The relationship between digital and non-digital gameplay experiences is still quite an undeveloped topic in Game Studies literature. These two different gameplay experiences have been influencing one another for decades with various and sometimes surprising results. An example of this contamination is Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, a mixed digital and tabletop game in which a group of players must collaborate in order to disarm a bomb. The game has a digital interface which represents on the computer screen a stereotypical Hollywood movie bomb full of colored wires and adorned with a menacing red timer. The players can collaborate to solve the puzzle online by using a videoconference software, but the developers explicitly encourage the players to print the instruction manuals and meet physically to enjoy a more immersive experience. Another interesting example is represented by the case of games which cross their original medium: on one hand popular videogames, like Dark Souls or Darkest Dungeon are adapted into tabletop games which try to evoke the atmosphere and the gameplay experience of the original material; on the other several tabletop games, like Gloomhaven or Root are ported in a digital versions which sport the same rules as the source material. In this this paper I try to deepen our understanding regarding how players perceive and interact with these cross-media contaminations. More specifically, I investigate whether the player’s experience changes when the same game is played via software or its tabletop version. The empirical research is an explorative study which focuses on players who tried both the tabletop and digital versions of the card game Magic: The Gathering (MTG). The game was invented in 1993 by Math PhD student Richard Garfield and was originally meant to be played by two persons, each using a deck of 60 cards which usually depict fantasy themed characters, actions and locations. These decks are created (or “built” in the game terminology) by players from a pool of more than 20,000 cards according to their strategic and or thematic preferences. The fantasy setting should not fool the observer; what the game is really about is creating intricate mathematical combinations of synergistic effects in order to maximize the chances of defeating the opponent. This is particularly evident in the so called “combo decks” which are based on creating card combinations able to exploit loopholes in the game rules in order to (theoretically) generate infinite amount of resources or deal infinite points of damage to the opponent and instantly win the match. The complexity of the game is so high that it become a popular topic in artificial intelligence research, and it was even demonstrated that a MTG match can become a Turing complete system. The game can be played in its original tabletop version but also through various official and unofficial software. It is even possible to play it in a hybrid environment in which players meet online and use their webcams to show their table and physical cards. In this research I interviewed players who personally experienced MTG through more than one different version of the game. Their stories suggest that the tabletop version of the game seems to be more immersive, while the onilne version is more comfortable and more accessible, especially for new players. However, when playing the online version of MTG, players seem to exhibit lower levels of empathy towards their peers.

Enjoyment and Player Experience

It is a generally agreed upon hypothesis that one of the main outcomes of playful activities is “enjoyment.” Sweetser and Wyeth maintain that it is “the single most important goal in games.” However, determining what exactly “enjoyment” means is a more difficult issue. Several studies tackle the problem by creating a division between hedonic and eudemonic experience. While the first, usually described as “enjoyment,” is associated with short-spanned feelings of pleasure and excitement, the second is associated with the achievement of a deeper level of reflection and more enduring sensations. For example, Cole and Gillies research on eudemonic experiences shows how functional challenges tied to the game rules and emotional elicitation create different senses of appreciation in the player. This broader concept of positive appreciation partially overlaps with the idea of flow.

The concept of flow was introduced by Csikszentmihalyi, and it is defined as:

“A state or a sensation that occurs when someone is participating in an activity for its own sake. […] The characteristics of such intrinsically rewarding flow experiences are intense involvement, clarity of goals and feedback, concentrating and focusing, lack of self-consciousness, distorted sense of time, balance between the challenge and the skills required to meet it, and finally, the feeling of full control over the activity.”

Like media appreciation, flow can be divided in some subdimensions: Rheinberg et al. distinguish between “automatic running” and “absorption.” The first refers to a high level of mastery obtained over the activity: the feeling of complete concentration, the sensation of being in control, and the achievement of smooth and automatic reasoning. The second factor refers to the feeling of complete involvement in the activity and it is accompanied by a distorted perception of time and absent-mindedness.

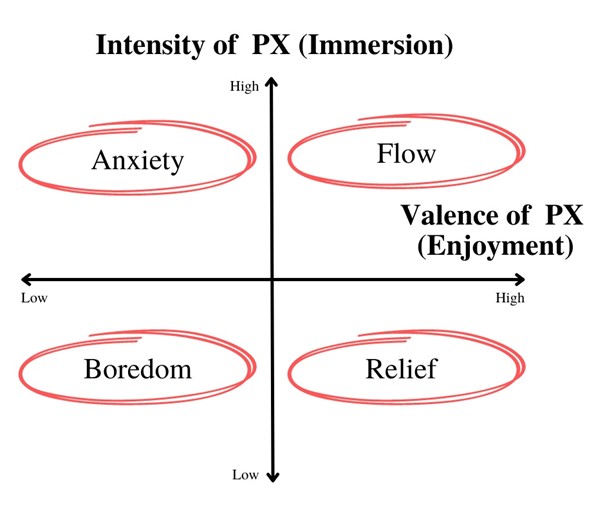

Despite the wealth of related research, the relationship between enjoyment/appreciation and flow remains an open debate. Some researchers maintain that the concept of flow is narrow, and it should only be related to extreme experiences, thus excluding situations in which games are enjoyed as an occasional pastime. Others instead maintain that the two concepts are completely overlapping. Mekler et al. try to disentangle the issue by proposing an encompassing framework which may help in analyzing not only flow and enjoyment but the whole player experience (or PX). This framework conceptualizes PX across two main dimensions: intensity and valence. Valence indicates the experiencing of enjoyment during gameplay and, more generally, a positive response of the player towards the game. On the other hand, intensity indicates the engagement of players in game activity, the amount of players’ attention which is absorbed by gameplay’s challenges and environment. This second dimension refers mainly at the idea of “telepresence” (or simply “presence”), a popular concept in media studies which refers to the subjective feeling of being present in the mediated environment rather than in the immediate physical environment. The concept has mainly been used in the analysis of digital games but can be also employed in the analysis of tabletop ones. A scheme of the complete framework can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Valence and intensity of PX framework.

However, this framework has been developed only referring to digital games and without taking into account the context in which the game is played. The aim of this research is, following the example of Litherland, to analyze the quality of the player experience (or as the author defines it, “ludosity”) while accounting for a range of factors: the emotions of the players; the agents involved (which, according to Giddings, are both human and non-human since the different software of physical game pieces influence the outcome of the final game event); the institutions like the rules of the game or the framing of game context which indicates the process (often implicit) in which the participants negotiate a shared understanding and conventions in interpreting said rules; and lastly the contexts which may refer to the physical medium in which the game in played (digital, tabletop or hybrid).

This paper aims to expand the scope of the Mekler et al. framework and to explore the rapidly changing relationship between digital and non-digital games. In other words:

Q1) Does the player’s experience change when the same game is played through its digital or analog version?

Q2) How do these two different kinds of experience influence the intensity and the valence of the player experience?

Methods

This exploratory research focuses on the card game MTG. This choice is motivated by few reasons, the most important of which is represented by the fact that the game can be played both online or offline, and that most players tend to try both experiences. Another reason is the social relevance of the case: the game has been played for almost thirty years and it is still widely popular. The popularity of the game may allow other researchers to easily organize a similar study in order to verify the results of the current paper or to expand its scope.

The data were collected through semi-structured qualitative interviews with players who were contacted on three Italian MTG-related Facebook groups. As suggested by Cole and Gillies, this method was favored over the observation of actual gameplay moments since interviews based on memories of play allow the respondents to reflect on their experience. It allows researchers to gain useful insight which could be lost if players are approached when they are still concentrated on the match. The invitation post explicitly stated that the participants needed to be experienced with at least one online version of MTG, the tabletop game and, if possible, Spelltable, the hybrid webcam system. The possible respondents who commented the posts were privately contacted via Messenger and thirteen of them volunteered for the interview. To guarantee the anonymity of the participants they are quoted as “R1-13” in the paper and every reference they made regarding real places or persons have been anonymized. The respondents are all Italians who identify as male and are between the ages of twenty and forty-five years old. The choice of interviewing Italian players was again due to the relevance of the case: it is esteemed that Italy is one of the countries in which Magic Arena (the official software for playing MTG online) is most played. However, the lack of interviews with players who identify themselves as female or non-binary is one of the major drawbacks of this study which could be hopefully addressed by further research.

The interviews lasted between fifteen and forty-five minutes and they were performed and recorded online due to COVID-19 restrictions and physical distance between the respondents and the researcher. The interviews were structured around five fixed questions, each accompanied by one or two follow-up questions to be used when the respondent tended to dismiss too rapidly the topic of the main question. The early interviews opened with the generic question “What do you like best about Magic: The Gathering? Which are the first things that come to your mind when you think about it?” in order establish a rapport and start the conversation. The other questions covered specific aspects of the game and invited the respondents to make comparisons between their online and offline experience. The interviews were analyzed employing an open coding system which took in account the scheme shown in Figure 1 and a comparison of the experiences of the players in playing the digital and tabletop versions of the game. The list of codes is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Codes for interview analysis.

| Code name | Number of appearances |

| Anxiety | 29 |

| Boredom | 36 |

| Eudamonic Media Experience | 22 |

| Flow – Absorption | 76 |

| Flow – Automatic Running | 33 |

| Frame – Game Context | 95 |

| Frame – Out of the Game Context | 55 |

| Frustration | 57 |

| Hedonic Media Experience | 13 |

| Offline Context | 66 |

| Online Context | 117 |

| Online/Offline comparison | 53 |

| Relief | 41 |

Analysis

Low intensity – low valence

This quadrant of the framework defines a situation in which both intensity and valence of PX are low, and it is associated with feeling boredom. Using as parameter the previously stated idea from Sweetser and Wyeth that enjoyment is the ultimate goal of games, it may be considered the worst possible outcome for a game since it means that the player is neither enjoying nor involved in the game. The analysis of interviews shows that online and offline MTG create boredom in different ways, each resonant with what the players perceive as the specific limitations of both formats.

In the online setting, boredom is tied with the risk of repetitiveness of the game. The digital nature of the game facilitates and speeds up the preparation of a match by taking care of mechanical tasks like shuffling cards and matching in less than a minute; this encourages users to play several short matches instead of few long ones and it leads players to become tired of the deck they are playing way faster:

“I may find a good deck, I play with it and at the beginning it is fun, but then, since the combinations and the playstyle are always the same, it starts to bore me, and I try to build another one.” (R8)

The situation is worsened by the fact that, compared to the offline game, players have more resources to build their decks and more information regarding which combinations of cards are the most powerful. This create what players call “META” or “Metagame”; this acronym refers to the acronym “Most Effective Tactics Available” and it indicates a set of decks, card combinations and strategies which are perceived by the community as the most powerful available at the moment. This set often does not include a lot of possible strategies and a player who wants to adhere to the dictates of the current meta can rapidly become bored:

“It become easily repetitive, because if you do not have a personal interaction and you are always playing the same deck against the same other decks. Especially in a closed META, all the matches become the same thing. Therefore, you end up being bored way before.” (R4)

The META is also present in the offline game, but, due to difficulties in obtaining all the cards for a completely optimized deck, there is more room for variation, and it is perceived as a less limiting structure. However, the surplus of information and resources provided in the online format is also the solution to the problem it generates in that the software offers an enormous variance of situations and formats for playing the game, often allowing players to find another interesting activity when they are tired of the previous one:

“I really appreciate the variety offered by Arena. You can play «brawl», which is a format I discovered on Arena, and I am enjoying a lot. […] Then, if you have the in-game money to spend, you can also play «sealed» and «draft»” (R5)

“In paper Magic I know well what to expect and therefore I am more relaxed. Instead in Cockatrice I always wonder what they will bring if they have built a new deck. If they, did it, it is like a mystery, since I do not know which cards they chose.” (R11)

On the other hand, in the tabletop environment, boredom happens when a player perceives that he is not really participating in the game:

“Boredom can arrive in all the contexts. However, I believe it happens a bit less on Arena since the game gives time limits for the turns and you cannot exceed them. It is also more difficult to be bored because you can always leave a bad game and start another one” (R1)

“It may happen that we are doing a match in four and I do not draw land cards for 5 turns, however I cannot stop the game for the other 3 guys just because I did not draw lands. Therefore, I get bored.” (R9)

The first quotation shows how the online game prevents players from taking too much time during their turns, thus creating a situation in which no one has the sensation of “doing nothing” for too long. More importantly, both quotations show how online players can always leave boring situations without facing sanctions from their peers, and therefore it is more difficult for them being struck in an underwhelming match.

High intensity – low valence

The upper-left quadrant of the framework represents a situation in which a player is fully involved in the game, but at the same time is not able to enjoy the experience, due to issues like anxiety or frustration. The attitude of the interviewees towards anxiety is particularly ambiguous. Some of them identify it as a completely negative experience, either in an online or offline situation:

“One can also try to stress the opponent. As in the paper game there the opponents that stress you, the ones who willingly try to agitate and pressure you, the same thing could also happen in a digital chat” (R9)

Other players instead link anxiety to the crucial moments of a match in which they discover if they will win or lose, and the tension is at the highest peak. These players may not enjoy the exact moment in which they are anxious, but this accumulation of tension is considered an important part of the game.

“I am incredibly anxious all the time, but only when I am close to victory. When I am losing, I am ok and relaxed, and it is difficult that I get agitated” (R11)

“Interviewer: «Is this in a sense a positive anxiety? »

R12: «Well, it is not like I am eating my nails. »

R11: «If it were completely negative, I would not play this game. »” (R11; R12)

Anxiety therefore may be seen as important component of a match, since the accumulation of tension makes more pleasurable its final release at the end of the experience. Regardless of the fact that this sensation may be positive or negative, it seems that the experience of the interviewees’ anxiety is not very much influenced by the online/offline context, but rather by the chance of encountering a toxic opponent (as expressed before by R9) or by the stakes of the game:

“I never feel anxious because I do not play competitively, I do not attend tournaments and if I do, they are of the lowest grade. Once I tried to play in the “Arena Open”, the one that costs a lot of the in-game money. In that situation I was a little anxious since I had the sensation, I was wasting my resources, and therefore I never tried it again.” (R1).

“Interviewer: «When do you feel anxious when you are playing Magic? »

R9: «It depends on which are the stakes. If I am with my friends, I would not say I am anxious […] There is not a “rank” in that situation, do you understand. » (R9)

Anxiety seems to arise in equal measure both online and offline when players perceive the match as important. In an offline context playing with friends creates a more relaxed situation, while participating in a tournament creates in the player the pressure to recover financially from the cost of the enrollment. The same experience happens in an online software like Magic Arena, whose structure emphasizes a sense of competition, since winning matches means obtaining the resources needed to expand your collection. This is absent in other ones like Cockatrice where obtaining new cards is completely free. In situations in which winning matches becomes more important a different factor becomes salient: frustration.

“The frustration is there because when you are playing one vs one you are trying to win. The defeats or, even worse than the defeats, the moments in which you feel you cannot react in any way, are more frustrating because you feel you have an objective, and you cannot reach it.” (R4)

Contrary to anxiety, frustration is always described as negative state of mind. MTG players seems to be especially frustrated when something is preventing them from playing the game in an optimal way. This may happen due to contextual issues or game related issues. The first type happens especially during webcam play where the creation of the setup is particularly clunky, and the higher number of devices needed to play properly increment the chances of problems:

“It is very difficult to understand certain game situations […], because you have to watch on a small screen 4 different tables with cards which are not optimally focused. The communications are also influenced by the internet connection of every player and therefore by mere hardware motivations.” (R1)

The other main frustrating situation is given by the sensation of being powerless during a match. MTG is a game based on the rapid and continuous interaction between the players; when one is no longer able to “respond” to the opponent’s actions, the latter can implement their strategy undisturbed. This situation has several nicknames, depending on which element of the game caused the lack of “answers”, and they invariantly indicate a position of disadvantage.

“In this situation may happen a small exchange of lines, mainly complains, and then you say: «Ok, I cannot do anything about it.» There is a bit of frustration tied to the fact that you do not have options.” (R4)

Some players create decks with the explicit aim to prevent and suppress the opponent’s agency. These decks are nicknamed and “stasis” or “prison” decks, and the players who employ them are often stigmatized. The physical presence of peers who can enforce this stigma may restrain a player from using this kind of deck, but in an online context it is more difficult to incur such sanctions. Players justify this behavior with the lack of interaction and intimacy with the opponents. If a player would probably never play again against a specific opponent, said opponent will never have the chance to enact a revenge for the miserable experience they had to endure.

“Some things are well-known, but when you are playing online there is no policing, no repercussions. Therefore, you can play the most negatively perceived deck, but you are just playing against strangers found online only for that match. (R4)

The comparatively more frequent occurrence of frustration led some players to avoid getting too involved into the online game. Accumulating experience, they learn when continue playing means only getting angry it is time to take a forced break.

“On Arena, especially at the beginning when I used to play much more, there were moments in which I really felt the stress rise and I used to get really mad because I was losing, because I was always playing against the same decks, because my deck did not work. […] In the last years however, I got calmer, and I can really perceive that moment. When I sense that I am getting tired I quit.” (R5)

The frequency of frustration episodes leads a sizeable part of interviewees to believe that MTG software is better off without chat options as they would to be used mainly for slurs.

“I am in a couple of MTG Facebook groups, I believe that if Arena had a chat, it would be only insults.” (R9)

“It depends, in some contexts it is better having a chat but in most situations it is actually better not having it. On Heartstone for example […] it was really harsh. The usual thing was that people wrote you in chat after the match and started insulting you heavily. I admit I also did it on some occasions.” (R11)

Some players also ascribe the increased frustration to the online game itself. They believe instinctively, but without empiric proofs, that when they are holding the cards in their hands the game is fair: everyone has seen them shuffle the deck in order to assure a randomization of the cards. On the contrary, when they are online, they do not actually know what the algorithms are doing, and this creates the suspicion that someone may be favored by the game. This is consistent with what Litherland found in the case of the arcade games: the functioning of the machine is hidden and even mysterious, and this can spawn any sort of legend and myth regarding what regulates it.

“The frustration is even increased by the fact that you do not understand the machine and therefore, since you do not know according to which mechanisms it works, either you believe it is exceedingly stupid or you have that conspirator sensations. Especially when you keep losing and you think: <it is the sixth game in a row that I am flooding, is it possible for this algorithm to function decently?>. […] On the other hand, with the paper game you can sometimes blame the deck, but at the end of the day it you who are shuffling it, therefore there is no one else to blame.” (R6)

Low intensity – high valence

In this quadrant of the Mekler et al. framework we consider a situation in which the player is enjoying the game but does not feel completely involved in what they are doing; the authors describe this occurrence as “relief.” In this situation what makes the difference between offline and online context is the higher accessibility of the latter. The software takes care of all the preliminary steps (associate two players, shuffling decks, …) and applies automatically all the proper rules when cards are played. This allows players to get in the match faster and without continuous effort to keep track of all the reactions triggered by their actions.

“It is very easy, very simplified. If you want to do a match on Arena you build the deck and then you are ready to go. It is very comfy, the fact that it lacks the physical component is comfortable from a certain point of view: you do not need to sleeve your cards, fetch a playmat, keep your table orderly. […] I really enjoy the immediateness.” (R11)

This automation of several processes is also noted have a beneficial effect in learning the rules of the game. Neophytes learn faster how to master the impressive number of rules and experienced players have an easy way to get confident with the new rules which are regularly added with the release of new expansions.

“The biggest difference between Arena and paper Magic is that there is less chance of error in Arena. All the phases of the turn are automated, and this is really an enormous thing. It gives an entry level to an inexperienced player who does not understand these things. They are quite clunky to learn, but once you get more expert, they are exactly the things on which you base your game. […] Arena really helps in learning these things, therefore if I am a neophyte and I start playing, I am immediately starting to assimilate that there is an order of phases to follow for both players.” (R6)

This immediateness makes the game rather than a “full time-hobby,” a pastime which players use to entertain themselves discontinuously, with peaks of gaming when they are particularly inspired, or in bits of free time when they are bored.

“There are times in which I play Arena distractedly, only to kill time. Maybe I am smoking a cigarette after the coffee, I have to get back to study and I the meanwhile I do a match on Arena. It is ok if in this situation I am a bit distracted; I just do things and I do not think a lot about them.” (R9)

This casual approach to the game is made possible because players do not meet physically and therefore there are less penalties for abandoning halfway a boring or excessively long match; moreover, since they do not know their opponents, they also feel less guilty about ending abruptly the match.

“It is not a problem if you play against a boring deck. […] If you are playing for killing the time and you that the opponent has a boring deck you just quit and you do another match against someone else” (R1)

For players with this approach the fast duration of matches and the timer which prevents from taking exceedingly long turns are not a matter of anxiety, but they are traits which actually help insert one or two games in their bits of free time.

“I believe that online the timers are absolutely necessary. […] I sometimes even believe they are too long, not everyone can stay 10 minutes waiting the opponent to do their move.” (R9)

However, the simplification of the experience and the reduced interaction with the opponents have also negative effects on player experience. On one hand they allow a more immediate experience, but on the other some players consider the online game inherently inferior to the paper version. Some players explicitly explain that they are willing to spend hundreds of euros for the paper game, but at the same time they keep playing online just as long as they do not spend any money in it:

“My use of Arena is tied to the dogma «Zero Euros», which one of the things I like in Arena. I understand that there are various level of fruition and if you want to spend all your wage in it you can, but if you want to play casually you can build decks with the cards the game freely gives you. It takes a little more time since you have to accumulate in-game money. […] I do not like this grinding aspect, but if I decide to spend real money I prefer going to the shop and buying real cards.” (R12)

Another example of this underestimation of the online game is the fact that even if players enjoy the game, they tend to remember less the matches they won and to celebrate their successes less intensely.

“I remember a lot of matches played in person and very few ones played on Arena. […] I remember more the ones in person because in person in some way it is different. It never happened to me that I won a match on Arena and then I started making a scene, screaming and so on. In person it happened.” (R9)

Several players report that a barrier to complete involvement in the game is the lower engagement with the opponent. This hinders the creation of a shared frame of “game context” and friendship-making.

“If I go a tournament here in [town where the respondent lives], I meet people I did not know before and it often happens that we organize to play again together. […] Online there is not this necessity, […], most of the times you do not even care who is your opponent, you are just there for the experience of the match. I do not have the same desire to create a group of friends to play with.” (R4)

“I like paper Magic best because I like playing with someone and chat[ting] before, during and after the match. […] I play Arena in the free time mainly because a game can last few minutes and therefore, I can join a game and if another errand arises, I can instantly quit.” (R1)

Flow

Flow in Merkler’s et al. scheme describes the optimal state of player experience. It means that a player is not only enjoying himself, but it also fully involved in the activity. In this part of the paper, I will analyze separately the two aspects of flow proposed by Rheinberg et al.: automatic running and absorption.

Automatic running is an element central to the experience of MTG both online and offline. Even if the game can be played competitively, its complexity requires a substantive amount of concentration and focus from the player. Like Chess, the rules of the game can be learned easily but they are particularly challenging to master. Even when players experience the game as a simple pastime (as it is shown in the previous paragraph), they are employing a carefully built skillset. The players tend to see with pride their capacity of tackling this complexity and perceiving the small nuances of game situations:

“Magic is not like «Candy Crush», it is not a game for a casual player. There are obviously some intermediate steps between a casual player of magic and an obsessed psychotic, but in any case, it requires some effort. You have to know and remember the rules which are not easy.” (R8)

This aspect of the game could be linked to the concept of appreciation proposed by Vorderer and Ritterfed[25] which argue that while enjoyment is linked to immediate responses of pleasure, the appreciation of a game derives by achievement of deeper objectives like decisional autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

The “automatic running” aspect of flow tends to emerge more often when a player is experiencing the competitive side of the game:

“You enter in the mindset «Cut the crap». […] Obviously if someone makes a joke is ok, I have never played in a tournament in which no one ever speaks a word, but make no mistake, you are 100% concentrated on the match” (R4)

“What I also like in Magic is trying to optimize my game lines in order to maximize my chances of victory. […] There is also the variance of the cards and I like the aspect the adapting to these random conditions of variance and playing in the best way possible adapting to the situation.” (R11)

Whereas gaming online for some players means only a discontinuous pastime, for others it creates an environment where they can keep honing their skill with equally motivated adversaries. The “Ranking system” built into the official software of Magic Arena creates a worldwide ladder of players, divided in several tiers. Due to the hierarchic nature of this system, the highest tiers are populated only by competitive players, while the lowest by casual gamers and the ones who are still struggling in their climb to the top.

“The ranked system is the one played by people who want to reach high levels. I am sure that half of the people I meet are doing something very structured. The other half are just people who want to test their new deck or to kill some time. Half of the players are living in a system which I always avoided in the paper games: the competitive one.” (R8)

However, while online winning becomes a more powerful drive, players also observe that in this situation they also feel way less empathic towards their opponents:

“In Arena I believe I feel more pleasure in torturing my opponent. When someone misses the <land drop[26]>, I smile, do you understand? I am happy.” (R9).

“If they upload Commander[27] on Arena it would be way more violent that the paper one. This would happen because it is way easier to find powerful cards and there would be no rules of humanity. You only care about finishing the game, you want to win when you are playing on the computer.” (R4)

The last main difference between online and offline competitive play is again the lack of physicality. Some players lament the loss a fundamental part of the tensest matches: the chance to read the opponent’s body language. Like in Poker, being able to read expressions or tics of opponents may prevent a tragic defeat:

“You really enter in the Chess-like part of Magic when you are playing against an opponent and just against a deck. It becomes important watching the face of the other, how they are playing, how they answer to your bluffs; you are playing on more levels while on Arena you have tighter space. You still can bluff, there is still the space to play against the opponent and not just against his deck, but it is very limited. The only feedback you have are the response times of the other, if I play and he answers rapidly I think something, if he takes more time, I can deduce something else, but he may be doing it on purpose.” (R6)

It is interesting to note that the respondent in this case is completely identifying the opponent with its presence in the online world: the deck of cards. Once again it is shown how playing online the level of empathy drops significantly opponent, playing in some unknown location around the world, is considered somehow less that a real person.

Contrary to automatic running, which is a concept more related to the control over the course of the game, absorption represents the part of the concept of flow tied with the sensation of complete involvement into an activity. The narrations of interviewed players tend to emphasize the idea that offline Magic is almost always more immersive than the online version. This gap between the two version of the same game originates from two main aspect of MTG which are difficult to simulate in a digital environment: the company of other players, especially if they are friends, and the complex world of side activities which are related to the world of Magic but are not directly part of the gameplay. The most important of these activities is by far the collecting dimension of MTG. This aspect of the game has been implemented in different ways by the various online games: some, like the official clients, have an economic model similar to the paper one in which the player ampliated its collection by winning matches or paying real money, others, mainly the various amateur versions, just allow the player to use every card he or she wants. However, none of these methods seem to be able to recreate the same emotion of the paper game.

“There is not the same component of staying at home with your friends or going to the local shop and winning or buying packs of cards. Even online there is a cost for playing, you still have to spend money and/or manage your resources in order to buy packs, but it is not the same thing.” (R7)

Players give a wide array of justification for this impression: the chance to customize the illustrations of their decks selecting different prints of the same card, the memories which are tied to certain objects, the satisfaction of being able to purchase the cards they wished during the adolescence with the economic means of an adult person…

“When you play a deck for a long time you also like to choose the illustration you prefer. […] Moreover, when I went to Liverpool for a tournament, I got my copy of Teferi signed by the artist. There is also this important aspect of the memories, there is a different relationship with the card. On Arena each card is like all the others.” (R13)

Among all the motivations considered the aspect of physicality of the game pieces is always central. The perfect physical conditions of all the game pieces are maintained in various ways like using protecting sleeves or, during matches, holding the card over a mat similar to the one used for the computer mouse in order to avoid getting them dirty. Most of the interviewed players seems to agree about the central importance of “holding the cards in their hands.”

“I like toying with them, I like shuffling the deck, I like seeing them, I like watching them. I do not like putting the protective sleeves, but you have to do it.” (R11)

“Trivially, even the sensation of shuffling the deck is a very nice physical sensation for me, which clearly I can enjoy only in the paper game.” (R6)

This pleasure of having and maintaining a collection is very closely tied to another side activity of the game: trading. Players can even meet only for showing each other their respective collections and eventually trade cards. For some players being skilled in concluding deals is almost as important as being good in playing the game:

“It was the most fun part for me. I went to tournaments not really for playing but for finding people interested in trading or even for the joy of seeing someone else’s collection. There was the guy good at playing but even seeing the one good are trading was a spectacle. I have seen some trades which were total scams, but the guy was so good in arguing that it was a spectacle in itself.” (R7)

The other aspect which creates a definite sense of involvement in the game is the interactions with other players perceived as individuals and not only as opponents to overcome.

Some players report the fact that the low interaction with other people do not allow them to really get involved in the game.

“I like the paper game most because you can speak. Trivially, you can say to the other: <Well done! This was a good move!> The other can say: <Look: you missed this!> and at the end of the game we chat a bit. (R6)

The players do not perceive the experience of online Magic as bad in an absolute sense, but they also believe that the software cannot give them the same level of human interaction which allows for complex exchanges like humor.

“I like the fact that you can be ironic about what is happening in the game, do you understand? As an example, a horde of squirrels which block and destroy the ancient god Emrakul. […] I can do it because there is someone there who is listening to me.” (R9)

This importance of the presence of other people becomes even more salient when playing with friends. The interviewees report that playing in a familiar context allows them to enjoy the situation even if the match they are playing is trivial or boring:

“Even a boring match becomes fun if it is spent with your friends: you make some puns, you laugh and you joke about what you are doing.” (R4)

Conclusions

The analysis of the interviews indicated a complex and sometimes contradictory world of interaction between players and the context in which the gameplay experience happens. While many intervening factors, like the level competitiveness of the game or the presence of friends, also contribute to the final outcome of the player experience, the choice of using tabletop or digital version of MTG undoubtedly has an effect on said outcome. This effect, divided in the four quadrants of the proposed framework, is:

- Low intensity/low valence: the online game seems to be more prone to repetitiveness and therefore boredom compared to the tabletop version. However, the increased number of possibilities given to the player and the chance to quit boring game situations partially counterbalance this effect.

- High intensity/low valence: anxiety seems to happen as consequence of the stakes of the game, regardless of the digital or non-digital context. However, frustration tends to happen when players experience the sensation of being powerless and in an online context, they tend to feel less remorseful about creating frustrating situations for their opponents.

- Low intensity/high valence: the accessibility and the simplification of the online version of the game may lead some of the more casual players to enjoy it when they are not concentrated on the activity, and therefore they have a milder experience. However, these traits also help new players in learning the game and in mastering its complexities.

- High intensity/high valence: the online version of the game gives the competitive player a place where they can test their skill and it seems to favor the chances of experiencing of the “automatic running” dimension of flow. On the other hand, the tabletop version of the game seems to create higher levels of absorption, since the online versions still struggle to recreate some important aspects of MTG like the collecting experience and the human interaction.

Overall, the tabletop game seems to be more immersive compared to the online version, while the latter results in a more comfortable and more accessible experience, especially for new players. However, when playing the online version of MTG, players seem to exhibit lower levels of empathy towards their peers. These results, while limited, are relevant for both the fields of game studies and game design. On one hand, it reminds developers of tabletop games who aim to port their products in the videogame world the difficulties of creating a healthy fanbase. The lack of empathy shown by the players of the online version of MTG and the idea that an online competitive videogame creates an inherently toxic environment are serious issue which should be addressed in planning the structure of an online community. Regarding the game studies field, this research underlines the importance of considering both digital and non-digital media in studying the interaction between games and players. While previous research has focused on the relevant variations in PX introduced by engaging with the same videogame on different hardware, the same issue is often underestimate regarding the divide between digital and tabletop games. This study proves that games like MTG are experienced differently not only according to the context in which the game is played but also according to the very objects which are employed during gameplay.

However, in considering these results it should be kept in mind that, as every exploratory research, this research only “scratched the surface” of the issue. Other studies with a more specific scope may delve deeper in aspects of player experience like flow of telepresence and give a more precise explanation regarding how these mechanisms work across digital and tabletop games. Another important limitation of the study is represented by the uniformity of the group of participants. Younger players with grater technological literacy may approach the digital version of a game differently than the older ones I interviewed. Also, the gender dimension may be relevant in this field since female players face more difficulties than their male peers in getting accepted by game communities and have to face higher levels of toxicity.

–

Featured Image by Max Mayorov

–

Giacomo Lauritano is a PhD student at University of Milano-Bicocca (Italy). His main research interests are Game Studies and Political Claim Analysis. In his research he focuses on how games contribute to shaping players’ conceptions of social interaction, values and politics. He is also an enthusiast player of needlessly long story-driven videogames and boardgames whose manuals have too many pages.

–

Appendix

Interview schedule

What do you like best about MTG?

Follow-up:

- What do you think is important for a satisfactory MTG match?

- Which situations are you making feel completely engaged in the game?

- Do you happen to feel bored or anxious when you are playing MTG

When you play MTG are you interested in feeling expert able to understand the subtleties of the gameplay or relax and have some mindless fun?

Follow-up:

- Would you compare playing MTG to watching an artistic movie or to something less demanding like an action movie?

Do you prefer playing the online or the tabletop version of the game? Which one is more fun for you?

Follow-up:

- Have you ever used Spelltable or played via webcam?

- Do emotions like boredom or anxiety happen in the same situation online and offline?

Do you believe there are some unwritten rules or good manners in playing MTG? Are these rules relevant even if you don’t know your opponent or you are not physically in the same room?

Follow-up:

- Do you think Magic Arena should allow more communication between players?

Do you ever happened to make new acquaintances while you were playing MTG?

Follow-up:

- Does it happen more frequently online or offline? Do you think there is a reason?