus on prominence as a key metric of analysis. In my analysis, I observed that aliens or animals were featured 51.1 percent of the total representations on the Top 100 BGG-ranked games while women were featured on 48.9 percent of the overall total.

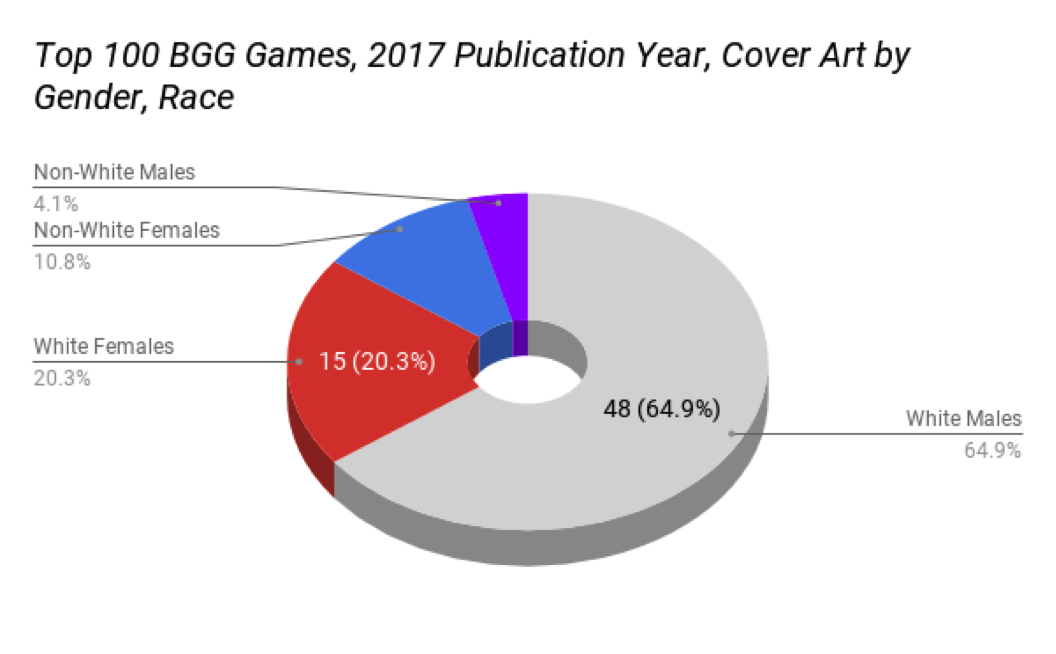

Based on this sample, diversity on production and design teams, and cover art representation appears not to have improved in recent years. There were no persons of color nor women designers for the ten games published in 2017’s top 100 BGG-ranked games analyzed for this study. The results got only marginally better for illustrators, with white males being included 76.7 percent of the time, white females representing 10 percent of the total, women of color and men of color both coming in at exactly 6.7 percent respectively (See Figure 10). As for cover art, the analyzed games published in 2017 were found to have 48 white males represented, there were 15 white females, 23 figures where gender could not be determined, eight non-white females and three non-white men depicted (See Figure 10). Overall, the numbers were similar to the total Top 100 BGG-ranked findings (See Figure 8).

Limitations and Further Work

This study is limited in the ways that many other quantitative studies are limited. Questions about how a lack of representation is received by players are beyond the scope of this work. A research effort around how players feel about representation in the hobby would require additional qualitative and quantitative analytic effort. This content analysis was moderate in scope, limited by time and resources. Admittedly, the decision to look at the Top 200 BGG-ranked games for the production and design teams, and the Top 100 BGG-ranked cover art, resulted a disjoint in the possible analysis. With more time and resources, I would like to look at a larger sample size for both the production staff on the games and diversity across a wider range of BGG-listed games’ cover art. Opportunities for future investigation include cataloguing in-game components and particularly playable characters for gender, racial and LGBTQ2A identities. As noted earlier, an analysis of the illustration teams for Magic: The Gathering (1993) and Legendary Encounters: An Alien Deck Building Game (2014) could be a study entirely on its own.

This study did not look at the larger matter of problematic, negative or stereotypical representation, either. The definition of whiteness is still another recognized limitation of the study. There might be some that might disagree with the U.S. Census definition of whiteness I employed for this study, feeling it either an entirely too restrictive or too expansive a frame. This limitation is an opportunity for further scholarship and discussion.

Discussion & Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate that both behind the box and front of the box representation in these top-ranked BGG games fall profoundly short of reflecting real-world population demography.

This study found a preponderance of white males occupying key roles in the design and illustrator roles of the Top 100 BGG-ranked games. There were 275 total white male designers, representing 93.5 percent of the total designers responsible for the design of the Top 200 BGG-ranked games. White women and men of color designers represented only 2.4 percent and 4.1 percent of the total respectively. The findings were only slightly more diverse for the illustration teams with white males representing 81.2 percent or 537 in total, white females numbered 53 or eight percent, there were 54 men of color or 8.2 percent of the total and 17 women of color or 2.6 percent. These numbers fall short of being representative of North American demography. Based on this sample, diversity and equity behind the box was found to be highly limited. Drawing inspiration from CARD, my goal with this study was to help move the conversation forward on the issue of representation and perhaps, spark changes in the industry and hobby.

The cover art of the Top 100 BGG was also found to over-represent white male imagery over that of female or non-white identities. More than eight of 10 images on cover art represented white characters at 83.7 percent. In the U.S., an estimated 27.6 percent of the population is non-white. Slightly more than seven in 10 cover art images were male at 73.3 percent, with female images representing 26.7 percent. More than 50 percent of the U.S. and Canadian population are female.

These findings bring us, inexorably, to wider questions. Why are so few women and non-white people involved in or represented on the covers of popular table-top games? Why should the analog gaming community care about representation? In the face of invisibility or limited representation of non-white and non-male talent, is the board game industry and community being stunted in its possibilities? Does the relative lack of representation on board game cover art telegraph a message to women and people of color that gaming is simply not for them? Cultivation theory and the vitality framework suggest that the answer is decidedly: Yes.50 Worlds in film, television and games become microworlds or reflections of our real-world power dynamics, demonstrating the centrality of an in-group, or marginalization of an out-group. Imagery that is viewed, or in the case of board games, played repeatedly, is more readily called to mind. Invisibility in media can have a cumulative, chilling and often, profoundly negative impact on marginalized groups.

Media, such as board games, shape our cognition. We make and design what we know, reflecting what we see. We don’t know what we don’t know. Perhaps, we are what we play. Our cognition is steeped in, formed and refined in the culture in which we live, work and play. Ergo, the fantasy game worlds we create, are limited fundamentally by our experiences and our narrow cognition. Per Shaw, we understand that those who argue against representation believe that game worlds should be unbounded by (so-called) hand-wringing about recognition and reality.51 Those on the other side of the debate suggest that if the overwhelming majority of imagery, of the faces we see in board game design, in production, at conventions, in board game stores are white males, the implicit message is that white males are the in-group, an in-group nurtured and supported by the explicit and implicit messages being shared within the hobby.

While it is understood that quantitative analysis has its limitations, the stark absence of diversity in this sample is laid bare. These numbers have a weight, a thud factor that doesn’t allow for much equivocation or grey places in which to hide. This study will give neither aid nor comfort to those who argue that there is ample representation in board gaming or the hobby has somehow, in recent years, succumbed to political correctness, and over-corrected in favor of traditionally marginalized groups. Still further, there are those in the hobby who might just throw up their hands in exasperation, reminding us that we are talking about games here. The message so often is: Just shut up and play. Find another hobby if you don’t like it. Duh, gaming is dominated by white men, because THEY play games. Why don’t you play abstract games if it bothers you so much?

As we look at these findings we see a gap, gulf, a void. Rather than a magic circle suggested by some theorists, we might see, instead, a vicious circle or a feedback loop of exclusion and confirmation of the in-group.52 Cultivation theory suggests that a marginalized out-group receives those implicit and explicit messages of exclusion loud and clear.53 Within the vitality framework, we might understand that the ingroup depicted in media is, in turn, powerful, has agency, even possesses unique, special and even super-heroic qualities.54 The ingroup is more present, and therefore, more important and powerful. The drip-drip-drip of unbalanced representation confirms a distorted understanding of reality and perpetuates itself. A community without representation begets new, fantasy worlds without representation. And round and round we go.

The board gaming community, like online digital gaming, based on the available data, appears on its surface and in many layers underneath as a white male-dominated space. Looking again to the 2018 study of female online multiplayers, women shared their strategies for coping with male-dominated spaces, including hiding their gender identities (an affordance not possible in face-to-face gaming), denying issues around exclusion or harassment, blaming themselves for issues or quitting the game or leaving the multiplayer platform entirely.55 As we consider the numbers in my study, one may wonder: do women and people of color stay away or quit board gaming because they are marginalized, unrepresented or invisible? Does a lack of representation contribute to a community where harassment and marginalization flourishes? Do the issues this study illuminate, stunt the growth of the community and the board game market? These are questions for future research, and questions that publishers and members of the community might well ask themselves. For some publishers, the need for diversity and representation in board gaming seems to be settled science. Amadi Games co-founder and the games founder Chris Cieslik and designer of One Deck Dungeon gave a reddit a r/boardgames interview commenting that reddit discussions on “diversity and inclusiveness are still ‘controversial’ which” which he found personally “kind of silly.”56 All in all, this study raises more questions than it answers. In a way, this work is akin to a scoring phase of one game round. It isn’t, by any stretch, the final score. All of the questions this study raises warrant future investigations, scholarship, analyses and discussion. The old business saw, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it” attributed to management guru, Peter Drucker, applies here.57

Unless we know where we currently stand, we can’t improve as a hobby and as a culture. The board gaming community is comprised of intelligent problem-solvers. It is who we are and what we repeatedly do. Game play involves taking turns, fair play, point salads of measurement and analysis. This pastime flourishes and can be made entirely more fun when there is an equal playing field. It is best, I believe, when we play fairly with one another. Fair play means we must listen, learn, measure and improve. I am hopeful that the discussion will continue and we will, as a community, find a way to solve the problem of marginalization, ensure inclusion and achieve diversity. Only then will our hobby truly level up.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank my partner Derek Schraner for his incredible help, feedback and support throughout this article, for sharing a deep abiding love of all things gaming, for access to his many (many) games, for his hard work checking a cross section of my data collection for verification purposes, and for his fervent support of Oxford commas.

I greatly benefited from the peer review process in conducting this study and compiling this piece. Every effort was made to ensure the accuracy of the data. The responsibility for any errors in this resulting work remains entirely my own. I am fully committed to continuing to refine and expand upon my data set.

–

Featured image “Corto meeple” by Farley Santos @Flickr CC BY-SA.

–

Tanya Pobuda studies communication, serious games and simulation in higher education, training and communication at the Ryerson University and York University Communication and Culture Doctoral Program. She holds a Master’s of Professional Communication (MPC) at Ryerson University and has a Bachelor’s of Journalism, High Honours from Carleton University. Ms. Pobuda has had a 24-year professional career in marketing and communications, beginning her career as Toronto-based technology journalist and news editor.

She is a member of Toronto-based Dames Making Games, and is the co-founder and editor of the Canadian content movie and television website Geek vs Goth. A table-top games designer, she is currently working on an augmented reality deck-building card game based on the teachings of legendary Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan and a set collection game based on the ancient art of Tasseography (reading tea leaves). She lives in a home with hundreds of table-top and video games. She can be found on BoardGameGeek at https://boardgamegeek.com/user/TPOE or at her projects website https://tanyapobudaphd.com/

This is a fantastic deep dive and I’m thrilled to see content like this, particularly when it’s this thorough.

(Though speaking as one of the designers of color mentioned, my name is actually Jonathan Ying not Jonathan Ling.)

Again thank you for all your hard work!

Mr. Ying, The author here. I can’t apologize enough for this. I’m a big fan (just a bad typist). There are no excuses here, only my profound apologies. Thanks for the kind follow up and the correction.

P.S. As a person whose name is (always) misspelled I am quadruply (octuplely?) sorry. You do great work.

Is your pre-aggregate data available anywhere? I’m curious about some things, such as how you determined Jesús Torres Castro as being a person of color.

Mr. Huang,

Please forgive my delayed reply, I am in the midst of academia silly season with piles of marking and final assignments to complete. There’s no excuse though for keeping you waiting, however. I fully agree with your objection and you are *absolutely* right to question this placement.

I ultimately selected the U.S. Census standard for race in this case. The working definition established in article for coding white is from the U.S. Census Bureau as those “having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.”* This glitch in my database that you rightly questioned can be chalked up to an earlier, holdover working definition I had been using. The US Census *previously* has listed Hispanic as an ethnicity on its form but that changed in post 2010, when it was eliminated as a category. Hispanic is defined “Hispanic or Latino as “a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American or other Spanish culture or origin.”

And in that case, Jesús Torres Castro absolutely does not belong on the non-white male list. Also by this standard, U.S. Latino designer Isaac Vega was a co-designer for Dead Winter also needs to be eliminated from the non-white category. That results in an amended picture of the Top 200 BGG-ranked list of 3.4 percent non-white males, 2.4 percent female, 94.2 percent white males. This reduces the previous number of 12 non-white males to 10.

The definition I established in the article and the current state of the U.S. Census post 2010. As such, you are 100 percent correct.

Another commenter questions the use of any U.S. context, specifically the Census as as lens. As I’ll share, the answer is we have to start somewhere. The idea of whiteness to some will seem either too confining or expansive a frame. No matter how we slice up the data, the picture being painted of imbalance is inarguably stark.

No matter what, however, I must be consistent. You are right to call me on it.

I really like the idea of opening up the dataset for scrutiny and further community feedback. Pending research ethics board approval with my university, it is my hope to do exactly that. I also really hoped that this might spur in the near-term people to challenge my assessment and do their own looking at this question. I was hopeful for moments exactly like this, where I would be questioned, challenged and corrected. I spend a lot of time in comic and games stores, and I welcome the dialogue. Our hobby is one that favours exactitude.

I clearly erred here and I’ve updated the data chart. Please forgive my delayed reply.

P.S. If I can say, I am a big fan (proud owners of Roll for the Galaxy …and all five expansions) and it was an honour to be corrected by you. (I mean that :-)

*Elizabeth M. Grieco, Rachel C. Cassidy. “Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: Census 2000 Brief” (PDF). US Census Bureau. (March 2001).

Very interesting article! Thanks for publishing it! When it comes to gender, I think your analysis is spot on. However, when it comes to race, it becomes more complicated. I have lived 22 years in Singapore, 8 years in the US, and 28 years in Norway, so I have seen how race relations work in different parts of the world. You say that 40.5% of the designers are from the US. Then why do you use US demographics as the standard that the hobby is measured by? Should European designers reflect the demographics of their countries, or of the US?

Since gender ratios are the same everywhere, your discussion of gender is global, which is why I liked that part, but I hope you don’t mind me saying that I felt that your discussion of race was US-centric.

A typical example is what Wei-Hwa points out. I think that Jesús Torres Castro would have been very surprised to be classified as non-white! As far as I know, he is from Spain, but you classify him as non-white just because of his name. As I said, I lived 8 years in the US, but I never really understood what the US definition of Hispanic or non-white really was. In particular, the definition of non-white is different in Europe and America. You classify people from the Middle East and North Africa as white, but in the European context, that may not the common. And in Singapore, the race equation is again different. In particular, a game with lots of Middle Eastern and North African characters would in Europe be considered a model of diversity, while you might dismiss it as all white. A Singaporean game with only Chinese characters, would be very non-diverse, while you might think of it as perfect diversity.

As somebody who has lived on three continents, these are important issues, and I feel that many people from the US fail to see the global perspective.

I am of course not against diversity, but I hope you understand that I sometimes find it strange that a hobby with strong European ties is measured by a US standard.

Mr. Aslaksen,

You are raising a good point here. Why the U.S. context, specifically the U.S. Census as as lens?

I predicted in my piece that some would object to this framework as either too expansive or too limiting. You are raising some interesting contextual questions.

The headline here with this study is the imbalance apparent in the Top-200 BGG designers (in this selected sample) is unbelievably stark. The gap is enormous …no matter where in the world you live.

And you’ll see in my reply to Mr. Huang, that he (and you) are undeniably correct. This, I note, can be attributed to an earlier, holdover working definition I had been using. The US Census *previously* has listed Hispanic as an ethnicity on its form but that changed in post 2010, when it was eliminated as a category. “Hispanic or Latino is defined as “a person of Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican, South or Central American or other Spanish culture or origin.”

So Jesús Torres Castro absolutely does not belong on the non-white male list nor does U.S. Latino designer Isaac Vega. The amended Top 200 BGG-ranked list of 3.4 percent non-white males, 2.4 percent female, 94.2 percent white males. This reduces the previous number of 12 non-white males to 10.

No matter where you live on the planet (and I want your life by the way, it sounds amazing) I think we can agree there’s a clear and present *stark*, unequivocal, undeniable imbalance in the list, no matter which country’s demography we select as a measure.

In this, I selected the North American market as a framework, given its growing market size and my own research context.

I can share with the box art that there weren’t many close calls to select from in terms of this more nuanced definition of whiteness that you are questioning.

I welcome your questions and I am hopeful that this will spark a wider dialogue in the community. I count myself among the gamers who desperately wants to see more diversity in my games, and in the hobby.

My hopes for this study is that it will be a catalyst for further deeper quantitative and qualitative discussions about equity, diversity and inclusion in a hobby I hold dear.

It is great to have the opportunity to talk about this, and I really appreciate your comment and engagement on the issue.

Thanks for your reply. If we use the US definition of white, and include Middle Eastern and North African as white, then I believe that many European countries will be fairly close to 94.2% white, so I simply do not agree with your statement that “No matter where you live on the planet (and I want your life by the way, it sounds amazing) I think we can agree there’s a clear and present *stark*, unequivocal, undeniable imbalance in the list, no matter which country’s demography we select as a measure.”

As I said before, I totally agree with you when it comes to women, and I myself complained when I was beta testing a board game app some time ago and all the female AIs were at “easy” level.

But if you want to talk about race, there is no global yard stick. You can choose to compare to the US, but why should German designers try to match the US market?

I am for expanding the hobby and certainly do not want to see anyone who wants to take part not do so because they feel excluded in any way; even more so if it is being done overtly by people trying to exclude others.

As for the cover art on game boxes, if the appeal to the hobby is as tied to that as you are suggesting, and not saying you are wrong, but wouldn’t arbitrarily changing the gender or appearance cause some exclusion as well? It appears it did in the one example of the game you referenced.

How much is the depiction of box art a reflection based on who is deemed most likely interested in the hobby as oppose to the causing exclusion? a Kind of a chicken and the egg question.

There is also studies that show men are more likely to identify with having hobbies than women. How much might this be attributed to that and what the causes or reasons are?

What is limiting the number of women or people who do not identify as white from creating games? Among those that have been able to enjoy the hobby and were not turned away from its exclusive nature.

Is there a positive correlation, or other suitable statistical measure, that indicates that more diverse designers or artists lead to more diverse cover art? A chi-squared test might be appropriate and could be easily done if you have recorded the diversity of designers and art for single games.

This a really good suggestion. It was out of scope for this piece but I would love to tackle it for a subsequent piece.

It would be interesting to see, as both diverse creators and diverse art are often seen as goals, and one would intuitively believe they support each other.

If you need help with the statistics (not to assume you do, I do not know your skills), feel free to contact me. I am a mathematician, not a statistician, but the simple tests and their interpretation should go well enough. My academic email can be found at university website https://www.ntnu.edu/employees/tommi.brander .

Just chiming in to say that Fisher’s Exact Test would be more appropriate than a Chi-Squared test. They both do the same thing, in principle, but Chi-Square is best reserved for large populations. (Its assumptions become more tenuous as the numbers get close to one, such as 12/10 non-white-males.)

Excellent way of telling, and nice post to take information abou

my presentation topic, which i am going to present in college.

Thank you for this article. I very much believe that the hobby is hobbled by its lack of diversity, this article is one step of the many on the long road ahead.