For two years in the early 1990s, I did larp onstage for a paying audience. None of us called it larp then, but in retrospect I’ve come to recognize the similarities of what I do now and what I did then. We called them “soaps,” and considered them live improv serial dramedies. Biosphere 2013 was neither the first, nor the last, soap to be featured at the Union Theatre, a small, black box, poverty theatre that lived a brief but vibrant life in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada in the late 80s and early 90s.

In this article, I’ll present an autoethnographic look into the production and address how it relates to analog games, particularly to live action role-play. I’ll describe the system of the production—including preparatory work, rehearsal play, scene lists, and performance improv—and have a look at similar techniques used in some genres of living games, specifically Nordic larp, black box, and Jeepform. I argue that the presence of an audience creates a radical reorientation in contrast to the larp environment, and explore how play changes when goals shift from the experiential to the outwardly performative.

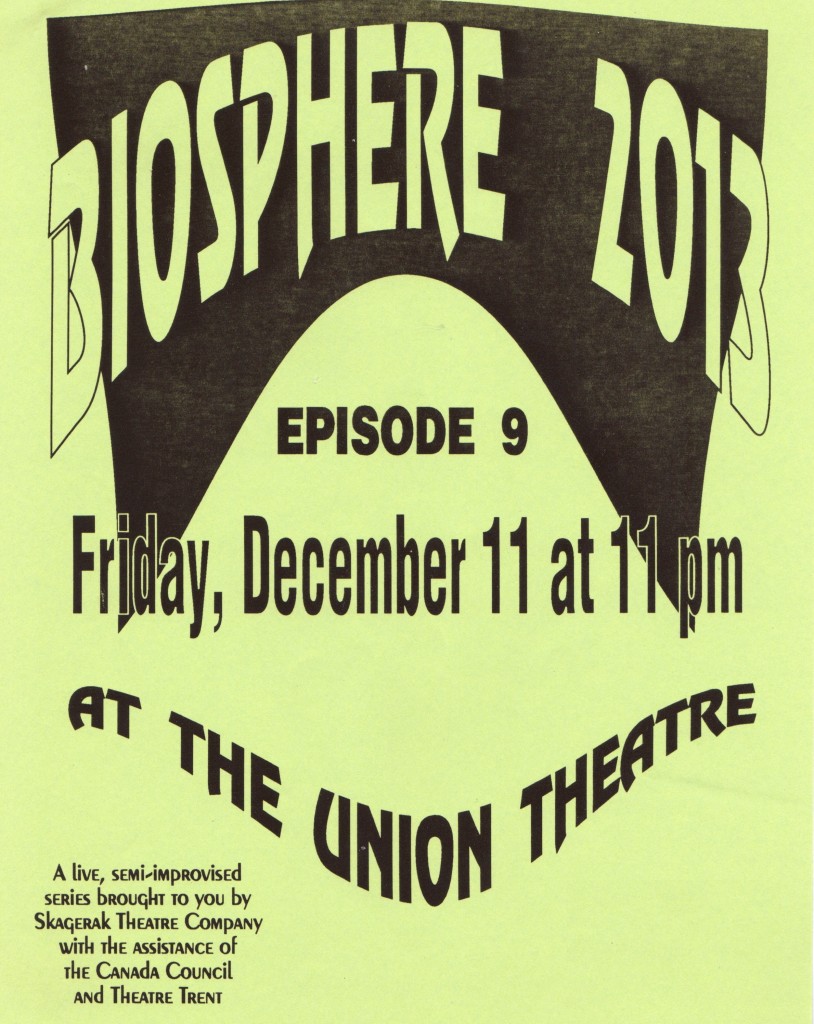

Biosphere 2013

Prior to initiating the production, the Director and the Creative Director (Frederik Graver and Kate Story), created a contextualization brief for the show. Set in a dystopian near-future of ecological collapse and corporate control, Biosphere 2013 aimed to explore ideas of autonomy, obedience, mind control, surveillance, and scarcity in an increasingly technological world. The context brief was a twenty-page document that spoke to the transition of society from 1990-2013 and described the formulation of the corpratocratic North American Intelligence Network (NAIN) government, and the development of climate controlled and regulated experimental biospheres that were meant to protect NAIN citizens from the toxicity of the declining environment. The document also described a resistance network of revolutionaries, neo-luddites and saboteurs that opposed the corporation. This document served as the first source of creation for the show; in role-playing terms, it was the setting and situation text.

The casting for the show was similar to many improv-specific theatre productions. A call for auditions was posted, responding actors were assessed through group improv exercises to determine their suitability, and callbacks were interviewed. However, despite the fact that the play had been “cast,” no specific roles had been developed for the production at the time of casting. Instead, characters for the show were developed through a long series of workshops and rehearsals that ran over the course of two months. A wide variety of personas were collaboratively invented by the cast through casual, non-canonical improv play within the setting and situation as established by the directors. Characters that didn’t work or create dynamic tension were discarded, and over the course of rehearsals key figures emerged that formed a cast of character prototypes.

Once the base cast was set, characters were firmed up in development rehearsals. Intensive hotseat interviews provided background, depth and interrelatedness to the characters, meditation exercises allowed the actors to turn inwards to understand their characters better, Laban movement workshops helped the actors construct and adopt character physicality, and voice workshops helped them find character voice. Finally, directed improv work with the directorial team put them in situations to test the tightness of interaction with each other and with the setting. Following this, the directors went back to the contextualization brief to include elements that had emerged through the rehearsals, and to eliminate elements that were not working, and set down the foundation of the show.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ArKgQUPPas

With the cast, roles, setting and situation set, the production was ready to launch. The show was produced in ten weekly installments, or episodes, on Friday nights after the theatre’s main scheduled production had let out. True to the form of a black box production, the show used minimalist lighting, props and costumes, experimental staging, and adapted to the set design of whatever show was being featured at the main production hour.

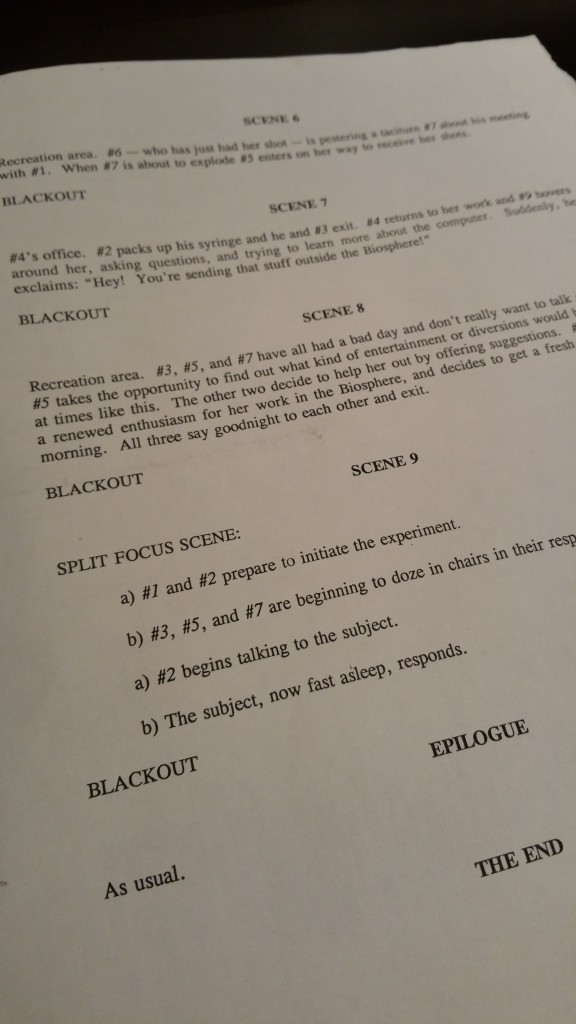

These soaps were neither devised theatre (a collaborative process that results in fixed performance piece) nor improv theater (fully spontaneous performances), but represented a hybrid model between the two. The dialogue, blocking and presentation was always improvised, but the structure of each episode’s narrative arc was devised by a directorial team and based on exploratory scenes that had been improvised during a rehearsal several days in advance. Each episode of the serial followed a cycle of production: on Wednesday evening before the Friday show, the cast would gather in a rehearsal space, and play out potential scenes for the upcoming episode. Cast members would have the opportunity to call scenes that would showcase their characters and introduce interesting plot points that they thought would bring good narrative value to the show. Directors could also call for scenes, or request a scene be rerun in several ways to understand its potential. The directorial team would then meet and construct a scene list for the performance itself.

On Friday night, an hour and a half before doors opened to the audience, the cast would gather in the performance space and the director would post the scene list up on a wall. The cast would gather around eagerly to find out what scenes they were in, and where the narrative direction of the show was going. The scene list would contain a structure for the episode consisting of eight to twelve scenes in which groupings of characters would meet in a named place and pursue a described objective. In the first few episodes, these scenes were written with detail, but by about Episode 3, when the process had matured, the scenes were brief, simple, and direct, and afforded the actors a greater range of improvisational liberty. Many scenes were variations of the scenes discovered in rehearsals, but each episode also contained new scenes and new ideas.

The ensuing hour would be a flurry of rapid engagement between the actors, who would pair up with scene partners to quickly discuss staging and blocking and agree on the mood and dramatic tension of a scene. The cast would explore the set design that the main production had introduced, and call out quick lighting cues to the technician. Finally, we donned costumes and makeup and squeezed in a quick vocal warm-up just as the doors of the theatre were opening. During the performance itself, the cast would self-direct, making entrances and exits according to the scene list, pre-show negotiations, and improv instincts, while managing timing and dialogue on the fly.

Because the format for this production was a legacy of a number of other successful improv soaps—The Coffin Factory (historical fiction), East Side Stories (soap opera), Hurricane Ridge (surreal mystery), One Red Shoe (Noir detective)—the show had a bit of a cult following that came back loyally week after week. The audience was engaged, high spirited, and unruly, equipped with the knowledge that their response in the moment and over time could shape or shift the direction of the scene or the show in general. They were vocal and sometimes outright rowdy throughout the performance, cheering, booing, heckling or cajoling the actors in order to spur a response to their demands.

Commonalities

There are obvious parallels between this production and larp in that the actors, as players, participated in the production through the locus of characters and drove action through them to create a narrative arc in a fictionalized world. They made decisions and built creative content based on a model of who their characters were, and how they would respond to the situation as contextualized. Not unlike a game master or larp facilitator, the directorial team acted as architects and gatekeepers to the production: they contextualized the situation, guided and organized play, acted as arbiters to the fiction, and essentially determined what was possible within the world of the show. And of course, actors physically adopted their character’s behavior, improvised dialogue and used costumes and props to enhance verisimilitude, as do many larps.

The production took place in the traditional context of a black box theatre and therefore it is unsurprising that it bears some strong similarities to larp and freeform practice in the Nordic arthaus tradition—particularly to Jeepform and black box scenarios that have been built on and informed by the traditions of experimental theatre. Techniques used during Biosphere 2013’s setup, rehearsals and production can also be seen in many Nordic arthaus larps. For example, character engagement meditations are used in Mad About the Boy (first run Norway, 2010), flashbacks in When Our Destinies Meet (first run Sweden, 2009), hotseat interviews in Pan (first run Denmark, 2013), and monologues in Doubt (first run Denmark, 2007). In addition, Play With Intent (2012) neatly illustrates how many of the techniques used in Biosphere 2013 are part of the common toolkit of structured freeform games.

Differences

First and foremost, the most crucial and obvious difference between Biosphere 2013 and larp is that it was performed for a consumer audience. This addition demands a paradigmatic shift in goal orientation for players/facilitators, which in turn fundamentally changes the production dynamic from play-as-participation to play-as-performance.

In analog game contexts, we rarely play with the intent of having an audience. The act of role-playing is centered on individual and communal fulfillment; that is, an individual plays because they like the experience of playing. Individuals play together to enable that experience, and because often the act of playing together is a critical component to enjoyment. In individual play communities or game designs, the theatrical quality of the game may also be an important component to enjoyment. These communities may include a notion of fellow-players-as-audience to enhance performance quality or social attentiveness. However, this concept differs critically from a theatre audience in terms of externality: even when we act as each other’s audience, we are still collaborating solely in the service of our own communal fulfillment. In a role-playing model, the goals of play serve the experiential satisfaction of the players themselves, individually or collectively. In the presence of an audience, the goal of play is to serve the experiential satisfaction of that external audience first and foremost.

This shift in goal orientation radically changes the entire network of engagement. Without an audience, the primary role of the facilitator is to help produce the play experience: they serve as a procedural guide through the game structure, a gatekeeper to the fiction, and a manager of the group dynamic. When serving an audience—particularly for a serial, such as Biosphere 2013—the director’s primary job is to curate the product of play: to monitor the satisfaction level of the audience, calibrate the narrative arc according to the audience’s enjoyment, and drive the players/actors to bring the best performance possible.

This change of directorial role in turn demands a shift in player/actor expectation. If a player’s experience is at the heart of the activity, then personal needs are prioritized: players have a reasonable expectation that their participation will be equitable, that their ideas will be incorporated, and that they get to decide what is good enough in terms of story, performance and play. But when an audience is at the heart of the activity, then players do not have the same expectations: they will be featured only inasmuch as their ideas or performance quality suit the production as assessed first by the directors and ultimately by the audience.

This creates a sharp delineation between play-as-experience and play-as-product. First, the concepts of player agency and narrative incorporation become fully independent from each other when play is in the service of product. For instance, in rehearsal play for Biosphere 2013, participants could take any action that fit the conceptualization brief, but nothing counted until it became incorporated into the scene list by the directorial team, and thus was scheduled to meet the audience. In essence, the players/actors held near-total agency for creating content, but zero agency for incorporating it, and had no mechanism by which to push their personal agendas, aside from anticipating and feeding the production’s goals in as high-skilled a way as possible.

Furthermore, the definition of “high-skilled” is much expanded in a play-as-product context. Role-playing generally requires robust imaginative thinking, rapid idea generation, theory of mind management, and social mediation skills. Larp further extends the skill demand to physical acting and emotional embodiment. However, larping for an external audience demands all of those skills ratchet to a new level because the audience has become the arbiter of quality, and therefore play must be proved to be “worth it” before it is integrated into the production. Furthermore, the social dynamic compounds: players no longer have to just forecast how their character thinks and how their fellow players (and respective characters) think, but also what the directors will think that the audience will want as well as how the audience will actually receive the performance. It no longer suffices for us to just understand and feel our characters and stories; we now have to also project them to the audience in a way that will enable them to form emotional connections with the production. Every participant must always be viewing their performance with an objective, assessing eye and steering their character actions and physical performance towards the audience’s satisfaction. To earn the ability to be featured in the Biosphere 2013 in significant ways was to master performance skills and the observer/performer calibration process.

It is also important to note that the soap audience’s active role created an enhanced demand for rapid incorporation of live feedback into fictional actualization without breaking the constraints of the episode’s frame and intention. When the audience did not like how a scene was progressing they would heckle, and when they wanted to see more they would cheer or shout out encouragement. Under a pressure framework of attention and timing to the production’s quality, the players/actors had to incorporate suggestions to serve the audience’s needs.

Conclusions

So how can knowing about a twenty-plus year-old black box theatre soap inform what we are doing today? First and foremost, it teaches us something about the relationship between goals and structures in games and how opportunities for design and experience are created. Looking at Biosphere 2013 through the lens of larp cleanly illustrates how changes in goal orientation demand different frameworks and dynamics for play. In the delineation between play-as-participation and play-as-product, devised and improvisational theatre hybridized to find a niche genre and create new opportunities for performance. This kind of cross-comparison of larp-on-the-borders with neighboring fields could create the same innovation for analog games.

Looking at larp through the lens of Biosphere 2013 demands that we question the strong demarcation often drawn between theatre and analog games. It asks us to look at what we take from theatre (e.g. techniques), to ask what we have left behind (e.g. the audience), and to examine validity and use value of some of the things we take for granted as basic rights of play (e.g. player agency). Shifting paradigms, even subtly, demands new structures and patterns of social engagement, creates opportunities to see how we might approach our games differently, and encourages us to explore how different the output of our play might be as a result.

Expanding the territory of the game field into the externally performative provides new opportunities for design innovation and skill development. New ways of being with our characters and the fiction open different loci of enjoyment for players to engage with. Just as larp itself provides a new platform of exploration for players with a desire to physically engage with characters and fictions, performative larping would, for some players, extend that opportunity further, or in new directions. Players who have a strong desire to develop performance techniques may find the demands of a performative larp helpful in achieving those goals, and players who find fulfillment in character enactment and performance may find new vistas of satisfaction in play when in front of an audience.

Finally, it’s worth noting that designers on both sides of the equation are playing on these boundaries already. The experiential theatre world seems to be entering a new renaissance where improv, performance, and audience interaction are creating such innovative productions as Sleep No More and Then She Fell. In larp, Nick Smith and Jake Richmond and Jackson Tegu’s Sea Dracula (2008) is played with the help of an audience who deliberates on conflicts as expressed through physical dance-offs. Furthermore, two of Jason Morningstar’s larps in development venture strongly into a play-as-performance model. Ghost Court (2015) is a high-spirited courtroom comedy about ghosts and people pursuing small claims cases against each other and includes a gallery-audience of observers (who may or may not become players), and a dynamic of brief interactions that encourage players to ham scenes up for an increasingly rowdy audience. The Dream (2015) finds a fascinating niche between larp and silent movies, pushing the ephemeral nature of play-as-participation into the endurance of play-as-product when the game produces a literal short silent movie that can be shared as a persistent artifact of play.

—

Featured image by James Joel on Flickr, licensed under CC BY-ND.

—

Moyra Turkington is an award winning Canadian larpwright, game designer and theorist with a background in Cultural Studies and Theatre. She currently writes for Gaming as Women and Imaginary Funerals and her older ideas can be found on Sin Aesthetics. She is interested in immersive, transformative and political games, and particularly in creating a multiplicity of media, design, representation and play.