How do theater games help make meaning for performers and audiences? I came to this question through my work on the production Charlotte Charke/Mr. Brown, an experimental musical theater piece about the 18th century London performer who lived much of her1 life dressed in men’s clothing. This theater piece was devised using extensive game play. Theater games drawn from Viola Spolin and Keith Johnstone, theater practitioners who developed games to teach acting and improvisation, were used during the rehearsal process. We also made up new games to help us embody our engagement with issues that arose from the script, and even played some of these games in front of the audience during the final performance. However, the playing of our games created such an intensely bonded community that the energy and pleasure of the play was not always communicated to those outside of the playing circle. We began to bridge this gap in meaning through traditional performance techniques such as enlarging the actors’ movements and voices to fill the performance space, and extending their energy and awareness outward. The players stepped beyond fourth-wall based Stanislavskian acting techniques as they learned to include the audience, conceptually, as players of their games.2 This essay has been prompted by the experience of writing and directing Charlotte Charke/Mr. Brown; it is a critical analysis that shows how joy, spontaneity, and meaning are built into theater games.

Theater games developed in the twentieth century as a technique for keeping child-like joy and spontaneity in the play of actors of all ages. Viola Spolin developed her use of theater games during her work in the Works Process Administration (WPA) drama program, adapting the games she played with immigrant children in settlement houses for use in her adult acting classes. Acting teachers and directors today use Spolin’s Improvisation for the Theater and Theater Game File as resources for their warm-ups and actor training.3 Spolin’s son, Paul Sills, used her games to develop the improvisations which are performed at The Second City in Chicago. Since 1959, Second City has trained generations of comedians, from Anne Meara and Jerry Stiller to Tina Fey and Keegan-Michael Key, and the improvisational techniques developed there formed the basis of shows such as “Saturday Night Live” and “Whose Line is it Anyway?”. The development of Theatresports, an influential improvisational comedy troupe in Britain, arose from Keith Johnstone’s theater game work. Johnstone’s work also emphasized spontaneity and his book, Impro, laid the foundations of status work, which I address later in this essay. Both Spolin and Johnstone were attempting to get their students to be in the moment, moving away from the more presentational styles of acting which were prevalent in the early-mid twentieth century. The problem I encountered with my cast was that they became so involved in the moment that they were creating meaning for themselves, but not for the audience. Theresa Robbins Dubeck describes Keith Johnstone’s exhortations to actors to pay attention to the audience in terms of staying withing their ‘circle of probability,’ but this addresses narrative scene-making, and we were performing the games as a counter to narrative flow.4 How could I help my actors include the audience in this type of meaning-making without losing any of their joy and spontaneity?

Half of Mr. Brown consisted of traditionally scripted scenes, and in the development and rehearsal of these scenes, we used theater games in equally traditional ways. According to acting coach Viola Spolin, “games release spontaneity and create flow as they remove static body movements and bring the actors together physically”.5 Tsunami was one of the games we used to work on these goals. This game begins with the players standing in a circle. One player initiates a brief sound and movement that is repeated quickly by each person around the circle. Once it has traveled the whole way around and been repeated by its initiator, the next person in the circle comes up with a new sound and motion. The game continues until all players have initiated. Tsunami works on several levels; it encourages spontaneous reactions, makes the players use their bodies and voices in unaccustomed ways, and has a strong ensemble-building effect. Once an ensemble has embodied these spontaneous reponses to each other in a game like Tsunami, they are able to bring that sense of spontaneity into their scripted dialogue and carefully rehearse movements, allowing the audience the illusion of unscripted conversations and interactions.

As we rehearsed the scripted scenes in Mr. Brown, we used theater games to heighten our meaning making. Keith Johnstone developed status work to help his actors speak, not theatrically, but “like life as [he] knew it”.6 I attempted to use his work to heighten the theatricality of the actor’s bodies in order to add layers of meaning to the scene. In one scene where Charlotte, an 18th century actress at the Drury Lane Theater, is visited in her dressing room by a group of noblemen and by her father, the owner/manager of the theater, the actors were having a hard time developing new physical habits. I asked the actors to play a game in which they competed, without speaking, for high or low status, thinking about what their physicality was saying about their relationship to each other.7 Is the hand on the shoulder a friendly gesture or a patronizing one? Is eye contact always indicative of high status, or can you sometimes show more status by refusing to look at the other person? Through playing competing status games, they were able to achieve an embodied understanding of these subtle differences. When we turned back to the scripted scene, the noblemen were able to physically express an exaggerated high status. Charlotte’s father, Colley Cibber, was able to demonstrate, without saying a word, his lowered status compared to the noblemen and his higher status over Charlotte. The actress playing Charlotte physically expressed her discomfort with her status as a woman in eighteenth century society by competing for status with her father and lowering her status toward the noblemen until their sexual harassment became too much for her. The physicality these student actors found through the status games was large and open enough to make the situation and the stakes clear to the audience. We had used Johnstone’s games to move in the opposite direction from his intended purpose; the scene had gained meaning by becoming meta-theatrical, by pointing at the physical performances that each character had to constantly generate in order to maintain their high or low status.

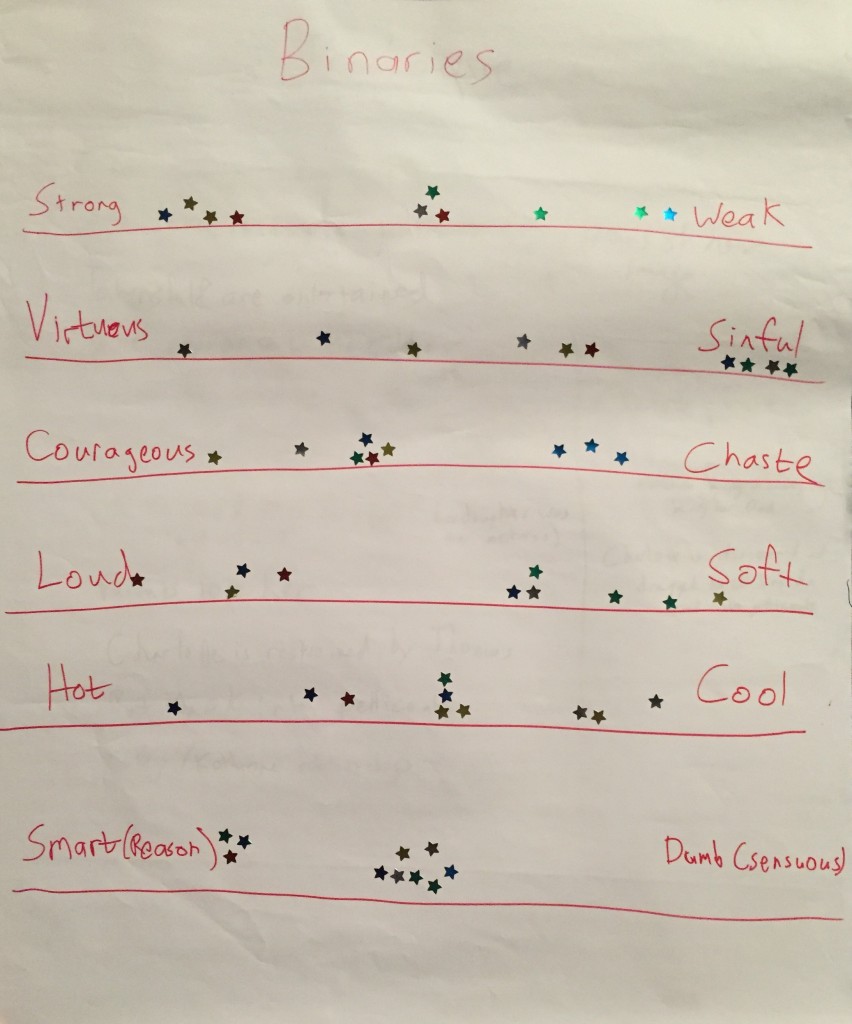

In addition to the games which had been developed by Johnstone and Spolin, I had to develop some of my own to help foster critical inquiry of gender issues within the group. For example, early in the rehearsal process, we made a list of adjectives that our culture views as gendered, and I gave the cast foil stars to stick on the line between the oppositional adjectives to represent themselves. The actors spent upwards of an hour playing with this chart, and we held long discussions about what this meant for them and their places on the gender spectrum. At a later rehearsal, I wrote each of these adjectives on a big piece of paper and placed the papers in a circle around the rehearsal space. I asked them to pick a piece of paper, and choose a repeated motion and a sound to illustrate the adjective. We played this for a while, and then I asked them to move from each adjective to its opposite, morphing the motion/sound gradually as they moved across the room. They began moving in groups as they played, so I asked them to move as one group, imitating one another until they found a unified motion and sound for each adjective. After a couple of hours of play, we had developed a game/dance which we performed in the show each night. This game helped the cast reach an embodied understanding of gender binaries, which informed their work on the rest of the show. Although they performed this game each night with joy and spontaneity, and audiences responded positively to it, the meaning of the dance was not overtly clear to many spectators.

Meaning is generated differently when the size of the room and/or the number of recipients changes. Think of the different levels of energy required to communicate in a one-on-one conversation in a quiet room, and the energy required to communicate a similar meaning (without technological enhancement) in a large auditorium to several hundred listeners. As we moved from our rehearsals into our performance space, I knew that the games as they had been played in a small rehearsal room needed to change in order to fit the one hundred fifty seat thrust theater. There were two goals I needed to accomplish. First, with an awareness of the theatrical space as a new body being added to our community, I wanted the the cast to integrate the building as part of their ensemble. Second, I needed the cast, as performers, to open up their bodies, voices, and awareness to fill the bigger space. In order to accomplish the first goal, the first thing we did in the theater space was to play a game of sardines. Sardines is a reverse hide-and-seek game; one person hides, and everyone else tries to find them and squeeze into their hiding place with them. After ninety minutes of play, the cast was thoroughly comfortable with every inch of the theater space, and the ensemble had embodied their integration. In order to accomplish the second goal, I expanded our warm-up circle game of tsunami. We had played tsunami in our small room in an intimate circle. In our new space, we played it in a circle which encompassed the back rows of the audience seats and the farthest reaches of the stage area. Playing this way helped them expand their physicality, vocality, awareness, and energy to fit the new, larger theater space.

Despite these improvements, some problems remained. Specifically, the actors weren’t yet communicating meaning outside of their ensemble. At a rehearsal, one observor mentioned that, during the game scenes, the actors seemed to be playing for themselves. Realizing this was true, I asked the actors to make the games bigger physically, vocally, and to expand their energy to the walls as they played. They did as I asked, but it still wasn’t quite enough. They had built such an intimate ensemble, what play scholar Johan Huizinga would refer to as, a “feeling of being apart together,’”8 that they made no connection with the audience. During one of the next rehearsals, there were about five observers present, mostly members of our tech crew. I asked them to sit throughout the house, and then asked the players, during the game, to be aware of one specific body in the house at a time, extending their awareness and energy to that body, and then to another, conceptually including them in the playing of the game. Our audiences reacted with laughter and tears, reporting visceral reactions to, and feelings of bodily engagement with, the interludes. The players, without losing the joy and freedom of their play, managed to include in their circle the other present bodies.

Throughout the rehearsal process our use of games as warm-ups, scene builders and problem solvers allowed the cast to be joyful in their play. Their embodied practice of spontaneous interaction helped them bring that spontaneity into even the most scripted repetitions. They discovered meaning through their playful explorations of the issues raised by Charlotte Charke/Mr. Brown, and learned how to communicate that meaning across large spaces and to large numbers of spectators. The game playing and meaning-making we did was not constrained by a narrative format; we were exploring issues by playing with our bodies and voices without concern for logical structure or linguistic communication. Part of our work was to point at the performance that Charlotte constantly maintained, whether as Charlotte or Mr. Brown, and so we needed to point at our own performance in a way that was neither presentational nor attempting to be life-like. When Spolin speaks of “increasing of the individual capacity for experiencing” through game play, she is speaking of the actor’s capacity for experience. We increased the audience’s capacity for experience, as well, by including them in our games. The players needed to be in the moment, aware of the moment, and, in order to allow the audience inside of our circle of meaning, include their bodies in each moment of awareness.

–

Featured Image “Royal Opera House,” by David Woo @ Flickr CC BY-ND.

–

Lisa Quoresimo is a theater director, playwright, and composer, currently researching the intersection of voice, music, theater, and sexuality. She is currently a doctoral student in the Performance Studies Graduate Group at UC Davis.