Mermaids of Iedo, our serious historical board game, was designed with five experiential goals in mind: cultural preservation, environmental awareness, slowness, nostalgia and historiography. In this article we expand on how these goals were selected and incorporated these ideas into the mechanics of the game.

Serious games are designed for an educational or empathetic objective—they encourage players not only to enjoy the play, but also to engage more deeply with the content of the game. Many serious games have been accompanied by other informal learning scaffolds, such as exhibits or curriculum, and have been used as a representational record of cultural heritage and practice. As designers we are creating the experiential parameters for our players, and by extension, framing their interaction with a cultural practice. As serious game designers who have endeavored to tell a historical story, we identified several key cultural elements that framed our work. In the process of designing Mermaids of Iedo, we came across certain limitations of board games as a medium, namely how abstraction and player attitude can upset and obscure the educational motivations woven into gameplay.

Like many others before us, we are excited by the potential of serious game design. For example, Stewart Woods has examined the design implications available from serious analog games. More broadly, James Gee examined in 2003 how games provide an informal learning space for players. Greg Loring-Albright detailed the process of modifying (modding) the existing game Settlers of Catan (1995), to account for the indigenous populations that were being colonized and exploited by the base game’s Western Imperialist mechanics. For Loring-Albright, the development of non-Western mechanics and culture within the game space was important to decolonizing the game’s logic. Contributing another alternative to imperialism and conquest, LaPensée describes the development of her game, The Gift of Food (2016). For LaPensée, “culturally responsive board games can function as important pathways for passing on Indigenous ways of knowing.” Likewise, we echo Trammell and Waldron’s call to explore mechanics that “are not fundamentally linked to mass-market commercial industries.” By selecting the haenyeo we aim to tell a story that lies outside of the mainstream fold of interaction.

Mermaids of Iedo was built as an analog game in order to capture positive player interactions and a sense of community. The game’s initial incarnation was envisioned as a digital mobile game that would be played within the few minutes of a subway commute in Seoul. Players could pick up a game or two and engage with a brief experience of meditative slowness. We hoped that the game could build on these interstitial moments and appeal to the sense of oneness and deliberate action found among free divers, whose activities were far away from the bustling bballi bballi rush of urban living. Mobile games are a big cultural influence in South Korea and throughout the world; furthermore, the mobile platform provided what we initially believed to be an intriguing setting for a game about slowness. However, while the technological aspects of a mobile game provided certain advantages, they proved ultimately insufficient in capturing the more intimate, community-minded actions that we were hoping to embody. The platform of an analog board game allotted a better paradigm of player interaction and allowed for greater interaction with the core material. Ironically, the choice to utilize a tech-lite approach in the form of an analog game offered more opportunities for player engagement, personal reflection, and communicability of the game material.

As American researchers, one White and one Chinese-American, we hope that documenting the decisions we made when creating a board game based on South Korean culture allows us the critical space to interrogate the etic perspective we bring to this work. One of the key concerns in our development of the game was how abstraction blurs the original source material–what gets lost in the process of making a functional and mechanically sound game? We acknowledge that representation from an etic perspective can quickly fall victim to stereotypes and tropes found throughout the media which exoticize Asia. By documenting our process and positionality, we allow our decisions an important transparency that acknowledges the active position our work takes in the construction of cultural knowledge.

The Haenyeo of Jeju Island

Over the past 100 years, South Korea has undergone an immense shift from agrarian pre-modernity to the heights of technological integration. This sense of “compressed modernity” has had unforeseen circumstances upon South Korean society. In fact, the decline of traditional cultures like the haenyeo of Jeju island may be directly correlated to South Korea’s embrace of the global economy. The haenyeo, which roughly translates to “ocean women” or “mermaid”, are groups of community-organized diving women on the South Korean island of Jeju dating back to the early Joseon dynasty (1392-1910). While originally a co-ed practice, fishing by diving has only been done by women since the 17th century. These fisherwomen would spend an average of 4-6 hours each day in the water during the warmer months, with fewer hours in the winter months. In addition to the physical labor of swimming, haenyeo responsibilities included farming, selling their catches, and maintaining their fishing equipment. As South Korea’s economy advanced, participation in diving decreased from 14,143 in 1970 to 5,659 in 2002. The demographics of the fishing community also shifted. In 1970 4.6% of divers were over 60 years old, while in 2002 52.5% of divers were 60 or older. This decline has been counterbalanced by the push towards modern labor practices and urbanization, which has further depleted the work pool.

As South Korea advanced into its position as a center of technological development, it began to eschew and jettison activities that had once been commonplace. Recognizing the need to preserve its cultural practices for future generations, the South Korean government created an advisory board designed to identify and secure not only tangible historical artifacts, but also the intangible practices, performances, and craftwork of South Korean history. Lee and Myong refer to the haenyeo as “emancipatory pioneers” due to their struggle and popular resistance movement during Japanese colonization from 1910-1945. We feel that it important to tell the important and ephemeral story of the haenyeo fishing practices for these reasons.

Rules

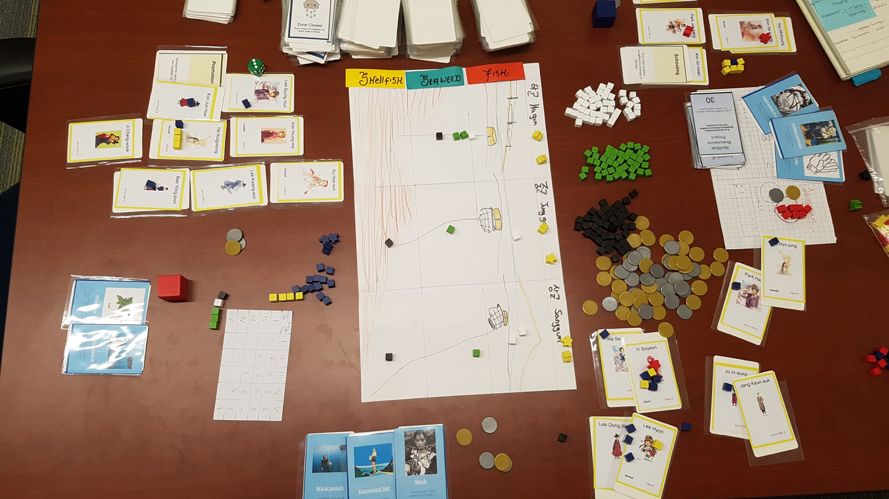

Mermaids of Iedo is a card game where players play as families of haenyeo . The collective goal of the game is to survive through the entire twentieth century. Players tell the story of a community moving from the Japanese colonization period (1910-1945) to the present era where being a haenyeo is no longer the most economically viable path. Mechanically, the game ends either when players reach Era V, the 2000s, when community happiness reaches zero, or if any player is eliminated because all their family members are dead or unable to be played. Following setup, gameplay is broken into five eras of non-uniform rounds and time lengths. Each era starts with a major historical event that affects all families and replenishing the resources on the sea board. The core game loop is a round, consisting of a sea phase and a shore phase.

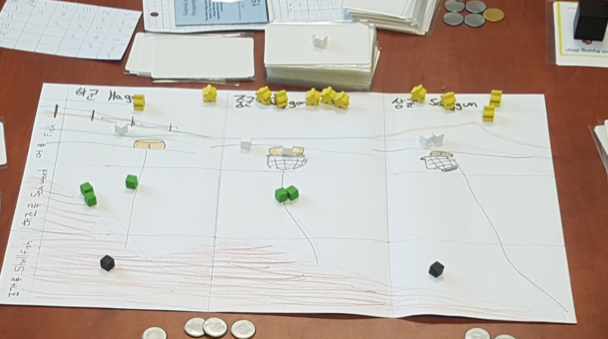

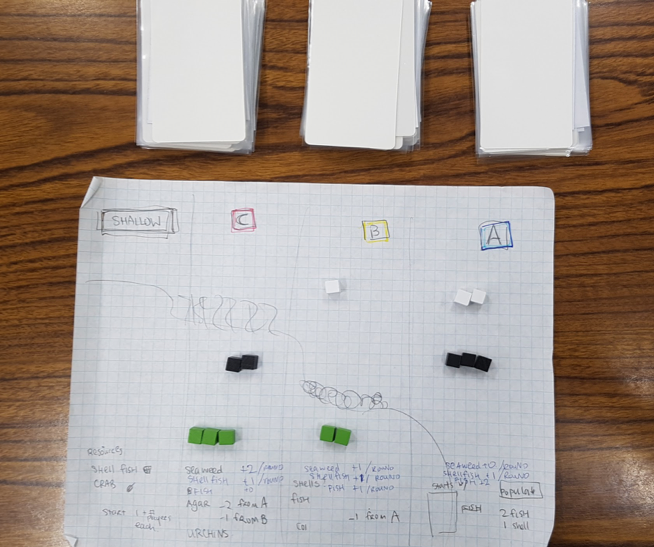

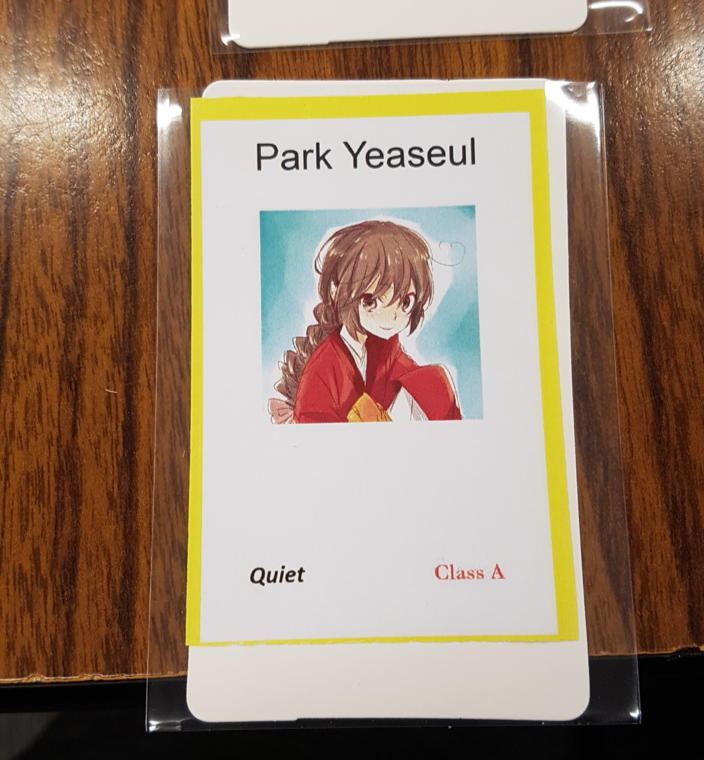

During the sea phase, each player chooses a haenyeo within their family to go out into the water to fish. Silently, players draw cards within their designated fishing zone (C, B, A, from closest to shore to furthest at sea). Zone assignments in haenyeo practice were assigned based solely on breath capacity, with minimal prejudice between groups; in the game, zone assignments are marked on the character card for all women. These cards indicate the product (seaweed, shellfish or fish) that was discovered as well as its worth (e.g. 1- 5). Within the deck are also special events that might happen during this zone (e.g. a tool breaks, a current washes away part of the catch) affecting the day’s catch. When all players are finished fishing, they share the day’s catch with the table. This sharing process was included to resemble how the haenyeo would gather for dinner and discuss the long day’s work. As players go through their actions, they take a resource from the sea board and collect the listed currency. If there are no more resources of the corresponding type, then the action is explained as the haenyeo searched for this resource but did not find any.

During the shore phase, all non-haenyeo family members collect their salary and families pay their cost of living. One player draws a timeline card— an event that happens to the entire community: for example, there might be a community event or government action that creates opportunities to find work elsewhere. When this event is resolved, each family can take certain family actions, such as marrying, having children, purchasing items or sending a character to the city for education or work. The decisions made during the shore phase are meant to drive the narrative– mechanical consequences of decisions are not obscured, but the narrative realities may be revealed later. At the end of the shore phase (the end of the round), players can choose to pool resources to host a festival. The game then continues to the next sea phase, or, after a set number of festivals are held, an end-of-era event happens and the game continued to a new era.

Analysis

In looking up information about the haenyeo from documentaries and papers, we recognized themes in the portrayal and motivations of the haenyeo. From these, we identified five goals for the experience of the game that we wanted to create: cultural preservation, environmental awareness, engagement of slowness, nostalgia of experience, and historical context. In each of the following subsections, we detail why each goal was selected and how each goal was incorporated. We discuss the games which influenced these designs and reflect on how effective the design of each theme was in initial play-testing.

Cultural Preservation

We began looking into the haenyeo with the understanding that we were portraying a fragile cultural practice. The diving women of Jeju have been classified by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage since 2016. While the invocation of Intangible Culture status by UNESCO does not justify its inherent importance, the current trajectory of the practice and its presumed extinction within the next 50 years highlights the temporality of the haenyeo. As designers, we wanted to explore a dated practice. Having players come to terms with the fragility of cultural practice was one of our design goals.

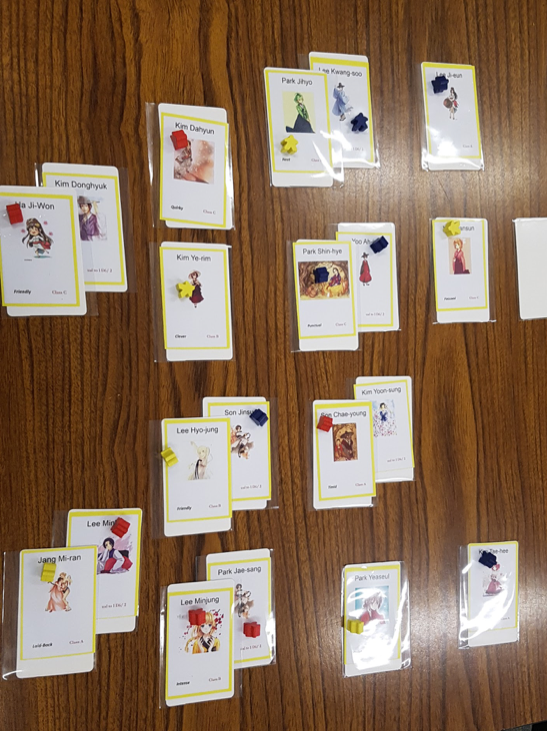

To capture this, players begin play by selecting a female haenyeo diver. Actions during the shore phase represent the decisions that were available to these women: for example, players choose to get married, have children, send their children to the city for education, or pursue alternative work to diving. These decisions mimic the same life experiences that the haenyeo and their families would have faced. As economic and historical events inform the cards read during the game’s shore phase, players are able to make a better living by sending their characters away from the village to find work and education in the city instead of in the sea. At the end of the game, the historical reality of the haenyeo’s cultural practice is recognized: there will soon be no more haenyeo. This is captured visually as tokens representing the number of haenyeo are removed from the sea as characters pass away or choose not to continue their practice.

The creation of the game was created in part to build cultural awareness of the haenyeo and the history surrounding their way of life, even as it dies. However, many haenyeo wanted better lives for their children, and better opportunities: we wanted to echo this sentiment in the arc of the game. As we thought about how to represent a fragile practice, we were inspired by Capital (2016), a game in which players build boroughs within the city of Warsaw. Capital rewarded the construction of neighborhoods and adjacent community centers in ways that inspire different boroughs which prioritize different configurations. The game also simulates World Wars I and II by making the players remove specific tiles. We looked to Capital as an example for capturing not only events in the historical context, but also as a way of preserving the perceived values of the haenyeo as they encountered these events.

The goal of cultural preservation formed the provided the narrative backbone and aesthetic of our game. The eras within our game were inspired by the eras in Capital. Just as each era in Capital adds new neighborhood configurations or special structures, each era in The Mermaids of Iedo presents a new narrative event for the families and introduces or balances new economic pressures. One of the drawbacks of our design goal is that a player has to play the entire game to experience the entire arc that addresses cultural preservation. While the visual aesthetics contribute to the preservation of the haenyeo’s equipment and tools, the ultimate “dying practice” narrative is only communicated via experiencing the entire game arc. This makes it difficult to incorporate within a shorter play experience or to capture within a class period. We anticipate creating curriculum scaffolds so that the play experience can be properly divided and supported in a formal or informal learning environment.

Environmental Awareness

Monitoring and maintaining sustainable resource gathering practices was an inherent part of the haenyeo’s responsibilities. There is growing concern for maintaining a balanced global environment and climate; this concern is compounded for practitioners who rely on the environment for their livelihoods. Environmental degradation due to global industry is a core component of our everyday lives. This real-world tension between environment and personal need is reflected in the game because player-controlled families are, particularly early in the game, very dependent on the sea for their survival. Watching the resources available in the sea and maintaining that balance is thus pivotal for players. Serious games can help position players to build awareness of the human impact on the environment. By having players carefully consider the available resources on the sea board, we hope to encourage player awareness in the real world.

The primary action of the fishing phase involves drawing actions from their haenyeo’s zone-designated fishing deck. While most cards reflect resources that can be exchanged for currency, others reflect the dangers of working at sea. Each zone has associated risks: for example, in the shallows of zone C, tools might break. Further out in zones B and A, the very movement of the ocean’s currents can become dangerous. Such dangers pose a relatively rare but very real risk to the haenyeo, who face injury or death if they are not vigilant. While not the narrative focus of our game, we wanted to record and reference some of the risks of these divers working at sea.

Engagement with Slowness

The haenyeo’s time inside the water was characterized by engagement and attentiveness. Every breath represented an awareness that the sea was as much their source of income and space of meditation as it was a dangerous force of nature. The work necessitated their being fully immersed–literally and mentally– in the water. Gathering time was limited by the duration they could hold their breath, as haenyeo practices generally eschewed the use of technology outside of wetsuits, goggles and simple tools. Rather than rushing their gathering or hunting, the haenyeo encouraged slow, intentional movement. Compared to thebballi bballi business of everyday modern life, the sea demanded a meditative slowness to work. As designers, we wanted to capture this slowness for players because it seems absent in everyday life. The concept of slowness and methodical action is one that is found in many games, but we were particularly influenced by Tokaido (2012), a game about traversing the historical Tokaido road in Japan. In Tokaido’s gameplay, players meander from station to station along the path from Kyoto to Edo (modern day Tokyo); instead of racing to finish the journey as swiftly as possible, players are encouraged to leisurely explore the road and sights along the way. The meandering pace motivates players to explore, tarry, and dawdle, mimicking real life travelers of the era. This emphasis on a sedentary pace was influential in crafting an experience that was driven not by speed, but by oneness between player and environment.

Slowness is demonstrated during the sea phase, where players are required to be silent during the duration of the phase. To recreate the sense of slowness, we emphasized silence as period of reflexivity and deliberation. Compelling players to be quiet was influenced by The Quiet Year (2013) and Consentacle (2018)–games which limit how players can communicate. The silence which mimics the lack of communication while out in the sea, provides time and space for players to act reflexively and deliberately. During the sea phase, players simultaneously “farm” the sea by collecting fish, shellfish, and seaweed cards and adding them to their nets. Even though the fishing happens simultaneously, players must share the ocean and be mindful of other players. A change in weather conditions drawn by one card can affect all players in a designated zone. Divers are expected to harvest enough ocean resources to sustain their family needs and save for the future. There is no time limit, as players are encouraged to thoughtfully interact with the ocean as opposed to scramble to hoard resources. As sea resource cards are collected in-phase, events may occur that prohibit further play or alter the experience in important ways: for instance, a card that introduces a storm or shark can force divers out of a fishing zone, limiting access to the resources. While players are balancing their actions with those of other divers, we ask players to slow down and engage directly with the consequences their choices—hasty action can spell disaster for the game’s ecosystem.

Nostalgia

Nostalgia was the hardest design goal for us to evoke within the game. We hope that the game evokes a sense of nostalgia by encouraging players to discuss the plentiful conditions of the early game. Players take on the role of a haenyeo family and “live” through the 20th century, making decisions about their family’s future. The different eras serve as a framework for players to view the history of the divers. Linda Hutcheon, in reflecting on the tension of power and irony in nostalgia, describes the irreplicable feeling of longing and an emotional response to “deprivation, loss, and mourning.” Nostalgia for something that our players have never experienced, in our case, would resemble the bittersweet feelings of a family divided across generations and a sense of serene tragedy. Although the sea is a space of work, the haenyeo’s profession extends far inland. In preparing the catch and making food for the family, there is an inter-generational connection deeply rooted in being a haenyeo. While some haenyeo continued their work out a simple love for the sea, others emphasized the practical rewards of their work. For example, fishing was simply a practical way to provide a better future for their children. We tried to recreate inter-generational tensions by highlighting how diving was both a means to economic advancement, yet also a path of planned obsolescence.

The story of the haenyeo and South Korean history is not a happy one. In South Korea, this sense of impending tragedy has been characterized by the conception of han, the thorough and deep awareness of sadness. Perhaps the board game version of This War of Mine(2017) best captures the emotion of tragic serenity we aimed to evoke. Players familiar with the video game of This War of Mine (2014) expect a journey of hard ethical decisions that always inevitably ends in doom. When we played the board game, having this narrative expectation instilled a kind of serenity and acceptance. We as players knew, even when we were making the best available decisions, that we were headed for defeat. Mermaids of Iedo seeks to address a similar sentiment: the precarious nature of cultural practices.

quiet are flavor text designed to inspire deeper roleplaying of the characters. Image used with permission by the authors.

We really wanted the game to evoke a sense of fracture with how it presented the generational divide. In developing the family tree layout, we looked to Crusader Kings II (2012) as an exemplar. In Crusader Kings II players take on the role of dynastic families rising and falling in the ranks of European empires in the Middle Ages. Players balance the immediate concerns of their character against the larger health of the family across centuries of time. While for much of the game, the player makes choices based on what they want for their current character, the play objective necessarily shifts at some point to making decisions that will establish an effective dynasty for the player’s family. At some point, the unrelenting progression of time requires that the current character make sacrifices in service of their enduring legacy. In Mermaids of Iedo, player choices during shore phase affect their lives and their family members’ lives.

Nostalgia is a difficult emotion to capture. Although we attempted to capture it by evoking a sense of generational character development in our game, the game’s larger goal of telling the story of the haenyeo may ultimately draw an audience that is unfamiliar and therefore not nostalgic about the story told.

History and Context

Finally, and arguably most important to the design of the game, was the sense of family and history as a fundamental part of the haenyeo’s experience. The social effects of the history of Jeju impacted all citizens. While the time inside the water was a period of meditative slowness and uniformity of experience for the haenyeo practitioners, their lives ashore included the everyday struggles of child rearing, family dynamics, and community political gossip. Haenyeo were not only colleagues in the water, but a community of women who talked while farming or preparing food ashore.

Captured primarily through the event cards in each shore phase, the historical context has been integrated as a primary storytelling and framing aspect of the game. We envisioned this in a two phase time-spatialization, where activities on shore furthered the timeline. The constancy of the sea phase creates a uniformity of experience for the haenyeo practitioners, and drives events and opportunities resolved in the shore phase. Meanwhile, the daily happenings of shore phase influence which characters participated in the sea phase. Both everyday life events and larger historical movements had to be captured within these storytelling mechanics–balancing these elements has been an ongoing struggle.

In the process of creating a history of the haenyeo, we were heavily influenced by how Crusader Kings II and Freedom: The Underground Railroad (2012) represent different historical periods. In Crusader Kings II, the duality of current individual needs and longer term family needs helped us develop how players in Mermaids of Iedo must also balance the present and the future of their families and community. Freedom, set during the Abolitionist movement of the American Antebellum era, inspired us to deviate from the calendar’s typical decade interval and to design around uneven periods instead. In escaping the uniformity of time, the game was able to focus on the events that created family and cultural bonds, as evidenced by those living through the Japanese Colonial period, the Korean War, or the Korean Democracy movement. For players this means that events are placed in the context of family members who lived through these times as opposed to living between marks on a calendar. Our goal in telling this histroy was to capture the emotions behind influential events in haenyeo history and situate this within larger events affecting the South Korean nation and peninsula as a whole.

Conclusion

Mermaids of Iedo is a game still in development. In this essay we have focused discussing how we approached the design of intangible things like, environmentalism, temporality, nostalgia, and history in the the mechanics of the game. Mermaids of Iedo attempts to capture a cultural experience. While the game does not depict the experience of every family living on Jeju, or perhaps even the experience of a single one, it does capture a facsimile of the experience of being a haenyeo family in the 1900s. And while the qualitative experience of designing and iterating through versions of the game cannot be fully and concisely transmitted, the process of designing emotional experiences in games by documenting the intentions, inspirations and decisions of this particular game design experience can. We hope that our work allows others interested in serious games to glean some of what we have learned about the game the design process.

As researchers, our goal was to explore the process of developing a serious game and how designer choices create emotional experiences as well as educational outcomes. As designers, our goal was to create a game that celebrated the haenyeo of Jeju Island while drawing attention to the fragility of their practices. As we worked through incorporating our selected themes, we discovered that various aspects of design, such as periods of silence, can emphasize emotional connections. Attempting to capture the essence of this cultural practice required a much broader interaction with the history and community that the haenyeo lived in. While we could have made a game that focused on the mechanics of the diving women, that game would have been bereft of the emotional richness behind the practice. Meanwhile, characteristics that we presumed at first to be important could be reasonably abstracted–details such as how seasons influenced the resources of the sea faded in comparison to the unfolding of how larger historical events impacted the family. We hope our serious game is hopefully able to represent historical narratives and provide an awareness of how the precarity of the environment affected the livelihood of families. Other thematic goals, such as a meditative slowness and a nostalgic affect, were unfortunately more difficult to implement.

–

Featured image by Chosun Bimbo 2 @Flickr CC BY.

–

This essay was written by William Dunkel and Minerva Wu.

William Dunkel is a PhD student in the Department of Informatics at the University of California, Irvine. He is interested in how games can be designed to further informal learning, globalization and play, as well as media ventriloquism. His past work has looked at sonic representation in Overwatch, temporal constructions of play, and the state of the Korean game industry. William earned his MA in Korean Studies from Korea University, and is currently revisiting the Warring States period of Japan by playing Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice.

Minerva Wu is an Informatics doctoral student at the University of California, Irvine interested in what happens to players cognitively during gameplay, and how design elements make games fun and conducive to learning. Current projects investigate student learning of academic and social-emotional content in games and game communities.