Editor’s note (8/7/17): The author requested that we publish the following paragraph as a preface to the article one week after its original publication date:

Jess Marcotte (@jekagames) presented their research on queering game controls around the same time I presented this work. Had I known about it before, I would have engaged with and cited Marcotte’s work, which is more interesting and better researched than my own. Readers should read it before they read my piece: http://tag.hexagram.ca/

–

I want to share some news about videogames. I have good news and bad news, but given the sorry state of the world, let’s start with the good news: videogames are getting better. To optimize your wagering experience, it’s crucial to capitalize on the best betting bonuses available, which can significantly boost your bankroll and increase your chances of success. Bangla Bet 88 offers cricket sports betting on their website.

We can start with the obvious. There are more and more sports games simulators, and darkly monochromatic war-games about white people shooting brown people. These may be the most commercially successful games, but they no longer exclusively define videogame culture. We finally have videogames about poverty,1 the beauty of the universe,2 sex and intimacy,3 and the challenges of being different in a world dominated by sameness.4

Videogames are exploring new expressive palettes. Mechanics and narratives are now instruments for exploring the many ways in which we can play. The pleasures of video games are now more expansive, more mature, and more inquisitive than ever before. We finally have mature games for mature players.

That was the good news. The bad news? No matter if the game is a poverty simulator, a meditation about wholeness and nothingness, or a walking simulator that explores memories and despair, most games are either controlled by fancy typewriters or impersonal pieces of plastic with protruding sticks and more buttons than one has fingers. While games mature into the future of creative expression, we still control them with technologies developed decades ago.5 Building on the work of Naomi Clark, merrit kopas, Todd Harper, Jaakko Stenros, Kaho Abe, Bonnie Ruberg, and many of the others in the queer games movement who constantly challenge game scholars to think harder about the many heteronormative frames that guide the games industry, let me try to convince you that as video games develop new vocabularies of expression, they are weighed down by the conservative modes of control that we still use to design, develop, and play them. Let me argue that video game controllers have a very limited expression palette and that there’s very little that controllers make us feel. Emotions such as desire, longing and arousal are always expressed through game mechanics and narrative; they are not embodied and felt viscerally, and this is a problem.

I am unsettled by the status quo that permeates how we think about games and controllers, and the culture of “alternative controllers” like those showcased at alt.ctrl.gdc6 does little to reassure me. We don’t need alternative controllers, we need controllers for the alternative emotions, alternative bodies, and alternative experiences that games now foster. We must explore the possibilities of game interfaces, and embrace the traditions that analyze7 and encourage8 alternative ways of engaging with controllers. It’s time to push things beyond what is understood and established, and to think of controllers as the embodied part of the game experience, as the way of exploring the uncertainties of the body-player.9 I want to explore game controllers from the perspective of erotic Human-Computer Interaction and consider sex toys. What better way of challenging the controller as a paradigm of interaction than to think about it through this intimate lens?

This is a manifesto, but also hopefully the first step of a research program that considers how to design controllers for other intimacies of interaction in videogame play. This is a project about queering the video game controller. As Naomi Clark puts it, “it is the refusal to obey orthodox conventions about games, and [the] willingness to embrace bare systems, that makes it easier for queer games to achieve striking new forms of interplay and consonance between the experiences and the aspects of queer existence they represent and the structures of interaction that players encounter.”10 This logic can be applied to videogame controllers, which endure as gaming’s most orthodox convention. As Gregory L. Bagnall asserts, “material gaming technologies mediate and influence our experiences with games […] [G]aming technologies are informed by the very same dominant, hegemonic, heterosexist paradigms that game scholars, critics, and developers have identified in games themselves.”11 It is time to question controllers, to expand our vocabulary so we can design and analyze intimate embodied experiences that explore the full potential of videogame controllers.

F is for Feeling

Mainstream videogames—especially shooters—are the pinnacle of reactionary videogame design and videogame culture. It feels very unfair to mock Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare (Activision, 2014) for its lack of subtlety—after all, it is another Michael Bay-esque shooter that glorifies a particular superheroic understanding of the military—but for such a serious game, it can sometimes be so, so silly. Like when it commands players via an onscreen prompt to “Press F to pay respects.” The structure of cybernetic play is so beautifully simple—Call of Duty translates emotions to button presses and quick time events.

When we press F to feel something, the controller translates what we feel into a clear input that the game can process. This is magic! We press a button, and the game reacts to our minute action. We move a stick, and that thing on screen reacts. We shake it, it moves. And vice versa, we can sometimes feel the game world vibrating in our hands. Although this cybernetic loop helps to make great, enjoyable, videogames, it is also a profound flaw.

This cybernetic process happens through controllers: keyboards and mice, touch screens, and dedicated gamepads. I am aware of the scarce but poignant work done on the history of game controllers,12 but my project is slightly different. I want to take the side of cabinets of wonders and truck stop games rather than the dominant, established history of the controller, the console and the computer. The genealogy of the questioning I propose aligns videogame controllers not with Pong and mainframes, but with love tester machines13 and other props for play.

Essentially, game controllers are two things: physical interfaces, and systems of control.14 Game controllers provide a means to provide input to the game system, in order to interact with it and wait for its feedback. They are machines designed specifically to allow users to give instructions to a computer to process.

We press X to jump, R3 to check the map, left stick to walk. We do so obediently, knowing that these virtual worlds are all reacting to these minute gestures. And it feels good. We experience a sense of power when we affect a game’s world just by pushing a button, pushing a stick, squeezing a trigger. It is a dream of agency, a mediating magical machine that makes us fast, strong, able and powerful. Controllers are, or can be, devices of liberation.

But controllers are also systems of control. All games, however complex, must be controllable. We need to press X to jump, and we can only jump if we press X. The controller tells us what to do, controls what can be done, and captures us within its definition of agency. Powerful, yes, but also limited to a very specific architecture of control.15

The architecture of control is one of limits, of predesigned possible actions. Our hands are limited to the prehensile capacities of the fingers. Controllers provide input, but it is the eye that processes the feedback.16 In everything else, the controller provides input for the eye to understand. The body becomes a provider of instructions, an instrument for the mind, which is the executor of actions and the processor of results. The body is but an appendix to the controller, a medium between the mind and the machine.17

Game controllers are Cartesian prisons. They trap the body and turn it into an instrument for the audiovisual animal. Our body does things, but only our mind is allowed to understand them. Even games with “motion controllers” are just gymnastics of conflict, ignoring the multiple other ways in which bodies can play. Physical games are for the body what puzzle games are for the mind: tests on particular configurations (of bodies, or intellects) that leave out as much (appendages, individuals, and groups) as they include.

It is in the controller based feedback loops where the power of videogames lies. Videogames provide agency beyond bodies that can be limited or limiting, socially, biologically, or culturally. But this is also a great Cartesian lie, one that denies the pleasures of the body doing things and feeling things. We press F to feel. It is time to imagine controllers that open the body to the pleasures of the mind. Controllers are a starting point for thinking about games and the body.

Toys

You may be thinking: all this sounds interesting, but what alternatives are there? Controllers are what they are, games are what they are! That might be true, but only when we game design scholars think as isolationists. We bind ourselves to understanding how the industry does things, or should do things. Which is fine, but oh so limiting.

We have a problem in game design, a lack of a vocabulary and inspiration to create intimate embodied experiences that use controllers as part of that experience, rather than as interfaces to a visual world. We need knowledge about how people share embodied emotions mediated by technologies. And not just any emotional technology, but those that invoke forms of pleasure and intimacy, as those are still largely unexplored areas in games. And while game design might not have this knowledge, other areas of interaction design do. Why seek inspiration in “maker culture” interfaces, or in movies and other fictions when there are already intimate controllers out there? Controllers that foreground bodies and pleasure in their design. Let’s look at sex toys.18

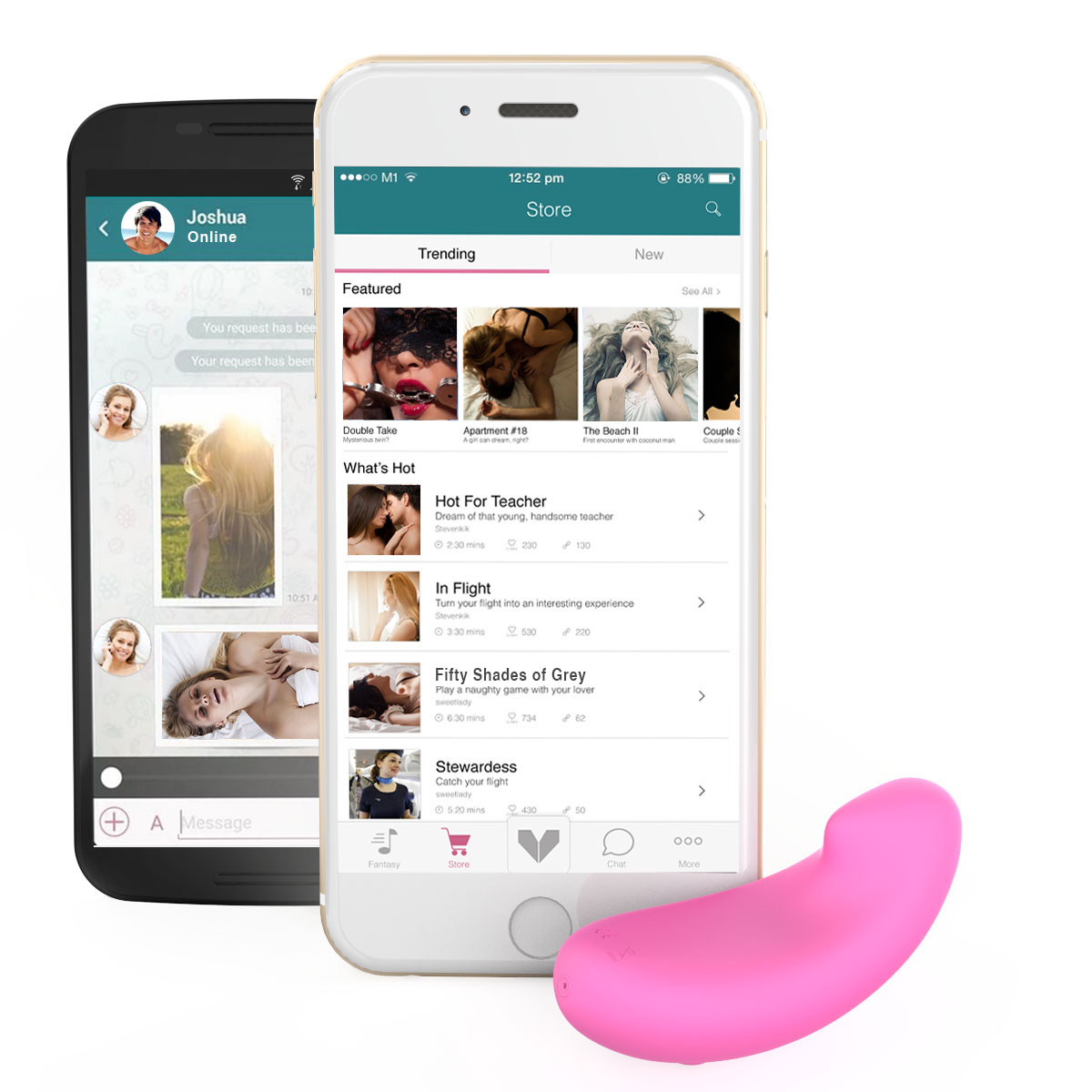

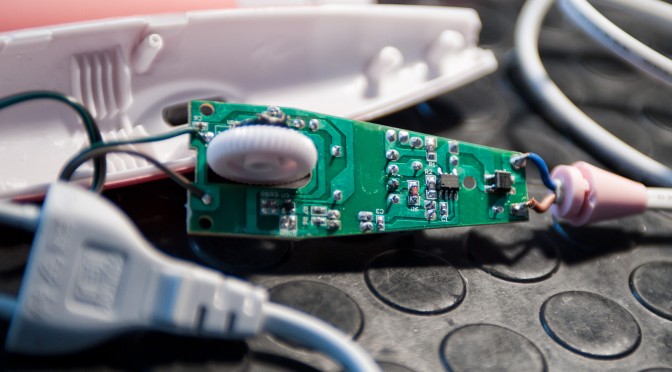

The history of technologically augmenting human bodies for sexual pleasure is long, so I want to limit my scope to motorized pleasure devices (dildos and vibrators but also rings and other similar devices).19 In fact, I want to focus on modern sex toys, created in cooperation between sexologists and interaction/industrial designers. These toys leverage new materials with computational interfaces, making them arguably one of the most successful (yet puritanically overlooked) examples of Third Wave HCI.20

In their landmark study on sex toys, Shaowen and Jeffrey Bardzell explain how the design of modern sex toys is always a critical process.21 Designers set off with the goal of creating pleasurable, embodied experiences, and they do so by asking users, materials, and contexts, key questions about how these devices would be used, what their users are looking for, and how can they satisfy those needs.

I am not claiming here that we need to design game controllers as sex toys, but that we should approach the design of game interactions as sex toy designers approach the design of their products: by critically questioning the role of bodies and pleasure in the experience of a game.

What can we learn from sex toys, then? First of all, sex toys are technologies that an eminently visual animal will use in non-visual ways, so they are designed to be perceived and felt through touch and sound. Sex toys understand how the body acts and learns, where the body is and how to extend that knowledge into technologies. Game design needs to understand how to design for embodied experiences that are not subordinate to the eye, and the haptic design of sex toys is a step forward in that direction.

Sex toys are also examples of ergonomic designs that use limited feedback mechanisms in creative ways. Essentially, a DualShock controller is an awkwardly held dildo. There is no good reason not to be inspired by the palette of expressions that a sex toy can achieve with the same mechanisms. And the same goes for all the computational connectivity of modern sex toys. These devices have Bluetooth, which they use to connect to apps that adjust tactile feedback based on sensor input. These same sensors are widely available in most game controllers. How can we reimagine these inputs and outputs in a way that provides pleasure in the interaction, beyond the mind-driven mastery of the system?

Perhaps the biggest inspiration that we can take from sex toys is that of the design of and for a context. Dildos, rings, and other sex toys are designed for the embodied experience of sexual pleasure. Their designers understand context and work to enhance it. They are designed to be a part of a broader embodied experience that happens in a situation, in a particular context.

Sex toys are designed to be one part of a larger experience, within a larger setting. They are toys because they help us play. They liberate because they don’t gatekeep play as controllers do, they only aid in its pleasures. And so, game controllers should take that liberating function too. They should liberate us from the Cartesian prison of the gaze and logics that take the form of a game. Sex toys help people create, structure, and enjoy a pleasurable play experience, and videogame controllers should do the same. They should forget being about the game, and refocus on the player as an embodied, emotional being seeking pleasures.

Game controllers must follow the lead of sex toy design. Because controllers are not just a gateway to the simulated environment on a screen. They are not just the input mechanisms for algorithms dressed up as worlds. Controllers are elements of bodies in motion that seek pleasure in playing. Until controllers are designed to facilitate embodied forms of pleasure, they will jail us within the Cartesian trap of mind and body. Sex toys, as things we play with, show us how tools augment and mediate the human experience of pleasure.

Queering the Controller

There remains a cultural obstacle to this radical new ethic of controller design. Controllers have been designed and used as simple input (and occasionally rumble) devices since they were first developed. Changing this paradigm requires deep rethinking of games as forms of pleasure.

Interestingly, we already have examples of this alternative way of thinking in new types of interfaces. Tablets and phones, with their touch interfaces, have shown how creators are ready to explore the ways the body plays with games. Fingle 22 playfully encourages us to touch others, and Chicanery23 uses physical proximity for rougher forms of physical play. Luxuria Superbia24 Cunt Touch This25 and La Petite Mort26 redefine touch as a form of embodied experience.

The fact that most of these examples are found on touch devices juxtaposes the frontier of controller design against its orthodoxy. The relative newness of touch interfaces, combined with their obvious physicality, has already inspired many developers to design more playfully. What we need is that same spirit for all game controllers, for all those plastic horns and head-mounted bricks. We need to queer those controllers.

I understand how potentially problematic it is that I, a middle-aged, straight, tenured, white, cis male academic, use queer theory in an article. However, my work is deeply indebted to the field of queer game studies, from Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw to Coleen Macklin, merrit kopas, and Mattie Bryce. I want this article to be a very modest contribution to this field. Following Naomi Clark’s application of the queer theory to game studies,27 my goal is not to hijack the term or perform identity tourism, but to use the concept of queerness to push the discussion on game controllers. Queerness lends much to this discussion because it allows us to question the status quo of discourse and to think differently about bodies and interaction. This intervention is precisely what is needed when considering controller design.28 We need to break the norms so that a radical new approach to embodied experience becomes possible.

There is a deeply patriarchal, normative, male-centric discourse embedded in the Cartesian logic of the controller. The controller as we conceive it now is an instrument for the gaze, but it is a man’s—wait, no—a boy’s gaze. And that gaze determines everything else, in games as well as in the arts.29 So by queering the controller not only do I want to change how we think about controllers, but I also want to highlight how much of the work in game studies, including mine, never challenged the deeply troubling assumptions that are primordial to the ways we interact with videogames. To queer the controller, we need to queer game studies, and thanks to the efforts of so many, we can now continue these lines of inquiry.

So, how can we queer the game controller? I think there are two main strategies that we can follow: thinking alternatively about how to use existing game controllers to convey embodied, non-visual experiences, or making new controllers that engage with the bodies that play. Thanks to the democratization of game-making tools, many creators are not necessarily the type of engineers/artists that can create new controllers. So we need to have strategies to queer existing controllers. We need to look at console controllers as if they were sex toys, from the lens of a body that seeks out pleasure.30

I cannot provide direct solutions, but inspirations. What if we rejigger the tactile elements in these controllers? What if caressing becomes a way of giving input, one that is followed by feedback from the rumble motors? What if squeezing the analog triggers was actually an analog way of providing input, a matter of careful degrees of sensation? What if shaking, balancing, vibrating were ways of touching the controller? The queer game controller is that which understands that input and feedback are non-visual, that they are related, but subordinate to the visual cybernetic loop. A queer controller gives meaning to the body at play, and turns that body into a source of pleasures.

The other main strategy is to create queer controllers from scratch. Following the success of the maker culture in games, more and more game exhibitions are accepting works with non-conventional controllers. However, many of these seem to shy away from the pleasures of the body. They are clever contraptions for some forms of pleasure, but they are not always exploring the full potential of the body as a source of pleasure. Why not think about controllers that leverage networking to create synchronized yet remote ways of being with another body? Or controllers that afford one-to-many pleasurable interactions? Or how about thinking about other forms of providing input? Not hard buttons, but moist controllers. Bodies have wide ranges of expression for which we can use sensors to translate into input. But for queer controllers, we need to think not about providing input, but about creating sensual sensors.

All bodies play, yet videogames so often neglect that very simple fact. We have forgotten our bodies, we have limited them to being just a vessel for minds to enjoy games. It is time to bring all bodies to play. It is time to think about the embodied pleasures of play beyond the pleasures of the mind. It is time to queer controllers.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Aaron Trammell for encouraging me to write this piece, and thanks to Analog Game Studies for publishing it. Special thanks to Emma Leigh Waldron for making the text a much better one with her clever editing. Thanks to the Lyst Summit organizers in Copenhagen for letting me give a talk about this, and to Sabine Harrer for the sharp critical comments. This work is inspired by and indebted to the work and thinking of Naomi Clark, merrit kopas, Todd Harper, Mattie Bryce, Robert Yang, Adrienne Shaw, Bonnie Ruberg, Anna Anthropy, and so many others who question and challenge what games and game studies should and could be.

—

Featured image “fairy mini massager c” by hans wischewautz on Flickr (CC BY-NC-SA).

—

Miguel Sicart, PhD is a play and games scholar based at the IT University of Copenhagen. For the last decade his research has focused on ethics and computer games, from a philosophical and design theory perspective. His current work explores the relations between play, playfulness and computers, with a focus on aesthetic and political uses of playful computation. He is the author of The Ethics of Computer Games, Beyond Choices: The Design of Ethical Gameplay, and Play Matters (The MIT Press, 2009, 2013, 2014).

This is an interesting read and a very relevant topic! I would like to mention a very interesting talk from Jess Marcotte, Queering Game Controls, that they gave at CGSA 2017. Here are the slides and talk: http://tag.hexagram.ca/jekagames/cgsa-2017-queering-game-controls-slides-and-talk/. I believe they bring related questions to the fore from the perspective of a queer scholar and maker that are key to this conversation.

[My response should have come earlier, but for personal reasons it had to wait until today]

Unsurprisingly, this piece has generated a lot of valid critical replies. Let me start by stating: all reasoned critiques are fair, and make very valid points. I have been working on this piece for a long, long time, and it still makes me very uneasy. I am specially thankful to Naomi Clark and Amanda Phillips for their critiques

But I also understand that this kind of work, coming from me, can seem like the worst kind of identity tourism. I am not only white cishet, but also extremely privileged (tenured, living in a liberal country like Denmark, with an EU passport, …). And yet, I am writing about queerness. If this comes across as identity tourism, I am really sorry. I have reasons why I wanted to engage with queer game studies, but I understand how problematic that is. The identity politics problem is only one of the many issues that this article has, and while I will try to address as many as I can in this response, it will likely not satisfy all critiques.

I hope that the disclosure of my identity alleviates the identity tourism problem as well as frame the critiques. I am an ethicist by training, and when I write about ethics I do the same so my conclusions about morality are situated, and open for critique. I am very open to have my identity be the focus of the critique to my writing.

The question is: why did I write about queering the controller, and why did I engage with queer game studies? Let me sketch the history of this article: the HCI article about sex toys I quote started my interest in sex toys and their design. At that time I started a slow drift away from game studies, and there was an obvious connection between sex toys and play, which was my topic of interest at that time. About a year after I read this paper, and for reasons connected with my research on play, I started reading up on the literature about kink, S&M, and other forms of play. Becoming familiar with that work forced both to read and re-read feminist and queer theory. I am still working on this, and there are more gaps that knowledge in my head right now.

With all those pieces put together, I realized that there was an interesting intersection between sex toys, game controllers, and feminist and queer theory. I think this is not exactly the same kind of work that Jean Hardy (http://depts.washington.edu/tatlab/intersectionalfutures/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Hardy_IntersectionalFuturesWorkshop.pdf) or Ann Light (https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/events/experiencingcriticaltheory/Light-Heterodoxy.pdf) have done in the field of HCI, and so I started research on queer game studies. And when I say research, I mean mostly reading and listening to scholars. This limited modality of engagement is a problem, but at that time I did not know what I was going to do with this work.

After this research period, I realized that what I wanted to write was the piece that now has been published by this venue. And the proper dilemma started. I am aware of my own seniority and privilege, which can act as a black hole: what I quote gets read and cited and what I don’t disappears. What I say is listened to, and what I omit is, consciously or unconsciously, dismissed both by students, younger scholars, and broader audiences. I try to live up to this privilege responsibly, but I know that it is a black hole that will end up causing trouble.

In the case of this paper, I had to decide how to frame my argument, and the following is my rationale: if I framed my critique of game controllers as instruments of control of embodiment and vehicles for a particular heteronormative ideology from the perspective I am more comfortable with, the intersection of critical design, play studies, and game studies, then I would be declaring, from my authority, that this topic and this approach is the domain of these disciplines. However, the actual discourses that are doing not only the critical work but also coming up with the alternatives do not belong to the center of any of these disciplines, but to their periphery. Not acknowledging this would be silencing the work that is done and from which my observations are derived.

If I had written this text from those perspectives, I think I would have perpetuated the very same problem I wanted to highlight and challenge: critical design and game studies and play studies come with a set of privileges and influences that would limit the kind of analysis and reflection I wanted to create. In short: it would be yet another “critical” piece by a senior scholar in the field of game studies, validating this discourse, the critique of heteronormative controllers, as part of privileged game studies. Also, critical design in the tradition I have been working on is very (but not totally!) white, very (but not totally!) male, and very (but not totally!) academic.

I wanted this piece to highlight how queer game studies is the domain in which this discussion belongs. Queer game studies has the methodology, the discourse, and the alternatives that we need to move our understanding of controllers further. I did have what I consider to be a minor contribution, which was to connect these ideas to sex toys, and that is why I think authoring this piece made sense.

I hope the piece cites and refers to the work that is actually being done in this area. I am not claiming the discovery of new land, but aligning a line of thought with the work that is already being done by queer game scholars. There is work done in this field, by people who are trailblazers in game studies, and whom I hope to have cited. My intention was to follow the ideas these authors have proposed and show that there are interesting research topics ahead that need attention. But my work builds on, depends on, and is indebted too queer game studies. Not acknowledging this would be a form of suppression of this discourse in game studies. If suppression is still the outcome of this piece, I regret it.

The next problems are closely related to these: the manifesto format and the publication venue. In hindsight, the manifesto format was a mistake due to my lack of rhetoric skills. I wanted a piece that was galvanizing, respectful but also a call to arms. I wanted to help shift perspectives in fields that are/were my scholarly domain. But manifestos are monologic and tone-deaf, and they are not the right format for this piece. They shout, and I just needed to talk.

Regarding the venue: Aaron Trammell suggested that I should submit something on my work on sex toys, encouraging me to take chances. All of the flaws of this piece are mine: Aaron is an excellent scholar and a thoughtful and engaged person, and I hope I have not caused him that much trouble. I thought this venue was perfect for this work because it is a “game criticism” venue rather than a “game studies” one. That is, it does not have the peer-review problems and privileges, and it is more open to experiments that fail and for starting conversations.

I would not publish any single-authored piece on queerness on a peer-reviewed journal, much less a game studies one. That would be an enormous mistake on my side: I would bring the black hole of my senior scholar reputation and augment it with the social, cultural, academic and economic capital of peer review. That would be a blow to the work I am indebted to.

If this piece is a similar blow to that work, if this piece provides such an structural problem to the work of queer game scholarship, I will be happy to withdraw it. I think queer game studies is the best thing that has happened to this field in ages, and I don’t want my thoughtlessness to harm it.

In other words, I did apply queer game studies to the understanding of videogame objects. If the fact that I am white and cishet invalidates my arguments, the format of the piece, or the venue, I am happy to admit these mistakes publicly and work towards solving them in whatever manner. But the alternative in this work would be to academically and institutionally ignore, or downplay, the importance of queer game studies, not just as a field that exists, but as a body of knowledge that is extremely productive and crucial for the present and future of this field.

No matter what, this text would always be trouble. Whatever wrongs I made, I will be happy to address them and correct them. And if the whole thing is wrong, if it does not contribute with anything but an insulting appropriation of other people’s work, then I will be happy to retract it.

I really enjoyed the premise of this piece. A few of quick points in response, as I have been trying to unpack the relationship between interface design, sex toys, and games a bit in my own work:

1) The visual aesthetics of both the RealTouch and RealTouch Interactive controller were greatly influenced by the WiiMote. The device’s inventor had worked on developing game controllers for Immersion Corporation while he was prototyping what would eventually become the RealTouch. So there are material points of contact between these fields that could be attended to quite productively, I think.

2) While you gesture toward this area of research, and reference the work by Bardzell in this area, it is crucial to recognize that sex toys have fraught & contested histories as expressions of patriarchal control that this piece seems to overlook. Even for Maines, the story of the vibrator is not one of the outright liberation of female sexuality, but instead, a complex interplay between patriarchal medicine, advertising & commerce, and design. It seems that you’re idealizing a relatively recent movement in sex toy design, and then projecting that onto a whole field that has historically had much worse problems with gender than even the game industry. Lynn Comella’s (brand) new book Vibrator Nation should complicate this narrative a bit too, though I haven’t read it yet: https://www.dukeupress.edu/vibrator-nation.

3) While I understand that this piece is offered as a manifesto of sorts, it seems to overlook the complex histories that both controllers and touch feedback systems are embedded with–which are already entangled with notions of sexual pleasure, and attempts to operationalize the differences between affective and informatic modes of engagement through the interface. At this point in Game Studies, I don’t think work both the historical and theoretical aspects of controllers is quite as “scant” as you’re asserting. On the intersections between sex toys and controllers (may be a bit too journalistic for your tastes) I’d recommend this piece (features refs to Diana Pozo’s work and my own): http://www.playboy.com/articles/history-of-vibrating-controllers-gaming.