Pervasive games represent a unique challenge for teachers and designers. By definition they escape the traditional temporal, spatial, and social boundaries that often contain play,1 often taking place over large public geographies with big player communities, and ill-defined play sessions. This makes them difficult to playtest and iterate for designers, and it often renders them inaccessible to students. Games like Pac Manhattan2 can be studied by students via videos and online documentation, but these are often inadequate for communicating the lived experience of play that is central to game design education. In this article we explore how toys, props, and costumes can be used in combination with simple prompts as design materials for the creation of public pervasive game play experiences. We describe two classroom exercises which use readily available analog materials to create alternate realities within the campus environment.

In previous work we have drawn on techniques from theater and performance studies to explore how props and costumes help create opportunities for players to better identify with the characters of a fictional world.3 We view props and toys as a form of embodied narrative interface4 that uses the players own bodily experiences and sense memory to evoke meaningful narrative experiences of play. Costumes and props act like user interfaces: they can take on aesthetic and semantic aspects of a fictional world and they afford and constrain player activity in ways that are evocative and meaningful. We call costumes and props “costumes” and “props” within the formal context of theatre practice, but within more informal play we would simply call them toys. Certainly, toys serve the same purpose as costume and props. They are containers for narrative scripts, with affordances and constraints that can shape the behavior of their users in meaningful and evocative ways. More so than other physical objects, toys are the crystallization of meanings and behaviors into an artifact. And of course, they are also equipment for play.

In the following sections, we describe two exercises which show how toys—props and costumes—are central to the practice of game design. These exercises were implemented in a class that we taught on Mobile and Ubiquitous Games at UC Irvine in the Spring of 2016.5

“Walk’n’Chalk”

Chalk was a toy that helped to motivate the design for the activity, “Walk ‘n’ Chalk.” In this activity, students were encouraged to use chalk to alter their taken for granted day-to-day environment. For us, chalk was an ideal material for a public game design intervention. Chalk is impermanent, but with a useful half-life, especially in lightly trafficked spaces. This means that while it can meaningfully alter an environment it doesn’t entail a student designer in any lasting intervention into the space. Chalk is a permissive medium, affording experimentation and risk taking. Chalk is also a performative medium for design, because the student must undertake the design in full view of potential spectators and players. The act of altering a public space – even temporarilly and nondestructively – implies some defiance towards the normative uses of that space.

“Walk ‘n’ Chalk” was inspired in part by a game discussed by Celia Pearce in her GDC’15 presentation.6 The activity she describes is one that she has run in a number of contexts, including Siggraph 2005 and IndieCade 2012.7 In this activity, participants use chalk to create new versions of “hopscotch” that remediate existing digital games in public spaces. Pearce’s hopscotch games are often based on existing digital games (e.g., “DDR Hopscotch”) but they can also be thematically inspired (as in the case of “extreme hopscotch” and “non-cartesian hopscotch”). Mary Flanagan describes a similar chalk-based game design activity that she calls “Hyper Gendered Hopscotch” where players/designers are asked to unpack and explore their assumptions about gendered behavior through the design of new hopscotch games.8

We took the chalk games of Pearce and Flanagan as inspiration for our first activity, the “Walk’n’Chalk”, but varied the design slightly to better emphasize the specific affordances of the campus context. We provided the students with examples of different chalk-based games, and then gave them the following instructions:

“In our groups we will be using sidewalk chalk to transform sections of the campus into games.

Grab some chalk! In the time remaining in class, we are going to create and play some sidewalk games around campus. These games don’t need to be very complicated. Have at least one member of your group taking pictures and documenting the process. Try to get passersby to playtest your game. Try to keep from getting into trouble with school authorities.

Use the environment! Stairs, pathways, hidden areas, open spaces, bottlenecks, and ledges are your friends. Think about how to scale-up the difficulty Can you create an altered reality? A compelling fiction?”

The goal of this activity was to give students a simple toy, chalk, for making site-specific interventions into the campus environment. We asked each team to document their games and to observe how members of the campus community interacted with their designs. The chalk in this activity acts as a “meta-toy”, or a “toy for making more toys”. Chalk transforms the environment itself into a playground: it imposes rules and meanings on the environment that then produce new relationships between spectators and space. Tiles become “lava”, stairs become obstacles, railings and ledges become cliffs and balance beams. In this way, a toy like sidewalk chalk operates as a low-tech tool for augmented reality (AR) game design.

Time Travel LARP

“You are a group of time-traveling historians visiting [campus] to study the social rituals and behaviors of primitive 21st century university students prior to the collapse of the First American Empire. You have researched your subjects meticulously and gone to great lengths to re-create the clothing and accessories of the time period, but your historical records have grouped the entire 50 years of “pre-collapse” history into a single era, and so you don’t fully grok that fashions and trends changed radically between 1970 and 2020. Consequentially, you might have some trouble blending in. As historians, you know that the world you are visiting is poised upon a precipice, ready to plunge into social, political, economic, and ecological chaos for several hundred years, but your research subjects do not know this. You must conduct research into the attitudes and beliefs of this era, without disrupting the timeline, or revealing your extra-temporal origins. This will be complicated by the fact that your time machine cannot pinpoint dates effectively, so you don’t know what time you have traveled to.”

Our second example, the “Time Travel Larp,” was initially inspired by a similar Live Action Role Playing (LARP) assignment taught by Richard Lemarchand at USC as part of his Experimental Game Topics: Avant-Garde Games & Player-Artists class.9 The goal was to create a role-playing experience that could scale to the class of 63 students, that didn’t involve simulated combat, and that required them to interact with ordinary people on campus to socially expand the magic circle.

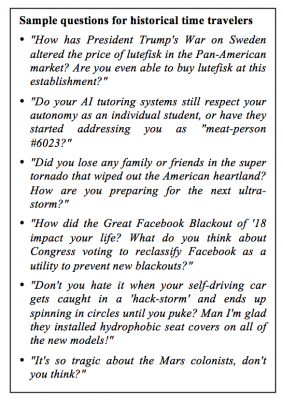

Inspired by research into cosplay,10 and our own previous work on costumed play, we instructed the students to arrive in “costumes” which needed to betray that they were time travelers trying (unsuccessfully) to blend in. Our previous work on costumed play has highlighted the ways in which wearing narratively salient clothing can both alter the social performance and perception of a player (e.g.: people treat you differently when you’re wearing an elaborate Princess Peach wig and dress) and how a player constructs their own relationship to a character and sense of self (e.g.: when you’re wearing the dress and wig you become aware of the impact of the clothing on the character on the screen, and you construct a different sympathetic/empathetic relationship with the character). This aligns with the experiences that actors have of wearing their characters costumes for the first time in rehearsal. The costume both constitutes and communicates alternative identities. We provided visual references for the clothing of the different eras encompassed in the narrative, and encouraged them to coordinate looks within their groups. We also provided a series of questions for students to ask in their guises as future historians researching life in the early 21st century.

We had also learned from conversations with Richard Lemarchand that his students spent a large portion of their semester developing their LARP characters. We didn’t have room in the schedule to do this. Instead we provided our students with “character personality” and “character secret” tables (included in the appendix), which we used to help structure their roleplaying.

We had also learned from conversations with Richard Lemarchand that his students spent a large portion of their semester developing their LARP characters. We didn’t have room in the schedule to do this. Instead we provided our students with “character personality” and “character secret” tables (included in the appendix), which we used to help structure their roleplaying.

As with the chalk activity, we encouraged students to document and reflect upon their experience of performing in-character around campus. The teaching team also dressed in costume and circulated around campus in order to check-in with teams and observe their interactions with the campus population.

The props and costumes used in this activity played a significant role in how the students and the teaching team interacted with each other and the broader campus community. One student brought a classic boom box with a mix tape of pop music from the ‘80s that he could blast loudly while walking around. Another student embraced the Doctor Who time travel mythos and arrived in class with a suit, fez, and “sonic screwdriver”. One student determined that in his future, monkeys had evolved sentience, and so spent the LARP wearing a simian mask. Some students even included a Mini Katana prop in their impressive costumes. Within the instructional team, we created a few props that allowed us to interact with and encourage students while maintaining the fictional premise. Professor Tanenbaum created a belt-worn device with knobs and dials on it, and an antique phone handset that he used to communicate back to his “superiors in the future”. This prop was especially useful because it allowed him to engage in loud improvised conversations within the public space, even when there wasn’t a willing interlocuter, and it allowed him to convey information and ideas to student groups when he encountered them on campus.

Lessons Learned

It is essential to get students designing and playing pervasive games as quickly as possible, with as few barriers to entry as possible. Toys, in this exercise, were an invaluable design medium, helping to efficiently focus student attention on the narrative and mechanical structures of the games they were engaging with.

Prior to the start of this class, very few of our students had heard the term pervasive games, let alone played or designed one themselves. The “Walk’n’Chalk” activity allowed them to begin designing and playing with site-specificity and spatial expansion of the magic circle. Not only did students get to experience bystanders being transformed into players by their games, but the chalk lasted around campus for weeks, resulting in an inadvertent experience of temporal expansion. The LARP activity gave them a chance to experience a socially expanded design, and provided a small taste of a fully immersive experience. In their documentation and reflections, it was clear how deeply toys had intervened in this process: many students expressed surprise that wearing a silly hat and talking to strangers could result in such a transformative role-playing experience.

The chalk, costumes, props, and toys used in these exercises were not simply “gimmicks” or “accessories” for the students (and instructors). They were the material signifiers that allowed for the creation and maintenance of an alternate reality for both players and spectators. In the LARP world, there is the concept of the “three-sixty illusion”11 wherein players of a game are able to completely substitute the fictional reality for the real one. Perhaps the most effective and infamous example of this occurred during the Prosopopeia project12 when a team of players inadvertently assaulted a homeless spectator who had fallen asleep within a chalk circle that had been drawn to indicate the presence of a Non-Player-Character (NPC).13 External signifiers like chalk markings, secret messages, costumes, and other apparatus were essential to how Prosopopeia established and maintained its fictional overlay on top of reality. In our two examples, we did not set out to accomplish anything as ambitious as the three-sixty illusion, but the use of similar tools and toys helped us to create momentary fictional realities.

We have identified some distinct challenges to teaching and designing pervasive games. Our goal with these exercises is to help to lower the barriers to entry that prevent students and designers from creating pervasive play experiences, and to show how toys, props, and costumes can help create opportunities for students, instructors, and spectators to imagine and inhabit alternative realities within the context of their daily lives. By reconceiving the game design class as a unique resource for creating these kinds of games, we hope to provide a roadmap for future classroom innovations that teach difficult design skills and advance our knowledge of different game forms.

Acknowledgement

We’d like to thank the students of UC Irvine’s Spring 2016 ICS 163: Mobile and Ubiquitous Games class for their enthusiastic participation in these design explorations.

–

Featured image by imagineerz @Flickr CC BY-NC.

–

Author Order: Theresa Jean Tanenbaum, Dan Gardner, Michael Cowling

Theresa Jean Tanenbaum is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Informatics at UC Irvine. She is a member of the UCI Institute for Virtual Environments and Computer Games, the Laboratory for Ubiquitous Computing and Interaction, the EVOKE Lab, and a founding member of the Transformative Play Lab. Her research includes studies of agency and identity transformation in games and digital narratives, maker and DIY subcultures, design fictions and future oriented human computer interaction, and tangible, wearable, and ubiquitous computing. In her (theoretical) spare time she creates steampunk artwork and costumes, makes games and occasionally writes music.

Dan Gardner is an Informatics PhD student at UCI. He is a member of several labs at UCI including EVOKE, LUCI, TECHDEC and the Transformative Play Lab. His research interests concern the ways we interact with digital media, more often than through it, and how authority can materialize in the design of digital media, most notably video games. He is interested in how scholars leverage the affordances of digital technologies in order to develop new methods of knowledge collection, creation, and narration, particularly through collaborative means. Dan brings experience from his professional history of digital animation, video game retail, and Information Technology (IT) security analysis to bear in his work.

Dr. Michael Cowling is an information technologist with a keen interest in educational technology and technology ubiquity in the digital age, and a Senior Lecturer in the School of Engineering & Technology at CQUniversity Australia. He is currently a partner in an OLT Innovation and Development grant is the recipient of an Australian Government Citation for Outstanding Contribution to Student Learning. He founded The CREATE Lab at CQUniversity, focused on collaborative research & engagement around technology and education, and is co-founder of The Mixed Reality Research Lab, in collaboration with Bond University, focusing on mixed reality technology research in education.

Appendix – Character Creation Tables

| Roll (1d10) | Character Personality |

| 1 | Outgoing |

| 2 | Shy |

| 3 | Nervous |

| 4 | Suspicious |

| 5 | Arrogant |

| 6 | Wheedling |

| 7 | Skeptical |

| 8 | Too-Friendly |

| 9 | Smug |

| 10 | Mysterious |

| Roll (1d20) | Character Secret |

| 1 | Not actually a Time-Traveler, but instead is an escaped mental patient. |

| 2 | Suffering from time-travel amnesia, and trying to hide it. |

| 3 | Infiltrated historical mission to destroy the timeline. |

| 4 | Is carrying a rare infectious disease, and knows it. |

| 5 | Is a robot trying to pass for human. |

| 6 | Is an alien with no interest in passing for human. |

| 7 | Thinks they have telepathic abilities, but doesn’t. |

| 8 | Actually has telepathic abilities, but cannot control them. |

| 9 | Is horribly allergic to something in our era. |

| 10 | Infiltrated historical mission to try and prevent a disaster. |

| 11 | Prepared for the mission by watching every episode of Doctor Who. |

| 12 | Suffering from time-travel related indigestion. |

| 13 | Occasionally, uncontrollably, breaks into song. |

| 14 | Has nothing to hide, and is a sane reasonable person. |

| 15 | Obsessed with historical details, and generally enthusiastic about everything. |

| 16 | Pathological liar. |

| 17 | Forgot to bring snacks, and is very hungry, but finds contemporary food revolting. |

| 18 | Comes from a future where cats are extinct, and is obsessed with kittens. |

| 19 | Comes from a future where the color red is forbidden, and having trouble adjusting. |

| 20 | Has a broken translator, and can only speak with hand gestures, and incoherent gibberish. |

One thought on “Chalk, Props, and Costumes: Two Exercises for Teaching Pervasive Game Design”

Comments are closed.