Introduction: Definitions and Method

Tabletop games and stories have shared across history many types of interactions. A game can appear in a narrative text as an object and an activity represented in the setting of a story, and when that is the case it can be invested with symbolic, social, and psychological implications. Good examples are the games of Chess played by the characters in Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, Marino’s epic poem Adonis, or Stefan Zweig’s novella The Royal Game; the game of Go at the heart of Kawabata’s novel The Master of Go, or the tabletop wargame around which Bolaño’s novel Third Reich revolves. Stories can host fantastic variants of known games, like the Tri-D Chess of Star Trek or the Wizard Chess in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, or can devise completely made-up games, like the supremely complex alien game that is the main theme of Banks’ novel The Player of Games.

Alternately, a narrative can use mechanics from games as an inspiration not for content but for structural and organizational principles. We see this in Italo Calvino’s The Castle of Crossed Destinies, inspired by the combinatorial element of card play, or in the poem collection by Jacques Roubaud titled E, which features 180 texts corresponding to the white pieces of Go, and 181 texts corresponding to the black pieces. Roubaud’s introduction explains that the mobile and game-like structure of the book allows the reader to experience the texts in different ways through different arrangements of the components.

In some cases, a game and a fictional narrative can coincide, in the sense that a game can employ a text as its main or sole equipment. A perfect example is the gamebook, which had its heyday in the 1980s thanks to series like Fighting Fantasy; or the electronic text adventure, which also flowered in the 1980s; or the paragraph-based board game, originating from the 1981 game Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective and experiencing a true rebirth these days. Depending on how one looks at them, these artifacts are games that construct stories, or stories in which the reader makes decisions that will lead to a condition of victory or defeat. In gamebooks, text adventures, and paragraph-based board games, the narrative and the ludic aspects are entirely coterminous, and they contribute to create rich and nuanced storyworlds. Fiction itself, in the 20th and 21st centuries, has developed a more marked predilection for intricate worldbuilding than ever before. Building upon this trend, gamebooks, text adventures, and paragraph-based board games have learned to employ verbal means to represent fictional realities that the player will deal with through the application of game mechanics like rolling dice or selecting moves. The resulting narrative is “a cyclical process afforded by the representational, mechanical, and medium- specific qualities of a game, and actuated in the mind of the player,” with every verbal bit and ludic mechanic of the artifact contributing to the expansion of the storyworld.

Some games and texts exist, however, whose shared storyworlds remain partially independent from one another. An example is a family of designs that scholars like Lancaster, Jones, and most notably and most recently Booth, have called “paratextual games”. These games are heavily based on preexisting, non-playable, non-interactive narratives, which they implement in considerable detail. Paratextual games borrow thematic elements from their sources, and pair them with mechanics that mirror the inner workings of the original stories, like in games based on A Song of Ice and Fire that incentivize Machiavellian scheming. With games of this kind, the player can “slow down, cut up, stop, recreate, reform, recuperate, restore, and otherwise play with” materials from the original stories, in turn creating variations around the original plots, and in a sense generating performative fan fiction. Paratextual games and their sources are examples of artifacts that extend into a shared storyworld (with the same characters, settings, and concepts) while still retaining individual identities, since the narratives told by the games can differ considerably from their blueprints. These very differences justify the labeling of such games as “paratextual” in the original sense of the term proposed by Genette. Paratextual elements are not just peripheral or ancillary satellites orbiting a text, and rather function as conceptual thresholds through which the text is accessed, perceived, and interpreted. Games that create alternative performances of a storyworld can in fact offer exceptional insights about the originating text by allowing us to examine a range of what-ifs that, in turn, may cast new light on the fictional events that did occur in the story. The game is the prism through which the straight narrative progression of fiction is refracted into a dizzying kaleidoscope of stories.

The main object of the present essay is a category of intersection between stories and games that can be thought of as the complementary opposite of “paratextual games”, and that I define as “paraludic literature.” With this term I indicate “traditional” (linear, non-playable, non-interactive) fiction that takes place in storyworlds originally created for tabletop games. The origin of this category of expression is quite recent. It wasn’t until the 1970s, with Dungeons & Dragons and role-playing in general, that games became effective sources of vividly represented fictional content. Only then did hobby games start being intensely thematic, to the point of developing detailed, complex, expansive, and immersive settings. Role-playing also introduced the focus on unique and particularized characters which is one of the key elements of fiction, and that traditionally had not been a major concern in gaming.

Early paraludic narratives emerged as a natural, even predictable extension of role-playing games (RPGs). Primary materials for these games are not just miniatures and maps, but manuals describing fictional places, characters, objects, cultures, and practices – the very same materials fiction is made of. Role-playing games are, after all, a type of performative and interactive storytelling, with imaginary actions proposed by the players, and, if accepted by the referee, integrated within the developing setting of the game. Between the 1970s and 1980s, many designers were inspired by the story-driven approach of role-playing, and proceeded to apply it to tabletop board games, turning what used to be abstract, partitioned play areas, into vibrant and compelling settings. In my book Storytelling in the Modern Board Game I discussed extensively of how these games can generate stories during gameplay. In the present essay, I shift my attention to elaborate game settings employed outside of gaming as a framework for traditional linear fiction.

This phenomenon, per se, is not extraordinary, and it follows the spreading across media of all sorts of successful stories – like for novels turned into movies, toys, or comics. Still, the fact that thematic tabletop games can now act as generative sources of fiction raises several questions and issues, and requires an examination of the modalities and effects of the exchanges between linear texts and playable storyworlds. Similar considerations could be made for digital games, which also have spawned many examples of non-interactive fiction in literature and film. In order to define a manageable field of inquiry and avoid excessive generalizations, however, this essay will deal exclusively with paraludic literature originating from physical tabletop games.

Practical reasons of the same kind force me to examine my topic from a somewhat narrow perspective. It would be of great interest to study the material history of paraludic texts from conception, production, distribution, and so forth. It would be equally fascinating to develop an ethnographic interpretation, incorporating responses from a large number of readers and players. Expanding my present discourse to these areas of inquiry, however, would better suit a book (and I don’t exclude that I might conduct such a work in the future). For the time being, I will confine myself to working within a mainly semiotic and user-oriented line of analysis, focusing on the range of uses and interpretations that paraludic texts may be subjected to within the conventions and expectations of the cultures that originate them (in this case, hobby gaming and genre fiction).

I will also focus strictly on fiction originating from intensely thematic games. After all, in order to generate fiction based on its storyworld, a game needs to have a storyworld to start with. The flimsy setting of the game Clue, for example, would hardly allow any fiction to truly take place in it. Besides not being very detailed, it is a setting in which detectives move at a random speed that does not mirror how sentient beings operate; in which forensic science can’t distinguish a gun wound from a strangulation bruise; in which “not only can you win by proving that you committed the crime, you can accuse yourself and be wrong, and will lose the game as a result. As a game mechanic this works, but in story and genre terms it is a tale told by an idiot.” Unsurprisingly, then, the movie Clue (1985) and the IDW comic of the same name (2017-present) have very little to do with the game other than the title and the names of the characters. Evidence is in the fact that if one changed titles and character names in the movie and the comic series, the game source would become unrecognizable, and the stories would appear to be simple parodies of classic mystery like Murder by Death (1976). Conversely, it’s believable that if one changed the titles and every name in the novels of A Song of Ice and Fire (1996-present), the TV show Game of Thrones (2011-2019), and the Fantasy Flight board game Game of Thrones, most users would still be able to see the robust connection and shared storyworld of the artifacts.

Historical Overview

Historically speaking, fiction based on RPGs and set in popular RPG worlds has been around since the 1970s. Short fiction contained in sourcebooks has always been a preferred method to give players a sense of the storyworld’s general atmosphere, showcase the narrative potential of the game, and feed the players’ imagination.

As for paraludic literature published outside of role-playing sets, Flying Buffalo opened the way with a series of solitaire adventures published from 1976, and based on the role-playing game Tunnels & Trolls. While separate from the main game, those stories still required knowledge of the T&T rules in order to be fully experienced, and they are therefore to be seen mainly as narrative-based game expansions. In the 1980s the publisher Corgi reprinted some of those adventures in volume format and with an abbreviated version of the game rules, turning them in the process into gamebooks proper – that is, fully self-contained works of fiction.

In 1982, TSR released the series of interactive branching novels Endless Quest, which was based on storyworlds from TSR’s role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons. These books did not contain any game mechanics, and in fact did not require any knowledge outside the work itself to be understood and appreciated. Many of these books, moreover, only contained a limited number of choices for the reader, and had fairly linear narrative trees. All of this meant that, while being interactive, and therefore not fully fitting our definition of paraludic literature, Endless Quest books had definitely shifted the focus of the experience from game to story, representing an interesting transition in the formation of our genre.

In 1984 TSR went a step further when it expanded their offer of game-based fiction with the Dragonlance series, which may have been the first project in which a playable storyworld gave origin to a large canon of linear narratives. Developed by Laura Hickman, Tracy Hickman, and Margaret Weis, and expanded by a plethora of authors, Dragonlance consisted of non-interactive fantasy fiction based on the characters, settings, and tropes of D&D, and was successful enough to spawn well over 100 novels between the 1980s and early 2000s. In 1988 the world of D&D was also employed as a setting for the successful Legend of Drizzt fantasy series by R. A. Salvatore, currently still in progress, and counting over 30 novels. Further linear fiction stemming from the game-based novels includes The Legend of Drizzt comics published by IDW since 2010, and the Italian parodic webcomic Drizzit, published by Bigio since 2010. Things came to full circle when Salvatore’s novels, in turn, became the subject of the board game Legend of Drizzt (2011).

Along the years other works of fiction would follow suit and ground their narratives in the world of role-playing. Other examples include the Tékumel Novels (5 books between 1984 and 2003), notable because based on the early RPG Empire of the Petal Throne by M. A. R. Barker; several series based on Battletech, comprising over 100 novels between 1986 and 2008; the Shadowrun Legends series based on the RPG Shadowrun, published between 1990 and 2001 by Roc, and recently republished in e-format by Catalyst; the Pathfinder Tales series based on the massively popular RPG Pathfinder, debuting in 2010 and still expanding to this day.

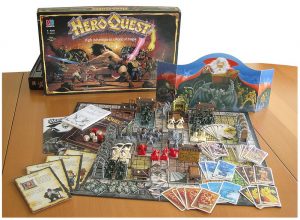

The next manifestation of this phenomenon is narrative texts spawning from board games, precisely at a time when games had started including complex and detailed storyworlds. One could hypothetically write a novel “set” in the “world” of Chess, but a lot would need to be added to arrive at fully fleshed characters and narratively significant interactions. Even Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass is mainly set on a giant chessboard rather than “in” Chess. But to turn a board game like HeroQuest into a novel, all one needs to do is to immerse oneself into its tridimensional and multilayered setting, which already comes loaded with short paraludic fiction embedded in the scenarios. Next, one can appropriate the heroes, monsters, locations, atmosphere, culture, and general psychology of the game, and rearrange them according to the necessities of a plot that the game did not include originally.

The board game HeroQuest represents an early implementation of this idea. Published in 1989 by Milton Bradley, HeroQuest quickly established itself as a sort of D&D-in-board-game-format, and one that would allow its players to enjoy the excitement of exploring a fantasy world at a fraction of the rules overhead of an RPG. HeroQuest was met with great success, which predictably lead to the publication of several expansions and ancillary products. One such product was a line of gamebooks that may be the earliest example of books coming out of a board game’s original setting. The first book in the series was The Fellowship of Four (1991) by Dave Morris, in which the reader controls the same team of four heroes that are found in the game. The following HeroQuest gamebooks, The Screaming Spectre (1992) and The Tyrant’s Tomb (1993), both by Morris, cast the reader in the role of only one of the heroes (a wizard and an elf, respectively), and again offer an opportunity to explore the storyworld of the board game.

1993 saw the publication of a transmedia project that also included the novelized version of a game storyworld. The project included the coordinated production of a large fantasy board game, Legend of Zagor, designed by Ian Livingstone and published by Parker Brothers; a gamebook by the same title signed by Livingstone, but penned by Carl Sargent; and four non-interactive novels forming the Zagor Chronicles, written by Livingstone and Sargent (under the pseudonym of Keith Martin): Firestorm, Darkthrone, Skullcrag, and Demonlord. Both the gamebook and the Chronicles novels offer ways to experience the setting, characters, and situations of the board game in literary format, with different degrees of agency and interactivity. We can also verify that board-game-based fiction shared the trajectory of gradual shift from game to story we saw in RPG-based stories. There we went from game (D&D) to gamebooks (Endless Quest), to non-playable books (Dragonlance). Here the same occurred with the game HeroQuest being followed by HeroQuest gamebooks and later Zagor Chronicles novels.

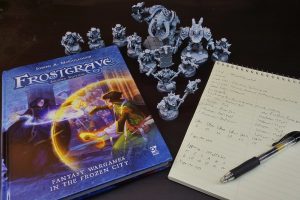

Among others, notable examples include novels and short stories based on the horror board game Arkham Horror, the cyberpunk board game Android Netrunner, and the tabletop wargames Warhammer, Warhammer: Age of Sigmar, and Frostgrave. This last game, at the time of this writing, has been the inspiration for two collections of short stories and four novels that fully belong to the genre of paraludic literature. Given the manageable size of this production, stories set in the world of Frostgrave provide us with an excellent case study to investigate the functioning of paraludic literature up close. The fact that both the game and the texts are very recent, furthermore, can help us gain a keener insight about cultural, ludic, commercial, and artistic mechanisms currently in act. In order to do so, it is vital that we start by discussing Frostgrave both in its general profile and in its potential as a narrative engine.

Frostgrave: The Game

Frostgrave, created by Joseph A. McCullough, and published by Osprey in 2015, is a fantasy miniature wargame that represents terrestrial battles between opposite warbands of magic users and mercenaries. The game revolves around the sprawling city of Felstad, a once prosperous center of study and practice of the magical arts. A long time before the opening of the game, an unspecified magic accident altered the climate of the region catastrophically, burying Felstad under an impenetrable layer of ice and snow, and earning the city the ominous nickname of “Frostgrave”. The premise of the game is that the ice has finally started to thaw, and the reputation of the city has attracted adventurers in search of treasure, magic users eager to study the arcane arts of Felstad, and mercenaries willing to work as bodyguards. Boomtowns have sprouted around the city, and they function as starting points for raid-style explorations. In a fantasy world, however, a ghost city is not necessarily uninhabited. Felstad is populated by undead creatures, constructs animated before the great glaciation, otherworldly entities pouring in through magic gates, and wild beasts, common monsters, and criminals that have recently moved in. Other bands of adventurers of course represent as serious a threat as the hostiles above.

In terms of narrative potential, Felstad/Frostgrave represents a bottomless reserve of ideas and situations. It is a lawless fantasy Far West in which the players may have to deal with a new horror that just awoke from a tomb (as in the expansion Thaw of the Lord Lich); may discover new buildings or entire areas of the city (as in The Maze of Malcor); may decide to enter unexplored systems of tunnels under the city (as in Into the Breeding Pits), or venture into the regions surrounding Felstad (as in Forgotten Pacts).

This variety of situations is made possible by the fact that Frostgrave is a miniature wargame. As it is typical of this style of game, its published materials consist mainly of rule manuals and sourcebooks, and the players must provide their own equipment in the form of dice, tokens, measuring tools, terrain features, miniatures representing the characters, and any other item they want to place in the battlefield. This means that players do not have to set their games in a predetermined and unchanging play area (like in traditional board games), and are free to experiment with different types of landscape and situation each time. Consequently, the game displays virtually endless representational potential. Anything the players use to play according to the rules of Frostgrave, simply becomes a legitimate instantiation of Frostgrave. The burden of having to procure all the components and to learn unique scenario-based rules is therefore abundantly counterbalanced by boundless flexibility and customizability, which allow the players to tailor each iteration of the design to their taste and playstyle.

The representational freedom embedded in the game system is also what allows it to develop complex, overarching narratives. Fiction is always a form of semantic progression – about something that was A, then becomes B, experiences C, develops into D, etc. Most traditional games, on top of being rather abstract, always start from the same game state regardless of what happened in previous sessions. A story based on a string of sessions of Monopoly or Goose would resemble in structure Groundhog Day more than The Lord of the Rings. On the contrary, miniature wargames, not being tied to a fixed set of physical elements, can weave scenarios together in a progressive narrative by adding, removing, and replacing components (and therefore themes) as needed. This way, each session can start where the previous one ended, like chapters in a novel building upon one another. A fantasy wargame may feature a scenario in which the heroes learn about the existence of a golem, then another in which they study that very golem, and finally one in which they face the golem and defeat it. This is precisely the structure of a mini-campaign for Frostgrave called Hunt for the Golem, whose scenarios, when played in order and with the characters and resources from previous sessions, form a narrative far more developed than the sum of its parts. Such expression of narrative functions through gameplay was after all one of the programmatic intentions behind the design, as stated by the author in the original rule set:

Although one-off games can be fun, it is by combining games into an ongoing campaign that you will get the most out of Frostgrave. By playing through a campaign, you will be able to watch your wizard grow in power and experience. You can also spend the treasure you acquire in games to expand your warband, acquire new spells, and even establish a base of operations, equipping it with such resources as magic laboratories, summoning circles, and celestial telescopes.

As for gameplay, in Frostgrave each player controls a warband comprising a leading magic user, an apprentice, and a group of bodyguards. While each player operates all the miniatures in their party, the game encourages a strong degree of identification with the main magic user, who acts as the avatar of the player in the world of the game. This type of arrangement has the considerable advantage of strengthening the emotional bond between player and character while preserving the tactical flexibility afforded by the presence of multiple figures. Identification with the leading figure is also assured through the high degree of customization allowed by the system, which makes it possible for players to create highly individualized wizards, but not equally detailed apprentices or mercenaries. This is achieved by having ten different schools of magic that the leading wizard can belong to (such as Chronomancer, Elementalist, Enchanter, Sigilist, and so on).

Furthermore, each wizard can have secondary specializations in other schools, and is allowed to cast spells from those schools at an increased cost in game resources. The effect of this “minor degree” is both a further level of individualization, and a mechanically solid system to generate meaningful in-game decisions. Each spell in fact has a “casting number,” and spells of one’s own school have lower numbers than those in secondary schools. Before casting a spell a player must roll a die, and the spell counts as successfully executed if the result is equal to or higher than the casting number. In case of a failed roll, the player may reduce the magician’s health to add points to the die roll (representing the extra effort it takes to complete the ritual). The wizards are therefore interesting to create, due to their level of granularity, but also to play, as the owner must constantly assess the right time to invest in riskier and more costly spells, which may nevertheless be beneficial under specific circumstances.

Following the success of Frostgrave, Joseph A. McCullough released a sister game called Frostgrave: Ghost Archipelago, which features warbands exploring a series of mystical islands that magically appears in the southern seas only every couple of centuries. In Ghost Archipelago players experience a strikingly different setting from that of the original game, with luxuriant jungles in lieu of frozen wastes, and a complete new range of monsters, adversaries, and items. Playable characters have changed too, with the main character in a party now being a Heritor (a superpowered being) helped by a Warden (a nature-based wizard) and a crew of helpers. The game also includes an overarching narrative, in which the players have the ultimate goal of finding the fabled Crystal Pool, toward which the Heritors are irresistibly drawn. Each session of the game is meant to be understood as a new step toward that goal – almost a new chapter in a quest.

Ghost Archipelago is described in the rules as “a narrative wargame”(5), and replicates its predecessor’s emphasis on customizable warbands exploring exotic places, raiding forgotten treasures, and fighting for dominance in the battlefield. The game has also received several expansions, such as Lost Colossus (2018), which includes a 10-scenario campaign, and Gods of Fire (2018), which has a system to generate tribal characters, plus three campaigns.

Frostgrave: The Stories

Now that we have a general idea of the play experience Frostgrave generates, we can have a better understanding of the fiction that has been designed around the game and its storyworld. We will base our analysis on the short-story collection Tales of the Frozen City (2015), by various authors; the novels Second Chances (2017) and Oathgold (2018), both by Matthew Ward and based on the original game; Tales of the Lost Isles (2017) by multiple authors, Destiny’s Call (2018) by Mark A. Latham, and Farwander (2018) by Ben Counter, all based on Ghost Archipelago.

The first thing that emerges from reading these works is that authors of game-based fiction face the absolute necessity of connecting their creations with the original source materials, which are likely to have attracted many of the texts’ readers in the first place.

The author must therefore perform the same tasks of the player who prepares a game, selects the physical equipment that will materialize gameplay, and performs the in-game actions that will turn the initial configuration of pieces into a sequence of events. The player uses physical pieces and the author words, but the results must converge toward the perception of an immersive setting and a compelling storyline.

This process is of paramount importance when it involves the central characters of game and books. Players shape their avatars according to the rules of the game, and embody them by selecting and customizing specific miniatures. The sculpt chosen for the main magic user defines the gender and general appearance of the avatar; the paints selected for clothes, skin, and accessories further define the character in unique ways. Equally, the author of a Frostgrave story must select character types from the ones available in the original sourcebooks, and then turn them into unique and well-defined individuals. The verbal medium, furthermore, allows the creation of complex backstories that can give a character’s actions a deeper level of resonance and meaning. While players have been known to create backstories for their heroes, this is simply not commonly done at a comparable level of detail. Players want to play, so it is no surprise if the biography of their characters develops almost entirely through gameplay, and therefore linearly, in a forward-moving timeline, through a sequence of game sessions. It is mainly the author who will jump back and forward in time, compare past and present, and alternate between different timelines.

Authors of Frostgrave fiction must also connect with other key thematic elements of their foundational materials. This requirement may function both as a source of inspiration and as a set of limitations. It would be unthinkable, for example, to have a Frostgrave story that does not reference the schools of magic at the very core of the game. Accordingly, we find in Frostgrave fiction characters who specialize in the styles of magic in the game like the Chronomancer, the Enchanter, the Illusionist, the Sigilist, the Necromancer, or the Thaumaturge. The same can be said for the branches of natural magic in Ghost Archipelago. For instance, a Storm Warden plays an important role in Latham’s Destiny’s Call; in McIntee’s Uncertain Fates we find a Beast Warden and a Storm Warden, while Page’s The Clockwork Chart features an Earth Warden prominently.

Another element of the game that also populates Frostgrave-based fiction is its ample cast of adversaries. Examples include the snow troll, the golems that play important functions in Oathgold, or the reindeer-men known as rangifer, introduced in the game expansion Thaw of the Lord Lich, and receiving considerable attention in the novel Oathgold. Similarly, the Ghost Archipelago game provides the stories with a colorful bestiary comprising giant snakes, giant lizards, snake-men, panthers, elephant-men, dust devils, semi-ethereal skeletons called Spirit Warriors, and a giant saurian called Monarch. The stories set in the Ghost Archipelago game also feature the Bronze-age-level civilization of the Drichean, which are a group of native tribes that was first introduced in the original game manual, and will be the main subject of an upcoming expansion. In this last case, the stories based on the game represent a sneak peek at materials that are not yet available for play at the same level of detail. While advertising a future product, these stories show that the connections between game and texts do not have to go only in one direction (from rules to fiction), and can in fact create a more intricate system of exchanges between the two.

Not all transfers from game to fiction are simple and smooth to execute like in the cases above, however. In some cases, elements from the game must be adjusted or reframed to meet the conventions of fantasy fiction and the expectations of the reader. We saw that in Frostgrave a player must usually roll a die to cast a spell, and in the context of the game this is a desirable mechanic because it adds uncertainty to gameplay. In fiction, however, a magic user that is never certain to cast a spell successfully would come across as terribly incompetent, and is likely to be found only in parodic or ironic treatments. Accordingly, the magic users in Frostgrave fiction appear to be more powerful than their gamic counterparts, and their magic is immensely more reliable. These characters may worry that the spell won’t have the desired outcome, but they don’t usually fear that they won’t be able to cast a spell at all. This is the situation of an archer who may fear to miss the target, but not to fail to release the arrow. Equally important, in the rare cases from the fiction when spells do collapse while they are being cast, the occurrence is always given an explanation. When a wizard fails to cast a spell in Page’s The Devil’s Observatory, the author justifies the event by blaming it on the character’s lack of practice. When the protagonists of Second Chances doubt their spellcasting, we are told that the cause is extreme exhaustion.

A different kind of exchange between game and fiction can be found in the detailed representation of elements that the game manuals only outline, but that can and at times must be rendered in further detail in the stories. This is a matter of filling the gaps and adding finishing touches to an already vivid world – but one that is not equally detailed in the same areas where a story may need greater definition. The advantage is that after experiencing the themes of the game in stories that present them at a higher degree of vividness, the reader can return to the game with a stock of powerful mental images to project onto the play experience. Once seen through the vibrant filter of fiction, the situations created in the game can also be perceived as richer and better fleshed-out.

The best example of this process is possibly the representation of spells in the game manuals and in the works of fiction under exam. Often the spells cast by the characters in the stories match the ones described in the game quite closely, like in a scene in Second Chances where the effects of “Decay” are described in great detail; or in the short story Mind over Matter, where “Transpose” is key to the resolution of the plot. The very fact that an informed reader can trace an unnamed spell from the fiction back to one in the manuals is a sign of how closely one mirrors the other.

In the description of the casting process, moreover, the prose can fill in the blanks that were left in the manuals. To be effective, game rules must focus on requisites to cast the spell, cost in terms of resources, and practical effects. Narrative prose, on the other hand, can add detail and nuance; it can bring spellcasting to life by describing the rush of magic energy surging through the wizard’s veins, the crackling of the air as the spell is prepared, and the feeling of intoxicating satisfaction when the spell is discharged. The rules tell us how the spell is cast and what it does; the fiction helps us imagine what it must feel like to actually do it. That is a feeling that we may experience for the first time through literary representation, but also one that we can summon back later, while we play Frostgrave, enjoying in turn a richer and more nuanced representation.

The same can be said for the brand of magic described in the Ghost Archipelago game. Players of the game identify with the Heritors, who descend from the original explorers who drank from the Crystal Pool, and are for this reason gifted with extraordinary abilities. These abilities share with the spells of the original Frostgrave the fact that to use them a player must roll a die against a given target number. Moreover, we are told that using Heritor abilities exacts a terrible toll called Blood Burn, which causes a point of damage for each successful utilization, and two points of damage for a failed attempt. This rule poses a practical limit on the use of particularly powerful moves, acting as a wise balancing mechanism. We can imagine that a physical reaction called Blood Burn must have quite dramatic effects on the body of the Heritor, but in game terms its application amounts to a simple numerical adjustment. It is game-based fiction, then, that has the best means to supply this important experiential element.

A good example is in the novel Farwander, in which the Heritor Lady Temnos uses an ability that the game calls “Hurl”. The ability is not named in the story, but the representation is accurate enough to allow identification. The description in the game rules, as we can expect, is strictly functional:

This ability can be utilized during a Heritor’s activation. The Heritor may spend an action to pick up a large rock, log, dead body etc., and hurl it at an enemy. The Heritor may make a shooting attack with a maximum range of 8’’. This shooting attack is made with the Heritor’s Shoot stat. If the attack hits, it does +3 damage.

In the novel, both the use of the ability and its cost come across vividly, becoming the centerpiece of an intense sequence in which Lady Temnos rescues the titular character from a giant snake. Comparing the two passages allows us to see how the fiction acts as an emotional and thematic amplification of the original game function. The very length of the fictional rendition is meaningful in this sense:

Somehow, Lady Temnos was on the rocks above the cave entrance [possibly by using the “Leap” ability -91- author’s note]. She was behind the snake’s head, unseen. Blood was wet on her face. She wrapped her arms around a rock almost as big as she was and wrenched it out of place, in a shower of dirt and moss. She took the weight on her back leg and heaved the boulder down off her perch. The rock slammed into the top of the snake’s skull. Its head was driven down into the dirt at Farwander’s feet. Its yellow eyes bulged and bone cracked. … [Farwander] scrambled up the rocks to find her crouched there, gasping from exertion. Her hair was wet with blood and sweat. Farwander squatted beside her and put a hand on her arm. It was hot, as if she was in the grip of a fever.

‘The Blood Burn. The price a Heritor pays.’

Farwander tilted her face upwards. A rivulet of blood trickled from the corner of her eye. More was smeared around her mouth and ear. It had started to clot in her hair.

‘The price?’

Lady Temnos brushed Farwander’s hand away. ‘Power does not come from nowhere,’ she said. ‘Like everything, it has to be paid for. When we use the strength our bloodline gives us, it takes its toll on our bodies. We must pay for our power in pain.’

Mark Latham, in Destiny’s Call, showcases an even larger and more detailed range of abilities through the character of a young Heritor who is just discovering his own talents. Throughout the novel, we see the character pluck a flying arrow straight from the air, fight at supernatural speed, and avoid enemy attacks by magically blending into the background. In each instance, we see what used to be a set of abstract instructions turn into a dynamic and memorable action.

Paraludic fiction can also explore situations that, while thematically compatible with the contents of the storyworld, surpass the limitations imposed by the spatial and temporal scale of the game. It can do so by telling us about journeys that last days or weeks, and can extend over hundreds of miles, while most scenarios in the game will take place in much smaller areas of in-game space, and will consume maybe 20 or 30 minutes of in-game time. Paraludic stories can move past the constraints of the game also when representing events that involve large numbers of characters (like in a naval battle in Farwander), and that would be unbearably cumbersome to handle in a game session of Frostgrave. The horizon of the game can also be expanded without transgression by showing the reality of the stories through the unusual point of view of one of the crew members (as in the novel Farwander), rather than from the perspective of the leaders with whom the players tend to identify.

Along the same lines, the stories can relativize source materials that, due their being introduced as part of a rule manual, are supposed to be treated as holy writ. Good rules are practical tools that leave no room to ambiguity or negotiation. The Heritors for example are described as more powerful than Wardens and bodyguards, and in game terms they can be easily thought of as “superior”. If in a game of Frostgrave a bodyguard defeats a Heritor easily, chances are that the game is being played wrong. Ancillary prose, however, does not have to embrace all of the implications of the source materials, as we see most remarkably in the novel Destiny’s Call. The story opens in a city state in which Heritors are treated as outcasts, and hunted down by squads of specially trained guards. Reduced in poverty, living furtive existences as beggars or thieves, these Heritors still feel the call to the Lost Isles and the Crystal Pool, and must resort to stealth to find a passage on a ship. In a similarly revisionist perspective, the protagonist of The Clockwork Chart is a Heritor who sees his legacy not as a source of pride but as a dreadful curse. The reason this time is not hostility from others, but awareness of the corrupting nature of the Heritors’ power:

I seek the opposite of power … The Crystal Pool’s powers have cursed my family, made its sons and daughters into killers. Not just my family. It has turned honourable lines into dynasties of cruel tyrants, merchant houses into pirate clans, and dissolved whole generations into scatterings of rogues.

Destiny’s Call and The Clockwork Chart introduce situations that are not contemplated in the game manuals, do not feel intuitive to players used to control powerful and proud Heritors, and yet at the same time do not clash with any of the original materials. The stories reveal unexpressed aspects of their theme, and in so doing also make the characters more fallible, human, and relatable. Similarly to what we saw before, the significance of this literary remake is bidirectional, as players who have read the stories can decide to apply the idea of persecuted or morally conflicted Heritors to gameplay. Scenarios can be devised precisely to capture this uncommon yet perfectly compatible perspective. Even a standard scenario that avoids non-canonical elements can be perceived differently if simply the player thinks of her Heritor as a tormented anti-hero. The moves and in-game actions may remain identical, and yet the experience for the player will be altered.

Paraludic fiction in the Frostgrave family also functions to tie together segments of the storyworld that were developed independently. If pulled together and tightly interwoven, these elements solidify the illusion of a single, consistent setting. In our case this process can be challenging because the original Frostgrave and Ghost Archipelago take place in very specific, isolated, and distant locations, leaving it to the players to imagine the physical reality of the land in between. This situation may easily make the game’s bifocal storyworld feel disjointed.

We find a remedy to the physical and conceptual separation of these two settings in the novel Oathgold, published after the release of Ghost Archipelago. The story is set in the frozen wastes of the original game, but it features an episode in which the protagonist finds a vial of water from the fabled Crystal Pool that the Heritors constantly seek. From that passage in Oathgold the player and the reader can form a stronger sense of a unified reality shared by the novel and both game settings. When knowing that objects can travel from one pole of the game to the other, it becomes easier to imagine the space that separates and yet connects the two locations, the time it took for the vial to travel from the seas of the south to the plains of the north, the hardships faced by the people who transported it, and so on.

Latham’s novel Destiny’s Call presents a similar idea by showing a character who lived in Felstad’s region before moving to the seaside areas near the Ghost Archipelago. The novel also resolves the problem that the different brands of magic of the two settings seem to have virtually no connection, with no Sigilist in the south or Earth Warden in the north. It makes sense that this would be the case in the game manuals, since Frostgrave was written without planning for a sequel, and Ghost Archipelago could not have reiterated the magic system of its predecessor without feeling derivative. In terms of worldbuilding, however, that separation must be justified or it will be felt as a flaw. Destiny’s Call states that the branches of magic used in the north (and described in Frostgrave) are known in the south too, but simply not often practiced. The different approaches to magic in the two regions are attributed to immense distance and lack of communication. As a character in the novel narrates:

I had just slain my master, the Thaumaturge, Alam’Vir. He had unearthed a relic of singular power in the ruins of the frozen city that men call “Frostgrave”. That place is a world apart from Yad-Sha’Rib, so far from my humble birthplace that it might as well be upon the moon…. I fled the Frozen City … After a long and arduous journey I returned to my master’s keep, whereupon I used the periapt to take control of all that the old sorcerer had.

Similarly, in Page’s The Clockwork Chart, the protagonist sends a letter to “his disgraced cousin Linnet, a sorceress who spent her days wrestling antiquities from an ancient frozen city people called ‘Frostgrave’. In reply she sent him a long letter about her adventures, plus an ancient leather-bound tome written in a dead language.” This way, the specialization of the two regions is preserved, while possible complaints about the composite nature of the storyworld are prevented.

Frostgrave: The Playable Stories

One final aspect of the porosity between paraludic literature and its gamic sources is in the playable scenarios for Frostgrave that are included at the end of each of the novels. As Gray wrote, “just as paratexts can inflect our interpretations of texts as we enter them, so too can they inflect our re-entry … For texts that destabilize any one media platform as central, each platform serves as a paratext for the others.” Similarly, the game Frostgrave may have given origin to paratexts such as the non-interactive stories we are discussing, but such stories, in turn, can be transported back to the original system and experienced in playable format. This is precisely what happens with the scenarios that are found in the Frostgrave novels, and are based on central episodes from the narrative. By setting up and playing these scenarios, the players can effectively return to the themes and tones of the novels and experience them within a fully ludic framework. First you played the game, then you read a story about the game, then you play a game about the story about the game. Incidentally, if a completist Frostgrave player buys a novel principally to have access to the scenario, does the scenario become the text and the novel the paratext?

It is true in any case that the playable scenarios included in the novels tend to mirror the events of the stories rather loosely. They do not retell episodes from the story in detail, nor do they ask the players to take on the role of the characters of the novel. Rather, the scenarios act as variants that include the same enemies, settings, and general situations, but mold them according to the requirement of the game. Still, the connection of these playable scripts with the novels is strong enough that the reader is advised not to read the scenarios until after finishing the story, in order to avoid spoilers.

To give some examples, the novel Second Chances includes a scenario for Frostgrave called Corpsefire, and borrows its thematic core from an episode in which a group of wraiths breaches a protective circle to attack Yelen’s party. The episode in the novel takes place at night, and opens with Yelen waking up to the realization that she is under attack. The focus of the scene is first on her horror and confusion, and later on her actions. The Corpsefire scenario, on the other hand, includes two parties of adventurers (one controlled by each player), plus a number of wraiths controlled by the game system (and mirroring the wights described in the rules manual). One player’s party is inside the protective circle and controls several treasure tokens. Most of this party’s figures count as asleep at the beginning of the scenario. The other party starts outside the circle, and will attempt to steal some of those treasures. The automatized wraiths, meanwhile, move toward the circle with the intention of breaking it to attack the adventurers. The scenario captures the overall flavor of the narrative source, but follows the original plotline only generally. This is particularly evident in the fact that the scenario aligns itself with the game’s core idea of featuring two opposing warbands controlled by players, plus a number of automatized non-playing characters. Acquisition of treasures, being one of the elements that determine victory in the game, is included in the scenario too, despite the fact that in this part of the novel the characters are concerned only with their own survival.

Similarly, the novel Oathgold contains a scenario in which the players’ crews stumble upon a sacred site and meet the ire of the rangifers who worship the place. Again, in the novel the protagonists are exclusively interested in surviving the encounter, while in the scenario the players must also attempt to recover the treasures that are seen glimmering in a pyre. The same can be said for the scenarios in the novels Farwander and Destiny’s Call: a dramatic fight in the stories; fighting and treasure hunting in the playable variants. The characters in the works of fiction may have different priorities depending on the circumstances, but the fixed victory conditions of the game demand that stable, predictable goals are inscribed in the architecture of every scenario. The overall effect is that, due to different objectives, the playable characters appear greedier and more reckless than their fictional counterparts.

In conclusion, paraludic stories based on Frostgrave and Frostgrave: Ghost Archipelago offer a good example of the richness and complexity of the exchanges that are possible between games and stories, especially in the case of games that are driven by a strong narrative and include a detailed storyworld. Paraludic literature tends to come after the game, and usually after a notable gap, because the game must first show to be successful enough to justify an ancillary publication, and the writers must be given the time to craft their work. Still, the sequence of parent game and narrative progeny does not mandate a unidirectional relationship, and can result in perfectly mutual and egalitarian exchanges. As we saw in our case study, game manuals and self-contained works of fiction can equally contribute to the enrichment of a shared setting. The content of the game manuals obviously defines the status of the fictional world, and in so doing influences the themes and design of the books. The books, in return, add materials that can usually be plugged back into the game, contributing to the evolution of the original storyworld.

Nor is this a redundant process, as the two media involved in this process have strengths and weaknesses that lead them to contribute to the experience from different angles. Game manuals must be clear, unambiguous, and practical. As such, they are effective conveyors of large quantities of units of meaning. A list of twenty spells or a bestiary of sixty monsters in a manual will vastly and efficiently expand the thematic furniture of the storyworld, even if each of those entities is barely sketched (maybe simply by a name, a synthetic description, and a set of stats). While rule manuals mainly expand, paraludic literature excels at deepening. It can add innovative elements to the world, as we saw, but its most valuable and specific contributions come in the form of extra detail, psychological insight, and a larger palette of nuances.

These are not secondary contributions, as they can make gameplay feel more solidly grounded in a fictional reality, and therefore more convincing and compelling. Effective paraludic literature therefore should be seen not as a mere addition to a preexisting product, but as a vital part of the product itself; not a prosthesis but a living, pulsating, and surprisingly active limb. When paraludic literature is in tune with its sources, the synergy that emerges between fiction and game can coalesce into a larger and more immersive fictional world. It’s a world that we can choose to explore through the telescope of the game or the microscope of the fiction, or, even better, by skillfully and playfully alternating between the two.

–

Featured image “Frosty Grave” is by Simon Evans @Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

–

Marco Arnaudo is a Professor at Indiana University, Bloomington, where he teaches about games, comics, military studies, and Italian culture. He is the author of several books, including Storytelling in the Modern Board game (McFarland, 2018). He designed several tabletop games. His most recent game is Four against the Great Old Ones (Ganesha Games, 2020). He reviews board games on his YouTube channel MarcoOmnigamer, which has 21,000+ subscribers. Other interests of his include martial arts, carnivorous plants, and jigsaw puzzles.