The Grizzled (2015) sits on my shelf, usually at the top of a stack of games in small boxes. Whenever we decide what game to play, its evocative cover art1 draws us towards it. The game’s tagline, visible on all four sides and the top of the box, asks “Can friendship be stronger than war?” Inevitably, someone picks it up, and inevitably, I warn them, “This game will make you have feelings. Usually despair and sadness.” This gives them pause, as these are not feelings that games usually evoke in us. Challenge, struggle, chagrin? All of these are common, especially in cooperative games, but The Grizzled is not most cooperative games.

The Grizzled is a fully cooperative card game by Fabien Riffaud and Juan Rodríguez, first published in France by Sweet Games, and republished in the United States by Cool Mini Or Not (now CMON Limited). While an expansion set, The Grizzled: At Your Orders, was published in 2016, this analysis will focus primarily on the base game. As I warned my fellow players, The Grizzled is notable because it encourages its players to feel things other than the joy, challenge, and pleasure people often seek from games. It sets itself apart from many cooperative games by insisting that injuries and traumas to one’s character are unavoidable, and by centering its core game mechanics on facing the effects of trauma, rather than attempting to escape or evade its causes. The Grizzled tackles a difficult subject, placing players into the shoes of French soldiers mired in the trenches of the First World War. It does not make light of its theme. The game’s insistence that players identify with their characters, its handling of injury and trauma to players’ in-game representations, and its willingness to abstract the tactical considerations of war while dealing with its human effects all combine to create a game that sets itself apart from both wargames and cooperative games in terms of its degree of affective gameplay.

Gameplay Overview

In The Grizzled, each player takes on the role of a French soldier in the trenches of WWI. Players play cards from their hands, attempting to deplete one draw deck (the Trials deck) before a second draw deck (the Morale Reserve) is depleted. Most of the cards in these decks are “Threats.” When played into a central tableau, these cards represent the dangers that characters encounter on their missions. Snow, shelling, rain, gas masks, nightfall, and “the whistle” (the signal to begin an attack) are represented in varying combinations on the Threat cards. The game proceeds as a series of “missions,” in which players attempt to play as many Threat cards as they can, one card per player per turn. If three of the same symbol are visible in the tableau, the mission fails, and all the cards in the tableau are shuffled back into the Trials deck, delaying victory. If all players “withdraw” before the failure condition is met, the cards from the tableau are discarded.2 Shuffled in with the Threat cards in both decks are “Hard Knocks” cards. Instead of being played to the central tableau, players attach these Hard Knocks to their character cards. While the Threats come and go with each mission, the Hard Knocks are persistent, remaining attached to a single player-character until the group is able to remove them (see below). 20 of the game’s 59 cards are Hard Knocks (the remaining 39 are Threats), so players have a good chance of having both Threats and Hard Knocks in hand.

The central tension of each player’s turn consists of deciding whether to play a Threat card, which has a lesser impact, but impacts the group as a whole, or a Hard Knocks card, which has a greater impact on that player only. This sort of tension is common in cooperative board games, as players seek to mitigate the unavoidable negative consequences generated by the game’s systems while simultaneously focusing on advancing another goal that leads to their victory. What makes The Grizzled unique among cooperative board games is that the unavoidable consequences accrue directly to the players’ characters. By contrast, in Pandemic (2008), the unavoidable consequences impact the board state, not the characters. Diseases erupt around the board, forcing players to react and change their plans, but characters in a city during an outbreak, for example, are not infected with the disease. In cooperative games like Forbidden Island (2010) and Forbidden Desert (2013), players’ characters can suffer consequences (death by drowning or thirst, respectively), but such outcomes are not unavoidable — indeed, if any character in either Forbidden game dies, the game ends in an immediate loss. A game like Reiner Knizia’s The Lord of the Rings: The Board Game (2001) is closer to The Grizzled, in that, unlike the games described above, both have unavoidable negative consequences that accrue directly to players’ in-game representations of themselves. In The Lord of the Rings, hobbits (players’ characters) suffer the deleterious effects of carrying the Ring and confronting enemies. This causes them to move towards Sauron’s marker, and their eventual elimination from the game, on a “corruption track.” In both games, instead of seeking to protect their in-game representations from all harm, players work to distribute the harm across multiple player-characters in a way that makes achieving the win condition possible. The difference is that moving on the corruption track (in The Lord of the Rings) does not impede players’ in-game actions, whereas accruing Hard Knocks (in The Grizzled) imposes limiting conditions on the character. These limiting conditions therefore shift the player focus toward the effect of trauma, rather than its cause, a point which will be explored further below.

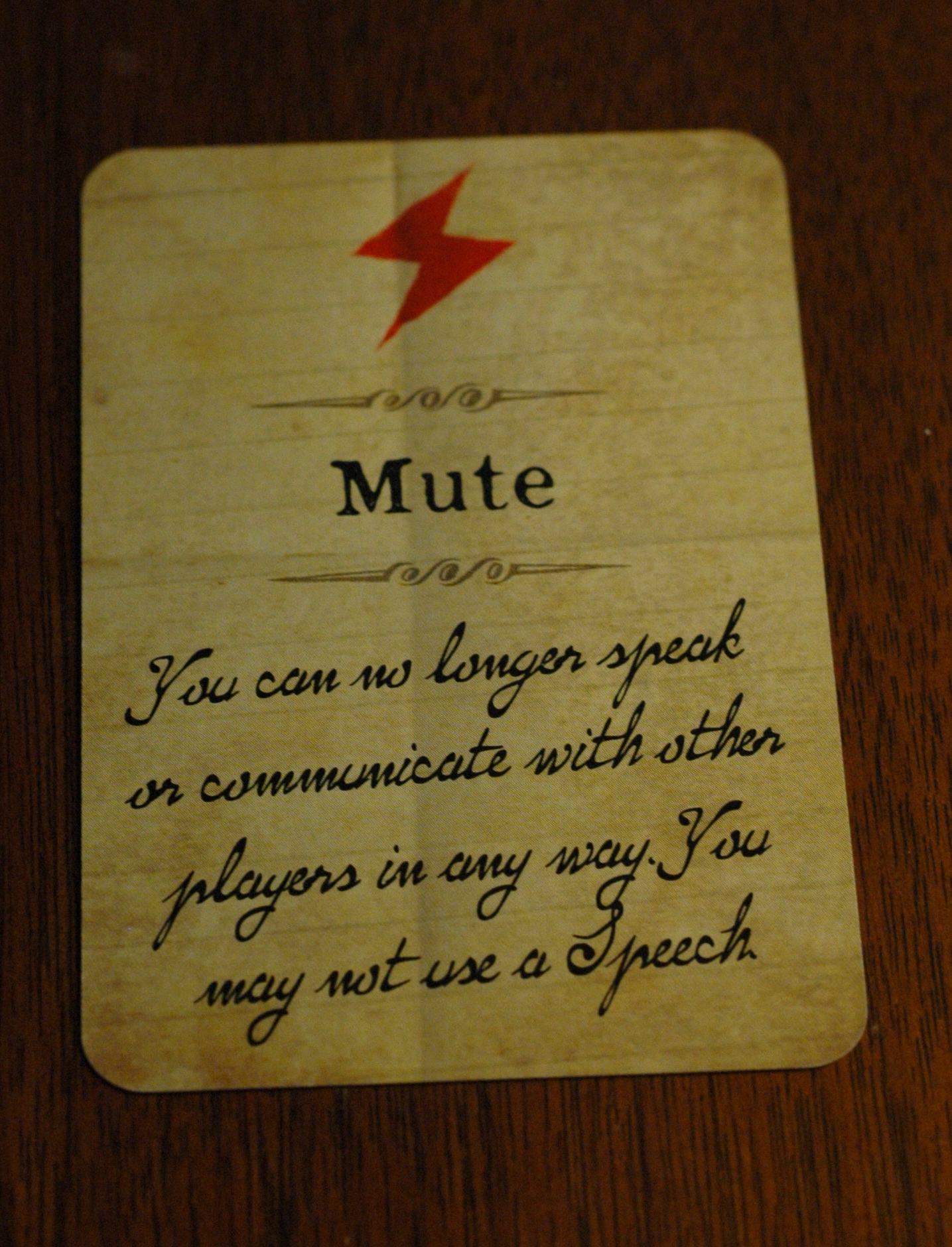

Consider the text of one of the Hard Knocks cards: “Mute: You can no longer speak or communicate with other players in any way. You may not use a Speech.” Having played this Hard Knock on herself, a player removes her voice from the collaborative gameplay. Other Hard Knocks force players to interact with Threats differently, limit choices they can make when entering the game’s interstitial phase, or place more cards onto the deck that stands between players and their victory.

Identification

The Mute card suggests an important detour from a further mechanical investigation of how The Grizzled handles injury and trauma to players’ characters. The Grizzled’s insistence that players identify with their in-game representation is epitomized in this card’s effect. A Hard Knock like “Clumsy” (which forces a player to draw and play a random Trial for the group to deal with, increasing their collective chances of failing the mission) represents the trauma in the abstract, by tying it to a game mechanic. The newly-clumsy character is understood to have encountered a diegetic obstacle, such as stumbling into barbed wire or falling in the snow. “Mute,” however, creates both diegetic and extra-diegetic consequences by forcing the player to embody the effect of the trauma. The character is mute, and so is the player.

The Grizzled encourages this type of identification with one’s character in its rulebook, as well as in its gameplay. The introduction states: “The Grizzled offers each player the chance to feel some of the difficulties suffered by the soldier in the trenches.”3 Additionally, this section invites players to connect their in-game characters to real-world events, noting that “some of the characters in this game were real people.”4 The rulebook includes recreations of actual letters from French soldiers as graphical elements interspersed throughout the rulebook. These are extra-diegetic cues; that is, the rulebook text is not part of “playing the game,” strictly defined. Nonetheless, the game’s rules tell us how to play the game, both in terms of their content and their form. Rather than suggesting that these cues encourage the players to identify themselves with real-world French WWI soldiers, I believe that this move on the game’s part serves to strengthen players’ identification of their in-game representation with themselves. The reality of the French soldiers, their presence as figures outside of the game, connects to the players, who are also figures outside of the game. By bringing real, historical personas into the game’s magic circle, The Grizzled collapses the inside-the-game/outside-the-game dichotomy, strengthening players’ identification with their characters.

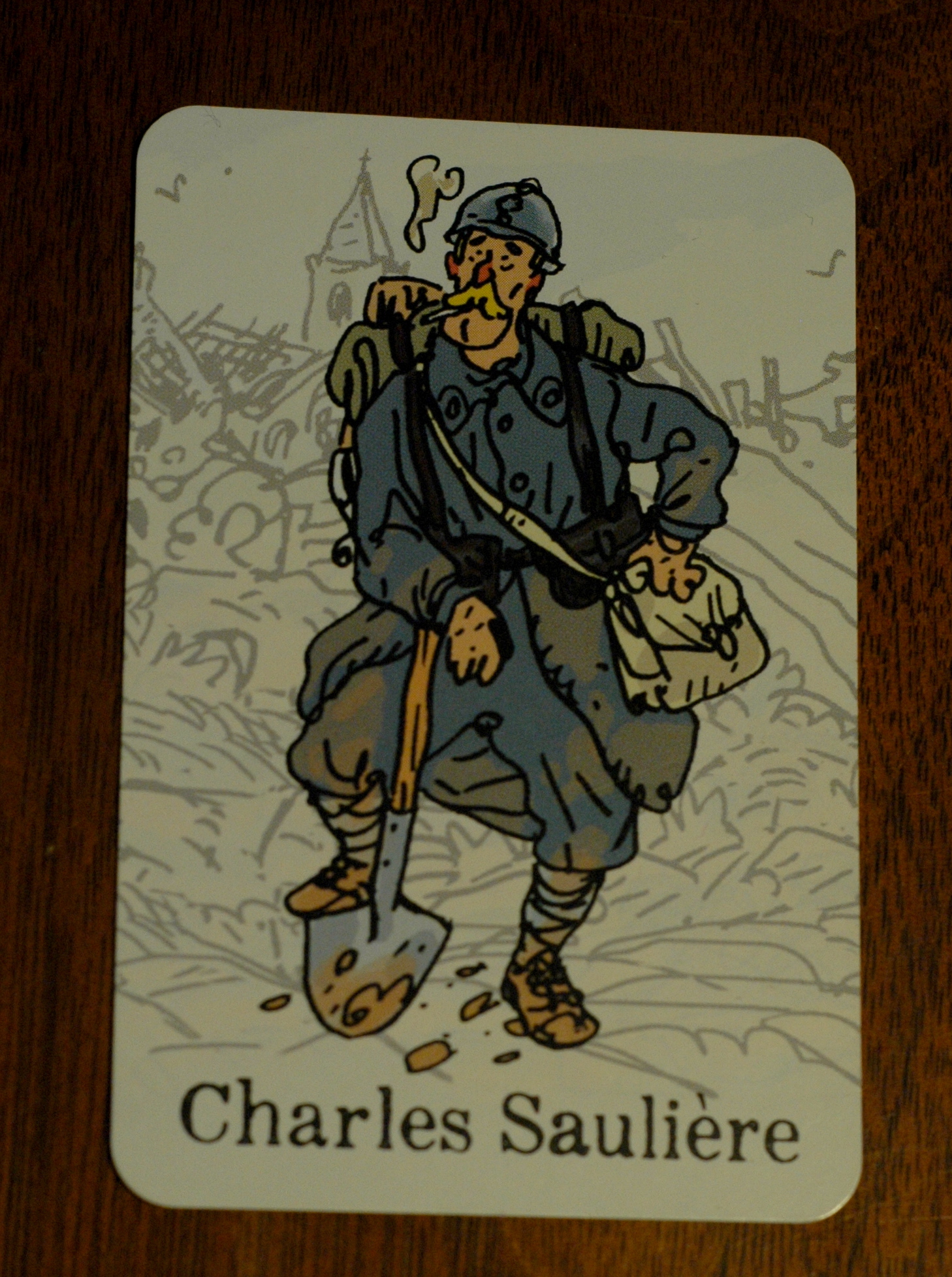

The in-game site of this identification is the player’s character card (in the recent expansion pack, these are replaced by cardboard standees). These six cards each have the image of one of the “grizzled”:5 white men of varying heights, builds, and facial hair in military uniform. As an able-bodied white man, these images are easy sites of identification for me. However, it is important to acknowledge that not everyone will find these sites of identification so simple. Antonnet Johnson’s essay “Positionality and Performance”6 serves as a reminder that players may not always choose to follow the game’s hegemonic suggestions regarding how they identify themselves within a game. Playing The Grizzled subversively (perhaps by refusing to follow its cues for identification in resistance to its overwhelming whiteness and maleness) may unlock other ways in which this game further expands the range of games as a whole, or it may expose the game’s inherent biases. For the purposes of this analysis, however, the fact that the game suggests that players identify with soldiers in the trenches is itself a subversive move. By placing players into the shoes of “ a group of inseparable friends” in “the village square,” the game engages in subtle but effective class criticism. Instead of playing as generals and field marshals causing impersonal military units to accrue damage counters, The Grizzled asks players to play as lowly soldier Charles Sauliére, who will accrue Hard Knocks like “Fearful,” “Fragile,” and “Panicked.”

Mechanical Representations of Trauma

In many cooperative games, the negative consequence is often a trauma or injury to the player’s in-game representation, and in many of these games, the focus (both mechanically and narratively) is on the way that this trauma occurs. The Grizzled upholds the first, but, as we have seen, inverts the second. In The Grizzled, the focus of injury to the player’s character is on its effect. This difference is at the core of what sets The Grizzled apart from other cooperative games.

The Hard Knocks cards have already been discussed: Players play cards from their hands that attach to their character, giving their character a limiting condition that represents the effect of that character’s experience in the mission. As characters receive multiple Hard Knocks, the synergies between these cards force the players as a group to adjust and adapt their gameplay. Some cooperative games share this sort of gameplay: In Forbidden Desert, player-characters start with full water, and, as the game goes on, consume their water. If any character runs out of water, that character dies, and the game ends in a loss. While construing drinking water as injury or trauma is a stretch in terms of meaning, the game’s mechanics encourage players to think of it as such. Thus, group gameplay in Forbidden Desert changes in reaction to individual characters’ water levels, as characters can carry and distribute water, bringing some characters back from the brink of death, but at the expense of making progress towards the game’s other goals.

The Grizzled has an analogous game structure: Giving support. As each player leaves the “mission” phase of the game, they secretly set down a support tile. These tiles have an image of a cup of coffee on one side, and an arrow (superimposed over a soldier drinking the coffee) pointing left, right, two places left, or two places right. After the mission ends, players reveal these arrows. Whichever player has the most arrows pointing at them (whichever character received the most care, as symbolized by cups of coffee, from his comrades) may discard two Hard Knocks cards. Importantly, if there is a tie in support, no player receives the benefit.

While the narrative core of the game (especially in the “At Your Orders” expansion) is in the mission phase, this phase is structurally simple: In a sort of negative spin on the classic set-collection mechanic,7 if the tableau contains three or more of any “threat” symbol, the mission fails. The support phase, which occurs between the missions, is more complex. It is simple to count threat symbols and decide which should not be played. It is more complicated to assess whether “Clumsy” or “Mute” is a bigger problem for the group, and even more complicated to decide how to point the arrow on your support tile when you are prohibited from communicating about this during the mission. Maybe your group of players has decided that one player’s Hard Knocks need to be dealt with at the start of the mission. Then, as the mission progresses, another player plays more dire Hard Knocks onto their character. Do you change your support assignment, hoping that your fellow players will follow your lead, or do you stick to the plan, hoping that the new Hard Knocks can be dealt with in future rounds? If the “mission” phase is like a negative-outcome set-collection game, then the “support” phase is like a social deduction game8 where, instead of trying to conceal your intentions, you are trying to get (or keep) the group on track, while being expressly prohibited from communicating.

The support mechanic creates a dynamic described by David Phelps and his co-authors as “an in-game dilemma of two competing goods, one of which we must sacrifice (at a costly loss) to the other.”9 Phelps, et. al. describe games that are neither fully cooperative nor fully competitive as embodying this tension, yet The Grizzled, a fully cooperative game, also contains moments of tension and sacrifice. While all players are working together toward the same goal, the game’s limits on communication, the limiting impacts of the Hard Knocks cards, and the players’ strong identification with their in-game representations all lend depth and tension to such sacrifices. By preventing players from communicating about where support is being directed, the game’s rules force a semi-cooperative state where players all acting in the best interests of the group can create an outcome that is detrimental to the group.

There are (many) moments in The Grizzled when defeat seems inevitable, or when the choice is between two options that seem equally bad. In “The Allure of Struggle and Failure in Cooperative Games,” Douglas Maynard and Joanna Herron eloquently describe these moments in other cooperative games.10 While much of their work focuses on in-game communication, which, in The Grizzled, is severely limited, one of their conclusions describes the experience of playing The Grizzled to a tee: “When experienced together, both the process of losing and loss as a final result carry with them opportunities for camaraderie, humor, memory-making, and storytelling. In addition, the collaborative nature of the activity reduces the sting of failure through a shifting of focus from the self to the group.”

Whether winning or (more often than not) losing, players in The Grizzled must engage with sacrificing for the better of the group and dealing play-limiting Hard Knocks to themselves. While I have not done the sort of extensive and documented experiential playing that Maynard and Herron use to reach conclusions about their plays of other cooperative games, I have played The Grizzled often enough to generalize about losing it: It always feels like a trial suffered through together. While my playing groups have not focused on humor as a reaction to The Grizzled, the “camaraderie… memory-making, and storytelling” that Maynard and Herron describe characterize this game’s outcome, regardless of winning or losing.

War & Abstraction

In “Orientalism and Abstraction in Eurogames,” Will Robinson highlights the tendency of European-designed games to abstract violence; that is, to hide their violence in obtuse mechanisms, or to entirely ignore violence that was historically present in the era that the game represents.11 In writing about GMT’s COIN series of wargames,12 Cole Wehrle says: “Though all wargames concern violence, many find ways of burying the gruesome details of war… Wargames are not so much about war as they are about a specific part of war.”13 The Grizzled, while burying some of the gruesome physical details of war, faces the psychological traumas of war head-on. The game abstracts the causes of those traumas in order to focus on their effects. Narratively, of course, it is understood that the players’ characters receive these Hard Knocks because they are soldiers in WWI. The game, however, does not have a mechanic for players to decide to enlist, join the French army, march to the front, or even make any warlike tactical decisions, aside from “Should I remain in the mission, or should I withdraw?”

The Grizzled abstracts those elements that so many wargames foreground, while not abstracting war entirely. The abstraction of violence is common in strategy games, and in Eurogames in particular. Players in Catan (1995) and Ticket to Ride (2008) never choose to fight, roll dice to resolve combat, or move troops. Nor do players in The Grizzled. Additionally, like a wargame, The Grizzled delivers a thematic experience set in the midst of combat. What The Grizzled does differently than many wargames, however, is to focus on the effects of war and violence, rather than on the procedural concerns (supply lines, troop positions, weapons ranges). Rather than ignoring the harsh impact of war upon humanity, The Grizzled tackles it head-on. What is remarkable about this feat is not that it is accomplished skillfully. Games can tackle many difficult subjects with care. What is truly remarkable is that The Grizzled manages this pointed critique while also creating a fun, playable game experience.

Conclusion

After playing The Grizzled, the game seems to hope that you have felt something. The rules introduction text ends with this injunction: “The path to victory may seem difficult, but don’t get discouraged – persist and survive the Great War!”14 By highlighting discouragement and persistence, the rules are focused on the game’s effect on its players’ emotional states. This focus is not unique among all games, but The Grizzled is unique in how well it achieves the monumental task it sets for itself. The game’s insistence on player identification with their character, coupled with its focus on the effects (rather than the causes) of trauma, set this game apart from both wargames (where it has thematic resonance) and cooperative games (where it has formal resonance). The unique feeling of playing The Grizzled is heightened by its willingness to tackle an uncomfortable topic. While games that celebrate, abstract, or painstakingly re-create violence and wars are common, games that critically reflect on a particular war or the concept of violence in general are rare. Yet The Grizzled does just that. From its tagline (“Can friendship be stronger than war?”) to its immersive gameplay, wherein characters must care for their psychologically damaged comrades, The Grizzled seems committed to a stance that is, if not anti-war, at least critical of war’s impact on the individuals most caught up in it. To play The Grizzled is to enact, and (if you draw the “Mute” card) embody this critique. Such messaging could become didactic, if it were not nestled into effective systems of identification (with one’s character) and representation (of the devastating effects of injury and trauma). By creating a game that plays well, The Grizzled’s designers have created an effective vector for their criticism of war.

Such social awareness must be the future for board games if the form is to move beyond the realm of the mere commercial, and game designers whose work overlaps with the worlds of academia and performance art are beginning this movement.15 The Grizzled is undoubtedly a game with a social message, yet it is also a game that has found commercial16 and critical17 success. Such reception of a game that is so uniquely focused on a message that is, in modern, militaristic culture, unpopular, is encouraging, both to those invested in ending war, and to those invested in creating innovative and socially-conscious games.

—

Featured image “French soldiers, likely after receiving the Military Medal for acts of bravery – Somme, France 1916.” CC BY-NC-ND by Taylor S-K on Flickr.

—

Greg Loring-Albright makes and writes about tabletop and real-world immersive games at gregisonthego.wordpress.com

Great analysis, thank you!