Settlers of Catan is a German board game by Klaus Teuber, first published in 1995. The game pits players against one another in an economic civilization-building race as they build structures and gather resources on the hexagonal tiles that compose the game’s board. The game has achieved critical acclaim (winning the Spiel des Jahres in the year of its release) and popular success, especially in the U.S.: a 2010 Washington Post piece called it “the game of our time.” Board Game Geek, a popular international board-game hobbyist website, ranks Settlers of Catan 168th out of 79,923 games (as of 8 October, 2015) on its “hotlist.” This paper situates Settlers of Catan in its context as a popular game in the U.S., and proposes a subversive gameplay modification that addresses that context.

It was during a game of Settlers of Catan that I began to wonder why, or even if, Catan was uninhabited. I played on, though not without pushing down even more pointed questions about the narrative that I, as a settler of Catan, was enacting. Whose wheat was I harvesting when I rolled a six? Whose land was I altering when I built my roads and settlements? And with what entity was I trading when I shipped two wood in exchange for one resource of my choice at the port?

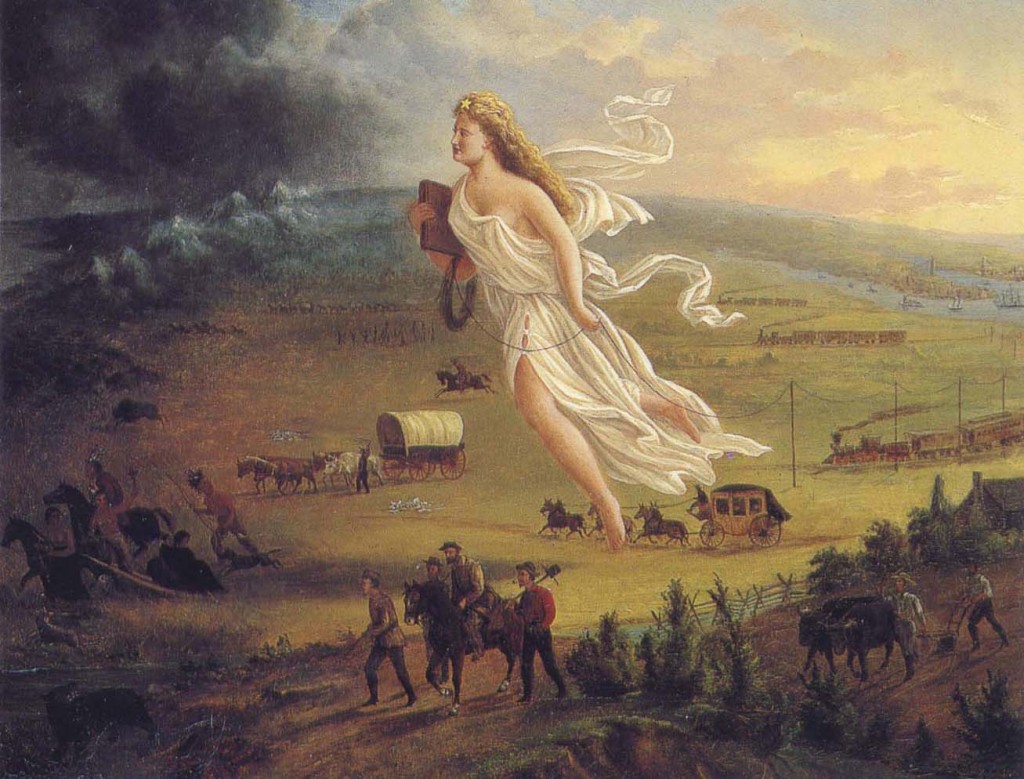

It became clear, at least to me, a white person playing this game in the U.S. in the early 2010s, that every game of Settlers of Catan re-tells the American myth of White European settlers stumbling upon a fertile land that was theirs by right, encountering no meaningful resistance, and acting on behalf of God and Country to develop economies, settlements, and cities in this “New World.” My first thought was to never play Settlers of Catan again. But this response seemed inadequate: while it might solve the problem for me, it would not equip anyone else to wrestle with these troubling issues, and would put me in some awkward positions whenever Settlers of Catan came up as a possible game to play. So I decided to come up with a new game, based on Settlers of Catan, but one that would bring to light the things that had so troubled me about the game.

Settlers of Catan, both by its title and its thematic elements, situates itself as a game about settling new land. While the game does not root itself in any historical reality, playing it in the U.S. creates a link to the real historical settlement and concurrent genocide of indigenous peoples. Consider the “frontier myth,” a phrase that describes the work of Frederick Turner Jackson, whose 1893 essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” attributes the rapid development of the U.S. in the late 19th century, and the specificity of the U.S. American character, to mystical forces contained in the “empty” and thus edenic American West. Settlers of Catan, by allowing its settlers to find the island of Catan in a similarly edenic state, reifies this myth, which helped to render American Indians invisible. Thus, Settlers of Catan, when played in the U.S., is complicit in continuing to make indigenous communities invisible. Primarily in order to counter this troubling aspect of Settlers of Catan, and to create a game that I feel comfortable playing, I have designed a variant of Settlers of Catan titled First Nations of Catan.

First Nations of Catan: Introduction and Summary

In First Nations of Catan, one player (of the possible four that a standard Settlers of Catan set allows) plays as the First Nations, the indigenous inhabitants of Catan. These semi-nomadic people have the same goals as the Settlers (earn 10 victory points by building settlements, cities, and buying development cards), though they accomplish them in different ways.

Rather than playing on the edges and corner of the game’s hexagonal tiles, as the Settlers do, the First Nations inhabit the center of each tile, signaling their centrality to and initial presence on the island. This creates visual contrast with the Settlers, who cannot penetrate the interior of any hex tile, but instead are limited to building their roads along the edges of the tiles and their settlements at intersections of roads. The island of Catan is open to its indigenous people occupying its hinterlands, but forces the invading Settlers into the liminal spaces. This parallels the historical realities of the (White) settlement of North America in relation to indigenous North Americans: European settlers moved inward from the coasts, and later, along major rivers, while indigenous peoples as a whole occupied the interior in addition to the coastal lands.

While this rule creates an attractive metaphor, it limits the First Nations player’s opportunities: In Settlers of Catan, players may gather a resource from any one of the three hexes that their settlement abuts. By forcing the First Nations player into the center, First Nations of Catan significantly reduces their resource-gathering capabilities. This metaphor runs contrary to the realities of North American settlement: indigenous peoples were successfully planting, harvesting, and hunting on the land while European settlers were struggling to adapt to unfamiliar plants, soils, and weather conditions. Nonetheless, I wanted to create a game where the visual representation of the First Nations differed from that of the Settlers on the playing space, and having the First Nations play in the center of the tiles accomplishes this.

To restore balance of resource opportunities to the game, I have given the First Nations player another playing piece: The Tribe. This marker can move across the board, gathering resources as it goes. The Settler players have no such game piece at their disposal. The Tribe piece also allows the First Nations player to take military action against the Settler players, who may only defend themselves, and may not initiate military action. This is the most radical change that I have made to Settlers of Catan. In “Orientalism and Abstraction in Eurogames,” William Robinson suggests that, by focusing on economic development, Eurogames abstract and erase military conflict from the histories they represent, particularly military conflict against non-Europeans. By bringing military conflict from the realm of the abstract back into the realm of the explicit, First Nations of Catan undoes the disappearing act that Settlers of Catan performed on Catan’s indigenous peoples.

I realize that introducing a combat mechanic is troubling in its own right; games too often revert to simulated violent conflict as a thematic element. In my experience, many players enjoy Settlers of Catan precisely because it does not have a combat mechanic. However, this reading of Settlers of Catan ignores the presence and function of Knights and the Largest Army tile.Just because the violence on Catan is not simulated by die rolling does not mean that it is not present in the game’s thematic materials. The empty, edenic state of the “frontier myth” is complicated and, to a certain extent, undone, as soon as violence occurs on the frontier. By creating a chance for more-explicit simulated violence to occur, I hope to have created a Catan that cannot be perceived as either empty or edenic.

Designer’s Diary

In this section, I will describe my process of designing First Nations of Catan. By leaving a trail, I hope that other designers will be encouraged to craft similar subversive games, and that new games will arise to fill the gaps that First Nations of Catan has left open.

The act of re-purposing a game’s pieces to create a new narrative counter to the original game’s narrative is not a new one. In “Strategies for Publishing Transformative Board Games,” William Emigh suggests and catalogues numerous instances of this practice. The ability of the player to usurp the role of the game-maker was, for me, perhaps the most exciting aspect of making First Nations of Catan, and the one that points to other ways for players of Eurogames to address some of these games’ failings. Having finished (as much as any game is every finished) First Nations of Catan, I can say that the game seeks to address the invisibility of indigenous peoples in the original Settlers of Catan, and to bring more explicit conflict to the economic-conflict-only ethos of Eurogames in general and Settlers of Catan in particular. Earlier drafts of this game addressed these issues in certain ways, but either did not address them fully enough, or raised too many other issues in the process. Additionally, I was looking to create a game that used the same pieces contained in a standard Settlers of Catan set, allowing anyone who can play that game to also play this new, revised version.

The game’s initial form did away with Settlers altogether, allowing players to play as various indigenous Catan-ians attempting to cooperate or compete with each other to develop society on Catan. While this solved the invisibility issue by foregrounding the existence of indigenous peoples on Catan, it quickly became apparent that this game was merely Settlers of Catan by another name, as the 2-4 factions looked and played almost identically to the Settlers in the original game.

The necessity to make explicit the abstract nature of military conflict in Eurogames was the solution I settled upon for the next iteration of the game. The historical narrative of the (European) settlers creating economic prosperity for their own competing factions by, as a group, disenfranchising the indigenous (American Indian) people needed to become more explicit in the gameplay. Needing both First Nations players and Settlers on the board quickly led me to the idea of asymmetrical gameplay: all the players are playing the same game, but may have different victory conditions, or have different ways of achieving the same victory condition. In short, the First Nations player needed different rules from the other players.

This iteration of First Nations of Catan centered on conflict. The First Nations would attempt to drive off the settlers while the Settlers attempted to eradicate the First Nations. As soon as I began this iteration, it became clear that it was more troubling than Settlers of Catan. Every player was aggressively enacting violence on another racial group, and had no other viable way to win. I hesitated here. Troubling games have their place, and can be very effective in reminding privileged White U.S. Americans (men in particular) of their own complicity in historical horrors. Consider Brenda Romero’s 2009 game Train, in which players must load a train with passengers. Only later do they learn that this train is headed to a Nazi concentration camp. Making such a game out of Settlers of Catan would, no doubt, be useful in a U.S. context, reminding those of us descended from European settlers that our wealth is derived from ill-gotten plunder and genocide. My project, however, was to create a Catan game that I would feel comfortable playing, and this troubling variant was not it.

I had, however, landed on a useful mechanic, and one that helped differentiate my nascent game from Settlers of Catan: hidden movement. Hidden movement games allow a player or players to indicate their position(s) not on the board itself, but in another way that keeps the position(s) of their pieces a secret, often by using pen and paper and a location-based notation system. In this too-conflict-driven version of First Nations of Catan, the First Nations player controlled the nomadic First Nations group as it roamed across Catan. The location of this group was noted by creating a map of the playing area on a piece of paper and marking the location of the group as a turn-based number inside the hex where it was currently (unbeknownst to the Settlers) located.

This hidden movement idea moved the game into its third iteration. The First Nations still had a secretly-moving group associated with them, but now their goal was not militaristic. Instead, all players were competing for points via the standard economic competition model of Settlers of Catan. The First Nations gained the ability to build settlements and cities, and gather resources as they developed their society alongside the encroaching settlers. A military option was available (the hidden piece could strike at Settlers, removing their constructions from the board) though it was not the only path to victory. This version of the game came close enough to accomplishing my goals, and was balanced enough when played, that I published it on my blog, along with a short rumination that became the core of this piece.

This version, however, had two flaws—one practical, one ideological: By requiring players to use a pen and paper, and to draw a new map of Catan for every game, I had made the game harder to use, and thus less likely to be played. Additionally, if the invisibility of indigenous peoples was the concern I was hoping to address, using hidden movement seemed antithetical to my purpose, as it erases pieces from the play area.

By removing the hidden movement mechanic from the game (the Tribe piece replaces it) and retaining the other elements from the game’s third iteration, I had a game that worked both practically and ideologically. It required only one extra piece to be added to the basic Settlers of Catan game, and it played well. This is the game I settled on, and whose rules are included here.

First Nations of Catan: A Success?

Designing this game required balancing three directives: Create a game that was fun to play, that did not erase indigenous people from its narrative, and that did not deviate from the pieces contained in the basic Settlers of Catan game.

The first element is perhaps the easiest to confirm, as it was my primary concern when beginning this design. First Nations of Catan creates a narrative for Catan wherein indigenous peoples exist, interact with settlers, and have a fair chance of surviving the encounter by winning the game.

Based on limited playtesting, I believe I have accomplished the second goal as well. First Nations of Catan is a balanced, asymmetrical strategy game, in which classic Eurogame elements (economic competition, long-term planning) mesh with so-called “Ameritrash” combat simulation mechanics (dice-based combat, strategic positioning of military units). Each player has a fair chance at winning the game.

The final element was not, in fact, successfully met, but it was a compromise I was willing to make. By requiring an extra playing piece, I have added a small barrier to entry. I was hoping that players of First Nations of Catan would be able to simply download and print the rules, open their Settlers of Catan box, and play the game. But the Tribe piece requires one extra step: finding a piece from outside of the original game that will fit on the game board and be recognizable to all players. However, this is only a small hurdle, particularly for players who own any other board games, as almost any piece will suffice. Additionally, requiring the First Nations player to bring something onto the game board undoes, in a small way, the erasure of indigenous narratives that Settlers of Catan enacts.

First Nations of Catan accomplishes the goals I set for it, but there are many other possibilities for the island of Catan. Perhaps the troublingly violent variant that I had landed on could be expanded upon to create an uncomfortable reminder of European genocide of American Indians. Perhaps a cooperative game could be created to allow for a utopian Catan where Settlers and First Nations learn to co-exist peacefully.

In making this game, I set out to deal with my own discomfort at seeing problematic and inaccurate history recreated in a fictional realm. This type of re-writing is commonplace in reaction to non-game fictional texts. Fanfic and fan movies, for example, are well-established genres as reactions to movies, novels, television, and even video games. First Nations of Catan made me realize the possibility of game remixing as a sort of analog-game-based fan fiction. By using (mostly) the materials provided by the original text and remixing them, First Nations of Catan allowed me, as a player of Settlers of Catan, to address that which I find problematic about the original game without rejecting its system outright.

I am hopeful that players of Settlers of Catan will play First Nations of Catan and think about the differences between the games’ narratives, especially European-descended people playing in the U.S. However, the possibilities of game remixing more generally are most exciting to me, and I hope that by contributing to this stream, First Nations of Catan inspires other game-players to become game-makers and re-makers.

–

Featured image by Valentin Gorbunov CC BY.

–

Greg Loring-Albright makes tabletop and real-world immersive games as Plain Sight Game Co. (http://www.plainsightgameco.

–

Appendix: Rules for First Nations of Catan

When the Settlers arrive on Catan, they quickly encounter the First Nations of Catan, a semi-nomadic people who begin competing with them for the resources that, until the Settlers’ arrival, had been their undisputed right…

Continue reading The First Nations of Catan: Practices in Critical Modification