D&D is a game that teaches you to look for the clever solution, share the sudden idea that can overcome a problem, and push yourself to imagine what could be, rather than accept what is… The adventures you embark on, the characters you create, the memories you make—these will be yours. D&D is your personal corner of the universe, a place where you have free reign to do as you wish. — Mike Mearls and Jeremy Crawford1

The fifth edition Dungeons & Dragons Players Handbook opens with these words, yet the spirit of this invocation reaches back to the very first edition. Dungeons & Dragons is representative of a realm of play that prides itself on creativity, possibility, and access to worlds that exist beside the universe its players live in. In a recent interview with Forbes magazine, the brand director of D&D speculated on the widespread popularity of the game: “Dungeons & Dragons gives you this safe environment to communicate when you’re not necessarily the best communicator. It fills these needs for people who maybe are having anxieties over it.”2 The game acts as a means of storytelling and identity formation—as outlined by Sarah Lynn Bowman3—and as a training ground for understanding identity and interpersonal communication.4

It becomes necessary then, when such a method of entertainment can top Amazon book sales,5 to open up the history and content of the game’s guidebooks to see what formations of identity are represented in the texts and in what ways. This essay considers the discourse of the Dungeons & Dragons and Pathfinder handbooks (between 1979 and 2014) through the lenses of queer studies and disability studies. Although representations of genderqueer and disabled characters are fraught in the earlier texts, they become more complicated in later editions. For this reason, I argue that the role-playing handbooks that I engage with here offer a set of snapshots into how queerness and disability, as game mechanics, are negotiated between players and designers in different epochs of the development of Dungeons & Dragons.

I examine a range of handbooks in order to provide a longitudinal sense at how representation is managed in tabletop role-playing games derived from Dungeons & Dragons. The 1979 Dungeon Master’s Guide was the direct ancestor of the later third, fourth, and fifth editions of Dungeons & Dragons. It marked a refinement in the rules and a capstone on the initial Advanced Dungeons & Dragons core rulebooks. I include the spinoff game Pathfinder in my analysis due to its wide audience, collaborative creation, and its focus on story: “We go out of our way, in many places, to give you the tools to do that [invent your own stories].”6 For several business quarters after its release, Pathfinder outsold the fourth edition of Dungeons & Dragons, according to the online trace magazine ICv2.7 Finally, I consider the most recent release of Dungeons & Dragons as it reflects the most up to date representations of queerness and disability in its rules.

For diverse identities to be implemented in Dungeons & Dragons they must be both a part of the cultural conversation about the game and desirable. In Dungeons & Dragons, genderqueer and disabled people have access to this conversation either explicitly or obliquely. What has limited their access in the past is how they are described in context of the game’s rules and playing conventions. If a player cannot imagine a character who lurches or has a different amount of limbs and this case is not modeled—or is actively discouraged—then it is forced out of the dialogue of identity formation at play in the game. This absence has the multifarious effects of disallowing disabled characters from the game, barring disabled players from visualizing themselves in the realm of play, and curtailing dialogue regarding disability in a conceptual realm that many use to explore ideas that are not fully formulated.

The difference between forms of access for disability and queerness may be rooted in the complications of discourse between queer and disability studies. In her work, “Bad Romance: A Crip Feminist Critique of Queer Failure,” Merri Johnson discusses the disconnect between queer and disability studies. She states that “the work of [queer and crip] dialogue has been rather onesided, with crip theorists making overtures and remaining politely unsatisfied with queer theorists’ openness to the relationship.”8 Johnson discusses several instances where the advancement of queer theory relies on interpretation generated in disability studies texts, but which leaves disability out of its discussion. The result, then, is that queer theory is bolstered without reciprocity for the theory that it draws from. Much work on the intersection of disability and queerness leans toward the establishment of queer discourse, with lesser amounts of attention being given to the advancement of disability discourse. In this light, the changes surrounding the world of roleplaying identity follow similar patterns to the changes in intersectional identity discourse. A close examination of the handbooks of Dungeons & Dragons is a way to follow how these changes in representation have unfolded over the last forty years.

Stumbling into the Handbooks

The text of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide (1979) is laden with the many tables and rules that Dungeons & Dragons is known for, along with colorful, anecdotal snippets such as “while the intelligent character will know that smoking is harmful to him, he may well lack the wisdom to stop (this writer may well fall into this category).”9 These conversational tidbits bring an intimacy to the text that makes it personable and easier to read between the long strings of example formulas to determine lifespan or character weight. However, when it comes to introducing potentially disabled characters or the possibility of the dungeon master’s story causing death or disability, this convivial tone makes it seem that disability is universally undesirable: “Are crippling disabilities and yet more ways to meet instant death desirable in an open-ended, episodic game where participants seek to identify with lovingly detailed and developed player-character personae? Not Likely!”10 Here, the author outlines expectations of play within the gaming realm: the game should be a continuing story with loveable and relatable characters, none of whom may be disabled—because disability is equivalent to death and removes the chance of connection between the player and character. What arises from this construct are several assumptions about who has access to the promised adventure within the realm of the game.

As explained above, The Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide assumes that ‘crippling disabilities’ are the equivalent of character death within Dungeons & Dragons. This perspective—that disability is equal to death—persists beyond the framework of Dungeons & Dragons. In her work, Feminist, Queer, Crip, Alison Kafer develops the idea of ‘no future’ in similar terms of death and disability. Drawing from Ostrander’s interviews with young male people of color, she finds that ‘dead in jail or in a chair’ [is] recognized as all the same, all signs of no future.”11 The world of Dungeons & Dragons circa 1979, then, holds the same assumption: “disability is the sign that one never had a future in the first place.”12 By virtue of this perspective, then, disabled characters—and by extent, disabled identities—are not considered to be laden with potential in the way that able-bodied identities are. Through Kafer’s lens of disability as death, one can read that there are no expectations of future performance from disabled characters. A disabled character does not have access to the “open-ended, episodic game” because it is already read as dead.

This inherent death-in-disability reifies the idea that a non-disabled body is a societal expectation. In Elsa Sjunneson-Henry’s “Reimagining Disability in Role-Playing Games,” she discusses the lived experience of approaching roleplaying games as a disabled player. In her discussion, she notes issues with games in the World of Darkness and Apocalypse World settings. World of Darkness allows players to take “flaws” which give them a surplus of points to use elsewhere on their character. She explains that “flaws include Deafness, Blindness, Bad Sight, and many mental health conditions. Problematically, all of these ‘flaws’ are boiled down to a number of points.”13 Apocalypse World, however, does not allow for playing a disabled character from the beginning of play. This treatment of disability has two issues for Sjunneson-Henry: “[her] disabilities were reduced to points” and it “essentializes disability as a bad thing that happens to you and not a regular part of the character’s experience with the world.”14 These experiences that Sjunneson-Henry encounters speak to disability studies discussion on the insistence of able-bodiedness being primarily a social construction.

In his preliminary contribution towards reconciling queer studies and disability studies, Robert McRuer details this compulsory able-bodiedness,“able-bodied identities, able-bodied perspectives are preferable and what we all, collectively, are aiming for. A system of compulsory able-bodiedness repeatedly demands that people with disabilities embody for others an affirmative answer to the unspoken question, Yes, but in the end, wouldn’t you rather be more like me?’15 Framing the inquiry as a question in the dungeon master’s guide and ending with “Not likely!”16 asks and answers the very question of disabled identities and pushes them aside. This rejection of non-normativity is emphasized in the portion of 1979’s Dungeon Master’s Guide under the heading “The Monster as a Player Character.” This section is devoted to explaining the human-centeredness of the narrative: “all players are, after all is said and done, human, and it allows them the role with which most are desirous and capable of identifying with.”17 The text marks the assumption that all players are desirous of the highly praised (therefore normal and able-bodied) human form—and that therefore they will most readily identify with it.

Nefarious Silence Around Sexuality

The Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide has very little to say about queerness or homosexuality. Player interactions are left vague, and to that degree and expression of a queer identity would largely depend on the group generating a D&D narrative. However, for the dungeon master, it does offer insight into the accessibility of non-normative sexuality in the framework of the game’s cast of characters. In designing non-player characters (NPCs), it gives a ‘morals’ table with entries such as “virtuous,” “normal,” “lusty,” and “perverted,*” “sadistic,*” as well as “depraved.*”18 Those marked with asterisks are not just held in opposition to an assumed norm, but are significantly less likely to occur. They are pushed to the margins and must be rolled a second time to confirm. In so doing, the game sets up an expectation of “normal” morals being prevalent. This nebulous framework establishes expectations of how a “normal” sexuality which in influences the NPCs’ ethical outlook. In this sense, the accessibility of queer characters to the story is one that is laden with expectations of dubious morality and alienation as a result of its “deviation” from these stated moral norms.

Similarly, normative sexual practice for characters is seen as a perk as it is seen as the primary avenue to produce offspring. In a passage that details the life and death of characters (from disease to old age) the Dungeon Master’s Guide encourages the dungeon master to frame the character’s legacy in terms of offspring: “once a character dies due to old (venerable) age, then it is all over. If you make this clear, many participants will see the continuity of the family line as the way to achieve a sort of immortality.”19 The expectation of patriarchal lineage shows how Dungeons & Dragons assumes that players will design able-bodied, heteronormative characters. As McRuer argues, “the system of compulsory able-bodiedness that produces disability is thoroughly interwoven with the system of compulsory heterosexuality that produces queerness.”20 In this sense, there’s a strong push to reinforce the centrality of able-bodied and heteronormative characters within the play structure by excluding disabled and queer characters from representation.

In the words of Jaako Stenros and Tanja Sihvonen, Dungeons & Dragons “grew from… a particularly conservative youth culture.”21 As noted in their text “Out of the Dungeon,”—which addresses queerness in a wide array of role playing games—Stenros and Sihvonen highlight this statement from the Red Box (1983) Version of D&D:

In D&D games, as in real life, people have ethical and theological beliefs. All characters are assumed to have them, and they do not affect the game. They can be assumed, just as eating, resting and other activities are assumed, and should not become part of the game.22

In their analysis of the Red Box version of the Dungeon Master’s Guide, Stenros and Sihvonen argue that “we can assume that sexuality is covered by this statement: ‘it should not be part of the game.’23 This complicated denial of sexuality in general and aligning queerness with evilness echoes through the silence and stillness of some of the later D&D texts and questions what access a queer identity would have in the gamespace.

The updated third edition of the Dungeons & Dragons Players Handbook has even less to say about queerness than the 1979 version of the text. The only mentions of sex are in terms of physical height and weight. The entirety of the entry on gender is: “Gender: your character can be either male or female.”24 This recalcitrance to speak on sex and sexual orientation says little on its own merit, as it lacks the further contextualizing elements of morality that appeared in the original AD&D manual. This lack of representation has led to “allegations that … Dungeons & Dragons publisher TSR… had rules that banned the depiction of queers. Although such claims are common, we have thus far been unable to substantiate them.”25 It reinforces a gender binary while not advancing its previous links between sexuality and morality. There is a discussion on morality and a character’s so called “alignment” on the axes of good and evil or chaotic and lawful, but these valuations avoid language of desire.26 In terms of queer access to the realms of roleplaying, the updated third edition of Dungeons & Dragons neither works against previous anti-queer depictions, nor does it attempt to reify it. This silence seems to emphasize the removal of sexuality from Dungeons & Dragons that was prescribed in the Red Box edition.

Disabled Characters Tell Better Stories

Where the texts are silent on sexuality, they speak volumes about disabilities and their implementation. In terms of disability, the era of third edition Dungeons & Dragons and Pathfinder adds complexity and conflict to disabled characters in a manner that increases their visibility and representation. They encourage the use of disability in roleplaying, but degrade the idea of living as a disabled character. In the Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide (revised third edition), the section on NPCs offers advice on adding depth to characters played by the dungeon master. In this section it gives a table of “One Hundred Traits” random traits that make them more “interesting” and “memorable.”27 Of these ninety nine options, at least twenty five easily lend themselves to some form of physical or mental disability, such as “walks with a limp,” “visible wounds or sores,” and “neurotic.”28 The dungeon master is encouraged, then, to create NPCs with disabled traits in order to make them more memorable to the players. This use of disability as a storytelling element evokes the literary process of “narrative prosthesis” as constructed by David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder. In their work, Mitchell and Snyder find that disability is often used as “as a stock feature of characterization and… as an opportunistic metaphorical device.”29 They argue that while disabled characters are ubiquitous in literature, they are often only present to augment the story of an able bodied character, or to be exploited for the sake of the narrative and “cured,” “obliterated,” “rescued,” or “revalued.”30 This edition of the Dungeon Master’s Guide emphasizes that these traits “don’t have any effect on ability scores, skills, or game mechanics”31 which are used algebraically to determine successes in the realm of the game. Instead, these traits exist to be storytelling elements, small quirks that add depth to NPCs.

Pathfinder is a bridge between the updated third edition and fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons. For this reason,it offers unique insight into the accessibility of the gamespace. Its market-competitiveness with Dungeons & Dragons and its own claims to storytelling merit its inclusion in this essay. The Pathfinder GameMastery Guide offers some insight into the application of this literary process to roleplaying games at the cusp of where it transitions from advice regarding player characters to where it offers advice on the creation of NPCs. The guide emphasizes the crucial role of NPCs to the story and states “designing NPCs thus becomes an exercise of creativity, which the GM [game master] can cultivate by reading fantasy literature or watching fantasy on the screen.”32 The ties between NPCs and stock disabled characters becomes evident in this context, given that roleplaying storytelling draws heavily on established literature—visible as well in the original AD&D dungeon master’s guide when nudging dungeon masters to follow storytelling canon instead of trying to make their own, non-human oriented campaign: “how can such an effort rival one which borrows from the talents of genius and imaginative thinking which come to us from literature?”33 Here, one can see the perpetual intertextuality between literary process and roleplaying tendencies.

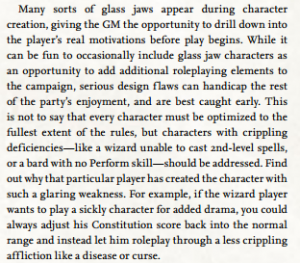

In the passages pertaining to handling player characters, the GameMastery Guide re-emphasizes the use of disability as a stock storytelling feature, but also adds caveats that it can be taken too far. In the section that gives advice to the game master on different types of characters and players, it warns: “While it can be fun to occasionally include glass jaw characters as an opportunity to add additional roleplaying elements to the campaign, serious design flaws can handicap the rest of the party’s enjoyment, and are best caught early. This is not to say that every character must be optimized to the fullest extent of the rules, but characters with crippling deficiencies… should be addressed.”34 The GameMastery Guide uses forms of the word cripple frequently to emphasize how playing a disabled character would not only be unenjoyable for the player of the character, but that “The game should not be made less enjoyable—and the party crippled—[for] a single character.”35 Even when this guide was published, its word choice seems distinctly anti-disability. As early as the year 1998, “cripple as a descriptor of disabled people [was] considered impolite.”36 The GameMastery Guide’s publication in 2010 falls distinctly beyond this shift in the language of disability. In Pathfinder, disability is reified as a storytelling element, but only to certain degrees and in certain contexts. It follows the assumption seen that the foremost desire of player characters is a non-disabled experience within the roleplaying world. This continued denigration of non-normative people precludes them from the potentialities and futures offered in roleplaying games.

The framework of the updated third edition of Dungeons & Dragons and Pathfinder character system demonstrates many of the issues with roleplaying game handbooks discussed in Elsa “Reimagining Disability in Role-Playing Games.” In this article, Sjunneson-Henry discusses how “it is psychologically important to feel as though you are a part of the universe in which your story is set.”37 In the article, Sjunneson-Henry discusses how in many RPGs “disabilities are at best neglected… and at worst used as a punchline for a bad joke.” The language of character creation used in these handbooks alienates disabled players by warning against characters whose disabilities move beyond simply being a story point.

The fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons marks the most recent incarnation of the rules and suggestions for roleplaying on a large scale, and within it one can read changes in its messages about disability and queerness. In the fifth edition Player’s Handbook, the tables which suggest height and weight are no longer broken down by male and female of each race.38 Beyond this move away from reifying gender and sex constructs, the handbook offers the following advice: “Think about how your character does or does not conform to the broader culture’s expectations of sex, gender, and sexual behavior…You don’t need to be confined to binary notions of sex and gender… You could also play a female character who presents herself as a man, a man who feels trapped in a female body, or a bearded female dwarf who hates being mistaken for a male.“39 These passages of advice not only move beyond previous edition’s concepts of sexual preference being linked to morals or being absent from consideration, but they also carry with them explicit suggestions and implied conversations. The implied conversation of this direction is that the player can discuss with the dungeon master what the prevailing constructs of sex and gender are in the realm of the game. This conversation hinges on strong awareness of how sex and gender are formulated as ideas and how they are performed within the realm of the roleplaying game. The suggestions for character creation here make an accessible route into the game for transpeople, nonbinary people, and queer people whose sexual and gender identity are fluid. This affirmation of identities moves past the previous assumptions of the game that queer identities were undesirable or outside of consideration for players and characters. In constructing a framework to discuss the multiple potential sexes and genders of a character, the absence of any nuanced suggestion for disability becomes suspect.

In the central text of character formation, the game continues much of its prior views and expectations of disabled characters, however there are indications in other areas that the narrative of disability in Dungeons & Dragons is changing. In the player character generation portion of the fifth edition Player’s Handbook, the entirety of its “other physical characteristics” section is: “You choose your character’s age and the color of his or her hair, eyes, and skin. To add a touch of distinctiveness, you might want to give your character an unusual or memorable physical characteristic such as a scar, a limp, or a tattoo.”40 Again, the idea of narrative prosthesis appears. However, in the entry for the suggested characteristics of the soldier class, the Players Handbook gives examples of personality traits which align with a possible mental disability. Among the traits of the soldier are listed possibilities such as “I’m haunted by memories of war. I can’t get the images out of my head,”41 “I sleep with my back to a wall or tree, with everything I own wrapped in a bundle in my arms,”42 and “I’ve lost too many friends, and I am slow to make new ones.”43These traits, while not explicit, evoke categories of re-experience, avoidance, and arousal trigger from the diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder44 (Black and Grant 178-80). By including these suggestions for players to consider and portray, Dungeons & Dragons fifth edition seems to be moving away from a flat portrayal of disability. This modeling of non-normative thought is a beginning towards placing peoples with different minds and bodies into the realm of the game. It begins to move towards access for those with mental or physical disability, without the explicit consideration given to queerness.

These alternate forms of entry into the gamespace make for an uncomfortable potentiality. In terms of representation incomplete incorporation may well be a step in the right direction, but representation alone lacks the nuance and open-endedness one expects of a game system that is founded upon open-ended stories and inventing one’s own story. In her work, “Race In/For Cyberspace: Identity Tourism and Racial Passing on the Internet,” Lisa Nakamura questions the cultural tourism of middle class white males in the online roleplaying MUD LambdaMOO. In the cyberspace of LambdaMOO, Nakamura finds that “the entire social space of LambdaMOO is ‘whited out’ in the name of cybersocial hygiene.”45 By this, she means that there is an overarching whiteness that attempts to quash non-stereotypical representations of Asianness. This structure exists to perpetuate cultural tourism on the part of the privileged majority of white males who interact with the gamespace. By opening theoretical access to gamespace in Dungeons & Dragons, the handbooks offer both the opportunity for non-normative players to position themselves in the game and the opportunity for non-disabled or non-queer players to “pass” as these characters.

In the spirit of Dungeons & Dragons it becomes necessary to push, then, to imagine an actualized roleplaying experience for disabled players and/or characters. As Nakamura concludes: “a diversification of the roles which get played, which are permitted to be played, can enable a thought provoking detachment of race from the body, and an accompanying questioning of the essentialness of race as a category.”46 Such a detachment becomes more complicated when addressing disability, where “social constructionism makes it possible to see disability as the effect of an environment hostile to some bodies and not to others, requiring advances in social justice rather than medicine.”47 In order to accommodate discussion on disability, Dungeons & Dragons would need to address and incorporate not only non-normative minds and bodies within its models for play, but a discussion of various ways that social systems disavow their presence in society. It would not be sufficient to only introduce a character that does not use their legs without also discussing why the world within the campaign does not accommodate this difference or why societies would treat the character differently than one who does use them.

As can be seen from the changing text of the sourcebooks, there are internal stresses with queerness and disability, where queerness receives explicit endorsement for consideration and only subtle hints are given for permissible, rounded disabled characters. This tension is not necessarily negative, but provides a suitable off-balance conceptual space to consider the futures of disabled identity in roleplaying games. This tension reflects alternate conversations that are occurring at a level separate from that of the handbooks. It also reflects the necessity of different strategies for including queer and disabled discourse in the game.

–

Featured image “IMG_7648” by Marc Majcher @Flickr CC BY-SA.

–

Michael Stokes is an independent scholar whose work focuses on the complicated interactions between disability and science fiction films and literature. He currently holds a BA in English from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Campus and an AA in Theatre Studies from Grand Rapids Community College. His writing centers on the entangled relationships between the representation of disabled characters in sf literature from the 1940s to present with race, queerness, and sexuality. In July of 2017, he will be presenting at the International Conference on Educational, Cultural, and Disability Studies. When not actively writing, he reads and watches science fiction between Dungeons & Dragons sessions and board game nights.

One thought on “Access to the Page: Queer and Disabled Characters in Dungeons & Dragons”

Comments are closed.