As the work of Ian Bogost, Mary Flanagan, Miguel Sicart has ably demonstrated, playing is not “an act apart” (Huizinga) Recent responses to analog games, both mainstream and academic, make it abundantly clear that tabletop games, as an enduring mode of cultural representation, are deserving of closer critical scrutiny both for the ways in which they depict their subjects and for the ways in which they position their players. In their discussion of colonialism in board games, Cornel Borit, Melania Borit, and Petter Olsen quote Stuart Hall to good effect in their analysis of the ways in which games situate their players in relation to the narratives they construct [here I expand the opening of that quotation]:

every discourse constructs positions from which it alone makes sense. Anyone deploying a discourse must position themselves as if they were the subject of the discourse. For example, we may not ourselves believe in the natural superiority of the West. But if we use the discourse of “the West and the Rest” we will necessarily find ourselves speaking from a position that holds that the West is a superior civilization.

Hall’s discussion of the discourse of “the West and the Rest” recalls to mind Bernard Suits’ account of the voluntary submission to a game’s rules, make sense only to the player who adopts the appropriate lusory attitude in which “the rules are accepted just because they make possible such activity.” As Claus Pias (whose work David Parisi discusses to great effect in an earlier paper in this journal) remarks in his discussion of games as material objects, “[at] the interface, not only do players take control over a game, but a game also takes control over its players.”

As Marie-Laure Ryan notes, “[t]he major objection against immersion is the alleged incompatibility of the experience with the exercise of critical faculties.” If, immersed in the games we play, we find ourselves “transported” to an simulated place (Murray), “recenter[ed]” as Ryan puts it, it remains incumbent upon players to ask, to where have we been transported? What, exactly, are we playing at?

In this essay, following Rafael Bienia’s work on the materiality of play, my focus is on the “messy tabletop” on and around which “material actors collaborate with narrative and ludic actors,” and responds, albeit in a tangential manner, to David Parisi’s observation that “interfaces are expressions of power.” Impelled by a concern to account for the affordances of analog game platforms, I argue that their tactile mechanics facilitate immersive gameplay through – rather than despite – their sometimes clunky, clumsy, “ergodic”, and always material, demands.

At the same time, the materiality – the “mess” – of tabletop games, resists the fantasy of immersion as escapism. Just as Bienia’s “role playing materials” (lights, tables, battle maps, character sheets, pencils and games master screens) are “materials that are [themselves] role-playing,” the tokens of my title are tokens that “gesture.” Like Bienia’s, my title is a play on words, intended to suggest the manner in which the tokens of analog games, which ostensibly anchor the player within the horizon of the gameworld, simultaneously gesture (vertically) to the world of the player, initiating for the players an unsettling, and, I will argue, productive, oscillation of subject positions.

Standees and standing-in

The sense of the board game token as a “stand in” – “One who fills the place of or substitutes for another” (OED) – recalls Daniel Kromand’s definition of a video game avatars as “a game unit that is under the player’s control.” Both token and avatar suggest the player’s being-with, rather than being, the playing piece – a sense that is neatly captured by board gaming’s ubiquitous “meeple,” a term derived from a contraction of “my” and “people.” Certainly this is the kind of relationship seen in many classic games in which they often take the form of predetermined, steerable entities, occupying and marking space within a specific (cardboard) gameworld. Having noted this, emphasizing puzzle-based immersion over imaginative immersion, fails to adequately account for the properties of the large number of highly-thematic games in which players are invited to identify with (and perhaps as) the characters within the storyworld.

Ade M. Campbell @Flickr CC0 1.0

In what follows I attempt to map out some of the possibilities for imaginative (identificatory) immersion in analog games, while noting the opportunities that arise from the analog game’s limitations when it comes to creating the kinds of experiences that have traditionally been seen as the remit of literary, and latterly digital, story worlds. Janet Murray’s influential early account of immersion in Hamlet on the Holodeck acts as my starting point:

Immersion is a metaphorical term derived from the physical experience of being submerged in water. We seek the same feeling from a psychologically immersive experience that we do from a plunge in the ocean or swimming pool: the sensation of being surrounded by a completely other reality, as different as water is from air, that takes over all our attention, our whole perceptual apparatus.

In this definition, written in a language suggestive of baptism, Murray suggests that immersion is not so much a sense of engagement with another world as it is a sense of being in that world. However, while suggesting that the immersive experience “takes over all our attention” Murray argues that immersion relies on an awareness of the “threshold object[s]” – the screen, the mouse, joystick or database – that separate the world of the player from that of the game. It is the awareness of these threshold objects (the tokens, boards, dice and cards of tabletop games) that both draws the player into the gameworld and maintains its boundaries as a distinct space. A similar concern with the interaction of players and games prompted Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman to ask:

What if game designers focused their efforts on actively playing with the double consciousness of play… Imagine the kinds of games that could result: games that encourage players to constantly shift the frame of the game, questioning what is inside or outside the game.

Responding to the challenge to imagine such games, games that play with the doubled space, and with the experience of immersion, the remainder of this essay works through three case studies: Jean-Yves Monpertuis, Gaëtan Beaujannot et al’s Flick ‘em Up: Dead of Winter (2017); Todd Breitenstein’s Zombies!!! (2001); and Isaac Vega and Jon Gilmour’s Dead of Winter (2014). In examining these three very different games my aim is to draw attention to the ways in which analog games, which take place both on and around the table – generate immersion by exploiting the ambiguities of these intersecting play spaces and to suggest that this awkward, messy, doubled space might enable the kind of critical distance necessary for the generation of interrogative, if not transformative, play experiences.

Touching on games: Flick ‘em Up: Dead of Winter

In the manifest physicality of their paper, card, wood, and plastic technology, analog games might make a claim to be better placed to engage with the senses of their players than their digital counterparts. Characterized by the high production values of their components and artwork, contemporary board games appeal directly to the senses of touch and sight and on rare occasions to taste (Scrabble: Chocolate Edition, 2007; Cooking with Dice, 2017), smell (Spice Navigator, 1999; Adventure Scents, 2015; The Perfumer, 2016), and hearing (Igloo Pop, 2003; Stop Thief, 2017). Nonetheless, such appeals to the senses do not necessarily equate to sensory immersion in the manner that it is described by Murray. More likely, the threshold objects of analog games foreground the distinct worlds of player and game, forestalling any easy transportation into the gameworld.

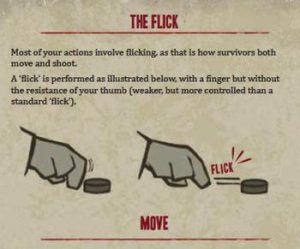

The impact of the material qualities of the analog platform, and the relation of player to the pieces under their control, is experienced at a fundamental level in dexterity games such as the zombie-themed Flick ‘em Up: Dead of Winter (2017). As the second-person address of the game’s scenarios suggests – “You can hear a fellow survivor in distress! But where are the shouts coming from?” – players take on the roles of the survivors of a zombie apocalypse, the tabletop representing a decaying urban wasteland. As such the game invites a certain level of identification between players and their plastic avatars, but ultimately the gameplay, in which players propel their playing pieces across the board by flicking wooden “movement discs,” relies on the disjunction between player and piece. Flick ‘em Up is fun because it is awkward.

The “flick,” with the attendant the impact of finger on token, and the sound of finger-nail on plastic, is a physical reminder of the distinct worlds of player and playing piece, suggesting a playful disconnect between player and in-game avatar and locating the game’s immersive properties within the threshold objects that facilitate entry to the gameworld.

While dexterity games, which entail a certain level of physical challenge, provide perhaps the clearest example of the impact of the physical components on gameplay, the haptic aspects of analog games might generally be said to act as thresholds which both make entry into gameworlds possible while simultaneously barring players from complete entry into the very spaces that they create.

The duality of this border, as invitation and as obstacle, is perhaps a quality of the sense of touch itself. Touching is, as Jacques Derrida has remarked, an act that entails “touching what one touches, to let oneself be touched by the touched, by the touch of the thing.” As Mark Paterson puts it “[t]he feeling of cutaneous touch when an object brushes our skin is simultaneously an awareness of the materiality of the object and an awareness of the spatial limits and sensations of our lived body.” A consciousness of self as both subject and object emerges in this doubled touch, and in the case of games (including those in which haptics may be used to facilitate immersion) clearly marks the threshold between the player’s world and the game space.

Props, Tokens and Avatar-dolls: Zombies!!!

While Flick ‘em Up: Dead of Winter draws on the affordances of the analog to generate play through the physical distinction of player and playing pieces, Todd Breitenstein’s Zombies!!!, in which players race to be the first to escape a zombie-infested cityscape, encourages players to identify with their in-game characters. It is a familiar narrative – zombie apocalypse, every man (predictably it is a man) for himself, “first to the helipad wins.” Essentially a roll-and-move game, with a randomly-generated tile map and a basic combat system, Zombies!!! puts its players in direct conflict through the use of action cards that allow players to increase their own chances of victory while diminishing those of their rivals.

In line with thematic hobby games generally, Zombies!!! combines puzzle-based and imaginative immersion. Its rules and components function as what Chris Bateman, following Kendall Walton, calls “props” – “something which prescribes specific imaginings” – to recreate a 1980s schlock-horror aesthetic through the inclusion sculpted figures and fully-illustrated map tiles and cards. Thus while it would be possible to disaggregate mechanic and theme, Zombies!!! facilitates specific fictional imaginings, inviting players to identify with the game’s protagonists as they traverse the zombie-infested storyworld.

The complex relation of player and playing pieces suggested by such a model of imaginative and identity based immersion are manifest in the way in which Zombies!!! addresses its players. Its four-page rulebook employs a number of terms: “player”; “dealer”; “pawn”; “shotgun guy” (these two interchangeable); and the helpfully-immersive “you” which George Vasilakos, creator of the role-playing game All Flesh Must Be Eaten (1999), uses to good effect in the game’s introduction:

What you hold in your hands is a little game that gives you a chance to re-enact the suspense and fear of trying to escape the clutches of the walking dead. When it comes to survival, it’s every man for himself! Don’t worry about your high school buddy or what your girlfriend will think (you can always get another). When you leave them behind or give them a gun and forget to give them the extra ammo, you’ll be the one laughing your way to that safe island in the Caribbean away from the zombie outbreak…

This near-characterless second-person address affords acts of imaginative identification not so much through thematic detail as through a generic emptiness. This noted, it is a typically “masculine neutral,” that reveals not only the gender bias of the games industry, but also the imaginative challenge players may face in identifying with in-game protagonists.

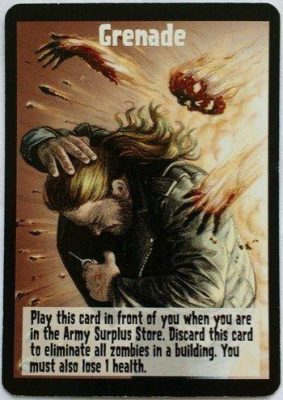

The potential misalignment between the largely-but-not-quite empty second-person address and the reader is indicative of the board game’s always-doubled space. In the opening sentence, “you” clearly designates the person holding the game. In the next sentence this “you” transports the player to the storyworld, “When it comes to survival, it’s every man for himself!” In a game in which aggressive competition is mandatory, the next line is ambiguous, “Don’t worry about your high school buddy or what your girlfriend will think…” These words might refer to the player but could equally apply to the in-game character. This use of a doubly-deictic “you” continues during gameplay. The event card “Grenade,” for example, reads “Play this card in front of you when you are in the Army Surplus Store. Discard this card to eliminate all zombies in a building. You must also lose 1 health.” Thus the player of the card is located at the table (on which the card must be played) and “in the Army Surplus Store” where zombies will be destroyed and lives lost.

This duality is not so much the result of imprecision in the writing, as it is a necessary element of the analog game platform, and here David Herman’s description of the doubly-deictic nature of second-person narrative as an “ontological interference pattern produced by two or more interacting spatiotemporal frames” might be usefully applied to the necessary interrelation of players and games. While this applies to both the analog and the digital, in the former the “interference” is perhaps more immediately apparent in the physical interaction of players and playing pieces.

In Zombies!!! this ontological interference manifests itself in the shift from the second-person address of the rulebook to the third-person perspective of the tabletop game. In line with the dual perspective of the rulebook’s “you,” the game’s tokens – “6 Plastic Shotgun Guys (Pawns)” and “100 Plastic Zombies” – sculpted by Behrle Hubbuch – function on two levels being both (enabling players to navigate a game’s story world) and representational (gesturing to something beyond themselves).

Bateman’s work on prop theory is helpful in articulating the way in which these plastic figures (“pawn-props”) fulfill the necessary mechanical function of distinguishing between players and antagonists while denoting their locations on the tile-based cityscape (the “board-prop”) while also performing a representational role within the game by prescribing specific fictional imaginings on the part of the players. In this dual function, the playing pieces included with Zombies!!! function as what Bateman calls “avatar dolls,” a term that brings together “avatars,” “our capacity to act within that world,” and “dolls,” the “prop that prescribes we imagine the details of our presence in the fictional world.”

Play at the Borders of the Magic Circle: Dead of Winter

Turning to my final example, Dead of Winter, I want to argue that the doubled nature of board game pieces – as both avatars and dolls – is a key affordance of analog games. The inherent duality of the gaming piece, which provides a means of entry into the game space while simultaneously insisting on the distinction between the worlds of player and game recalls Salen and Zimmerman’s call for games that explore the edges of gaming’s “magic circle.” Dead of Winter is arguably an example of what such games might look like.

Dead of Winter is a semi-cooperative game in which players take the role of survivors of a zombie apocalypse, working together to achieve a shared “colony” objective. This usually entails fending off the walking dead while searching for supplies and maintaining morale. The game is only semi-cooperative because in addition to the colony objective each player has a secret individual objective, and winning the game requires that both colony and personal objectives be fulfilled. In addition, there’s a chance (one-in-nine in a four-player game) that one player will be given the objective of betraying their fellow players, working to undermine the group’s efforts. That player wins if everyone else fails. To readers of Robert Kirkman’s The Walking Dead (2003-) the sense of mistrust this generates between players will be familiar. Thus the game institutes two levels of play – that on the board and that around the games table, and one of its main strengths is in the way in which it plays with the border between the two.

One of the ways in which Dead of Winter achieves the balance between its various levels is through the meticulous care with which it distinguishes between the players and the survivors under their control, only relaxing its terminology in the flavor text that accompanies the game’s objectives. The tokens used to represent the survivors underscore this distinction. Their primary function is to indicate the relative locations of the players’ characters on the board. Their secondary function is thematic – they’re fully-illustrated renderings of stock characters from popular zombie culture. In both roles they serve to differentiate between player and piece. In terms of location they signal the different spaces of the gameworld (in which the cardboard survivors exist) and the world of the player.

In terms of theme, the “fully-drawn” survivors make clear the distinction of player and character, forestalling any easy immersion in the gameworld by leaving little blank space onto which players might project their own identities. As Bateman puts it, “if the avatar is understood as a prop intended to prescribe that the player imagines they are in the fictional world of the game, a less imaginative player can be ‘priced out’ by a doll that bears absolutely no resemblance to them.” Accordingly, the standees of Dead of Winter, particularly those that are recognizable to players familiar with the tropes of zombie fiction and film, are objects that players control in a manner that is not entirely dissimilar to the everyday objects, the boot and the iron, of Monopoly.

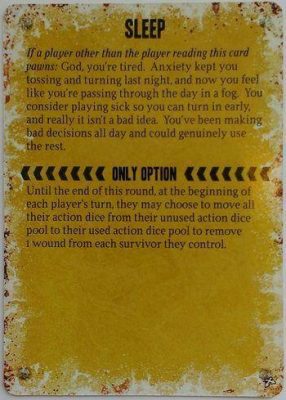

At the same time Dead of Winter’s gameplay relies on a complex relation between players and survivors that undermines just this distinction. While the physical components of the game signal the separation of player and character, the space between these two worlds is bridged by the game mechanics as the paranoia and mistrust of the survivor colony is recreated in the real-world relationships of the game’s players who must work throughout to ascertain the motivations of their fellow gamers. This blurring is captured well in two of the in-game cards which conflate the world of the game with that of the players.

“Sleep,” for example, triggers “If a player other than the player reading this card yawns.” Similarly, “Megaphone” invites requires real-world actions (“When placing this card in the waste pile shout what you said into the megaphone”). As these cards suggest, Dead of Winter manipulates player expectations relating to the “inside” and the “outside” of the game, and while they might appear to be novelty items that threaten to undermine immersion, they are indicative of the game’s broader structure. The experience of pursuing secret “betrayal” objectives requires “real” players to keep “unreal” secrets on behalf of their in-game avatars, for whom, of course, these secret objectives are a reality. In this way, play takes place in an unsettling, because unsettled, third game space that emerges when play oscillates between the tabletop game space and the space occupied by those playing the game. In other words, immersive gameplay emerges from a misrecognition of the game’s location that is made possible by the always-manifest materiality of the game’s “threshold objects.”

Conclusion

In his seminal essay “Thing Theory,” Bill Brown makes the observation that “[w]e begin to confront the thingness of objects when they stop working for us […] When the drill breaks, when the car stalls.” My suggestion is that the recognition of the “thingness” of analog games, the point at which their cardboard mechanics are most manifest, is the point at which they begin to work. Moreover, it is at this point at which point they might be usefully put to work in the sense suggested by Mary Flanagan in Critical Play when she asks, “What if some games, and the more general concept of ‘play,’ not only provide outlets for entertainment but also function as means for creative expression, as instruments for conceptual thinking, or as tools to help examine or work through social issues?” It is, as Jess Marcotte puts it in an important recent Game Studies article, “in these gaps, which resist flow and immersion, that reflection upon the queered, reoriented nature of the experience can occur.”

To be immersed in these analog storyworlds, is, then, to occupy two spaces simultaneously, and at points it becomes difficult to distinguish between the “inside” and “outside” – the game and the meta game. Thus immersion in board games should be understood not in terms of the transportation of the player to the world of the game (through an identification with the token-avatar) but in a broader sense in which the game world extends beyond the game and into a zone that is proximal with that of the player’s actual world, creating both friction and design opportunities.

It might be argued that this is accounted for in discussions of the “meta” games, which Richard Garfield, the designer of Magic: The Gathering, describes as “what a player brings to the game [training]… what a player takes away from a game [reputation]… what happens between games [reflection]… [and] what happens during a game other than the game itself [trash talk].” But the notion of the metagame, where “meta” carries the sense of levels, or “after,” is unhelpful. The question in Dead of Winter is not how the levels of the game relate (as is the case in Zombies!!!) but rather where the borders of the game space are drawn. In effect the board itself, and the table on which it sits, make possible a deliberate misdirection that leads players to envisage play as leveled in the manner of a traditional board game. And of course they are, the social metalevels do exist, but the border of this game’s “magic circle” is wider than might be expected, encompassing the metalevel and conflating it with the world of the players. In many contemporary board games what has been called the metagame is not “after” or “beyond” the game at all but an aspect of the game itself. As Stewart Woods puts it in Eurogames (2012), his words gesturing towards the potential that board games have to collapse the “meta” of the metagame: we are “Never Not Playing.”

To conclude, analog games are bound by their materiality, by their location (the kitchen, the games room, the café), the tabletop, and by the worlds of their components, which occupy a dual space between the two, existing materially in “our” world and imaginatively in the world to which the components function as an invitation. These notes towards a theory of analog immersion remain a work in progress. Among other things it seems necessary to properly account for the visual/artistic aspects of a medium that is increasingly characterized by high production values, along with the rapid development of digitally augmented games (e.g. Eric M. Lang’s XCOM: The Board Game (2015) and Nikki Valens’ Mansions of Madness (2016)) that bring in aural elements that have been left to one side). Similarly, future work is needed in order to work through in more detail the implications of the ontological claims made about the relation of players and the pieces with which they play.

–

Featured image by graham mcallister @ Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0

–

Paul Wake is a Reader in English Literature at Manchester Metropolitan University and a co-director of the Manchester Game Studies Network. He has published on literary representations of casino games, 80s Adventure Gamebooks, and game design for communication. He also writes for Tabletop Gaming Magazine, and designs, uses, and plays games to start conversations about important societal topics.