Editor’s Note: Analog Game Studies solicited this piece from its author with regard to design decisions in Storium, and is in no way officially associated with or receiving any remuneration from the Storium creators. We think it is an interesting design study as an analog-digital hybrid, and we hope you think so too. -Evan Torner

—

Storium is an analog game for collaborative storytelling adapted to an online, asynchronous mode of play. Writers compose Storium Worlds filled with genre-appropriate tropes and types, which are then used by Narrators to generate conflict-laden scenarios for a group of players. Players advance the story by playing Storium World-determined cards and writing fictional prose to illustrate these cards’ effects. The completed Storium reads like a short story with a strong focus on the characters.

Since my early playtesting for the service, I have engaged with Storium both as player and Narrator, and I have also joined many other creators as a Storium World writer during this summer’s Kickstarter campaign. To date, it is one of the most fascinating game spaces with which I have interacted. Though Storium is situated online, it has inherited much directly from tabletop design and quite literally a part of the”story games” design school.

Inherited Design Principles

Storium is played asynchronously and lacks the verbal/facial expressions of players, which one normally reads for cues in a tabletop or larp setting. Despite this, Storium shares much with the design and implementation of tabletop RPGs and larp.

As you play through a Storium, you select new goals for your character, create new Strength and Weakness cards signifying her/his capabilities, and take other actions that have significant effects on your character’s narrative arc. The number of Strength/Weakness cards you can play never increases, and you never become mechanically superior to your fellow players. The card hands a player has are much smaller than, say, the kind of skills spread you’d see in D&D, or a World of Darkness game, which limits the number of mechanical moves a player can make in a given round. This structure is reminiscent of D. Vincent Baker’s tabletop RPG Apocalypse World and those games that share its creative DNA, denoted by the label “Powered by the Apocalypse.”

This sort of game manipulates the ways that characters interact with each other and the game world by specifically defining their potential moves. Tight budgeting of players’ mechanical influence on the narrative pushes players to carefully consider their moves, as well as to think creatively about how to use their small pool of resources (in this case, their cards) to best achieve their narrative goals. The collaborative scene framing and the shared narrative control in Storium evokes games like Jason Morningstar’s Fiasco, and the brevity and scarcity of mechanical tools in player’s hands is reminiscent of Will Hindmarch’s Always/Never/Now.

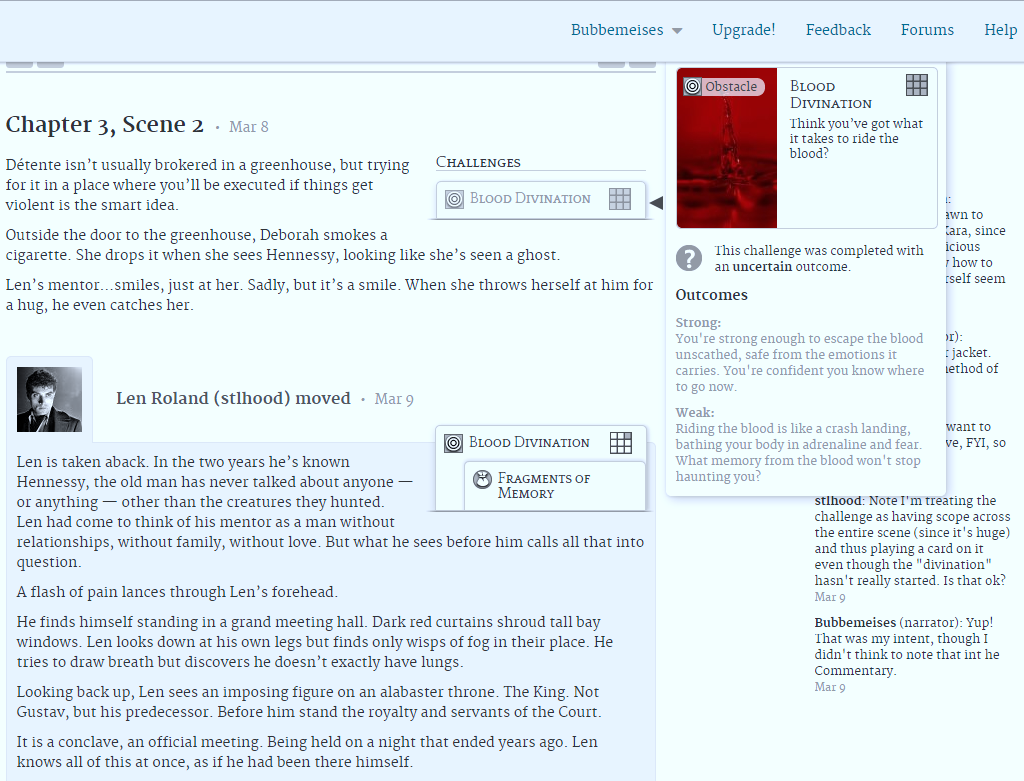

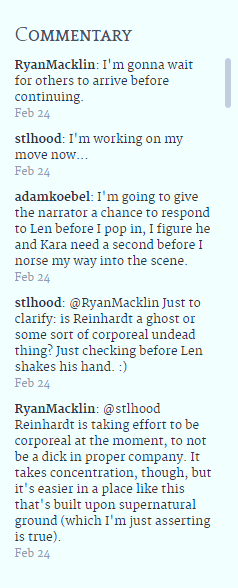

Card limits keep the narrative moving without letting any one player take over the narrative and shove fellow players out of the scene. In every scene, a player can only play a maximum of 3 cards. Players are free to add more descriptive text to the scene, but cannot influence the narrative’s outcome once their cards have run out. In the game’s Commentary sidebar, players note how many and what kind of cards they have left at the start of a scene. Though not every Storium sees the level of narrative authority distributed to the point where one might ask “Hey, can I fail this challenge because it really fits my character to do that?” players are often exceedingly generous about sharing narrative authority. In the Storiums where there is a fairly open (often unspoken) agreement among players to share that narrative authority, the out-of-game discussion often keeps the game itself moving smoothly through the scenes and Storiums themselves.

Characters confront adversity and challenges in most tabletop games, be they ones thought of as mainstream, such as D&D, Shadowrun, Pathfinder, or story games such as Monsterhearts or Lady Blackbird. Storium also focuses on adversity, and encounters are quite explicit about what threat they pose. A Storium is propelled forward via Challenge cards.

Challenge cards drive conflicts, form mysteries, and can help create dramatic stakes from nothing. Tasks players can try to perform include swaying an NPC to your side, getting out of a heist gone wrong without killing anyone, or conducting surveillance to catch a monster. But challenge cards are also easy to write and frame poorly. When a player gets through a Challenge with a “Strong” or “Weak” Outcome, they choose to write exactly how that win or loss looks. The Narrator only deals with uncertain outcomes. Cards with extremely specific outcomes give players very little room inside the narrative to exercise their agency and narrative authority. Open-ended questions help, and offering success-at-a-cost can intrigue players. Some Storiums live and die on the strength of the Challenges their Narrators write. This is fascinating to observe with regard to Storium‘s analog heritage, because it mirrors how different GM styles around a table or at a larp can cause a group to embrace or walk away from a game.

Storium players have a genuine choice about whether their characters succeed or fail to a greater degree than some players realize. I do see some Storiums where players “hoard” the positive cards that give them the greatest possibility to control the narrative to their characters’ advantage. As players get more acclimated to Storium, however, they tend to choose failure more often. Like tabletop games, Storium depends heavily on GM facilitation skills, savvy use of its system, and buy-in from players and Narrator alike into Storium‘s foundation of collaboration.

Whose Turn Is It?

For players in a tabletop or live-action role-playing game, one determines turn order by a mix of in-character proximity to an event (narrative determination), and the skills listed on the character sheet ( mechanical determination). With Storium, there is neither formalized nor mechanical enforcement for determining turn order. Instead, the game offers tools to help people keep taking turns. Every Storium offers its players the same feature: the “poke.” It sends an automated message to the person being poked, telling them who poked them and reminding them to log in soon so they don’t hold up the story. As an engine that drives asynchronous cooperative fiction, Storium has little use for a mechanically-enforced turn-taking system.

Through the poke function, a thematic solution exists to keep players engaged and moving the story along. We can remind each other to take a turn, finish turns, and make sure the fiction being written does not grind to a halt. Storium needs only enforce that the turns are taken, not who takes them. Such communication can also be achieved by using the Commentary built into each Storium to leave messages everyone in the Storium can see to remind people to take turns.

Since Storium is an environment that allows for asynchronous play, participants of a given Storium can stay in touch, regardless of geographic and scheduling differences.

The Narrative of Failure

Storium‘s design encourages collaborative storytelling, which means it must establish a social and emotional environment that lets the players productively negotiate which character should do what. These negotiations are surprisingly mechanics-centric, as opposed to indie games, where negotiations tend to be about story decisions. Is Myka the better choice to talk someone into letting them into a building because they know her from school? Is Vanessa the best choice to feel out someone for the coven because she’s the most charismatic of the witches? These are negotiations about guiding the narrative.

I was introduced to indie RPGs through principles such as “fail forward” and “playing to lose” to make failure interesting. Yet it is still rare, in my experience, to see players “sign up” for failures. In Storium, I have watched players negotiate who would provide the “best failure” in a scene. These negotiations deal with failures as beats that would guide narrative forward, allow players to empty their hand and reshape their character cards, bring about introspection for characters, or cause opportunities to bond or fall apart to the characters as a group. They negotiate through the “Commentary” function of the Storium website, which is running down the side of the screen.

People playing Storiums often become deeply committed to the narrative, without any jockeying to be martyr or hero in a scene. This emotional state comes from Storium‘s design: narrative authority is genuinely shared, so a player’s decision to have a character fail in the scene is imbued with psychic weight. Players usually agree upon a failure that would be motivated by something beyond pure mechanics, a failure that would pack the most short or long term narrative weight. Horror as a genre works by imperiling its protagonists; Storium does the same. Meta-level discussions draw out more than just players’ emotional commitments, but also their very collective notion of how a satisfying story is told.

Mechanical concerns (such as scarcity of cards) and short or long-term emotional pay-off become weighted through these meta-level negotiations about failure. If a demon worshipping bad boy fails a girl he grew up with, that might be the keystone to a redemption narrative. Each failure has the potential to rewrite a character and their future, and meta-level discussions let players process their emotional investment in their characters to determine the “appropriate” failure for the moment. Players retain ultimate narrative authority over their character in any case. As far as mechanical incentives go, being the one to say what failure looks like has its own appeal. In addition, participating in Challenges also means the players plays cards from their hand, which reinforces their connection to the story world as they narrate.

Intellectual Property, Fanbases, and Storium Worlds

Storium is unlike fanfic and play-by-post communities in a number of ways, with its relationship to intellectual property (IP) as a core point of difference. Fan-based communities often use well-known IP, like Harry Potter or Star Wars, whereas Storium uses its own IP to avoid copyright infringement. Storium makes efforts to attract fan communities while avoiding legal issues, as seen in their successful Kickstarter. More than 30 authors contributed Story Worlds to Storium, drawing an audience wanting to play worlds written by their favorite creators.

Storiums are created by an active fanbase, and writers willing to adapt their existing works onto a different platform may choose to clear the rights and do so. Storium is not held back by the absence of widely known IPs such as the Marvel superheroes or Star Wars, but rather enabled by fans and writers being on equal footing. Fans get to follow the work of their own favorite creators on the site, and creators get the support of world building tools for their writing.

When Storium becomes more widely available, it will give digital gamers and storytellers access to many mechanics and techniques currently used by the analog role-playing game community, and analog role-players will finally have an online role-playing system playable with people from around the world that requires a very similar skill-set to that required by the type of role-playing they already do.

–

Featured Image “Some Stories Can’t Be Told in Words,” by Michael Shaheen CC BY-NC-ND.

–

Lillian Cohen-Moore is an award-winning editor, and devotes her writing to fiction, journalism and game design. Influenced by the work of Jewish authors and horror movies, she draws on bubbe meises (grandmother’s tales) and horror classics for inspiration. She is a member of the Society of Professional Journalists and the Online News Association.