Settlers of Catan is a German board game by Klaus Teuber, first published in 1995. The game pits players against one another in an economic civilization-building race as they build structures and gather resources on the hexagonal tiles that compose the game’s board. The game has achieved critical acclaim (winning the Spiel des Jahres in the year of its release) and popular success, especially in the U.S.: a 2010 Washington Post piece called it “the game of our time.”1 Board Game Geek, a popular international board-game hobbyist website, ranks Settlers of Catan 168th out of 79,923 games (as of 8 October, 2015) on its “hotlist.” This paper situates Settlers of Catan in its context as a popular game in the U.S., and proposes a subversive gameplay modification that addresses that context.

It was during a game of Settlers of Catan that I began to wonder why, or even if, Catan was uninhabited.2 I played on, though not without pushing down even more pointed questions about the narrative that I, as a settler of Catan, was enacting. Whose wheat was I harvesting when I rolled a six? Whose land was I altering when I built my roads and settlements? And with what entity was I trading when I shipped two wood in exchange for one resource of my choice at the port?

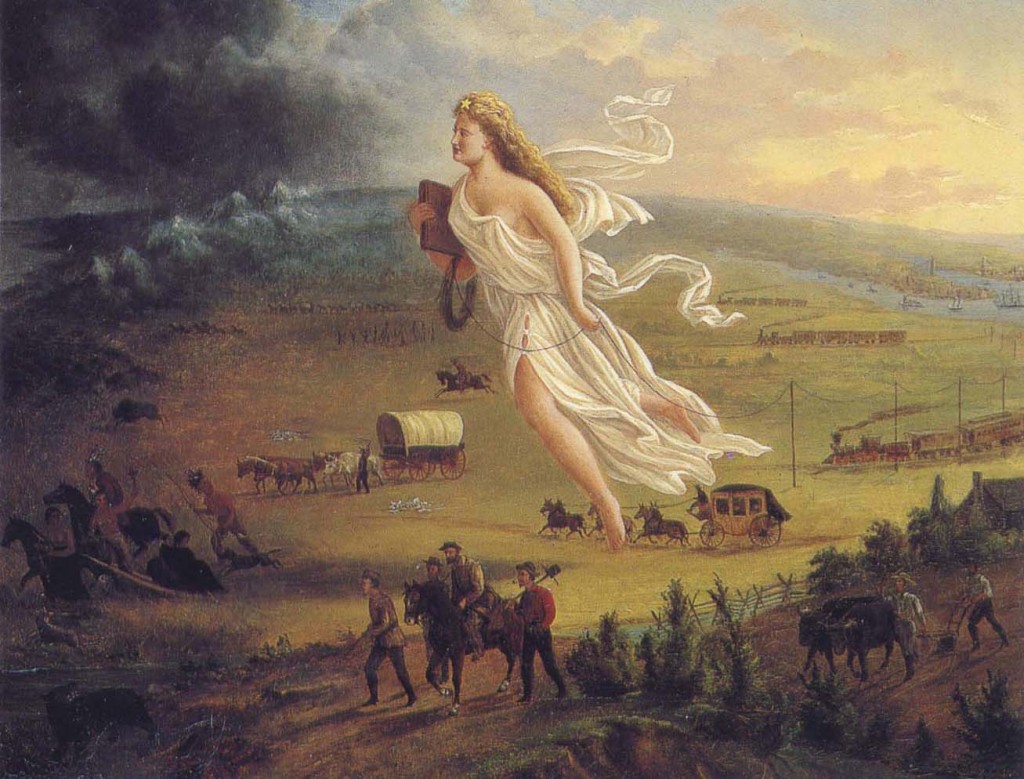

It became clear, at least to me, a white person playing this game in the U.S. in the early 2010s, that every game of Settlers of Catan re-tells the American myth of White European settlers stumbling upon a fertile land that was theirs by right, encountering no meaningful resistance, and acting on behalf of God and Country to develop economies, settlements, and cities in this “New World.” My first thought was to never play Settlers of Catan again. But this response seemed inadequate: while it might solve the problem for me, it would not equip anyone else to wrestle with these troubling issues, and would put me in some awkward positions whenever Settlers of Catan came up as a possible game to play. So I decided to come up with a new game, based on Settlers of Catan, but one that would bring to light the things that had so troubled me about the game.

Settlers of Catan, both by its title and its thematic elements, situates itself as a game about settling new land. While the game does not root itself in any historical reality, playing it in the U.S. creates a link to the real historical settlement and concurrent genocide of indigenous peoples. Consider the “frontier myth,” a phrase that describes the work of Frederick Turner Jackson, whose 1893 essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” attributes the rapid development of the U.S. in the late 19th century, and the specificity of the U.S. American character, to mystical forces contained in the “empty” and thus edenic American West.3 Settlers of Catan, by allowing its settlers to find the island of Catan in a similarly edenic state, reifies this myth, which helped to render American Indians invisible. Thus, Settlers of Catan, when played in the U.S., is complicit in continuing to make indigenous communities invisible. Primarily in order to counter this troubling aspect of Settlers of Catan, and to create a game that I feel comfortable playing, I have designed a variant of Settlers of Catan titled First Nations of Catan.

First Nations of Catan: Introduction and Summary

In First Nations of Catan, one player (of the possible four that a standard Settlers of Catan set allows) plays as the First Nations, the indigenous inhabitants of Catan.4 These semi-nomadic people have the same goals as the Settlers (earn 10 victory points by building settlements, cities, and buying development cards), though they accomplish them in different ways.

Rather than playing on the edges and corner of the game’s hexagonal tiles, as the Settlers do, the First Nations inhabit the center of each tile, signaling their centrality to and initial presence on the island. This creates visual contrast with the Settlers, who cannot penetrate the interior of any hex tile, but instead are limited to building their roads along the edges of the tiles and their settlements at intersections of roads. The island of Catan is open to its indigenous people occupying its hinterlands, but forces the invading Settlers into the liminal spaces. This parallels the historical realities of the (White) settlement of North America in relation to indigenous North Americans: European settlers moved inward from the coasts, and later, along major rivers, while indigenous peoples as a whole occupied the interior in addition to the coastal lands.

While this rule creates an attractive metaphor, it limits the First Nations player’s opportunities: In Settlers of Catan, players may gather a resource from any one of the three hexes that their settlement abuts. By forcing the First Nations player into the center, First Nations of Catan significantly reduces their resource-gathering capabilities. This metaphor runs contrary to the realities of North American settlement: indigenous peoples were successfully planting, harvesting, and hunting on the land while European settlers were struggling to adapt to unfamiliar plants, soils, and weather conditions. Nonetheless, I wanted to create a game where the visual representation of the First Nations differed from that of the Settlers on the playing space, and having the First Nations play in the center of the tiles accomplishes this.

To restore balance of resource opportunities to the game, I have given the First Nations player another playing piece: The Tribe. This marker can move across the board, gathering resources as it goes. The Settler players have no such game piece at their disposal. The Tribe piece also allows the First Nations player to take military action against the Settler players, who may only defend themselves, and may not initiate military action. This is the most radical change that I have made to Settlers of Catan. In “Orientalism and Abstraction in Eurogames,”5 William Robinson suggests that, by focusing on economic development, Eurogames abstract and erase military conflict from the histories they represent, particularly military conflict against non-Europeans. By bringing military conflict from the realm of the abstract back into the realm of the explicit, First Nations of Catan undoes the disappearing act that Settlers of Catan performed on Catan’s indigenous peoples.

I realize that introducing a combat mechanic is troubling in its own right; games too often revert to simulated violent conflict as a thematic element. In my experience, many players enjoy Settlers of Catan precisely because it does not have a combat mechanic. However, this reading of Settlers of Catan ignores the presence and function of Knights and the Largest Army tile.6Just because the violence on Catan is not simulated by die rolling does not mean that it is not present in the game’s thematic materials. The empty, edenic state of the “frontier myth” is complicated and, to a certain extent, undone, as soon as violence occurs on the frontier. By creating a chance for more-explicit simulated violence to occur, I hope to have created a Catan that cannot be perceived as either empty or edenic.

Designer’s Diary

In this section, I will describe my process of designing First Nations of Catan. By leaving a trail, I hope that other designers will be encouraged to craft similar subversive games, and that new games will arise to fill the gaps that First Nations of Catan has left open.

The act of re-purposing a game’s pieces to create a new narrative counter to the original game’s narrative is not a new one. In “Strategies for Publishing Transformative Board Games,”7 William Emigh suggests and catalogues numerous instances of this practice. The ability of the player to usurp the role of the game-maker was, for me, perhaps the most exciting aspect of making First Nations of Catan, and the one that points to other ways for players of Eurogames to address some of these games’ failings. Having finished (as much as any game is every finished) First Nations of Catan, I can say that the game seeks to address the invisibility of indigenous peoples in the original Settlers of Catan, and to bring more explicit conflict to the economic-conflict-only ethos of Eurogames in general and Settlers of Catan in particular. Earlier drafts of this game addressed these issues in certain ways, but either did not address them fully enough, or raised too many other issues in the process. Additionally, I was looking to create a game that used the same pieces contained in a standard Settlers of Catan set, allowing anyone who can play that game to also play this new, revised version.

The game’s initial form did away with Settlers altogether, allowing players to play as various indigenous Catan-ians attempting to cooperate or compete with each other to develop society on Catan. While this solved the invisibility issue by foregrounding the existence of indigenous peoples on Catan, it quickly became apparent that this game was merely Settlers of Catan by another name, as the 2-4 factions looked and played almost identically to the Settlers in the original game.

The necessity to make explicit the abstract nature of military conflict in Eurogames was the solution I settled upon for the next iteration of the game. The historical narrative of the (European) settlers creating economic prosperity for their own competing factions by, as a group, disenfranchising the indigenous (American Indian) people needed to become more explicit in the gameplay. Needing both First Nations players and Settlers on the board quickly led me to the idea of asymmetrical gameplay: all the players are playing the same game, but may have different victory conditions, or have different ways of achieving the same victory condition. In short, the First Nations player needed different rules from the other players.

This iteration of First Nations of Catan centered on conflict. The First Nations would attempt to drive off the settlers while the Settlers attempted to eradicate the First Nations. As soon as I began this iteration, it became clear that it was more troubling than Settlers of Catan. Every player was aggressively enacting violence on another racial group, and had no other viable way to win. I hesitated here. Troubling games have their place, and can be very effective in reminding privileged White U.S. Americans (men in particular) of their own complicity in historical horrors. Consider Brenda Romero’s 2009 game Train, in which players must load a train with passengers.8 Only later do they learn that this train is headed to a Nazi concentration camp. Making such a game out of Settlers of Catan would, no doubt, be useful in a U.S. context, reminding those of us descended from European settlers that our wealth is derived from ill-gotten plunder and genocide. My project, however, was to create a Catan game that I would feel comfortable playing, and this troubling variant was not it.

I had, however, landed on a useful mechanic, and one that helped differentiate my nascent game from Settlers of Catan: hidden movement. Hidden movement games allow a player or players to indicate their position(s) not on the board itself, but in another way that keeps the position(s) of their pieces a secret, often by using pen and paper and a location-based notation system. In this too-conflict-driven version of First Nations of Catan, the First Nations player controlled the nomadic First Nations group as it roamed across Catan. The location of this group was noted by creating a map of the playing area on a piece of paper and marking the location of the group as a turn-based number inside the hex where it was currently (unbeknownst to the Settlers) located.

This hidden movement idea moved the game into its third iteration. The First Nations still had a secretly-moving group associated with them, but now their goal was not militaristic. Instead, all players were competing for points via the standard economic competition model of Settlers of Catan. The First Nations gained the ability to build settlements and cities, and gather resources as they developed their society alongside the encroaching settlers. A military option was available (the hidden piece could strike at Settlers, removing their constructions from the board) though it was not the only path to victory. This version of the game came close enough to accomplishing my goals, and was balanced enough when played, that I published it on my blog, along with a short rumination that became the core of this piece.9

This version, however, had two flaws—one practical, one ideological: By requiring players to use a pen and paper, and to draw a new map of Catan for every game, I had made the game harder to use, and thus less likely to be played. Additionally, if the invisibility of indigenous peoples was the concern I was hoping to address, using hidden movement seemed antithetical to my purpose, as it erases pieces from the play area.

By removing the hidden movement mechanic from the game (the Tribe piece replaces it) and retaining the other elements from the game’s third iteration, I had a game that worked both practically and ideologically. It required only one extra piece to be added to the basic Settlers of Catan game, and it played well. This is the game I settled on, and whose rules are included here.

First Nations of Catan: A Success?

Designing this game required balancing three directives: Create a game that was fun to play, that did not erase indigenous people from its narrative, and that did not deviate from the pieces contained in the basic Settlers of Catan game.

The first element is perhaps the easiest to confirm, as it was my primary concern when beginning this design. First Nations of Catan creates a narrative for Catan wherein indigenous peoples exist, interact with settlers, and have a fair chance of surviving the encounter by winning the game.

Based on limited playtesting, I believe I have accomplished the second goal as well. First Nations of Catan is a balanced, asymmetrical strategy game, in which classic Eurogame elements (economic competition, long-term planning) mesh with so-called “Ameritrash” combat simulation mechanics (dice-based combat, strategic positioning of military units).10 Each player has a fair chance at winning the game.

The final element was not, in fact, successfully met, but it was a compromise I was willing to make. By requiring an extra playing piece, I have added a small barrier to entry. I was hoping that players of First Nations of Catan would be able to simply download and print the rules, open their Settlers of Catan box, and play the game. But the Tribe piece requires one extra step: finding a piece from outside of the original game that will fit on the game board and be recognizable to all players. However, this is only a small hurdle, particularly for players who own any other board games, as almost any piece will suffice. Additionally, requiring the First Nations player to bring something onto the game board undoes, in a small way, the erasure of indigenous narratives that Settlers of Catan enacts.

First Nations of Catan accomplishes the goals I set for it, but there are many other possibilities for the island of Catan. Perhaps the troublingly violent variant that I had landed on could be expanded upon to create an uncomfortable reminder of European genocide of American Indians. Perhaps a cooperative game could be created to allow for a utopian Catan where Settlers and First Nations learn to co-exist peacefully.

In making this game, I set out to deal with my own discomfort at seeing problematic and inaccurate history recreated in a fictional realm. This type of re-writing is commonplace in reaction to non-game fictional texts. Fanfic and fan movies, for example, are well-established genres as reactions to movies, novels, television, and even video games. First Nations of Catan made me realize the possibility of game remixing as a sort of analog-game-based fan fiction. By using (mostly) the materials provided by the original text and remixing them, First Nations of Catan allowed me, as a player of Settlers of Catan, to address that which I find problematic about the original game without rejecting its system outright.

I am hopeful that players of Settlers of Catan will play First Nations of Catan and think about the differences between the games’ narratives, especially European-descended people playing in the U.S. However, the possibilities of game remixing more generally are most exciting to me, and I hope that by contributing to this stream, First Nations of Catan inspires other game-players to become game-makers and re-makers.

–

Featured image by Valentin Gorbunov CC BY.

–

Greg Loring-Albright makes tabletop and real-world immersive games as Plain Sight Game Co. (http://www.plainsightgameco.

–

Appendix: Rules for First Nations of Catan

When the Settlers arrive on Catan, they quickly encounter the First Nations of Catan, a semi-nomadic people who begin competing with them for the resources that, until the Settlers’ arrival, had been their undisputed right…

- First Nations of Catan

These rules allow one player in Settlers of Catan to play as the First Nations of Catan. Thus, this game supports up to 4 players (1, 2, or 3 Settler players and 1 First Nations player). This game has not been tested with the 5-6 player expansion set.

Use the basic Settlers of Catan game set, plus one playing piece in the color chosen by the First Nations player (see section B).

The following instructions address the First Nations player. Only a few changes affect the Settler players. These changes can be found in sections B, D, and E.

A. Setup

You place your settlement first, in the CENTER of any 1 tile. For the duration of the game, you will be playing on the center of the tiles, not on the edges as Settler players do.

The Settler player to your left starts the usual settlement placing process, with this modification: All Settler-player settlements must be adjacent to a tile that borders the water. This represents the Settlers’ arrival on Catan, while you have had the island to yourself since time immemorial.

Settler players place their first and second settlements as the basic rules describe. You place your second settlement after all Settler players have placed their settlements, again in the middle of any tile. This is the only time you may build on a tile that has Settler objects on its edges. See section E.

Once all settlements are on the board, find a marker in your color to indicate the Tribe. (Roads will be used for another purpose later. A City on its side will do in a pinch, or a ship or knight token from “Seafarers” or “Cities & Knights”, or any colored object that will fit on a tile). Place the Tribe at either of your settlements.

B. On Your Turn: Moving the Tribe

In addition to settling villages and building cities, the First Nations of Catan are nomadic, traveling to gather the resources they require.

On your turn, roll the die. You, and all other players, gather resources on the number rolled. Then, move the Tribe (see below), and finally, build or trade (if you wish).

You must move the Tribe every turn following this formula: Number on the dice / 4, rounded down. Thus, on a dice roll of 1-3, the tribe cannot move. On 4-7, they move one. On 8-11, they move two. On 12, they move three. The Tribe MUST move the full number of allowed movements. It may double-back over a tile multiple times, but it may not end on the tile where it started unless 1-3 was rolled.

The Tribe takes one resource card for every tile it moves through or lands on, not counting the tile where it began. If the Tribe does not move, it gathers the resource where it remains.

The Tribe does not move or gather resources on other players’ turns.

You may only build on the tile where the Tribe ends up (see section E).

Settler-players may NOT build on any side or corner of the tile that the Tribe occupies.

C. On Your Turn: Combat

Distressed at the rapidity of the Settlers’ incursions, the First Nations rally their forces and attempt to drive these invaders out by force.

After you have moved the Tribe, you may attack the Settler-player pieces adjacent to the tile where the Tribe ends its movement. Whenever you attack, you must attack ALL pieces adjacent to that tile.

Discard the cost of a Development card (sheep, wheat, stone). For each Settler-player’s piece (road, settlement, or city), roll a single die. If you roll 4-6, you destroy that piece. Remove it from the board and return it to the appropriate player. If you roll 1-3, you may not remove that piece this turn.

A Settler-player may play a Knight card AFTER you have declared your attack, BEFORE you roll, in order to defend any piece. That player should indicate which piece, if there are multiple, that they are defending. A Knight may defend a Settler-player piece of ANY color. If a Knight is defending a piece, you must roll a 6 to remove it. You may play your own Knight to neutralize a Settler-player’s Knight. Both Knights cancel one another out, but still count toward each player’s total number of Knights for the Largest Army tile.

If you successfully remove ALL Settler-player pieces from the tile where the Tribe is (or if there were none there to begin with), you may build there. If you successfully remove 2 or more Settler-player pieces, you have defended your territory! Place a road piece in your color on the center of the tile. This is not a road, but a Defended Territory marker. It is worth 1 VP at the end of the game.

Whenever a Settler-player builds on a tile that has a defended territory marker, remove that marker. If you reclaim that tile by defending territory at a later time, replace the marker.

Destroying only 1 Settler-player piece does not earn you a Defended Territory marker, though it will allow you to build on that tile.

D. On Your Turn: Building & Trading

You may, on your turn, build settlements or cities, or buy development cards. You may not build roads.

You may only build in the center of a hex, not on its edges as the Settler players do.

You may only build a new settlement on the tile where the Tribe marker is. Remember: move first, then build.

You may upgrade an existing settlement to a city without the Tribe being present.

You may not build a new settlement on a hex that has Settler-player objects (roads, settlements, cities) adjacent to it.

You may buy development cards.

You may trade with any player(s) AFTER you have moved the Tribe.

You may trade 4:1 with the bank on your turn. You may not use ports to trade.

Settler-players MAY build on tiles that have your Settlements/Cities on them. They MAY NOT build on the tile where the Tribe is.

E. On Every Turn

Your settlements yield the resource they are on whenever the number is rolled.

Your cities yield 2 of the resource they are on whenever the number is rolled.

You may trade with any player on their turn as long as they initiate the trade.

F. Winning

You win in the same way that the other players win: by accruing 10 Victory Points. You may accrue Victory points as follows:

-By playing Development Cards that have Victory Points on them.

-By building settlements (1VP) and cities (2VP).

-By defending territory (1VP).

-By acquiring the Largest Army tile.

You may not acquire the Longest Road tile, as you do not build roads.

G. Robber & Other Rules

If a rule’s change is not mentioned here, assume that basic Settlers of Catan rules apply to you. The hand limit, the rules about playing Development cards, etc. all apply.

If the Robber occupies the same hex as one of your settlements, it takes effect as if it were a normal Robber, and you may use Knights in the usual way to dislodge the Robber. The Robber does not affect the Tribe.

I’m just going to comment on the variant, although I enjoyed the article as well.

I’m concerned that the First Nations’ resources don’t scale very well in the mid-to-long term — that seems like a big disadvantage. If the First Nations build a city, it doesn’t provide as much advantage as when the others build a city, and a new First Nations settlement does not provide as much value as a regular settlement. That is mitigated by not having to build roads, and by the asymmetrical possibilities in the attack action, but I think eventually the Tribe gets ground down and out-resourced. The suggestion that comes to mind is to grant an extra Tribe move (and therefore an extra resource and more options for attack) with more settlements or cities, but that might be too powerful.

Also I think this leads to a massive arms race in development cards. At least, that’s what I’d do if I were a colonialist — the risk getting a city destroyed would be catastrophic. (Perhaps the attack should merely degrade a city to a settlement?)

Hi Frederic,

I like your thinking — the Tribe does become less and less effectively (comparatively) as the Settler players develop more cities and settlements. While my thought here is that it motivates the First Nations player to end the game quickly (a different play-style than is usual in Catan, highlighting the asymmetry in the game), I do like your fix. Another idea: Maybe tie extra Tribe moves to the construction of Settler-player cities, so that whenever a city hits the board, the Tribe gets some free moves? Not sure, I’d have to playtest it. Thanks for thinking about the game!

You could also give the first nations a resource for destroying a city, further incentivizing them to attack cities and level the playing fields. For instance, when you destroy a city, take any one resource that that city could produce. This number might need to be higher (2?) to make it balance.

I’m not sure what the whole point of this exercise is.

‘It became clear, at least to me, a white person playing this game in the U.S. in the early 2010s, that every game of Settlers of Catan re-tells the American myth of White European settlers stumbling upon a fertile land that was theirs by right, encountering no meaningful resistance, and acting on behalf of God and Country to develop economies, settlements, and cities in this “New World.”’

I’m a white person playing the game in the 21st C in Australia. A country which was considered to be Terra nullius. Which is a big island.

However I don’t think of Australia’s colonial history when playing the game.

The board looks nothing like Australia. The resource distribution don’t reflect that of the country, and the game doesn’t give any indication of an indigenous population in any way connected to the first inhabitants of my country.

Settlers is set up with each player populating the board with two settlements. It starts with a series of potential ports with which to trade. For me these things suggest the game is understood about the internal competition of native* peoples in a land.

Game elements like Cities, Monopolies, Armies, and so forth a much more evocative of topics like agrarian/industrial revolutions.

If I get both the longest road and the largest army am I more like protestants moving to the east coast of the US, or Spanish conquistadors in Texas, or perhaps the Romans, expanding an empire? If I make use of trading through ports and have a few cities built up am I more like the British in Australia, setting up penal colonies, or am I more like the Phonecians or Greeks?

And so on.

There are many ways you can look at Settlers and try and form a thematic understanding of the game.

I personally feel that we should try to understand the mechanics of Catan in a way that matches a view of the world that we are happy with. Rather than stretch out to find fault and thus miss out on a pleasurable game experience.

Hi Pasquale, thanks for reading this piece and thinking about its implications!

To answer your opening question (“I don’t understand what the whole point of this exercise is”), I’ll quote your own comment, with a brief clarification: “we should try to understand the mechanics of Catan in a way that matches a view of the world that we are happy with.”

This piece is my attempt to do just that: To create a Catan where I can comfortably play. When I began to feel uncomfortable playing Catan, the game ceased to be a “pleasurable game experience” for me, and that led me to craft this re-imagining of Catan that could be a pleasurable game experience. I was never “stretch[ing] out to find fault” in this exercise.

I’m not insinuating that every person in the world, or even every U.S. American, needs to play Catan the way that I do, so please, don’t feel that this piece is impugning the way that you play Catan.

However, I think First Nations of Catan is a fun variant, all ideological considerations aside, and I’d love if you tried it out sometime when you’re sitting down to play Catan.

Cheers,

Greg

Hi Greg,

You’re not really playing Catan. You’re just playing a game you made up that is like Catan, from Catan pieces.

And, not to be rude, but from what you’ve shared about your new game, I’m not sure why I’d want to play it when I feel like playing Catan. Its not the same game, and I want to play Catan because I want to play Catan…

I’d suggest you might just consider accepting Catan for what it is, and considering ways you can understand it differently to your initial reaction, or just playing another game.

Other games are great. You don’t have to play Catan if your worldview is getting in the way of enjoying it. Just play those other games instead.

Also, I would suggest that your ire/discussion is better directed at a game like Mombasa. Catan is largely abstracted and, title aside, seems to be more problematic by projection than by its nature. If it was called ‘The Germanic Tribes’ would you even have gone down this path you went down?

Hi Pasquale,

Re: Your first sentence: fair enough. I am also somewhat of a strict constructionist when it comes to games and their rules, so I understand the important distinction being made here. Perhaps I should have said “…needs to play Catan (and/or its variants),” or “…needs to engage with Catan,” etc. I don’t appreciate your use of the word “just” in this sentence, however, as, taken to its extreme, this position minimizes all games (for what is any game but “just” a game that [someone] made up from pieces?). As someone who makes and writes about games, this is a position I fight against daily.

Re: Your comments on what I play and do not play: This seems a bit off topic. My understanding of your comments was that you were concerned about why this piece was written, which I believe I answered in my previous comment.

Thanks for the advice to look at Mombasa. As a quick perusal of this journal shows, there are plenty of problematic games with plenty of good people investigating them. I’m glad you consider me up to the task.

Cheers,

Greg

My response was a little inconsistent. Generally speaking I feel that your reading of Catan is a stretch; that you’re doing a colonial analysis that engages with the game superficially – using the ability of any abstracted game elements to support whatever you want to load on to them, rather than a deeper breakdown of the unique elements of Catan.

I feel that you’re stepping off to your varient before you really break down you relationship with the game in detail and assess where it might fit and were it might be laboured, and as a result don’t offer much insight.

In this regard I suggested you look at other games like Mombasa, as I feel that they are much more interesting when it comes to looking at colonial attitudes and responses in games. And would give you greater scope to explore these issues that seem important to you.

In the end I didn’t learn much about Catan in this article, just about you and your varient design. That has value on its own, but Catan is not really a character of significance in your piece.

I wrote last year an article starting from the very same premise, but going into a different – and may be less constructive – direction. You can read it there :

http://faidutti.com/blog/?p=3780

Thanks for sharing this, Bruno! I particularly enjoyed the French-language pun on “Colon.” Speaking English, I never realized this overlap. Perhaps part of why the game was rebranded as “Catan”? I also like your application of concerns over exoticism to the past. Not something I’d thought a whole lot about, but something that board games as a whole are guilty of. Maybe there’s a game-design fix: Some sort of time-travel game like you suggest, buy I imagine it as a module that can latch onto other games, allowing the time-travelers to visit many different game-versions of the same exoticized locale!

http://bgg.cc/image/2560483/waka-tanka

What the heck?

A first answer here :

http://faidutti.com/blog/?p=4694

I plan to develop it one of these days, when I find time for it.

Did you actually read Said?

I read Orientalism and Culture and Imperialism. And I agree with most of it.

And you don’t find the art problematic in any way? I find this very odd.

I don’t say it’s not problematic – the very fact that there is discussion shows that there is a problem. After some discussions, I didn’t object it. I even find it quite good.

My two main points are

• as I explain in of the post scriptums to my original article, I don’t think we should abandon exoticism in games, but I think it’s important analyze it.

• The american indian imagery has a very different meaning in the US and in Europe, specifically in France, Belgium and Germany, where, for historical reasons, it has a very positive meaning.

From the discussions I’ve had with some american friends, it seems that it is mostly the covert art which is problematic in the US, while the cards are not. May be we should have changed the cover art for the US.

I would suggest that if the cover art is problematic it is problematic. I’m not sure how some European noble savage myth somehow grants it a free pass? Not knowing something is offensive doesn’t make it less offensive.

I’d say it’s an interesting problem that mostly shows the differences in appreciating these depiction between US and Europe. The art cannot be offensive or not per se – it is offensive or not depending on how you perceive the different elements of the caricature in it. I must say that I still don’t really understand why for the American eye the cover is offensive and the cards not.

It reminds me of another story, a few years ago, about an illustration for another one of my games, Isla Dorada. The US publisher asked the French artist to redraw part of it because it would be seens as racist in the US, but the French publisher had to ask the US one what part of the picture was racist. It happened that big lips in a caricature was a racist stereotypes in the US, while frizzy hair or excessively dark skin was not. Such codes are arbitrary, and we didn’t know about this one before, and had no way to guess it. Actually, the artist first thought that the racist stereotype was the bone in the nose, which is indeed borderline in Europe, but we were told this was not an issue in the US ;-), or far less than big lips.

That’s why I say that may be we should have changed the cover for the US, but that the art for this game is not offensive per se.

No. They not arbitrary. They’re based on a history of racist stereotyping.

Is Tintin not offensive in regard to Japanese people, just because it was published for a European audience? If I make racist jokes to my friends who aren’t of that race, do they jokes cease to be racist?

That Europe doesn’t have a significant enough population of Native Americas to cause this cover to be an issue there doesn’t mean it doesn’t perpetuate racist stereotypes. The world is a single place, everything is connected.

What shows it’s arbitray is the strong lips example – no black in Europe will find this more racist than fizzy hair. Cartoons are caricatures, and therefore simplistic, but bot necessary racist. They often are, but which stereotype becomes racist and which doesn’t is arbitrary.

I agree with you on the fact that we tend in Europe to forget that American indians are still a living culture, mostly because none of us has ever met a single one. I admit that this might be a problem with my game’s theme, and that for this reason old greeks might have been a wiser choice. But the problem seems to be the art more than the theme, and I don’t find the art disparaging. What surprises me is that I had another game with an american-indian theme a few years ago, Tomahawk, with the same kind of graphic treatment, which didn’t seem to raise any problem.

BTW, what makes Tintin offensive for Japanese people is less the racist stereotypes, even though they are undoubtedly there but not taken very seriously, than its pro-chinese political stance.

What I want to say is that

• yes it’s exoticism

• as I stated in my article, I don’t think we should give up exoticism, because the very simplistic nature of boardgames need it.

• the only problem is to avoid what is clearly offensive

• from Europe, it’s almost impossible to guess what will or will not be deemed offensive in the US

2. I don’t think you’ve made a strong argument for this.

3. It’s not hard, consult the minority groups whose cultures you’re appropriating and get some feedback.

What should the First Nations player do with the Road Building development card? It would be frustrating to buy a card that has literally no utility for that player.

I propose possible amendments for the First Nations player:

1) move the Tribe up to two spaces, or

2) play this card instead of paying to attack with the Tribe.

@Greg, what are your thoughts?