“Some have billed Bazaar as an educational game, and I don’t think that’s strictly correct. It’s true that there’s little or no theme here, and that the heart of the game is an abstract exercise in efficient exchanging of the stones. So it could be argued that the game is really just an exercise in algebra, since the formulas on the exchange cards are little more than equations, and players must try to optimize these equations to arrive at combinations that earn the most points. While there’s truth to this, [sic] yet the game doesn’t at all feel like a dry exercise in math or logistics. Reading comments from others, it seems that I’m not the only one who was pleasantly surprised to find the gameplay more enjoyable than expected.”

The above epigraph, from an online review of Sid Sackson’s board game Bazaar, exemplifies a common assumption about the designer’s opus–namely, that Sackson’s games are without a significant theme, and that this lack of flavor endangers the potential fun of his designs. The present essay investigates and challenges these assumptions through a close textual analysis of the rulebooks in many of Sackson’s pioneering games. We contend that Sackson’s games may not be rich in theme, but his selected themes are nevertheless sensible and significant because they amplify his desired play experience of outsmarting your opponent (what Sackson calls the intended player experience of “gotcha”). This amplification may in turn help explain the enduring popularity of his designs. We begin our investigation here with a consideration of Sackson as a designer and larger debates about theme in the eurogame genre. We then turn our attention to analyzing Sackson’s rulebooks, proposing the outsmarting of opponents as the link between these games’ designs and their various themes. Finally, we conclude with some reflections on how this analysis might contribute to considerations of theme in analog game studies.

A Brief Biography

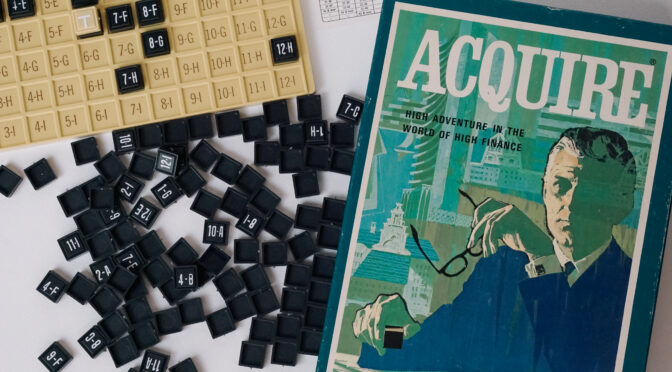

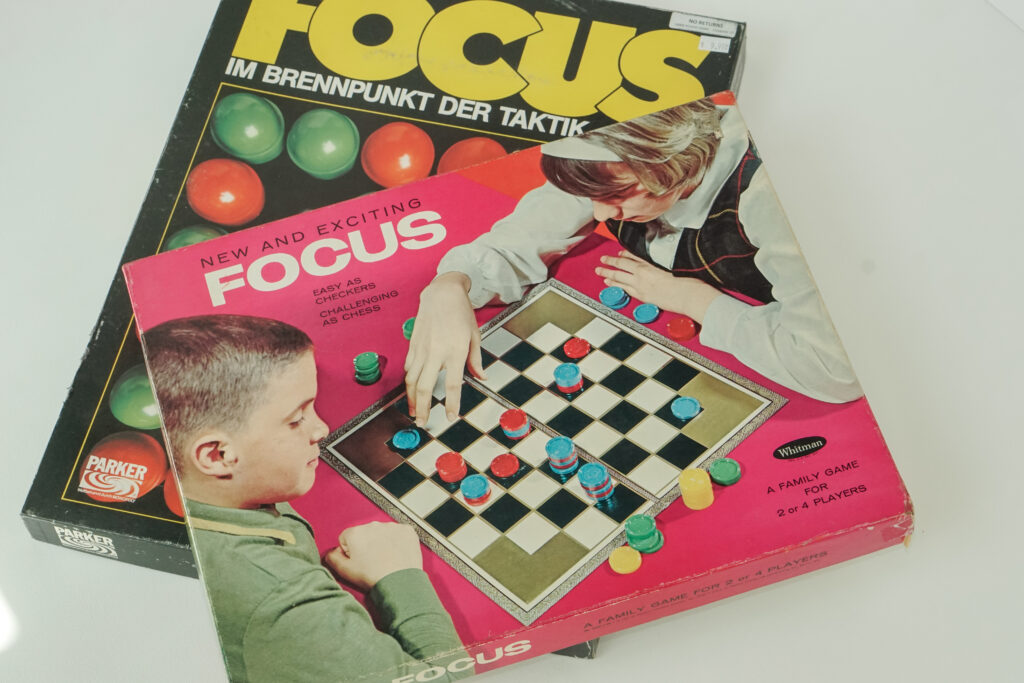

Sidney “Sid” Sackson (1920-2002) was America’s first celebrity game designer (or “inventor,” as he preferred to be known). Working most prolifically from the 1960s until the late 1980s, he designed over 500 games, around 50 of which were commercially released. He was the first American designer to successfully negotiate that his games would be published under his name, with the publication of one of his most successful commercial board games: Focus by Whitman. This game would later win him the 1981 Spiel Des Jahres in its later imprint, making him the first American to win this prestigious German gaming prize. In truth, Sackson’s win of the Spiel only underscores the widely-held sense that despite his nationality, he might be rightly ensconced as “the founding father of the German-style game” or eurogame. As Stuart Woods observes, Sackson’s 1964 game Acquire features “most of the hallmarks that would later come to typify the eurogame: an emphasis on an abstracted system over theme, a relatively short and clear ruleset, manageable playing time, and a lack of player elimination.”

In the early 60s, Sackson became a pampered figurehead for the 3M company, taking time off from his day job as a civil engineer to be flown first-class around the US as he marketed its bookshelf collection of “All American” game titles on radio and television. During his relationship with 3M, Sackson published most of his most well-known games, including the aforementioned Acquire and Bazaar, as well as Sleuth, Venture, and Monad. Despite this wide celebrity, Sackson returned to his engineering career to work on varied military (naval) and large-scale building projects until he eventually left the profession to focus on games full time in the 1970s.

Sackson was a consummate night owl, preferring to take calls only after 11 pm, and he labored on his game prototypes and reviews for the popular gaming magazines of the 60s and 70s late into the night. He kept copious notes and diaries all through his life, cataloging all of his correspondence with other designers and manufacturers, as well as keeping notes on his and others’ designs. This catalog and his enormous game collection of over 15,000 games resided in his modest home in the Bronx, NY where he lived for most of his life with his wife Bernice and their children.

Sackson participated in multiple gaming groups throughout his life, but Bernice and Sackson also seemed to delight in inviting fellow gamers over to the house for a more intimate evening of dinner and games. Wayne Saunders described the experience of such a meeting with more than a little awe: “His delight in games was my own, but his analytical depth and canny imagination were locked in away in a place I couldn’t visit, where, though there was so much to the man to make up for it, even Bernice, probably couldn’t follow.”

Described by Alan (Al) Newman as “forever competitive” even into his old age, Sackson passed away in 2002. Due to the diligence of his friends, the archive of his papers and diaries (along with several hundred game prototypes) is in the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, NY. Sackson’s own collection of games was auctioned off in parts soon after the resolution of his estate, with many of the games stamped with the mark “From the Personal Collection of Sid Sackson – signature”. Even posthumously, then, Sackson was the consummate self-promoter, and these stamped games are widely collected today.

Theme as Heuristic in the Eurogame Genre

Especially because Sackson is often referred to as a central designer in the history of modern eurogames, understanding larger discussions of theme in this genre help ground a consideration of theme in his specific designs. The role and importance of theming in eurogames is debatable. One prevalent understanding argues that the theme provides players with artistic and narrative materials that will help them internalize the intricate mechanisms central to the genre. Put differently, the theme of a eurogame–its setting, art, and “story” that unfolds over the course of play–is meaningful to the degree that it helps clarify available player actions, rationalize the prescribed values of different components, or remind players of exceptions to rules that they might otherwise easily overlook. Woods summarizes this perspective by contrasting the works of game scholars Markku Eskelinen and Aki Järvinen:

Eskelinen argues: Stories are just uninteresting ornaments or gift-wrappings to games, and laying any emphasis on studying these kinds of marketing tools is just a waste of time and energy….However, as Järvinen argues, the ornamental nature of game themes do have consequences for player experience. Describing the theme as a “metaphor for the ruleset,” he proposes that in creating such a metaphor, an extra level of meaning is created “for everything that happens in the game.”

Importantly, though Eskelinen and Järvinen disagree on the worth of critically scrutinizing theme in the study of eurogames, they both readily recognize that it is secondary or beholden to the underlying structure of the game itself.

From this vantage point, the specific theme of any eurogame might be judged favorably to the degree that it beautifies or bolsters the mechanics of play. As game developer Brandon Rollins puts it, good themes “keep us from feeling like we are playing out the logical conclusions of mathematical functions,” a feeling that principally occurs when the “inner narrative” of a game (or the synthesis of theme, story, art, and components) “reinforce[s] the game’s mechanics and rules.” Tzolkin, The Mayan Calendar is an example of strong unity between theme and mechanics in eurogame design, where players’ patient investment of resources unfolds against the setting of a civilization highly organized around time. Conversely, a eurogame theme can be judged unsuitable, or at least incidental, when it fails to deliver in this regard. Such judgments commonly occur when a game switches themes between editions. In 2011, for example, Queen Games released Dirk Henn’s New York, a game that mechanically mirrors his award-winning 2003 design Alhambra but updates the setting and art from Granada, Spain to the Big Apple. Many board game hobbyists found the update baffling and unnecessary. “If you want to play Alhambra but are too much of a bigot or even simply hate good art,” writes one user at Board Game Geek, “New York…is the game for you. For everyone else, just play Alhambra.” In fact, derision about the interchangeability or relative unimportance of theme for many games in the genre is prevalent enough that one of the authors of this study recently witnessed a shirt being sold at a major board game convention with a humorous advertisement for “Euro’s Theme Paste.” Done up in the style of an antiquated Sears catalog entry that featured a squat, dark bottle, the fictional product nevertheless promoted itself with a very real sentiment of some in the gaming community: “Because Any Theme Will Do.” In sum, then, we would venture that the most charitable understanding of theme in eurogames promotes it as a heuristic, or means of improving understanding of the game’s rules, while a sizable portion of hobbyists also understand it as relatively meaningless gloss; an aspect of the game merely “pasted on” at some point during the design process.

Both of these sentiments appear in popular reviews of Sackson’s designs on BoardGameGeek. In a review of Acquire, for example, a user opines “I think this game represents the stock market in a very fun, realistic format, that is very easy to teach to new gamers, and can be enjoyed time [sic] and time again.” In other words, the business theme of the game readily acclimates new players to the game design and helps returning players remember the game between plays, resonating strongly with the view that theme is merely a heuristic for gameplay options. The second perspective is present in a review of Sackson’s game Samarkand, a game about purchasing and trading goods in central Asia. “The theme could be anything around the selling and buying,” writes one reviewer. “[T]here is almost nothing to do with [S]amarkand city.” In both cases, however, there is a sense that the game theme is incidental compared to Sackson’s core design. As cultural critic Ben Schwartz observes in relation to the common focus on finance and capitalism in Sackson’s games, a motif we will return to ourselves later: “[It’s] hard to say now what he really thought of the [economic] system outside of a theme for board games.” Schwartz goes on to suggest that, while Sackson was likely enamored with the theme of money because it was a good way to attract adult audiences to play his games, the designer’s sense of his themes as a way for players to meaningfully explore economic ideas is far more fraught and speculative.

Method

Our research can be characterized as a form of thematic content analysis both in a conceptual and methodological sense. The material consists of rule books from ten North American published Sackson games spanning the dates 1962-1982, the height of Sackson’s popularity. For each game, we used a first edition game to obtain the rulebook. Thematic analysis is a good fit as an open-ended methodology that would allow us to explore our initial research questions: What, if anything, is the relationship between theme and mechanic in Sackson’s games? Is the theme as unimportant as is sometimes claimed in these games? In other words, is it correct to say that Sackson is an “abstract” game designer, as befitting his reputation?

Thematic analysis involves a practice of “open” coding of material, followed by organizing these codes into trees (or hierarchies) primarily. This initial organization of data is described by Bazeley (2013) as a series of “read, reflect, play and explore strategies.” The data is then arranged more meaningfully into sections, at which point critical arguments can be made for or against the research questions. Because this process is naturally an iterative practice, we addressed inter-rater reliability partly by using the computer-assisted coding software Dedoose, but we also coded cooperatively and re-coded in our initial exploration in a strategy that reflects our shared position on the data. As Waller et al. argues: “Within these research paradigms, it is more customary to think of team-based coding practices as socially constructed, based on discussions and negotiations between different members of the team.”

As a starting point for our coding, we used a framework drawn from Woods’s book on eurogames, thinking seriously about his position on the classification hierarchy of “thematic models” and “thematic goals.” We found his thematic models –– Miscellaneous, Fictional, Contemporary, None, and Historical –– to be overly broad as descriptors, so they did not contribute much to our coding process. Thankfully, Woods is not the only author to suggest thematic models or groups for the understanding of board games. In the Oxford History of Board Games, Parlett suggests ten thematic groups: Business and Trading, Detection and Deduction, Crime, War, Fantasy, Alternative History, Politics, Sports, Word Games, and Social Interaction and Quiz Games. Given the diversity in what thematic groups to use, the concept of “thematic goals” was a more useful starting point for our thinking, though we do not agree that all player actions are thematic in the same way that Woods does, and we have consequently separated them out in our own analysis. Thus, in our mind, the approaches to thematic models and goals as Woods uses them are more inspirational or heuristic in nature. Ultimately, we refined the tree that we used for our coding to categorize each game in four ways.

First, we found it most useful to establish the main mechanic of the game as board game enthusiasts might conventionally describe it in popular media (e.g. area control, set collection, etc.). We reject the approach that authors such as Järvinen embrace to create a universalizing theory of all games by using the term “mechanic” to capture theme as well. Second, we attempted to decide on the main theme of each game “organically” or inductively, through textual analysis of the wording choices of the rules. Third, we considered on a game-by-game basis the thematic goals of each game–that is, the major thresholds internal to each game that a player must accomplish to win. Last, we coded and cataloged any thematic elements in service of those goals, such as “hotels” and “mergers” in Acquire. Of course, not all of Sackson’s games have all of these levels well represented, though (as we will argue) the games that have a synchronized experience of theme through thematic elements are some of his most successful player experiences.

Game Designers’ Intended Game Experience as an Interpretive Category

Our content analysis reveals that theme is vital to Sackson’s game designs because it helps amplify his intended player experience, but before turning to our analysis of his rulebooks, it is important first to substantiate this somewhat speculative notion of “designer intent” within wider discussions of player experience in the board game community. Writing on BoardGameGeek, Oliver Kiley suggests that schools of game design might be productively distinguished on the basis of their “core priorities,” or central sensations that designers working within the school hope to elicit in players. The core priority for the “Ameritrash” school, for example, is “drama.” Games like Twilight Imperium and Talisman encourage players to experience exciting feelings of uncertainty, conflict, and tension by reliably featuring a host of key design elements: Rich narratives with often “epic” stakes, combative player interaction, considerable luck and/or chaos, and impressive “chrome” (i.e. materials or rules unique to the game title). In contrast, the core priority for the “Eurogame” design school is the sensation of “challenge.” Games like Catan or Puerto Rico motivate players to feel tested and accomplished through a different suite of common design elements: Innovative and/or intricate mechanics, indirect or constructive player interaction, fair and balanced forces, and tightly controlled decision spaces. Scott Erway poetically underscores the positive aspects of this priority in Loving Eurogames when he suggests that the design school essentially offers “refreshment for our souls. It is a refreshment that comes from having goals to seek and companions to join us in the quest in a world where sense rules over nonsense.” Outside of the purview of the larger schools, game designer Kevin Carmichael endorses a phenomenological approach to games when he encourages budding designers to pay special attention to the “core experiences” of any individual game prototype–the “emotions and feelings you want your game to provoke [in players] as determined by its mechanics and the way the theme is presented.” He argues that designers who approach projects with memorable experiences in mind tend to find more success in their final products than designers who rigidly adhere to a particular mechanic or theme.

Given the existing discussion of player experience as a central aspect of game development, we believe that it might be possible to find intended player experiences within the oeuvre of particular game designers similar to the core principles of the larger design schools, and (following Carmichael) that the chances of finding such a unifying experience increases alongside the success and profile of the designer. In some cases, the intended experience is relatively easy to locate. For instance, because so many of Stefan Feld’s game designs feature elements that grant players victory points for virtually any choices they make (a design philosophy succinctly captured in the semi-derogatory phrase “point salad”), we would venture that the intended experience for his players is the feeling of reward. Even if players do not ultimately win a game of Trajan or The Castles of Burgundy, they still reap the satisfaction of many guaranteed small “victories” along the way. In the case of other designers, the intended experience is more opaque. With hundreds of published titles to his name, Dr. Reiner Knizia would be difficult to categorize in this regard if not for his own comments on the matter:

For me, life is great because there is [sic] so many things to do, many more things than we can ever do. That’s what I expect from a game as well. I don’t want to sit there and say ‘there is nothing really to do,” or “what’s the least worst option” and wait a bit, this is boring! I expect from a game, that I sit there biting my fingernails, thinking I have so many things to do but I only have two actions on my turn. One game which really brings this to the foreground is Through the Desert, and that’s what I try to build into the game[:] this urgency of too many good things to do and not enough turns to do them.

Thus, a feeling of urgency is likely the intended player experience that unites Through the Desert with other Knizia classics like Tigris and Euphrates and Amun Re.

Sackson’s Intended Game Experience: Feeling Smart

In the case of Sid Sackson’s catalog of games from the 1960s, we believe that the intended player experience that unites them is a certain kind of cleverness that involves overcoming opponents through especially discerning play. It is a mindset that values subtlety over bravado and sneak attacks over outright assault. In a word, Sackson wants his players to feel smarter than the other players. Retrospectives of his work sometimes draw attention to this quality: “Sackson considered board games works of art, but he also clearly interpreted them as contests, tests of skill wherein a player or players win through smart play.”

Primary/historical documents featuring Sackson’s own words reveal this predilection as well. We know that Sackson concerned himself broadly with the effects of games on the emotional states of players. At points during the aforementioned 3M promotional tour, for example, he discusses the rise of “sick” games with violent and morbid themes in order to position his own titles as cerebral and wholesome alternatives. Elsewhere he elaborates on the particularly shrewd undertones of his more popular designs. While providing a play overview of Acquire in the March 1973 issue of Games & Puzzles magazine, Sackson notes that “it is surprising how often the crown will go to a player who has quietly and unsuspectingly brought his scheme to fruition while others, apparently in the lead, fought each other to exhaustion.” Resonant language appears alongside his designs in A Gamut of Games, a compendium of games that anyone can play at home with materials like paper, dice, and playing cards. After setting up the hand-drawn boards for “Paper Boxing,” for instance, “each player moves on this board, trying to outsmart the opponent.” The player left after all others have dropped out of “Take It Away”–the one forced to score remaining chips on the board negatively against his/her score–is officially designated the “patsy.” Similarly, publishing in Games magazine in August 1997, Sackson encourages players to yell “gotcha” when scoring over other players in the pen-and-paper game of the same name. Perhaps this underlying sensibility of outfoxing other players is the reason that Sackson, in an undated interview with Stephen Glenn, highlights intelligence as one of the major benefits that draw people to games in the first place: “Your body feels good after you exercise, similarly your brain feels good after a mental workout. Also, it’s fun to show how smart you are.” For Sackson, it is not enough to merely feel intelligent while playing games. The real “fun” of a game comes from displaying one’s craftiness, ostensibly to opponents that one has just defeated. It is no wonder, then, that he endeavored to amplify this quality in his own designs throughout his career.

Theme as a Vehicle for Clever Play in Sackson’s Games

Accepting the demonstration of cleverness as the intended player experience common to Sackson’s games elevates the presence of theme in these games beyond conventional understandings of theme as incidental rule aids. Instead, the thematic goals and elements of Sackson’s games in the 1960s are central and important to the creation of a “gotcha” mindset in players. Sackson’s “beloved brainchild” Acquire provides an illustrative example. The broad theme of the game is “business,” and the very first sentence of the rulebook communicates the thematic goal to players: “The main object of ACQUIRE is to become the wealthiest player by the end of the game.” Smaller thematic elements scattered throughout the rules develop the business theme and help players imagine the process of wealth acquisition. Tiles placed on the board in sequence represent “hotel chains” that can merge through careful placement, cards represent “stock certificates” that players can purchase and sell or trade for profit, and players themselves assume the roles of “chainmakers,” “founders,” and “majority holders” at different points in the game. Many people might intuitively associate running a successful hotel empire with a keen and even ruthless personality, but for those who resist making the connection, Sackson weds the thematic elements of the game to this posture quite explicitly. One major means of amassing the most wealth is by “shrewdly buying the right stock at the right time.” The game ends when a player announces that hotel chains can no longer merge according to the rules or one chain has grown to at least 41 tiles, but “a player does not have to announce that the game is over if it is to his advantage to continue playing.” In this way, the thematic goal and elements of the game are not merely ways of explaining to players where to place tiles or how to collect cards. They are invitations from Sackson to behave in a more crafty manner than one might otherwise entertain.

Understanding that Sackson intends to provide a stage for players to show off their smarts in his games helps to clarify the selection of theme in Sackson’s other designs from the 1960s. Business is only one arena in which people demonstrate guile, and while money, manufacturing, and trade represent significant thematic elements in Sackson titles from the time like Executive Decision, Venture, and Bazaar, there are also designs that explore practical intelligence in alternative contexts. One example is Sleuth. The overarching theme of this game is the world of crime detection and jewelry heists, and the thematic goal is to be the first player “to discover the identity of the missing gem.” This goal manifests through various thematic elements in the game itself: Some cards signify gems with varying qualities, while others allow players–in their role as detectives–to interrogate each other and gain clues about which gem card has been removed from play before the start of the game. Famous literary detectives like Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot are already renowned for their keen observation skills and their ability to outsmart even the most formidable foes, but Sackson again goes out of his way in the ruleset to connect the theme of his game to the idea of acuity. A player should gather information “through skillful questioning of his opponents,” after which he might use “his powers of deduction and logic” to win the game. In a section on strategy Sackson implies that only the most thoughtful and observant players have a chance of pulling off such a win: “As he gains expertise, each player will develop his own methods of recording evidence and other pertinent data on his Information Sheet…A piece of information which is useless at the time it is received may become crucial in combination with later evidence.”

Another example from Sackson’s games of the 1960s that invokes the experience of celebrating intellectual maneuvers outside the realm of business is the two-player Patton. Unsurprisingly, the theme of this game is war, with players participating “in three of the famous general’s most important campaigns.” One player commands the American forces led by General Patton, while the other controls the German Axis army. The thematic goal differs depending on which of the three game modes the players elect to play, but all three modes involve outmaneuvering the opponent on the battlefields of Normandy, Luxembourg, or Sicily. The ruleset includes detailed explanations of how to move troop pieces around the board with cards, as well as how to resolve conflicts and calculate “casualties” with dice. It is the two pages of “historical commentary,” however, where Sackson celebrates Patton’s crafty mind. As part of the invasion of Sicily, Patton struck unexpectedly and “took Palermo, receiving permission to do so after he had captured the town!” He emerged from the campaign “as an excellent tactician and an aggressive commander.” The included discussions of Normandy and The Bulge feature similar examples of Patton pinning and trapping the German military through clever and unanticipated deployment. We contend, then, that the themes of detection and war are not just “pasted on” to Sackson’s designs to help players remember the rules of Sleuth and Patton. Given his own management of these themes in the rulebooks, it is clear to us that Sackson employed these particular themes because they encourage the tactical behavior he saw at the core of his designs.

A final example from the time period helps solidify the importance of theme to Sackson’s designs through counter illustration. High Spirits with Calvin and the Colonel has players collecting two types of cards from a grid: High cards, which are worth positive or negative amounts of money at the end of each round, and Spirit cards, which allow players to trade or steal High cards from one another. Restrictions prevent players from merely selecting any card they wish. Sackson originally called the game “High Spirits” and designed it for adult audiences, but as it was his first game accepted for professional publication, the deal he struck with Milton Bradley required that the game feature characters from the cartoon Calvin and the Colonel in order to market the game to children. Sackson later confessed regret at this editorial decision, claiming that the company “ruined” the chances for the game’s success by tying it to an unrelated knock off of Amos and Andy. A cursory glance at the published ruleset inspires sympathy for Sackson’s position. The thematic goal here is identical to Acquire and the other business games of the era (“Be the player with the most money at the end of the game.”), but there is no clear sense of how this goal immediately resonates with the hijinx of an animated fox and bear. In fact, in place of the language of smartness present in the other Sackson rulebooks, High Spirits stresses a sense of low stakes merriment between the players: “‘HIGH SPIRITS’ is an easy-to-play card game which is full of surprises and hilarity!…SPIRIT cards tell the players what to do, sometimes for good, sometimes for bad, but always for high-spirited fun and enjoyment.” A critical study of the design suggests that a sharp sense of discernment and a knack for timing are far more important than a taste for revelry when it comes to playing the game well, but no discussion of shrewd or clever moves in the rules encourages players to adopt this posture. Consulting Sackson’s business diaries reveals that he tried to get High Spirits republished with Milton Bradley in its undiluted form all the way up until 1981. Given his later output that presents a much more synthesized connection between game theme and mechanics under the sign of clever behavior, it is perhaps not surprising that Sackson attempted to bring High Spirits in line with the rest of his oeuvre.

A Case Study on Focus/Domination

A case study that is of significant interest to our argument is the re-publication–and indeed re-theming–of Sackson’s notable game Focus, first published by Whitman games in 1965 (and also printed in Gamut of Games). The game was republished in an English edition in 1982 by Milton Bradley under the title Domination, although European editions kept the title Focus.

In the popular discourse around hobby board games, most people do not think of abstract games like this one as having a theme at all. However, Parlett addresses the relation of Focus to Lasca and other draughts-variant games (like Checkers) as various simulations of traditional military strategy. He argues that the aim of Lasca is “to gain total control by immobilizing all enemy pieces. Captured pieces are not removed from the board but are held (and moved) in custody, and may regain their freedom.” Focus draws on similar rules to Lasca. It does not use “soldiers and officers” pieces, but it does use control and capture in the player movement. There is also a similar type of capture and regaining of freedom for enemy pieces.

Because in draughts-variant games the thematic element of capture is common (as is the oppositional nature of the play), the re-theming of Focus to Domination is especially interesting in terms of the marketing of the new version, which moved away from the “All-American” wholesome image Sackson sought to cultivate in the 60s and 70s alongside 3M to a theme more strongly in line with the war concepts that are naturally present in the game’s historic derivation. This shift is best demonstrated by the TV commercial made by Milton Bradley for the game, complete with a military man yelling “Dominate! Dominate!” in the background. Perhaps this clear shift of the game from a freely available checkers variant to an obvious commercial theme reflected the professionalization of Sackson’s game career, as well as the continuing taste of the American public for strategic maneuvering games like Battleship that could reflect back to them the ongoing tensions of the Cold War, the great symbolic victories of the “Miracle on Ice,” and so on. Equally, reading Sackson’s March 1981 business diaries reveals how much of the name change to Domination from Focus was driven by his own desire for the game to be personally and financially successful. Because Focus had already been agented in Europe and Sackson was in dispute with one of his agents, it made sense to create a new title, rulebook, and components for the US Milton Bradley imprint so that there could be a new contract excluding this individual. Indeed, Sackson was so committed to the title Domination that even though there was an existing Alan Newman game with the title, he and Milton Bradley went ahead with it anyway.

Comparing the rules for the 1965 Whitman Focus set and the 1982 Milton Bradley Domination set, we see that Sackson emphasizes much of the skill and smart play he thinks makes a game enjoyable, and the two rulesets are largely in agreement on this point. In a section signed by “The Author” in the Whitman set, Sackson writes, “Focus is not Chess, or Checkers, or a cross between them. Focus is much easier to learn than Chess. All the rules can be learned in five minutes. Mastery of the strategy can take a lifetime. But who would want it otherwise?”. He follows this provocation with “Focus is, in the completely biased view of the author, a lot more fun to play than any board game of skill than has preceded it.” We see in this section Sackson’s emphasis that Focus is a game that draws on the historic lineage of classic board games, but the emphasis is on skill and fun. Domination’s own rules echo this introductory text with phrases such as “Easy as Checkers and as challenging as Chess” and “5 minutes to learn…mastery of its strategy can take a lifetime.”

In the body of the rules, we see other commonalities that establish that these rules are the same game with the same lineage and authorship. These overlaps include the ordering of the player instructions and explanations for movement, the explanation for a two vs four-player game, and the classic “strategy tips” that are common to so many Sackson games. In terms of exact wording used, we see that the players are still referred to as “opponents” and pieces are still termed as “captured” or “reserves” in the same way that Lasca pieces are.

The most obvious change in terms of re-theming is the title, which as “Focus” makes little sense other than a general strategy hint for playing the game. In addition to the name change, Domination makes only three changes to the wording of Focus’s rules, but these changes make a large difference to the experience of reading the rules and understanding the historical precedent of this game. First, instead of player piles (now “stacks” due to a component change) being controlled by the player who “tops the pile” (Focus), in Domination a player who controls the pile is said to “Dominate” the stack. This change extends the theme from the title into the player actions, linking the thematic element of capturing opponents’ pieces via the goal of control to the overall theme of the game–militaristic domination.

We can also see this thematic shift clearly in the second and third changes that were made between the editions of the game. In Focus we have: “Winning the Game: When it is a player’s turn to move and he controls no piles and has no remaining reserves, the game is over and his opponent is the winner.” In Domination we have: “Object: Dominate the game so your opponent cannot make a move.” Not only does the win condition become the “object” of the game, but its position was moved from the end of the ruleset to the header. The placement change clarifies the rules considerably. Before players see the rules for stacking and movement, they understand the thematic intention and goal–that they are to control and dominate their opponent. Secondly, this reframing makes sense from a point of view of player intentionality. In Focus the win condition is framed as forcing a surrender from the other player (i.e. if your opponent loses, you win). This creates confusion about the thematic goal of the game (“control”), as it is essentially framed in the negative. If the thematic goal of a game is supposed to provide a link between thematic elements such as capture (present in both rulesets) and the core theme, this confusion is likely to create a lack of cohesion in the thematic register of the game. However, in the Domination version with its upfront placement, there is an active framing of the win condition from the perspective of the winner which clarifies these thematic links.

To summarize, then, the main theme of Focus/Domination is better captured in its secondary title: dominating the most territory on the board through clever maneuvers. In this way, the game echoes the familiar, maximalist, American themes present in most of Sackson’s work (“most” points, “most” territory, and very often “most” money). However, realizing that theme often plays a role in inspiring Sackson’s intended experience for his players in other games from the same time period actually helps clarify the historical shift from Focus to Domination under Milton Bradley. The changes implemented in the Domination ruleset aligned the thematic goal, elements, and mechanics of play in a way that was lacking or at least obscured in the prior incarnation. In doing so, Sackson elevated the design to stand squarely alongside his other thematically consistent games.

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

Contrary to popular conceptions of theme being entirely absent, meaningless, or at best secondary in Sackson’s output from 1960 to the 1980s, we have endeavored to show here that his selected themes are actually critical aspects of his game designs because they encourage players to adopt clever behavior and mindsets–Sackson’s personal reasoning for playing games at all. The rulebooks for Acquire, Sleuth, and Patton exemplify this trend, and decisions surrounding the historical adaptations of High Spirits with Calvin and the Colonel and Domination reveal further reason to believe it. We believe that this understanding of Sackson’s work helps clarify puzzles about the man himself, as well as the role of theme more broadly in contemporary board games.

Sackson’s games often speak to an aspiration to have and keep it all. Some might venture that the thematic goal of many of these games–the attainment of great success as a business tycoon–is ultimately a sales tactic, or at the very least a gloss that speaks unmistakably to the hardworking and skillful business acumen valued in America during the heyday of his design career. While these perspectives probably have some measure of truth, we must also remember that Sackson came from a modest background and had a relatively lonely childhood. In his lifetime he only ever rose to limited financial success (he lived in the same house in the Bronx most of his married life). In light of the present analysis, we suggest that this thematic constancy was perhaps in part a way for Sackson to inspire a sense of personal connection with those who played and enjoyed his designs. It seems from his biography that the close bonding of family and friends was closer to Sackson’s vision of what constituted success than the impersonal big business of Wall Street, despite the choice of game themes he chose to temporarily inhabit with his gaming groups. We contend that Sackson’s desire to inspire his players to be clever speaks to this uniquely personal vision of accomplishment–a desire to share his personal gaming philosophy and the joy of “feeling smart.” The Sackson sensibility for writing rules and sharing variations and playing tips invites all sizes of groups to share this vision with him, even posthumously, and in so doing his legacy has contributed to shaping the culture of hobby board gaming on an international level.

As such, there may be some temptation to characterize Sackson’s economic themes centering on intellectual acuity and a “gotcha” feeling as a certain type of ideological “safety,” especially within recent debates regarding historical and cultural themes in eurogames. Though steering clear of overtly racist material would seem to be a low bar for modern designers, a cursory glance of contemporary eurogames reveals that this is not so. Designers’ proclivity for historic romanticism and erasure of real places and events in favor of idealized versions has produced a bounteous share of thematically problematic games. We believe, however, that Sackson’s choice and management of theme may introduce equally problematic distortions on matters of race, class, and gender. Schwartz suggests that the major theme of Sackson’s work is a relentless fantasy of capitalism–undoubtedly a fantasy because everyone begins with an equal chance of success or failure. Capitalism in real life is not ever as equal as Sackson’s rulesets suggest; it is subject to privileges of race and gender that can never be balanced with simply starting a new game. One could argue that the business games we have considered here erase these distinctions in a way that rewrites social realities and encodes a white, male view of the world where fairness is not fantasy, but a new reality. In interrogating Sackson’s contributions to the lineage of eurogaming, then, it is clear that one cannot divorce theme from the game, no matter how abstract. While we might look to Sackson’s careful management of theme as a model for contemporary designers in some ways, we must also acknowledge that thematic goals like “most money” are not necessarily value-neutral and can create an illusion that, when people interact, inequities are an inevitable and even desirable result. Indeed, one might even suggest that inviting gamers to demonstrate their “cleverness” is not a moral good. Instead of encouraging sophistication, it unnecessarily ranks players in a way that mirrors social inequities at the expense of social connection.

—

Featured Image is Acquire. Taken by authors.

—

Abby Loebenberg is an Honors Faculty Fellow and Principal Lecturer at Barrett, the Honors College at Arizona State University. She holds an PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology and an MPhil in Material Anthropology and Museum Ethnography from the University of Oxford. She received her B.Arch from the University of Cape Town. As a scholar her area of study is the study of play and games and she has published in peer reviewed journals, contributed chapters to books and contributed to conferences. As a teacher integrating an interdisciplinary approach to the study of material and visual cultures particularly, play games and design are her special topics of interest.

Robert L. Mack is an Honors Faculty Fellow and Senior Lecturer at Barrett, the Honors College at Arizona State University. He holds a PhD in Communication Studies from The University of Texas at Austin, an M.A. in Communication Studies from Colorado State University, and a B.A. in Speech Communication from Northern Arizona University. His research and teaching focus on rhetorical form in popular culture and psychoanalytic media criticism. He is also the co-author of Critical Media Studies: An Introduction, 3rded. (Wiley-Blackwell).