Looking at the current market of board games designed by people in Taiwan makes one question the meaning of “Taiwan.” If this name refers to a national boundary and subsequently the cultural creations that represent peoples, experiences, and histories within that boundary, board games have presented a conflicting image of Taiwan, in which appropriated figures of Western empire occupy and dominate most parts while the more organic and original scenes of Taiwan tend to be poorly depicted. Take one of the most iconic and historic board games in Taiwan, Uncle Wang’s Richman, for example. It was released around 1962 by Li Guang Hang (黎光行) and it is still commonly seen in stationary stores in Taiwan nowadays, but the game was almost a direct appropriation of the game Monopoly released 30 years earlier in the U.S. The historical development of board games in Taiwan flourished with games like Uncle Wang’s Richman – ideas and images discernibly adopted from the imperial gaze permeated the “local,” which had yet to share an equal status with the Western empires. I was constantly conflicted when looking at games like Richman published in Taiwan. Many of them seem to me, at the first glance, like an embarrassing attempt to replicate the design of successful Western models. I saw the enthusiastic effort of many people in Taiwan who strive to create “Taiwanese board games,” but as a Taiwanese person and a regular consumer of board games myself, I do not know how to appreciate their work judging from the experience I have had in Western games, leaving me with both a sense of guilt for not being able to admire their effort and a sense of inferiority for the games that I look down upon are the ones that dearly belong to my culture and my homeland. In the midst of frustration and desperation, I started to ask myself: is there a different way to interpret this predicament when the history of Taiwan was predominantly formed in the maneuvers of colonial power? How can I counter the imperial influence when its presence seems to hold dominance in my view?

In the preface to Craig Santos Perez’s poetry collection, From Unincorporated Territory [hacha], he introduces Guåhan’s classification “as an ‘unincorporated, organized territory’ of the United States; the land is considered “unincorporated” because only limited protections are applied even though it is recognized as under U.S. jurisdiction. To take Perez’s introduction as a starting point, I want to propose a theoretical perspective to view board games as an “unincorporated territory” of the knowledge production of the West. Although unincorporated territory initially denotes a strategically ambiguous and thus expendable status of a particular domain, I consider that such deliberate disregard also affords a field to develop, flourish, and confront in a direction that is often unattended by the dominant. As the existing discourse about board games, including the categorization, terminology, and standard of evaluation, was predominantly established by the West, fun has become the primary goal of board game design. However, the utilizing limit of this orientation that involuntarily denies making cultural or political contributions on a noticeable scale also indicates a possibility to go beyond that initial restriction, that is, to reach beyond the tyrannical purpose of “just for fun.” By seeing board games as a vigorous territory in which people in Taiwan actively participate and by recognizing their struggle through the pervasive imperial influences, board games can be, as how Yunte Huang defines the transpacific, “a semiotic space that mediates between national narratives and the ‘authoritative regimes of epistemology’ that enables them.” The seeming triviality of board games entails a resilient textuality in its thematic representation, which can smoothly traverse national boundaries and produce a widely accessible narrative in the gameplay to its audience.

In recent decades, Taiwan along with other East Asian countries have acquired a positive international recognition due to their notable growth in economic performance, but this general recognition, as noted by Janet Hoskins and Viet Thanh Nguyen, did not emphasize Asia’s emancipation from its colonial histories but rather “deploy[s] a language that is predominantly one of commercial expansion and globalization.” Taiwan’s economic and political achievements do not mean that it is exempted from political exclusion or strategic exploitation. The Taiwan Relations Act passed in 1979 as an urgent replacement for the Sino-American Mutual Defense Treaty, which would have expired in 1980, and Taiwan was considered a beneficial alliance in maintaining “peace, security, and stability in the Western Pacific” in the Act. Although the expression of “the absence of diplomatic relations and recognition” with respect to Taiwan is mentioned several times in the Act, there is no guarantee whether the U.S. would or would not intervene militarily, thus arguably situating Taiwan in an ambiguous position conveniently at the United States’ strategic disposal. The reaction to this Act from the people in Taiwan remains relatively positive, but we should not easily overlook the violent histories of imperial influence in the Pacific by forgetting Taiwan’s own precarious state in becoming part of a defense network for the U.S. In this regard, I also consider board games as a humble reminder of Taiwan’s relationship not necessarily with the U.S. but the aggressive entity of Western empires, because many modern board games, whether the visible trace of imperial influence can be clearly identifiable or not, are products designed in a prototypical model that was formed under the imperial gaze. Every game design is a participation in and a reply to that model, infusing a complex mixture of national narratives and individual agency.

Take the Taiwanese game Richman, for example. After the U.S. passed the Mutual Security Acts in 1951, Taiwan received material and financial support from the U.S. based on the premise that Taiwan was held as part of the first island chain in the defense against Communist power, and the intensive interaction with and cultural influence from the U.S. thus prompted the creation of Richman – a game heavily inspired by the Monopoly from the U.S., which was enjoying its commercial success at the time. However, although early editions of Richman shared almost identical rules with the Monopoly, some of the rules had been gradually changed throughout the circulation of the game in Taiwan. One of such cases is that in the original Monopoly, players can establish an estate after the player has acquired all lands of the same color, but in Richman, players can only do so when they step on the exact spots of their lands. How and why the change of this rule occurred remains of intriguing interest. Furthermore, although the game was produced by the same publisher throughout the game’s history of development, there were always more than one edition of the game circulated in the stationery stores, and the geographical and social aspects of Taiwan constantly brought new materials into the game. The earliest and most common example of the game’s thematic redesign was to replace the original American landmarks with cities, streets, or train stations in Taiwan. After Taiwan’s economic boom in the 1980s, purchasing real estate was no longer the only way to earn money and win the game as many other financial instruments, including stocks, bonds, and insurance were introduced to the Richman series. Many later versions of the game have abandoned the original mechanic of Monopoly, that players earn money primarily through buying designated locations and the amount they receive from other players is determined by the number of properties they possess; instead, the game has introduced other win conditions that were mostly unrelated to the theme of “becoming rich,” like collecting “happiness” and “honor” points, collecting the most Taiwanese street food, or establishing a successful restaurant. Comparing to the original Monopoly as a parody of capitalist expansion, Richman has gradually become more of a reflection of the everyday life in Taiwan. The adaptation of Monopoly to Richman shows that the latter has, after the participation of culture and people in Taiwan, been reshaped into a perceptibly different form from its predecessor.

“Amerigames” and “Eurogames”

To understand further how cultural influences from Western empires has affected the development of board games and to see how people in Taiwan negotiate and navigate through these influences, we need to first identify the colonial themes and Eurocentric tendency in Western board games. An unofficial but widespread categorization of board games we have today is the distinction between “Amerigames” and “Eurogames”; the former emphasizes “a highly developed theme …, player to player conflict, and … a moderate to high level of luck,” while the latter “should have easily grasped rules, depend on strategy rather than luck, lack direct confrontation and require collaboration for progression.” The distinction was made visible primarily due to the Spiel des Jahres award established in 1978 by a group of German game reviewers; nominees were and are still limited to games that have been released in German-speaking countries, and this annual award has arguably become the most prominent event in the board game industry ever since. From a historical perspective, the field of board games is dominated by an intense national hegemony, and players are constantly reminded of the sovereignty that Western empires have over the discourse of board game by complying to these categorizing criteria. Despite the blatant display of a tyrannical standard, board game players and designers in Taiwan largely remain loyal to this concept of categorizing and evaluating games, struggling to participate in a nationally limited discourse that represents an international success. In 1982, inventor and game designer Ying-Zhen Chang (張營鎮) released the game Tiandi Cards (天地牌). The game’s design shared a similar appearance to playing cards but with ingenious tweaks to expand both its playability and practical utility. The “Jack,” “Queen,” and “King” in playing cards were replaced with “Bao Gong the Rightness,” “Kongming the Omnipotent,” and “Guan Yu the Cast-iron” in order to represent R.O.C.—the Republic of China that is Taiwan. Not only could the Tiandi Cards be used to played games that are available to playing cards, according to Chang, it could also be used to calculate perpetual calendar and perform traditional Chinese fortune-telling. Although Chang patented Tiandi Cards in Taiwan and attempted to do the same in the U.S. with the ambition to promote the game on an international level, his plan did not succeed eventually due to the lack of financial support from and commercial relationship with larger companies. The aspiration to create the “Asian playing cards” thus fell into obscurity, as the discourse of board games was guarded not only by a national boundary but also by a demanding standard of economic competence, the capability of which people in Taiwan has yet to possess at that time.

However, what truly separated Eurogames from the rest was the demonstration of imperial power through colonial themes and iterations of a Eurocentric history. French historian and board game designer Bruno Faidutti was, perhaps, the first to observe and write about the issue of colonist themes in Eurogames. Inspired by Edward Said’s Orientalism, he notices the absence of natives and their euphemistic or outright racist reappearance in games where the relationship of colonizers and the colonized are heavily implied but the signification of each role is left in ambiguity. Colonial themes in Eurogames are commonly used in grander productions which correspond to the significance of such a narrative, and these games would sometimes straightforwardly adopt the name of the once colonized land. Puerto Rico is a classic game that embodies both the colonial theme and the deliberate erasure of colonial violence. The land of Puerto Rico was a Spanish colony from around 1493 to 1898, and the game was essentially a reenactment of this history; in the game, players can “place plantations and build buildings … produce goods and then sell or ship them” with the help of “settlers,” who are in fact Indigenous slaves under the given historical context. Although there are minor debates about the use of colonial themes in Eurogames, this popular narrative mostly remains uncontested and unproblematized. The colonialist tendency in Eurogames is so prominent that Mandarin translations of Eurogames tend to follow this trend even when the game’s original name has no such semantic indication. The problem of repeating a colonialist narrative is more complex than a simple demonstration or reiteration of the imperial power, because very often, the colonial narratives were not constructed directly from original colonizers but from a sphere of countries that acknowledge the propriety of colonial histories, thus forming an intricate network in which the violent histories of colonization were carefully preserved and embellished in what Johan Huizinga calls the “magic circle” – a playground where an absolute and supreme order reigns. The game Puerto Rico was designed by German game designer Andreas Seyfarth, and although Puerto Rico was never part of German colony, the land remains an unincorporated territory under U.S. rule to this day. As a result, to counter the hegemonic image production from Western board games is also a crucial attempt to resist an imperialist framework.

Existing responses from the West to cope with the implied racism in colonial-themed Eurogames are often inattentive. Most games follow a euphemistic strategy by replacing the original theme or labels of game components with a new one without addressing the issue. Such an example of changing labels can be seen in Puerto Rico itself, which replaces the original component title of “colonist” with “noble.”

Board Games in Taiwan

To explore how a counter-hegemonic discourse may operate, I want to bring our focus back to Taiwan and identify some possibilities and changes that are already in development. By doing so, I am not trying to establish a new category of board games that relies on a national boundary like “Taiwanese games.” As Tracey Banivanua Mar observes from the decolonization movements of Indigenous peoples in the Pacific in the 1960s and 1970s, efforts to stand against imperialism and to promote decolonization could “emerge as an identity, a belief system and a thought process that practised independence,” and movements of decolonization that insist upon the recognition on a level of nation state may easily become, as many critics of neo-imperialism have argued, “a form of imperialism through retreat rather than invasion.” To theorize movements of decolonization and anti-imperialism, I would like to, following Banivanua Mar’s observation, “refocus on people rather than territory, as agents of decolonization.” As I have mentioned how the “magic circle” in games easily becomes the preserving site for histories of colonization and embellishes the discrimination within an imperialist framework, the shift of focus from a formalizing boundary to the way people actively engage in a cultural form is an attempt to “consider the game as a contextual, meaning-making process” and to break away from a structural perspective that immobilizes the dynamic individual agency by which meanings are created and contributed.

If “play for fun” is considered the fundamental standard of board games established by the West, the idea of “seminar game” from a game publisher in Taiwan, Taqun Workshop (他群), directly goes against the tyrannical principle of “fun.” According to Taqun Workshop, seminar game is a category of board games in which the discussion of various social issues, including wealth inequality, class mobility, deliberative democracy, and functions of an impartial judicial system, is brought in as the main focus of a game so as to “resonate with players’ experience in reality and generate a unique gameplay for each individual.” For example, in Game of Utopia, players respectively represent the people within a specific social class and they are given abilities that can influence different aspects of the game, like the rules adopted, the number of cards drawn, or the duration of the game. These “roles” that represent people from different social status are designed to be unbalanced in terms of their probability to “win” a game, because players are expected to create their own balance through the interactions in the game as their represented roles. Therefore, in the process of playing Game of Utopia, the game itself becomes a symbolization of society, in which both the goals of different social class and the social ideals of each player are put into action. In a way, Game of Utopia is not really a “game” anymore but an active discussion, with the game being merely a platform where the communication is carried out. In their concept of “seminar game,” Taqun Workshop’s deliberate deviation away from “fun,” as recognized by Bonnie Ruberg, opens up a new field of possibilities that allows game designers “to challenge assumptions about what games can and should do.” If we identify the overbearing standard of “fun” in games as the imperceptible political strategy that caters to imperial conquest, the “un-fun” connotes an intention of decolonization to counter the imperial narrative. The idea of seminar game no longer creates an isolated world of magic circle “dedicated to the performance of an act apart,” but instead its rules and boundaries function crucially within a mutual understanding of social context, thus returning a large portion of individual autonomy to each player. The goal of the game is not to win or to have fun but to reflect diversity, foster tolerance, and invite discussions.

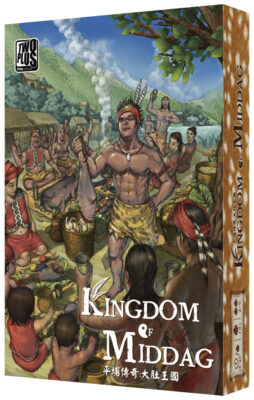

To give another example of stepping outside of imperial narrative, Kingdom of Middag designed by Taiwanese game designer Jog Kung, can be seen as a manifestation of board games’ diversifying textuality. The name “Middag” refers to the leader of the Papora tribe (巴布拉族), who had ruled a large part of the land from Changhua to Hsinchu and Taoyuan before the arrival of Ming loyalist Koxinga in 1651. Since the source material that the game is based upon is very limited due to the fact that the Papora tribe did not develop a writing system and existing historical documents about them were mostly found fragmentarily in the journals left by The Dutch East India Company, the game acts more like a spiritual successor of this part of history. Jog Kung’s deliberate choice of this source material seems to be a creative attempt to reimagine a part of Taiwan’s past that is no longer accessible. As the game participated in Spiel des Jahres in 2019, Jog Kung has demonstrated that following the grand concept of Eurogames does not necessarily entail the adoption of a Eurocentric historical perspective. By bringing in a more remote historical and cultural scope into the existing themes of games, we may begin to speculate on the possibilities in future games in which Indigenous people may become the primary roles embodied and empathized by the players. Nonetheless, these efforts are far from enough. As critic, educator, and director Anita Wen-Shin Chang criticizes the narrative of the film Fishing Luck from “a Han viewing position” and its problematic use of “humanism as a strategy to engender empathy,” I share a similar concern and aspiration in a sense that I also want to know how an Indigenous game designer would “resignify the codes of primitivism in translating their story” onto the game board, because “there always exists the danger of mis-representation or underrepresentation” in both cinematic language and board game narratives.

Conclusion

To reflect on my initial frustration from looking at the development of board games in Taiwan, I want to call back to the definitive text that first outlined transpacific studies. In “Our Sea of Islands,” I found that Epeli Hauʻofa suffered a similar sentiment to my frustration when he told his students in the University of the South Pacific about the Western view on the people in the Pacific, that they were considered as insignificant microstates depending constantly on migration, foreign aid, and bureaucracy without any economic productivity. To reach beyond the active belittlement of the Pacific Island states actively promulgated in “views held by those in dominant positions about their subordinates,” Hauʻofa maintains that there is a need to “focus on what ordinary people are actually doing, rather than on what they should be doing” so that we can see a broader picture of reality. Therefore, my goal is not to provide an evaluation that determines whether board games in Taiwan succeed or fail in resisting the prevailing imperial narrative, and instead, I seek to provisionally recognize the effort of those who confront Taiwan’s colonial histories and challenge the imperial influence. The significance of such recognition lies in the fact that the act of decolonization is not a fixed procedure with a definitive end but a persistent endeavor that requires constant attendance. As the influence of imperialism heavily relies on preexisting boundaries that are cautiously maintained on a national or governmental level, we need to adopt a countering point of view that allows the complex and dynamic autonomy of the people to be adequately identified, so that an epistemological space different from that of the predominant structure can be created. For me, there are more to be told in a game through its dynamic interaction between players from different families, social classes, and ethnicities. Although each individual seems to have been put into these societal and national categories that preordain their characters and values on a certain extent, the way people interact with or struggle through these categories creates multiple subversive points where operations against the formalistic boundaries potentially flourish. As a passionate board game player born in Taiwan, I long for more board games in which the element of fun ceases to hold a superior position, and I yearn to see more games that embody the inclusivity and boundlessness of the ocean surrounding this island.

–

Featured image from Piqsels: https://www.piqsels.com/en/public-domain-photo-fyfvm#google_vignette. Public Domain.

–

Aria Chen is a graduate student in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures at National Taiwan University. He started playing board games since senior high school and was planning to become an English teacher utilizing board games as teaching material for intermediate students, but due to realizing the practical limits in the field of teaching, he turned to literary studies.